By LT Jason Lancaster, USN

“It is no exaggeration to say that without the Texas Navy there probably would have been no Lone Star State, and possibly, the state of Texas would still be a part of Mexico.”

– Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

Texan Independence and the First Texas Navy

Despite their integral part in the creation, defense, and maintenance of the Republic of Texas, today, the Texas Navy is a footnote in modern history. Mexican invasions that never happened and gunboat diplomacy criticized so heavily by President Houston destroyed the reputation of the Navy and erased their history from public memory.

In 1835, Texas’ population was small, rural, and dispersed across a vast territorial expanse. There was no industrial base to speak of; Texas imported everything by sea. Galveston Island, on the upper coast, was the most important city and port in Texas, followed by Velasco on the Brazos River, and Indianola on Matagorda Bay. Texas exported timber and cotton but imported everything else. To lose the ports would mean the destruction of the republic and the death knell of the Anglo-Texan dream.

With the start of the Texas Revolution, Texans formed a provisional government and declared independence on March 2nd, 1836. Despite a provisional government primarily composed of farmers, ranchers, frontiersmen, and lawyers, some of the government’s first acts issued Letters of Marques to ship owners and laid the foundations for a navy. Officials debated how generous to make the terms for privateers, but viewed privateering as a temporary measure to protect the lifeline to New Orleans and fight the Mexican Navy while the provisional government created a regular navy.

With privateers guarding the coast, the hunt for ships began and eventually four ships were found. The flagship of the new navy was the 18-gun brig Independence, a former U.S. Revenue Cutter. The other ships were the Invincible, an eight-gun Baltimore slave ship, the Brutus, a 10-gun schooner, and the six-gun schooner Liberty, a former Texas privateer.1 The squadron quickly cleared the Gulf of Mexican ships. Following the major Texan defeats at the Alamo and Goliad, the navy shielded the Texan coast from invasion and prevented the Mexicans from using the Texan coast for resupply, forcing Mexican logistics to come overland from Matamoros and Laredo instead of landing supplies and men at Copano Bay in southern Texas.

The Texas Navy of the revolution was short lived. Texas won independence at the battle of San Jacinto. The Texas army captured Mexican President, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana and forced him to recognize Texas’ independence and withdrawal Mexican soldiers from Texas at the Treaty of Velasco. Despite the treaty, the two nations continued to spar at sea. In 1837, a numerically superior Mexican fleet attacked the Texas ships near Galveston Bay. The Mexican fleet captured the Independence, while the Brutus ran aground on a sandbar in Galveston Harbor and broke up in a storm. The Texas Navy was gone. Under President Sam Houston, there was no drive to procure replacements. Without a navy, the eight ships of the Mexican Navy were free to harass commerce and cut Texas off from New Orleans commerce. Fortunately for Texas, a diplomatic row between France and Mexico over the treatment of French citizens’ pastry shops resulted in France sending a large fleet to protect its interests. The French captured the Mexican navy and demolished the fortress at Vera Cruz. The Mexican naval threat had been eliminated… at least temporarily.

Republic of Texas Politics

From the beginning of Anglo settlement in Texas, there had been a faction desiring annexation into the United States. Annexation was a highly popular idea in revolutionary and republican Texas. However, there was a second party that believed Texas should be independent. This faction believed that Texas could be the greatest power on the North American continent, and should expand to the Pacific Ocean. American immigrants such as Mirabeau Lamar carried Manifest Destiny to Texas and dreamt that Texas could rival the United States in power.

In Texas, presidents could not serve consecutive terms, so after President Houston’s first term expired December 1, 1838, Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar became president of the Republic of Texas. President Lamar’s vision for Texas was as expansive and glorious as his name would suggest. He believed in Texas’ own manifest destiny. Lamar’s policies as president reflected his belief in the republic. He sent military and trade expeditions to conquer Santa Fe and gain control of the overland trade routes to California, rebuilt the navy, and created alliances with rebelling Mexican provinces.

The Texas Navy was reborn. New warships were constructed in Baltimore, Maryland. Instead of enterprising merchant sailors, Texas searched for talented young American naval officers bored by slow promotion and the dull existence of the peacetime navy. Texas found Lieutenant Edwin Ward Moore to command the squadron with the title of Commodore and the rank of Post Captain.

Former President and now Congressman Houston ridiculed these policies and accused Lamar of entangling Texas in foreign disputes irrelevant to the republic. Congressman Houston did not think Lamar should squander money on expansionist schemes, but save money and wait until the United States annexed Texas.

One of Lamar’s most controversial policies included interference with Mexican domestic politics. In the 1840s, Mexico possessed two major political philosophies: the Centralists, who favored a strong central government typically led by dictators such as General Santa Anna, and the Federalists, typically found in the extremities of Mexico on the Yucatan Peninsula and on the border with Texas. These states felt threatened by the strong central government. Their livelihoods were based primarily on commerce with foreign countries and any threat to international commerce threatened their livelihoods. The Centralists placed high tariffs on imported goods to support Mexican industrialization. The high tariffs affected the merchants in the Yucatan provinces and along the Rio Grande, who frequently rebelled against the Central Government. Both regions proclaimed themselves republics, the Republic of the Rio Grande centered on the now Texas city of Laredo, while the Republic of the Yucatan comprised the provinces of Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo. Both of the new republics asked for Texan support but only one republic was successful. President Lamar went on to conclude treaties of friendship with the Yucatecos. The Yucatecos offered to pay for the Texas Navy if it was employed on the Yucatan Coast. The only aid for the Republic of the Rio Grande was an unofficial army of filibusters formed in Texas, in support of the fledgling republic.

While serving as a Texas Congressman in between presidential terms Houston opposed almost everything that Lamar had done, and Houston’s political following constituted its own political party. Under his leadership, the congress disbanded the army and ignored issuing commissions for naval officers. For three years, the navy sailed without any official documents stating their legitimacy.2

President Lamar’s expansionist mindset was not without precedent. In the middle President Houston’s first term in July 1837, the Texas Navy under the command of Captain Thompson claimed the island of Cozumel, in the words of Captain Thompson, the “star spangled banner [referring to the Texas flag] was raised to a height of forty-five feet with acclamations both from inhabitants and our little patriotic band.”3 In addition to the island of Cozumel, the navy took possession of the Arcas Islands, a small island chain in the Gulf of Mexico. The Arcas islands proved a valuable halfway point between Galveston, the Yucatan, and Vera Cruz. Only 250 miles separated them from Vera Cruz, while it was 623 miles from Galveston to Vera Cruz, or 789 miles from New Orleans.4 The Texans used these uninhabited islands as a rendezvous, recreational area, and supply base. The central position of the Arcas Islands allowed the Texans an easier time of blockading ports and intercepting Mexico’s commerce.

The Texas Navy used this advanced position to interdict Mexican trade and the navy seized British and American merchantmen carrying weapons and military supplies to Mexico. Often times these countries ignored their own pasts and demanded compensation from the fledgling republic. Similarly to how during the Napoleonic Wars the Royal Navy captured neutral ships with cargos bound to France, the Texas Navy was defending Texas from similar Mexican aggression and could therefore intercept neutral ships. Several times the Texas Navy captured vessels like the U.S. brig Pocket bound to Mexico with weapons and gunpowder hidden in barrels of flour. Houston cited occurrences such as these as examples of Texas Navy lawlessness and a primary reason for the dissolution of the navy.

President Lamar sent expeditions to Santa Fe and other places claimed by Texas and Mexico. The Santa Fe expedition’s goal was to bring the city of Santa Fe under the jurisdiction of Texas. Santa Fe was a valuable trading center in the southwest. This expedition crossed several hundred miles of unexplored terrain to reach Santa Fe, but they lost all of their supplies, and were forced to surrender to the Mexican garrison of a village outside Santa Fe after encountering inhabitants resistant to the idea of becoming Texan. The prisoners were marched to Mexico City. The Santa Fe expedition, along with several others, taxed the resources of the republic. Arms, food, and accoutrements cost money and Texas could not raise the funds to pay for it because the government lacked the power of direct taxation. It was incredibly difficult to raise the means to make Manifest Destiny a reality. Instead of money, soldiers were paid in land bounties. The financial cost of empire proved to be the downfall of the Republic of Texas.

Recognition

The last act of President Jackson recognized Texas independence. However, this did not guarantee protection. On September 25, 1839, France became the first European power to recognize Texas signing a “Treaty of Amity, Navigation, and Commerce” with France. Trade did not guarantee protection. From 1836 until the annexation process began in 1844, Texans had to maintain their Independence by force. A navy is an expensive tool. But, when properly used, and properly supported, is well worth the investment. According to Captain A.T. Mahan, the “influence of the government should make itself felt, to build up for the nation a navy, which, if not capable of reaching distant countries, shall at least be able to keep clear the approaches to its own.”5 The close proximity of the Texas coast to the Mexican coast, combined with the relative poverty of both national governments, allowed two small naval forces to operate in the Gulf. Both navies combined never equaled more than fifteen men of war. Often times, they could never put more than two or three to sea at one time. The Texas Navy’s primary mission was to protect the independence of Texas, done through the blockading of the main Atlantic ports of Mexico.

The blockades strangled the commerce of Mexico, and forced British diplomatic recognition of Texas, followed quickly by Belgium and Holland. In 1840, the Mexicans were still recovering from the French assault in 1838. They had no navy to defend their shores from the Texans; however, they quickly and desperately searched for one. The Mexicans sought complete dominance over the western Gulf, and ordered two new steam ships of war. In addition to these, they found, armed, and commissioned several sailings ships.

Mexican shipbuilding projects frightened Galvestonians. The Texas Navy was ill-used by President Houston. His hesitancy to spend money on maintenance, pay, and supplies caused the ships’ material condition to deteriorate and the crews to go unpaid. Her officers received pay only three times in as many years.

Mexico postured threateningly toward conquest of the Yucatan and then Texas, causing hysteria in Texas, and the hysteria increased because the navy was stuck in New Orleans without money to recruit crews, pay its debts, or maintain the ships. The navy did not even need Texan taxes, just President Houston’s support for the Yucatecos, who had been subsidizing the fleet for two years. Commodore Moore had operated continuously on the Mexican coast, blockading enemy ports, extracting ransom money from them, and disrupting trade with Europe. Houston simply had to allow subsidies to continue, as well as make periodic expenditures toward the upkeep of the navy in dry dock and refitting.

President Houston’s Militia Navy

On the few occasions Houston desired the navy’s use, his orders for them were entirely improper for both the size and nature of the fleet vis-à-vis the opposing force. Houston’s experiences as a soldier led him to believe the best way to protect Galveston was to have the navy moored in port as a fleet-in-being. Following Houston’s orders meant the navy could be blockaded in Galveston by a superior force and rendered useless, similar to what had happened to the Brutus and the Invincible in the first navy during Houston’s last presidency.

There was a great debate on the measures necessary to protect the republic. President Houston had great experience with the use of militias on land, and believed that a naval militia would be an inexpensive and viable option for the fledgling republic. President Houston favored militias on land and sea to save money. However, a naval militia cannot accomplish the same objectives as a standing naval force commensurate with protecting Texas commerce. Sea control is the goal of a navy. The Texas Navy’s mission was to protect Texas’ international commerce, while disrupting the Mexican commerce by interdicting trade, and destroying or defeating the enemy’s fleet.

The use of militia ships proved to be complete and utter folly. The Englishman William Bollaert served as a volunteer “waister” aboard the steamer Lafitte, one of three militia ships operating out of Galveston. President Houston sent the militia squadron to interdict a rumored Mexican invasion fleet. The cruise was a complete fiasco, with the ships luckily failing in their mission to intercept the enemy force. The Lafitte did capture one small prize, but poor discipline and lack of naval training proved the ineffectiveness of a militia fleet. Mahan said that the best way for a fleet to protect a port was “drawing the enemy forces away from shores through offensive action on the high seas or forcing them to concentrate against a powerful if inferior force.”6 President Houston repeatedly defied common sense naval strategy; luckily, his defiance did not cost the life of the Republic.

President Houston and the Navy

President Houston’s handling of naval affairs is incredibly controversial. Why was President Houston so belligerent toward his own navy? There are perceived reasons for Houston’s antipathy. The first Secretary of the Navy, Robert Potter proposed dismissing Sam Houston from his post as commander-in-chief after the battle of San Jacinto. Secretary Potter had opposed his appointment to the post to begin with.7 In addition to these actions in the wake of San Jacinto, Houston’s great victory, Secretary Potter had ordered the first Texas navy on a cruise forbidden by Houston, and then joined the cruise himself. Perhaps a part of the answer is that Secretary Potter’s actions had caused Houston to associate the navy with his disgust for Secretary Potter. When Houston was a member of the Texas Senate, he led his large faction in opposition to all large financial projects, including the navy.

Painting, San Jacinto Museum of History)

In 1842, Houston sent three naval commissioners to New Orleans where the fleet had been stuck for lack of funds, to order the fleet to return to Galveston, and for Moore to relinquish command to the next senior officer. Moore, alerted by Yucateco friends of the eminent fall of Campeche, persuaded Commissioner Morgan to allow him to engage the Mexican fleet and attempt to relieve Campeche, lest the Mexicans invade Galveston next. Commissioner Morgan concurred, and they proceeded to Campeche. Houston was outraged. He declared Moore a pirate, and asked the “naval powers of Christendom” to “seize… and bring them into the port of Galveston.”8 Another example of Houston’s continued anti-Moore stance comes from a speech he made after annexation in the United States Senate where spoke, “that miserable Commodore Moore… who would fall by his own poison, or be strangled by his own venom… He, like a bloated maggot, can only live in his own corruption.”9 The Writings of Sam Houston, volume VI; contain a 32-page harangue of Moore’s actions as commodore. Houston successfully prevented Commodore Moore and the other Texas Naval Officers from receiving commissions in the United States Navy after Annexation. Houston won his feud, killing all memorials to the navy as well as pensions and land bounties to her sailors.

The Battle of Campeche

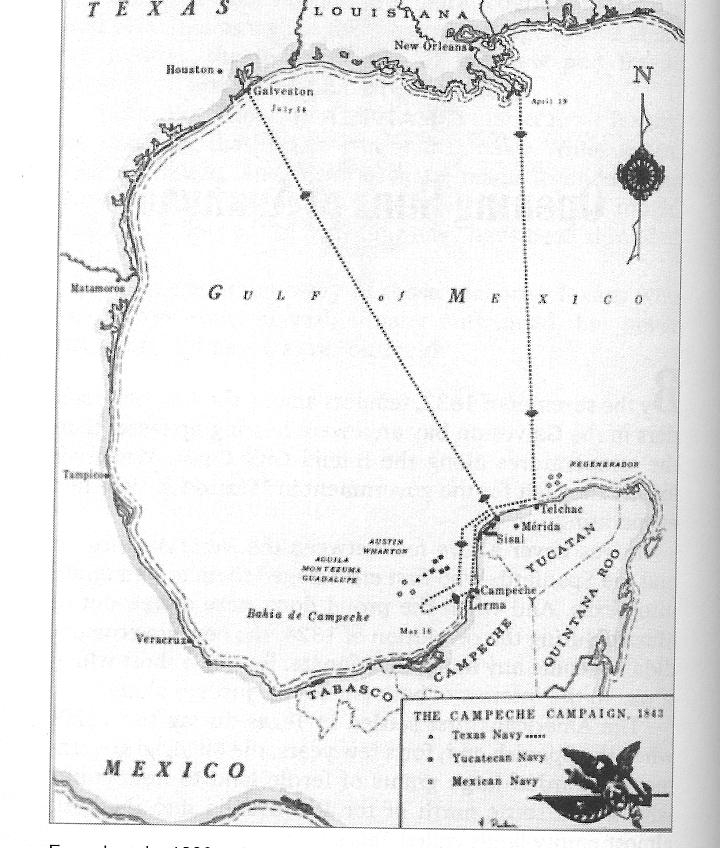

In 1843, before Moore was declared a pirate, he set sail to do battle with a greatly superior foe. The Mexican fleet consisted of two modern steam ships of war, officered and manned by Britons. In addition to these two steamers, the Mexicans kept four or five sailing ships blockading Campeche. Moore headed for Campeche with his two ships the Austin and the Wharton. After a long and brutal siege, the citizens of Campeche were preparing to capitulate, when in the distance they spied the Texan ships. They broke off negotiations with the Centralists, and cheered the approaching ships. The newly arrived Texans had a difficult task to accomplish. Outnumbered three to one, they sailed out of Campeche to meet the adversary. The Mexican ships refused to engage the Texans and continually withdrew in the face of the Texans, fighting a running battle with them.

Eventually, the Texans were compelled to break off their actions in defense of their allies in Campeche and return to Galveston, not by enemy action, but betrayal at home. President Houston had declared his own Navy to be pirates and outlaws. Commodore Moore received a copy of Houston’s piracy declaration in Campeche, and was forced to return to Galveston. Moore had no desire to risk his men and ships to the consequences of piracy charges if captured by the Mexicans. Despite President Houston’s declaration of the navy as pirates, Commodore Moore’s squadron returned as heroes, the sheriff refused to arrest him; balls were thrown in honor of him and his officers.

Annexation

There were unconfirmed reports that President Jackson had sent his young protégé Sam Houston to Texas to bring her into the Union. Houston denied these reports, and proof has never surfaced. However, he used every trick in the book to encourage the United States to annex the state. He engaged in talks with European powers Britain and France, frequently conversing with European attaches such as Captain Charles Elliot R.N., and the Frenchmen, Viscount Craymayel and Dubois de Saligny. Viscount Craymayel believed all of the peace talks with Mexico completely futile. Moreover, he asserted that the only way “for Texas to escape from her precarious position would be… annexation, which has always been the desire of the population.”10 Craymayel also accused the United States of using Texas to drain Mexican resources to prevent them becoming a rival on the continent.

With annexation efforts decided in Washington D.C., instead of in Texas, Houston attempted annexation through another tack. He spent time with the British Charge d’Affaires in Texas, Captain Elliot, RN. At times, he hinted at emancipation, although never ever specifically saying such a thing. When word of this arrived in America, the newspapers went berserk claiming Britain was trying to defeat them from “within” 11 Sam Houston’s coy discussions with Britain helped persuade the United States to annex Texas. Houston explained his often-confusing diplomatic initiatives thusly “just as a woman with two suitors might use coquetry to prompt the interest of the one she favored, you must excuse me for using the same means to annex Texas to Uncle Sam.”12 The people loved Sam Houston’s explanation for his actions; the people loved, and still love Sam Houston. When it came time to vote for or against annexation, the people voted overwhelmingly for annexation. In the election on October 13, 1845, there were 4,254 votes for annexation with 267 votes against annexation.

Conclusion

Today we often remember the heroes who fell at the Alamo, the men who were massacred at Goliad, and the men who charged the Mexican lines at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. Save for a county named after Moore in the Texas panhandle, an entire pantheon of naval heroes has largely been ignored. If one goes to Galveston, there are no statues of Commodore Moore, but one sees memorials to Heros of the republic who fought at San Jacinto and a monument to Confederate Heroes. On the streets, no mention of the Texas Navy, no Moore Avenue runs adjacent to the Strand. The Texas Navy is largely forgotten, erased from memory by a vindictive president.

LT Jason Lancaster is a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer. He is currently the Weapons Officer aboard USS STOUT (DDG 55). He holds a Masters degree in History from the University of Tulsa. His views are his alone and do not represent the stance of any U.S. government department or agency.

Bibliography

1.) Hill, Jim Dan, The Texas Navy, in Forgotten Battles and Shirtsleeve Diplomacy,

University of Chicago Press, 1937; reprint, State House Press, Austin, Texas, 1987, 224p.

2.) Wells, Commander Tom Henderson, USN, retired, Commodore Moore & The Texas Navy, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1960, second printing 1988, 218p.

3.) Douglas, Claude L, Thunder on the Gulf, or, The Story of the Texas Navy, Old Army Press, Fort Collins, CO, 1973.

4.) Francaviglia, Richard V., From Sail to Steam, Four Centuries of Texas Maritime

History 1500-1900, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, 1998, 324p. Company, 1936; reprint, Old Army Press, 1973, 128p.

5.) Meed, Douglas V., the Fighting Texas Navy, Republic of Texas Press, 2001, 250p.

6.) Devereaux, Linda Ericson, the Texas Navy, Ericson Books, Nacogdoches, Texas, 1983.

7.) Barker, Eugene, The Writings of Sam Houston, volumes I-VIII Pemberton Press, 1970.

8.) Barker, Nancy Nichols, The French Legation in Texas, volumes I-II Texas State Historical Association, 1973.

9.) Campbell, Randolph B, Sam Houston and the Southwest, Harper-Collins College Publishers, 1993.

10.) Sumida, Tetsuro Jon, Inventing Grand Strategy and Teaching Command: the Classic Works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Woodrow Wilson Center Press, Washington D.C. 1997.

11.) Mahan, A.T., the Influence of Sea Power upon History 1660-1783, Dover Publications, NY, 1987.

12.) Maberry, Robert Jr., Texas Flags, Texas A&M Press, College Station, 2001.

13.) Gulick, Charles Adams, Jr., the Papers of Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, volumes II-VI, AMS Press New York, 1972.

14.) Hollon, Eugene, W. William Bollaert’s Texas, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1956. The Campeche Campaign, 1843, Meed, pg 2. (Texas State Historical Association, Austin)

Texas Gulf Coastline, Francaviglia, Richard V., From Sail to Steam, Four Centuries of Texas Maritime History 1500-1900, pg 2. (Jeffery G Paine and Robert A. Morton, Shoreline and Vegetation-Line Movement: Texas Gulf Coast 197241882)

Endnotes

[1] Douglas, Thunder on the Gulf, pg 17

[2] Jim Dan Hill, The Texas Navy, pg 119

[3] Hill, pg 84

[4] Commander Tom Henderson Wells, Commodore Moore and the Texas Navy, pg 32

[5] John Tetsuro Sumida, Inventing Grand Strategy and Teaching Command, 1997

[6] Sumida, pg 48

[7] Campbell, 71

[8] Wells, pg 159

[9] Douglas V. Meed, The Fighting Texas Navy, pg 227

[11] Nancy Barker, The French Legation in Texas, Volume II, pg 489

[12] Randolph Campbell, Sam Houston, pg 112-113

Featured Image: On a street in London, England at 4 St James’s Street sits the building which at one time served as the site of the Embassy of Texas. From 1842 until 1845, when Texas became a state, this is where the Republic of Texas did business in England and across from St. James Palace. (Photo by Luke Spencer)