By David Scott

Introduction

On 4 September 2017, an Australian naval task group departed from Sydney and embarked on a unique deployment called Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 to participate in a series of key naval exercises with a variety of partners in the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea and the Pacific – i.e. the Indo-Pacific. Its commander, Jonathan Earley, oversaw six ships and over 1300 personnel, making it the largest coordinated task group from Australia to deploy to the region since the early 1980s.

The immediate purposes of the exercise were given by the Australian Department of Defence as two-fold; namely soft security “focused on demonstrating the ADF’s Humanitarian and Disaster Relief regional response capability, as well as hard security “further supporting security and stability in Australia’s near region.” The latter was described as demonstrating “high-end military capabilities such as anti-submarine warfare.” Geopolitically this reflected what the Defence Minister Marise Payne called “heightened interests in the Indo-Pacific” for Australia, with frequently recurring China-related considerations.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not comment on the Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 deployment. However, the Chinese state media was certain on Australian motives, running articles like “Australia-led military drills show tougher China stance” (Global Times, 7 September). In the article, Liu Caiyu argued that “Australia’s largest military exercises in the Indo-Pacific region show it has toughened its stance toward China, especially on South China Sea issues.” The People’s Daily wondered, pointedly, given this deployment into the South China Sea and East China Sea, “What does Australia want to do with the largest military exercise encircling China in 30 years?”

It was revealing that Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 was explained by the Australian Department of Defence as enhancing military cooperation with some of Australia’s “key regional partners”; specifically named as Brunei, Cambodia, the Federated States of Micronesia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and Timor-Leste. Politically the absence of China as a partner was deliberate but accurate, and in which the range of other countries represented a degree of tacit external balancing on the part of Australia.

The Itinerary

The naval group was led by HMAS Adelaide, Australia’s largest flagship, commissioned in December 2015. HMAS Adelaide was joined at various moments by HMAS Darwin (guided missile frigate), HMAS Melbourne (guided missile frigate), HMAS Parramatta (anti-submarine/anti-aircraft frigate), HMAS Toowoomba (anti-submarine/anti-aircraft frigate), and HMAS Sirius (replenishment ship). These units highlighted Australia’s unique Indo-Pacific positioning given it faces both oceans, as units from Fleet Base East at Sydney (HMAS Adelaide, HMAS Darwin, HMAS Melbourne, and HMAS Parramatta) and from Fleet Base West at Perth (HMAS Toowoomba and HMAS Sirius) participated.

The task force’s first engagement activity announced on 8 September was for HMAS Adelaide to conduct aviation training with USS Bonhomme Richard, a large American amphibious assault ship, on the east coast of Australia. HMAS Adelaide then completed further amphibious landing craft and aviation training with the Republic of Singapore’s amphibious ship, RSS Resolution while deployed further up the east coast of Australia off the coast of Townsville.

The first external port call was carried out on 20 September as HMAS Adelaide, HMAS Darwin, and HMAS Toowoomba steamed into Dili, the capital of East Timor, to deliver a portable hospital ahead of Exercise Hari’i Hamutuk. This engineering exercise involves Australian, Japan, U.S., and East Timor’s military forces working side-by-side to build skills and support East Timor’s development. This set the seal nicely on their reconciliation over claims in the Timor Sea, achieved when the two sides reached agreement at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague.

HMAS Parramatta proceeded northward to conduct joint patrols from 22-26 September with the Philippine Navy in the Sulu Sea, as part of the annual Lumbas exercises running since 2007. HMAS Parramatta sailed eastwards to Palau for a three-day stop from 22-24 September. Significantly Palau recognizes Taiwan (ROC) rather than Beijing (PRC) as the legitimate government of mainland China. A further extension saw HMAS Parramatta visit Yap on 27 September. Its stay at Yap included cross-deck training with the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) Patrol Boat FSS Independence, an Australian-gifted Pacific-class Patrol Boat. Both stops showed Australian naval outreach into the so-called “second island chain” (dier daolian) which Chinese naval strategy has long shown interest in penetrating, as with deployments of underwater survey vessels around the Caroline Islands in August 2017.

Meanwhile, HMAS Adelaide and HMAS Toowoomba paid a port call to Jakarta from 24-26 September. It was significant that this brought to an end a previous period of coolness between the two governments, at a time when Indonesia was becoming more assertive in its own claims over maritime waters in the South China Sea, renaming waters around the Natuna archipelago (which also fall within China’s 9-dash line) as the North Natuna Sea.

HMAS Adelaide and HMAS Parramatta then rendezvoused at the Malaysian port of Port Klang from 1-5 October to carry out joint Humanitarian and Disaster Relief exercises and demonstrations on 4 October. Relations with Malaysia have remained strong, anchored through the Australian presence at Butterworth Airbase under the Five Power Defence Agreement (5PDFA) and the bilateral 25-year old joint defense program between Australia and Malaysia.

Australian naval units then retraced their steps and entered the South China Sea. These waters are mostly claimed by China within its 9-dash line, which includes the Spratly Islands (disputed in varying degrees with Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Philippines and Vietnam) and with Beijing in control of the Paracels (disputed with Vietnam) since 1974. China viewed the arrival of the Australian Navy in the South China Sea with some unease, with the state media warning that the “Australian fleet must be wary of meddling in South China sea affairs” (Global Times, 24 September).

Having paid then a friendly port call to the small, oil-rich state of Brunei from 30 September to 2 October, HMAS Melbourne then moved up with HMAS Parramatta to Japan, where they arrived on 9 October to take part in the bilateral Nichi Gou Trident exercise with the Japanese Navy off the coast of Tokyo. The ships practiced anti-submarine warfare, ship handling, aviation operations, and surface gunnery. This exercise has been alternatively hosted between Australia and Japan since 2009. Security links with Japan have been considerably strengthened during the last decade since the Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation was signed in March 2007.

Simultaneously, further deployment into the Indian Ocean was carried out by HMAS Toowoomba which carried out a four-day goodwill visit to Port Blair from 12-15 October. Port Blair is the key archipelago possession of India dominating the Straits of Malacca and the Bay of Bengal, and the site for India’s front-line Andaman and Nicobar Command. Various joint exercises were carried out between the Indian Navy and Australian Navy. This reinforced the strengthening naval links between Australia and India, flagged up in the Framework for Security Cooperation signed in November 2014, and subsequently demonstrated with their bilateral AUSINDEX exercises in June 2017 off the western coast of Australia and in September 2015 in the Bay of Bengal.

Meanwhile, HMAS Adelaide and HMAS Darwin proceeded to the Philippines for a further goodwill visit from 10-15 October. Maritime links have been further strengthened of late with the donation of two Balikpapan-class heavy landing crafts by Canberra in 2015, and nominal-rate sale of three more in 2016. Australia’s concerns had been on show in Defense Secretary Marise Payne’s discussions in Manila on 11 September. These have been partly to bolster the Philippines against ISIS infiltration into the Muslim-inhabited southern province of Mindanao, but also to bolster the Philippines’ maritime capacity in the South China Seas against a rising China. With regard to the South China Sea, Australia has called for China to comply with the findings of the UNCLOS tribunal in July 2016, in the case brought by the Philippines, which rejected Chinese claims in the South China Seas.

HMAS Adelaide and HMAS Darwin then re-crossed the South China Sea to pay a port call at Singapore on 23 October. This maintains the regular appearance of Australian military forces at Singapore, which have been an ongoing feature of the 5 Power Defence Forces Agreement (5PDFA). While HMAS Darwin returned to Darwin, HMAS Adelaide paid a friendly port call at Papua New Guinea’s main port of Port Moresby on 11 November. Papua New Guinea is Australia’s closest neighbour, a former colony, and (like East Timor) the subject of Chinese economic blandishments.

HMAS Melbourne and Parramatta and a P-8A submarine hunter aircraft moved across from Japan to the Korean peninsula for an extended stay from 27 October – 6 November. This included their participation in the biannual Exercise Haedoli Wallaby, initiated in 2012, which focuses on anti-submarine drills with the South Korean Navy. This also reflected a reiteration of Australian readiness to deploy forces into Northeast Asia amid heightened tensions surrounding North Korean nuclear missile advancements. Naval logic given by the Task Group commander, Jonathan Earley was that “as two regional middle powers that share common democratic values as well as security interests, Haedoli Wallaby is an important activity for Australia and the ROK.” Wider trilateral activities were shown with the Melbourne and the Parramatta then carrying out anti-missile drills with U.S. and South Korean destroyers in the East China Sea on 6-7 November.

Australia’s Strategic Proclamations as Context

The general context for the Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 deployment was the explicit focus on the “Indo-Pacific” as Australia’s strategic frame of reference stressed in the Defence White Papers of 2013 and 2016, and rising concerns about China’s growing maritime presence.

This strategic context for the Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 deployment was elaborated at length by the Defence Minister Marise Payne at the Seapower Conference in Sydney on 3 October. Payne’s speech contained strong messaging on Australian assets, deployment, and the Indo-Pacific focus of Australian defense strategy.

With regard to assets, Payne announced and welcomed “the most ambitious upgrade of our naval fleet in Australia since the Second World War” to create “a regional superior future naval force being built in Australia which will include submarines, frigates, and a fleet of offshore patrol vessels.” She also noted her own pleasure in commissioning Australia’s “largest warship” (HMAS Adelaide, commissioned on 4 December 2015) and “most powerful” air warfare destroyer (HMAS Hobart, commissioned on 23 September 2017). Australia’s second air warfare destroyer, Brisbane, began sea trials off the coast of southern Australia in late November 2017. This current naval buildup could be seen as demonstrating external balancing, but of course this raises the question of external balancing against whom – to which the unstated answer is China.

With regard to deployments, Payne enthused on decisive opportunities for a fifth generation navy:

“Altogether these and those future capabilities will transform the Australian fleet into a fully operational, fifth generation navy. The RAN will be able to deploy task groups equipped with a wide range of capabilities, from high-end war fighting to responsive and agile humanitarian assistance … To envisage that future, high-end war fighting to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, we also only need to look at the ADF’s Joint Task Group Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 that’s currently underway in the Indo-Pacific region.”

Finally, the whole Indo-Pacific nature of Australian maritime strategy was stressed:

“From the Malacca, the Sunda and Lombok Straits to the South and East China Seas, many of the most vital areas of globalisation and sources of geopolitical challenge are in our backyard. If the twenty-first century will be the Asian Century, then it will also be the Maritime Century. Just as surely as the balance of global economic and military weight is shifting in the Indo-Pacific, so too is it focused on the waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. With established and emerging maritime powers across the region rapidly expanding their naval capabilities, the waters to Australia’s north are set to teem with naval platforms, the numbers and the strength of which has never been seen before […] In a crowded and contested Indo-Pacific maritime sphere, Australia must present a credible deterrent strategy, and to do our part in contributing to the peace, stability and security, and to good order at sea […] Our naval capabilities will therefore be integral […] to the preservation of the rules-based global order, and safeguarding peace in the maritime Indo-Pacific.”

China was not specifically mentioned but was the unstated reason for much of these Indo-Pacific challenges that Australia felt it had to respond to, with its behavior in the South China Sea frequently the subject of the strictures on maintaining a “rules based” order.

The South China Sea issue was on public view at the Australia-U.S.-Japan trilateral strategic dialogue (TSD) meeting on 7 August 2017 where Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop joined her Japanese and U.S. counterparts in expressing “serious concerns” over “coercive” actions and reclamation projects being carried out and urged China to accept the ruling against it by the UNCLOS tribunal. Finally they announced their intentions to keep deploying in the South China Sea, into what they considered were international waters. In June 2017, Australia had already joined Japan, Canada, and the United States for two days of military exercises in the South China Sea.

As Vice Admiral Tim Barrett, Australia’s Chief of Naval Staff, noted in his speech on “Law of the Sea Convention in the Asia Pacific Region: Threats, challenges and opportunities,” despite “the increasingly aggressive actions taken by some nations to assert their claims over disputed maritime boundaries …[…] the Navy will continue to exercise our rights under international law to freedom of navigation and overflight.” Australian commentators were quick to point out its significance. In effect China was in mind as a threat and challenge. Although Australia has not taken a formal position on rival claims on South China Sea waters, it had strongly criticized Chinese reclamation projects and military buildups in the South China Sea, hence Global Time articles like “South China Sea issue drags Sino-Australian ties into rough waters” (20 June 2017).

Even as Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 units ploughed across the Western Pacific, Australia officials joined their U.S., Japan, and Indian counterparts on 12 November in a revived Quad format on the sidelines of the ASEAN summit. Australian concerns, shared with its partners, were clearly expressed by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT): “upholding the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific and respect for international law, freedom of navigation […] and upholding maritime security in the Indo-Pacific.” The official Chinese response at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was minimal, “we hope that such relations would not target a third party” (14 November), followed by sharper comments in the state media on Australian participation being unwise (Global Times, “Australia rejoining Quad will not advance regional prosperity, unity, 15 November). The so-called Quad had emerged in 2007 with meetings between officials on the sidelines of the ASEAN summit, with Australia joining in the Malabar exercises held in the Bay of Bengal by India, Japan, and the U.S. Australia subsequently withdrew from that format, though continuing to strengthen bilateral and trilateral naval links with these other three partners. This renewed Quad setting is likely to see Australia rejoin the Malabar exercises being held in 2018.

It was no surprise that this Indo-Pacific setting was reinforced with the Foreign Policy White Paper released on 23 November with its listing of “Indo-Pacific partnerships” in which “the Indo–Pacific democracies of Japan, Indonesia, India, and the Republic of Korea are of first order importance to Australia” as “major partners.” China’s absence from this listing of Indo-Pacific partners was revealing. Balancing considerations were tacitly acknowledged in the White Paper:

“To support a balance in the Indo–Pacific favourable to our interests and promote an open, inclusive, and rules-based region, Australia will also work more closely with the region’s major democracies, bilaterally and in small groupings. In addition to the United States, our relations with Japan, Indonesia, India, and the Republic of [South] Korea are central to this agenda.”

China was again absent from this listing, which was no surprise given how the White Paper noted that “Australia is particularly concerned about the unprecedented pace and scale of China’s activities. Australia opposes the use of disputed features and artificial structures in the South China Sea for military purposes.” In China this was immediately rejected by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as “irresponsible remarks on the South China Sea issue. We are gravely concerned about this…” and also in the state media (Global Times, “China slams Australian White Paper remarks on South China Sea,” 23 November). This explains the extreme sensitivity China had shown over the Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2017 deployment into the South China Sea.

Conclusion

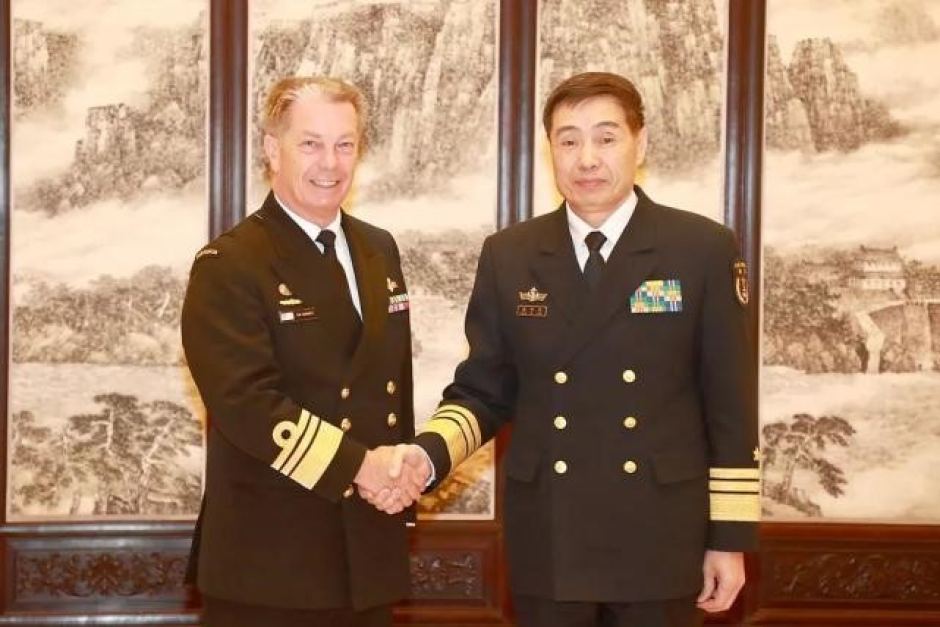

Consequently 2017 ended by palpable Australia-China maritime friction, when China’s Ministry of Defense gave details of discussions between China’s Navy commander Shen Jinlong and his Australian counterpart Vice Admiral Tim Barrett. The Chinese statement said that “in the last year, the Australian military’s series of actions in the South China Sea have run counter to the general trend of peace and stability. This does not accord with … forward steps in cooperation in all areas between the two countries.” In retrospect Australia’s maritime strategy shows itself to be primarily Indo-Pacific oriented, with its increasing concerns over China generating a response of external balancing through naval exercises and cooperation with India, Japan, the U.S., and a multitude of other partners, and with an increasing focus on restraining China in the South China Sea. China has been upset.

David Scott is an independent analyst on Indo-Pacific international relations and maritime geopolitics, a prolific writer and a regular ongoing presenter at the NATO Defence College in Rome since 2006 and the Baltic Defence College in Tallinn since 2017. He can be contacted at davidscott366@outlook.com.

Featured Image: HMAS Adelaide sails the Timor Sea to deliver a mobile hospital to Dili, Timor Leste, as part of a multi-national Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief exercise. (Australian Ministry of Defence photo by LSIS Peter Thompson)

It is becoming increasingly evident that the Indo of the Indo-Pacific ends at the eastern edge of the Indian mainland viz the Bay of Bengal for the USN, RAN etc. The vast expanse of the Indian Ocean which incidentally is India’s primary area of responsibility does not figure in this construct. In any case other than the US Navy and now the PLA Navy, none of the other navies from thje east of Malacca have the wherewithal to project power in the IO. Hence in the inevitable confrontation in the IO between the Indian Navy and a possible PLAN-PN combine a few years down the line, I wonder what the IN can expect from the emerging maritime security construct amongst the maritime democracies of the ‘Indo-Pacific’.