By Dmitry Filipoff

Series Introduction

“Fleet level processes and procedures designed for safe and effective operations were increasingly relaxed due to time and fiscal constraints, and the ‘normalization-of-deviation’ began to take root in the culture of the fleet. Leaders and organizations began to lose sight of what ‘right’ looked like, and to accept these altered conditions and reduced readiness standards as the new normal.” –2017 Strategic Readiness Review commissioned in the aftermath of the collisions involving USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and USS John S. McCain (DDG-56)

The U.S. Navy is suffering from self-inflicted strategic dysfunction across the breadth of its enterprise. This series seeks to explore the theme of the normalization of deviation in some of the most critical operations, activities, and attributes that prepare the U.S. Navy for war. Because the U.S. Navy is the senior partner in its alliance activities many of these problems probably hold true for allied navies as well.

Part One below looks at U.S. Navy combat training and draws a comparison with Chinese Navy training.

Part Two will examine firepower relating to offense, defense, and across force structure.

Part Three will look at tactics and doctrine with an emphasis on network- and carrier-centric fleet combat.

Part Four will discuss technical standards.

Part Five will look at the relationship between the Navy’s availability and material condition.

Part Six will examine the application of strategy to operations.

Part Seven will look at strategy and force development, including force structure assessment.

Part Eight will conclude with recommendations for a force development strategy to refocus the U.S. Navy on the high-end fight and sea control.

Combat Training

“This ship is built to fight; you’d better know how.” –Former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke (ret.) at the commissioning ceremony of the destroyer USS Arleigh Burke (DDG-51)

The training strategy of a military service is one of its most fundamental responsibilities. Training is central to piercing the fog of war as much as possible before combat exacts its price. Training is what forges people into warfighters.

Soon after the Cold War ended the Navy announced a “change in focus and, therefore, in priorities for the Naval Service away from operations on the sea toward power projection.”1 A new operating focus on low-end missions such as partner development missions, striking land targets, and deterring rogue regimes came to dominate its focus. Different training followed. This training and operating paradigm replaced the high-end threat focus the Navy was originally made for in an era of great power competition against the Soviet Union. But the shift was wholesale, and did not attempt to preserve a responsible minimum of important skills that still held relevance. Perhaps worst of all, somehow this shift allowed U.S. Navy training to fall to incredible lows and remain there for most of a generation.

So much valuable corporate memory has evaporated. Extremely unrealistic training exercises starved Sailors of opportunities to learn important skills and prove themselves. And while the U.S. Navy slipped for years its latest rival, the Chinese Navy, made strong gains in the very same skills the U.S. Navy was losing.

Realism and the Nature of U.S. Navy Exercising

“The mission of the fleet in time of peace is preparation for war, and in this preparation tactical training heads the list of requirements…No matter how perfect we are in every other respect, if we cannot make good here we might as well not exist.” –Captain William S. Sims, “Naval War College Methods and Principles Applied Afloat,” 1915.

For years the Navy’s training exercises took on a scripted character where the outcomes were generally known beforehand and where opposing forces were usually made to lose. Scripted training is not inherently wrong if it is used as a stepping stone to more open-ended and complex exercises. However, such events were very few and far between. As a result most U.S. Navy high-end combat training remained stuck at an extremely basic level that barely scratched the surface of war. As a report from the Naval Studies Board described Navy training, “There is little free play, and exercises are typically scripted with little deviation allowed.”2

One of the most important methods of making exercises realistic is facing off against opponents that can win. Going up against a thinking and capable adversary creates a level of challenge that simple target practice cannot approach. Red teams and opposing forces can be highly specialized units that incorporate key intelligence insights to make their behavior more like that of a foreign competitor. Opposing forces can also be more simple when using scratch teams where training units can be divided into opposing sides and told to challenge each other. Scratch opposition forces are not as realistic as using teams informed by intelligence on competitors, but scratch teams can pose a real challenge because it is still troops competing against troops.

It appears Navy exercising was devoid of opposition forces that stood a chance. In “An Open Letter to the U.S. Navy from Red,” Captain Dale Rielage, the intelligence director of U.S. Pacific Fleet, writes from the perspective of an opposing force commander to the U.S. Navy and offers insight into how the Navy minimized challenge in its training by handicapping its Red teams:

“Your opposing forces often are very good, but you have trained them to know their place…our experience is that they have learned to self-regulate their aggressiveness, knowing what senior Blue and White cell members will accept. As one opposing force member recently told us during a ‘high-end’ training event, their implied tasking included not annoying the senior flag officer participating in the event. They knew from experience that aggressive Red action and candid debriefs were historically a source of annoyance. They played accordingly.”3

Rielage invoked the infamous Millennium Challenge exercise. This exercise was a massive warfighting experiment that became a controversy after the opposing force commander Lt. Gen Paul van Riper quit in protest. Riper at first inflicted devastating losses on the Blue team through unconventional means, but subsequent rounds cemented parameters that forced Red to lose.4 According to Rielage, “The entire event generally is remembered as an example of what not to do…The reality is that we repeat this experience on a smaller scale multiple times each year.”

Rielage then goes on to suggest the problem is extremely pervasive and longstanding:

“You talk about accepting failure as a way to learn, but refuse to fail. It is instructive to ask a room of senior officers the last time they played in—or even heard of—a game or exercise where Red won.”

If the Red teams of Navy exercising are so constrained they rarely ever win then what are they being used for? Admiral Scott Swift, recent commander of U.S. Pacific Fleet, gives a clue in “A Fleet Must be Able to Fight.” Swift points out that “Our warfighting culture focuses on kill ratio—the number of enemy losses we can inflict for every loss we take.”5 However, Navy exercising usually results in extremely favorable tradeoffs. Swift argued that the Navy’s “reliance on high kill ratios” causes it to focus on “exquisite engagements,” or “firing from a position of minimum uncertainty and maximum probability of success (emphasis added).” Swift concludes that in high-end operations “it is not possible to generate the number of exquisite engagements necessary to achieve victory.”

Warfighting culture is a product of training. If the Navy’s warfighting culture was focused on easy (“exquisite”) engagements that always earn high kill ratios then perhaps the reason opposing forces almost never won is because they were relegated to the role of cannon fodder.

One example of Red teams being used for simplistic target practice is seen in how submarines were often pitted against warships. Only three years ago did the surface fleet finally open a fully integrated tactical center of excellence for itself, the Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC, or the TOPGUN of the surface fleet as they often say), whose responsibilities include improving training and tactics.6 One SMWDC commander spoke of how the Navy was using the surface fleet as an opposing force to train submarines in certain exercises, where according to Admiral John Wade, “Up until two years ago, surface ships were kind of just targets…They told you to go drive from Point A and Point B…The submarines were just crushing us.”7

How else can one reduce an opponent to easy prey? The Navy accomplished this in part through a linear style of training. Navy training took the form of a series of events that focused on individual warfare areas. These include mission areas such as anti-air warfare, anti-surface warfare, and anti-submarine warfare. Exercise and certification events mainly focused on working only just one skillset at a time. Admiral Swift suggested Navy training amounted to “ticking off a discrete schedule of individual training objectives” and argued that this is why the Navy could not execute critical warfighting tasks with confidence. While the Navy did manage to train individual skills, “…we as a force never practiced them together, in combination with multiple tasks…”8

This limits the freedom to play an accurate opposition force. Capt. Rielage remarked that Red teams are most often constrained and used to only “perform a specific function to facilitate an event” (such as an individual training certification event) rather than behave like a thinking adversary.

Many naval platforms are multi-domain in nature, with the ability to attack targets in the air, on the ocean, and beneath the surface. Cross-domain fires are the norm in war at sea, such as how a submarine can fire missiles at a ship from underwater. Sinking a modern warship is at least a matter of knowing how to fight targets on the surface and in the air at the same time, simply because ships can fire missiles at each other. Naval warfare involves sensors and weapons that can reach out to hundreds of miles from a single ship. The scale of this multi-domain battlespace can be enormous while containing numerous types of threats. Through this complexity war at sea can be filled with an incredible scope of possibilities and combinations. Even in an era absent great power competition rogue regimes like Iran still field multi-domain capabilities such as submarines and anti-ship missiles. Practicing only one skillset at a time using cannon fodder opposition forces that almost never win barely scratches the surface of war, yet this is exactly how the U.S. Navy has been training its strike groups for years.

In recent decades it appears the Navy did not have a true high-end threat exercise until Admiral Swift instituted the Fleet Problem exercises two years ago.9 It must be recognized that because the Fleet Problems are so new they still may not accurately represent real war. Instead, they simply set and combine the basic conditions to present a meaningful challenge to train for the high-end fight.

The Fleet Problems are large-scale, long-duration, and open-ended events. Large-scale, in that the unit being tested can be a strike group or larger; long duration, in that the exercise is at least several days long instead of less than 24 hours; open-ended, in that they give wide latitude to the troops involved rather than narrowly constraining them to execute proscribed methods.10 Perhaps most critically, the Fleet Problems include an opposition force that is capable of inflicting painful losses. They also force the Navy to exercise multiple warfighting areas in combination rather than one at a time, which was the standard design for the Composite Unit Training Exercise (COMPTUEX) that was considered the peak of high-end sea control training in every deploying strike group’s workup cycle.11 The novelty of the Fleet Problems suggests the Navy’s overseas exercises on deployment were not much better. While these individual training conditions are not totally unprecedented in the Navy the Fleet Problems appear to be the first events in many years to effectively combine them on a large scale.

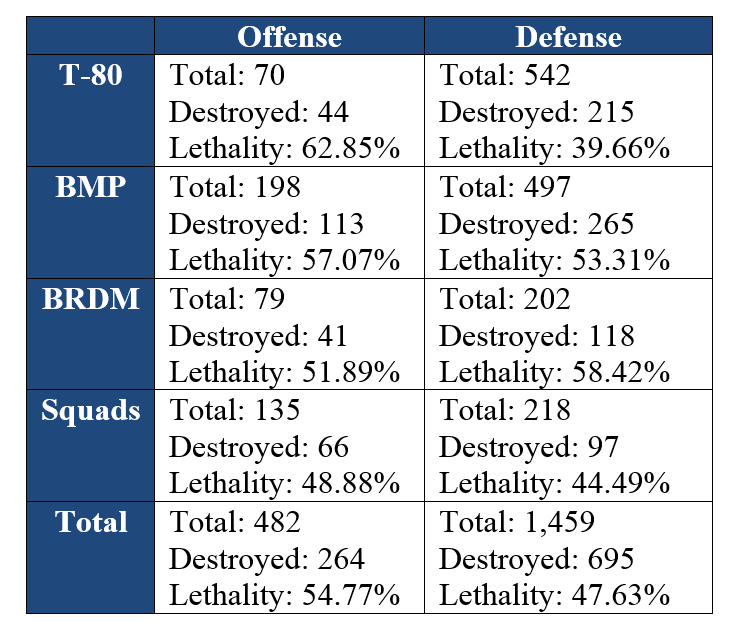

Before the Fleet Problems the Navy’s training system stood in stark contrast to the exercise programs of other branches. Both the Army and the Air Force are keenly aware of the need to use dedicated and capable opposition forces to hammer warfighting competence into their units through high-end threat training.12 Hundreds of aircraft participate annually in the Air Force’s Red Flag exercise where opposing aggressor squadrons often impose high cost. Nearly a third of the Army’s brigades rotate every year through the National Training Center (NTC) at Fort Irwin where Army units are regularly challenged by dedicated opposition forces. The table below shows how Army Brigade Combat Teams do not always score high kill ratios at the NTC.13

The National Training Center and Red Flag exercises have existed for decades and are among the highest priorities for their respective military branches. Evolving real-world threats frequently combine with new technology to introduce fresh challenges into these capstone training events. Yet in spite of everything that was changing about the Navy’s technology and advances being made by foreign competitors the Navy’s premier pre-deployment exercise stagnated. Admiral Phil Davidson suggested, “we’ve made more changes during the last 18 months to COMPTUEX than in the last 18 years.”14

The problem of military training becoming so scripted that victory is assured is not unprecedented. The Marines also have some history with this issue. In 1990, Marine William Bradley blasted the Corps for unrealistic training, questioning exercises that “smack of ‘zero defect’ artificiality,” and charging “who among us can say he has participated in major exercises where ‘success’ was not artificially preordained?”15 More recent writing suggests that opposing forces in the Marine Corps have been often made to simply “die in place.”16

Scripted training might come from some organizational pathology born from a zero-defect culture, a failure to evolve target practice into something that resembles dynamic battle, or some other combination of complacence and lack of imagination. What is certain is that it bears little resemblance to the sort of wars the military of a superpower can be asked to fight.

The Navy has made moves in the right direction only recently though much of Navy training probably remains a heavily scripted affair. Truly difficult exercising for the high-end fight at the strike group level has begun with the advent of the Fleet Problems. COMPTUEX is becoming more challenging, although through more virtual means.17 Two years ago SMWDC instituted a new training event called Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training (SWATT) that finally gives the surface fleet its own integrated training phase prior to joining capital ships for larger events in the workup cycle.18

Given how new they are however the extent to which the Navy will sustain and make the most of these activities remains unclear. What is certain is that they are taking place within a context and a culture shaped by a generation of neglect. As Admiral Swift succinctly put it, “There is no classroom instruction and little doctrine or guidance for fighting a fleet.”

The Structure of U.S. Navy Training

“Peacetime maneuvers are a feeble substitute for the real thing; but even they can give an army an advantage over others whose training is confined to routine, mechanical drill.” –Carl von Clausewitz, On War.

After deploying beyond its means for years the Navy was facing unsustainable growth in maintenance backlogs, yet rising demand for naval power meant the Navy would hardly budge on delaying deployments. As ships went through their usual phases within the workup cycle to prepare for deployment something had to give as pressure built from both sides. Navy leadership characterized the situation as a “rise in operational demand, maintenance availabilities going long, and training getting squeezed in the middle.”19 According to Navy officials cutting weeks of training became the preferred remedy to get ships out on time.20

Cutting training time is not necessarily wrong however because training could go on forever. Even with cuts ships still have months of time devoted to training within the workup cycle and more opportunities when deployed. The Navy cannot blame operational demand or maintenance backlogs alone for compressed training. Instead, it is the fault of poor decision-making on how to structure the training process and assume risk.

Sailors feel constantly rushed while training, especially within the workup cycle, because they are being forced to do hundreds of training events in order to satisfy an impossible number of requirements that only seems to grow.21 As training and certification events grew more numerous they were forced to become more shallow because they were stuffed into fixed or even shrinking timeframes. As the Naval Studies Board lamented, “There are no empty blocks on the exercise and training schedules.”

Time pressures encouraged scripted events because training can be passed more quickly. Hard training involves repeat attempts after failure, a larger selection of open-ended scenarios, and a thorough after-action review process. All of these things cost time. Scripting can help make time for more events and cut corners when needed. Scripted training became an important means to help Sailors stay on schedule in a system that was overburdened with too many requirements.

These excessive requirements come from a desire to cover too many bases. A warship, being an advanced machine, can experience technical failure and take damage in numerous ways. Ships can also be employed in a wide range of missions. Training to manage the degradation of a ship and the complexity of naval warfighting is an incredibly difficult task. However, it is impossible to train to every kind of scenario or prevent every kind of failure. A training system represents calculated risk where strong proficiency in some areas must come at the expense of skill in many others.

An example of poor risk calculation with respect to tactical training can be seen in the submarine force where according to LT Jeff Vandenengel:

“…virtually every officer on board can explain complex engineering principles, draw diagrams of entire reactor systems, and have conducted countless complex engineering-casualty drills, but few to no simulated attacks on an enemy warship. So much time, energy, and effort is spent on engineering issues that the study, development, and practice with tactical systems and techniques are often treated like afterthoughts.”22

The Navy has allowed the technical complexity of its ships and the flexibility of naval power to overwhelm the ability of Sailors to effectively train for war. Miscellaneous administrative burdens have also ballooned. Risk aversion has been mistaken for due diligence where a risk averse culture prone to adding training and inspections sought to mitigate risk that should have been accepted. Now it has become impossible to expect Sailors to become skilled at core warfighting tasks when there are too many boxes to check.

The training certification system has become so backward it is inhibiting the very sort of skill it should be promoting. According to Vice Admiral Joseph Tofalo, recent commander of the U.S. submarine force, they were “…really working hard by taking a hard scrub of our assessment and certification process” just to make only 10-15 days’ worth of time to insert high-end threat training into the months-long workup cycles of submarines.23 The bloated certification system is suffocating the ability of senior leaders to implement meaningful training reform.

But even with a bloated system why is it such a struggle for the Navy to make so little time for one of the most important types of training there is?

Training and Evaluation

“You cannot allow any of your people to avoid the brutal facts. If they start living in a dream world, it’s going to be bad.”–James Mattis

Most of the Navy’s training is not actually training in the fullest sense of the term. Rather, most events appear to be readiness evaluations. The intent of a readiness evaluation is not necessarily to create an in-depth learning experience, but to pass an event and earn a certification that indicates a unit is competent at a certain task. The term “certification” is almost always used in relation to the intent and end result of Navy training. Sailors in the fleet are often worrying about maintaining their numerous certifications because they require periodic refreshing.

Good training is about pushing to failure, testing limits, and taking risk head on. This makes it necessary to have training events that do not culminate in a pass/fail evaluation that can reflect poorly on a participant. When under evaluation one will likely fall back on previously known methods instead of using the opportunity to try something new. By frequently conflating readiness evaluations with training the Navy has failed to create enough space where Sailors can safely experiment and learn from their mistakes.

A singular focus on certification can encourage scripting because the goal simply becomes passing the next event rather than genuine improvement over time. Scripting away risk makes the chances of passing certification events much better. Yet much of the point of military skill is in knowing how to manage violent risk.

The Navy’s scripted style of training calls the trustworthiness of the certification system into question. In reference to unit-level training LT Erik Sand described a training and reporting system that allowed for “easy gaming and cheating” and that “because ships design their own drills, they can hide their weaknesses.” Ships were able to write the training packages they would be evaluated on and rehearse them enough to minimize surprise in advance of their inspections. LT Sand felt compelled to argue for the obvious: “In combat, a ship cannot pick where she takes a hit. The crew should not be able to do so in an inspection…the ship’s crew should not have specific foreknowledge of drill scenarios.” The end result was not an inspection process that seriously tests warfighting skill, but instead “evaluates the crew’s ability to stage-manage a show.”24

The quality of any certification is based on the standard of training it was earned through. How credible is a warfighting certification earned through scripted training?

Comparing Chinese Navy Training

“He who can modify his tactics in relation to his opponent and thereby succeed in winning, may be called a heaven-born captain.” –Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Winning is not about being the best, but simply being better than the opposition. In this vein, how does the U.S. Navy stack up against its chief rival, the Chinese Navy?

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) regularly releases unclassified reports on foreign navies. Its reports on the Chinese Navy (People’s Liberation Army Navy – PLAN) criticize training shortcomings that the U.S. Navy is itself committing. However, these reports also paint a picture of a force that is serious about training harder and working to overcome past disregard for realism.

In its 2015 report ONI stated the PLAN is “rectifying training methods by avoiding formalism and scripting in exercises.”25 As it looks to improve, less scripted training events that aim to “stress tactical flexibility, are occurring on a regular basis…” ONI’s 2007 report indicates the PLAN was making similar reforms earlier. The report said a limitation of the PLAN was its “reliance on scripted training events” and that new training guidance emphasized opposition force training and injecting surprise. In what the PLAN calls Naval Combat Readiness Exercises the exercise plan is “kept from the unit being exercised until just before orders are issued, or until the warning or signal is given.”26 The 2015 report said that a key goal of opposing force training exercises happening “on a regular basis” is “to evaluate a leader’s ability to develop and execute operational plans according to loosely defined objectives.”

Compare this to how Admiral Swift described the reaction of U.S. Sailors being presented with a Fleet Problem exercise: “Some teams clearly were uncomfortable, looking for the gouge on how the problem would go down. Many seemed astonished that the part of the order tasking them (‘Here is my intent. Your charge is to develop the required tasks to achieve it.’) often was less than a page long.” Swift said the fleet staff had to urge these leaders several times to “Stop asking for the plan; plan your solution.”27

The 2007 ONI report noted that “Typically, PLAN units previously conducted only one training subject per sortie in a building block approach” and that under new training standards units “now conduct more than one training subject per sortie.”

Compare this to how Admiral Swift described Navy training in his recent writing, in that “Much of the process of unit training certification consists of performing individual techniques, often in a set sequence and a reduced tempo. In a fight, these techniques need to be combined and executed with speed.”

In addition to being chief of intelligence for U.S. Pacific Fleet Captain Rielage also serves as the senior member of the Pacific Naval Aggressor Team (PNAT) that was created a few years ago.28 PNAT seeks to incorporate intelligence insights on adversaries to create accurate representations of their thinking and behavior. PNAT then puts these insights into practice by leading opposing forces in certain events such as the Fleet Problems where Admiral Swift says PNAT “frequently surprises” leaders all the way up to the four-star level “unlike current strike group training.”29 Capt. Rielage also has interesting insights into how Chinese Navy training is evolving.

In “Chinese Navy Trains and Takes Risks” Rielage writes that PLAN units often engage in force-on-force exercises that incorporate key elements of surprise such as where live opposing forces do not know the “exact composition or disposition of the adversary.”30 Units that exercise initiative to increase the difficulty of their training events are regularly praised in official PLAN media. According to Rielage, “The clear impression is that the PLAN is more willing to accept risk in its training evolutions than its U.S. counterparts.”

There is also a stark difference in the sort of missions the U.S. Navy and the Chinese Navy are focused on training for. Rielage claims the PLAN is “underpinned by an institutional emphasis on training for high-end naval warfare” and that “there is a strong argument that success in this mission is the PLAN’s primary and defining priority.” Compare this to how Admiral Swift characterized U.S. Navy training in the power projection era:

“A quick glance at a Composite Training Unit or Joint Task Force exercise schedule showed maritime interdiction operations, strait transits, and air wings focused on power projection from sanctuary. But despite the best efforts of our training teams, our deploying forces were not preparing for the high-end maritime fight and, ultimately, the U.S. Navy’s core mission of sea control.”31

For years the U.S. Navy has not tried to practice destroying modern fleets, but the Chinese Navy has.

The importance the PLAN places on training is also reflected in its leadership. While serving as Commandant of the Naval Command College and prior to becoming the current chief of the PLAN Admiral Shen Jinlong helped create a “Blue Force Center” that seeks to improve the realism of opposition force training. Earlier in his career he served as director of a naval vessels training center and was credited for establishing a training system for new-type ships.32 The current leader of the Chinese Navy is no stranger to training innovation.

The rate of tactical learning in the PLAN compared to most other navies is especially high, and not just because of its training values. With a hint of condescension the 2015 ONI report said that before the PLAN expanded its distant operations in 2009 it was “largely a training fleet, with very little operational experience.” But a force focused on hard and realistic training can certainly be effective when it will count most in war. The PLAN still has very few steady overseas commitments, and can afford to spend the bulk of its readiness on force development just like the interwar period U.S. Navy.33 On the other hand the modern U.S. Navy is stretched thin across the globe, and chooses to spend most of its readiness on overseas operations which are not the same as focused force development conducted close to home. The American and Chinese Navies have been spending their time on very different priorities.

Regardless of where they stand in relation to one another on the continuum of military excellence it appears the Chinese Sailor is learning and becoming a more lethal professional at a rate that far outstrips his American rival.

Training and Satisfaction in the Profession of Arms

“If we fight our fleets in mimic fights against each other, every officer and seaman, and fireman, and ward-room boy will understand enough to become interested. What we need more than anything else is to make our people interested…certainly no profession gives the opportunities for continued interest that ours does…yet is there anything more heartbreaking in its dullness than a man-of-war is often made to be!” –Commander Bradley A. Fiske, “American Naval Policy,” 1905.

A key distinction between institutions that provide security and most other organizations is that they rarely get to apply the full scope of their potential until an immediate threat demands a response. Most other organizations operate under a steady grind where they regularly apply foundational skills and often in direct competition against many others who are doing the same. Until an imminent threat appears an organization focused on security must remain in a self-imposed state of vigilance. This comes with unique challenges of promoting professional satisfaction and morale.

Being a sentry, as important as that may be, is hardly gratifying. The logic of promoting deterrence is often not tangible enough to be professionally fulfilling on its own to most who wear the uniform. After spending an ungodly amount of time filing paperwork, attending sessions, and conducting so many other preparations warfighters crave the opportunity to do their job and put their skills to the test. An organization focused on security should conduct hard training not only for the sake of preparedness but to give its people opportunities to push their limits and enjoy the fulfillment of becoming a better professional. In the absence of a pressing mission that demands the immediate use of specialized skills a focus on growing those skills is the next best thing.

While the Navy featured prominently at the opening of many campaigns and saved lives in humanitarian disaster the emphasis on low-end missions and training hardly helped Sailors experience the full potential of the powerful Navy they joined. The power projection era precluded Sailors from practicing many of the core high-end missions and skills a superpower Navy is usually built for, yet Sailors were still responsible for the extensive maintenance that high-end capability required. Scripted training under the bloated certification system has turned most tactical training into just another chore on a checklist rather than a stimulating exercise that focuses on quality learning and professional development.

The professional development opportunities that come with joining the most powerful Navy should be especially unique. In how many places can someone practice warfighting skills and operations using some of the most advanced warships ever made? How many jobs allow someone to become the best in the world at taking command of the seas through skill of arms? Surely there is some connection between the level of opportunity to grow as a better warfighter through hard trials and the unique job satisfaction that comes with being a military professional. Has the Navy harmed retention and morale by letting too many requirements, inspections, and low-end missions crowd out time for hard training? Clearly people joining the Navy would much rather be “forged by the sea” instead of forged by their inbox.

Training and Human Capital in the Profession of Arms

“…I would argue that nothing takes precedence over the peacetime commander’s job of finding combat leaders.” –Captain Wayne P. Hughes, Jr. (ret.), Fleet Tactics, Theory and Practice

The training certification system is unable to maintain a consistent standard across the force because luck plays an important role in how well the American Sailor gets trained. The fixed nature of the workup cycle and the variety of deployment experience create a roulette wheel of training opportunity. A Sailor can report to a ship only to spend the entirety of their assignment stuck in drydock with limited operating time. A Sailor that happens to report aboard closer to a deployment will have far more opportunity to conduct at sea operations, especially integrated training within a larger group of ships.34 One Sailor can deploy to mainly exercise with numerous third world navies while another’s deployment can feature exercises with more capable allies. The nature of the workup cycle and the variety of overseas experience sends a hodgepodge of training experience throughout the Navy’s ranks. This creates the need for major training events that are disconnected from the deployment cycle to better standardize proficiency. By the time a combat arms leader becomes a general officer in the Army or Air Force they have usually paid multiple visits to Red Flag and the National Training Center across their career.

While machines reflect learning as they grow in capability corporate memory is mainly carried forward by people. In this respect the Navy’s wholesale shift toward power projection not only inhibited its ability to practice war well, but failed to preserve a responsible minimum of institutional memory for full-spectrum competence. As Cold War-era personnel retired and separated from the service the Navy hemorrhaged skills and experience born from a time of better warfighting standards.35 Those with Cold-War era experience who still serve today saw their tactical skills atrophy under a new strategic focus. The result is that on average American Sailors know far less about high-end combat and sea control than they did 30 years ago. An organization that often describes its training in terms of “reps and sets” should have also understood the concept of use it or lose it.

American Sailors can put their training into a different “reps and sets” context. How many times have they run the exact same scenarios? How many times have they seen a live opposing force defeat a strike group? Are scripted exercises the defining training experience of a generation of American Sailors? In a system where everyone gets a trophy it is hard to know who is any good.

But training should not always be about winning or passing a test. Training is supposed to be a learning experience where failure is welcomed as an opportunity to learn and further prove oneself. Scripted training inhibits arguably the most important part of the training process – the after-action review. In the after-action review troops are expected to confront their mistakes, reflect upon alternatives, and contemplate their thought process. Without failure or the fear of future failure there will be less to question and reflect on. A solid after-action review process is necessary to give people a space where they can distinguish themselves as learners.

The after-action review of a training exercise can be a most humbling experience for the military professional where leaders are forced to take responsibility for mistakes that would have gotten their people killed in war. How a leader accounts for such consequential errors can reveal something about their command philosophy and leadership style. There is also a large difference in taking responsibility for failure within view of hundreds if not thousands of participating Sailors after a live exercise versus a virtual wargame that is played in the company of only a handful of fellow officers. The highly concentrated nature of modern naval capability and authority has given the enlisted Sailor virtually no ability to shape his or her fate through tactics in high-end war at sea.36 It is on the ship’s officers to know how to fight well for the sake of everyone else aboard.

Scripted exercises inhibit the warfighter’s ability to develop the unique professional skills critical to success on the battlefield. These special skills can range from employing warfighting techniques and tactics, maintaining unit cohesion while taking heavy losses, and knowing how to gamble with equipment and lives. Skillfully managing the chaos of war favors certain personal qualities such as the utmost candor, open-minded thinking, and a willingness to push to failure. These traits hardly describe the character of heavily scripted training. Without hard combat trials one cannot prove skill and virtue in ways only a warfighter can.

What scripted exercising has done to the Navy is damage its ability to discover those within its ranks who best exemplify the profession of arms.

Rudderless

“After their examination, the recruits should then receive the military mark, and be taught the use of their arms by constant and daily exercise. But this essential custom has been abolished by the relaxation introduced by a long peace. We cannot now expect to find a man to teach what he never learned…” –Vegetius, De re militari

If the most important peacetime military mission is to realistically prepare for war then what happens if this primary mission does not act to unify effort across the enterprise? Compared to all other peacetime operations exercises are the activity that come closest to real war which makes them an indispensable foundation for force development.37 Realistic exercising is what best integrates and filters the vital functions that evolve training, tactics, and doctrine. Exercises are also some of the best means for investigating the changing character of future war as technology evolves. The lack of realistic exercising is much more than an issue of questionable operator skill. It is a broader developmental problem for how the Navy is deciding its future.

It should go without saying that trying things in the real world under challenging conditions is how to mold vision into reality. The choice to disregard realistic exercising for a generation overlapped with a time when evolutionary ideas and networking capabilities were hitting the fleet. As the Information Age excited the imagination the Navy hailed transformative warfighting concepts such as ForceNet and AirSea Battle, but to the average Sailor these concepts changed little. There never was any serious AirSea Battle training, network-centric warfighting doctrine, or exhaustive tactical development for new major capabilities like CEC.

The Navy certainly made an effort to transform, but progress and proficiency should never be measured by how many new capabilities come online, CONOPs or TACMEMOs that get published, or wargames that get played. If these things are to have life then they must be taught to and refined by those charged with their execution. Real progress and skill is best defined by what the Sailors and commanders on the deckplate know how to do well, and for that there is only training. Because warfighting concepts did not translate into new and realistic force-wide training many of the Navy’s most ambitious efforts to transform can safely be described as stillborn.

If the Navy’s standards of exercising have been so poor for so long then it is natural to be skeptical of other elements of force development that feed into one another such as wargaming and test and evaluation. The functional linkage between strategy, tactics, and technology demands that force development activities use a shared set of realistic standards that evolve together to pace threats. Excessively scripting the one activity that comes closest to real war means failure was not a meaningful force of change for much of the naval enterprise. Clearly many unhelpful things have made it into the fleet if realistic exercising was not there to set a standard, serve as a proving ground, and anchor the Navy’s focus on warfighting.

What makes the Fleet Problem exercises and SMWDC key drivers of change is not that they are some special evolution of ongoing activity. Instead, finally the Navy has a challenging high-end exercise, and finally the surface fleet has a command that integrates the surface warfare enterprise for the sake of tactical development. And when key things that should have existed are finally created and imposed upon a system, they shed light on dysfunction that has long gone unnoticed. In the words of Admiral Wade, “We are just at the beginning here, but we have uncovered so many issues.”

Part 2 will focus on Firepower.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Forward…From the Sea, U.S. Department of the Navy, 1994. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/navy/forward-from-the-sea.pdf

2. Naval Studies Board, “Responding to Capability Surprise: A Strategy for U.S. Forces,” 2013. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/14672/responding-to-capability-surprise-a-strategy-for-us-naval-forces

3. Captain Dale C. Rielage, USN, “An Open Letter to the U.S. Navy from Red,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, June 2017. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2017-06/open-letter-us-navy-red

4. For more on the Millenium Challenge exercise see: Micah Zenko, “Millenium Challenge: The Real Story of a Corrupted Military Exercise and Its Legacy,” War on the Rocks, November 5, 2015. https://warontherocks.com/2015/11/millennium-challenge-the-real-story-of-a-corrupted-military-exercise-and-its-legacy/

Excerpt from official Millenium Challenge Report: “As the exercise progressed, the OPFOR free-play was eventually constrained to the point where the end state was scripted. This scripting ensured a Blue operational victory and established conditions in the exercise for transition operations.”

5. Admiral Scott Swift, “A Fleet Must Be Able to Fight,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 2018. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018-05/fleet-must-be-able-fight

6. For novelty of SMWDC reference: Vice Admiral Thomas H. Copeman III, “Tactical Paradigm Shift,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, January 2014. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-01/tactical-paradigm-shift

Excerpt:

“It may be hard to believe, but the U.S. Navy, widely recognized as the greatest Fleet the world has ever known, lacks an organization tasked with development, training, and assessment of the full scope of tactics for the warfare community on which it was founded 238 years ago—surface warfare. This is going to change.”

Rear Admiral John Wade, “Red Sea Combat Generates High Velocity Learning,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, September 2017. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2017-09/red-sea-combat-generates-high-velocity-learning

Excerpt:

“In the years preceding the establishment of the Warfighting Development Centers, the surface warfare community did not have a single organization that could cull lessons from combat and then coordinate the effort to achieve high-velocity learning not only in the fleet and school houses, but also across the engineering and acquisition communities. In June 2015, the establishment of the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) closed this gap.”

For TOPGUN analogy see: “SMWDC Surface Warfare Officers’ Top Gun (Top SWO)” from Naval Surface Force U.S. Pacific Fleet https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6PI-pmYfPI

7. Sdyney Freedberg, “Top Gun for Warships: SWATT,” Breaking Defense, January 16, 2018. https://breakingdefense.

8. Admiral Scott Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/

9. Admiral Scott Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/

Excerpt on timing: “After two years and more than six iterations, the reestablished Fleet Problem has never before been discussed in public. In that context, it is fair to ask why we decided to discuss the concept at this point.”

10. Admiral Scott Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/

11. Megan Eckstein, “Fight to Hawaii: How the U.S. Navy is Training Carrier Strike Groups for Future War,” U.S. Naval Institute News, March 22, 2018. https://news.usni.org/

12. A caveat to this is that NTC training shifted to counterinsurgency operations and remained there for several years before shifting more toward high-end/hybrid warfare around 2012-2014.

For National Training Center reference:

Colonel John D. Rosenberger, “Reaching Our Army’s Full Combat Potential in the 21st Century: Insights from the National Training Center’s Opposing Force,” Institute of Land Warfare, February 1999, https://www.ausa.org/

Major John F. Antal, “OPFOR: Prerequisite to Victory,” Institute of Land Warfare, May 1993. https://www.ausa.org/

Sydney Freedberg, “All Active Combat Brigades Trained vs. New Russian Tactics: FORSCOM,” Breaking Defense, October 17, 2017. https://breakingdefense.com/

Interesting caveat from above: ““Before, in the ’80s and ’90s, it was very rote,” Abrams said. “You would get there on this day and on Friday, you would do a road march out, and you’d get an order for an attack, and you would go attack. And then, four hours after the attack was done, you’d do an After Action Review, you’d get another order, and you’d get ready do something else. It was all very lockstep.”

Dennis Steele, “Training for Decisive Action, “Old-School without Rotations Going Back in Time,'” Army Magazine, February 2013. http://ausar-web01.inetu.net/

For Red Flag Reference:

Brian Daniel Laslie, “Red Flag: How the Rise of “Realistic Training” After Vietnam Changed the Air Force’s Way of War, 1975-1999,” http://krex.k-

414th Combat Squadron Training “Red Flag,” July 2012. https://www.nellis.af.

13. Lt. Col. Bradford T. Duplessis, “Our Readiness Problem: Brigade Combat Team Lethality,” Armor, Fall 2017. http://www.benning.army.mil/

14. Megan Eckstein, “Warfighting Development Centers, Better Virtual Tools Give Fleet Training a Boost,” U.S. Naval Institute News, February 23, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/02/

15. William S. Bradley, “The Training Mandate,” Marine Corps Gazette, October 1990. https://search.proquest.com/marinecorps/docview/206324175/fulltext/C0F8174E7BD74AAEPQ/1?accountid=48498

16. For “Die in Place” references see:

Staff, Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, “Opposing Force TTP,” Marine Corps Gazette, August 2016. https://www.mca-marines.org/

Sgt. Luke G. Cardelli, “MAGTF Integrated Exercise (MIX-16),” Marine Corps Gazette, November 2017. https://www.mca-marines.org/

17. Megan Eckstein, “Warfighting Development Centers, Better Virtual Tools Give Fleet Training a Boost,” U.S. Naval Institute News, February 23, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/02/

18. Megan Eckstein, “New Advanced Surface Navy Training Seeks to Fill Critical Gaps,” U.S. Naval Institute News, March 7, 2017. https://news.usni.org/2017/03/

19. Megan Eckstein, “With Navy Struggling to Balance Training, Maintenance, Deployment Needs, Service Looking at Data Analysis to Warn of Readiness Problems,” U.S. Naval Institute News, November 13, 2017. https://news.usni.org/2017/11/

20. Government Accountability Office, “Military Readiness: Progress and Challenges in Implementing the Navy’s Optimized Fleet Response Plan,” May 2, 2016. https://news.usni.org/wp-

21. To get an idea of certification requirements see:

Roland J. Yardley, et. Al, “Use of Simulation in Training for U.S. Surface Force,” RAND, 2003. https://www.rand.org/content/

COMNAVAIRFORINST 3500.20B, Aircraft Carrier Training and Readiness Manual, February 14, 2008, http://navybmr.com/study%

COMNAVSURFPAC/COMNAVSURFLANT INSTRUCTION 3500.11 Surface Force Exercise Manual, http://www.dcfpnavymil.org/

22. Lieutenant Jeff Vandenegel, “A Zero-Sum Game,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings Professional Notes, October 2015. https://www.usni.org/

23. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Wants More Complex Sub-on-Sub Warfare Training,” U.S. Naval Institute News, October 27, 2016. https://news.usni.org/2016/10/

24. Lieutenant Erik A.H. Sand, “Performance Over Process,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, October 2014. https://www.usni.org/

25. Office of Naval Intelligence, “The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century, 2015. https://fas.org/irp/agency/

26. Office of Naval Intelligence, “China’s Navy,” 2007. https://fas.org/irp/agency/

27. Admiral Scott Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/

28. On timing see: Admiral Scott Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/

Excerpt: “A year prior, Pacific Fleet had formed a Red team, the Pacific Naval Aggressor Team (PNAT), to support wargaming.”

For more see: Captain Dale Rielage, “Wargaming Must Get Red Right,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, January 2017. https://www.usni.org/

29. Admiral Scott Swift, “A Fleet Must Be Able to Fight,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 2018. https://www.usni.org/

30. Captain Dale Rielage, “Chinese Navy Trains and Takes Risks,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 2016. https://www.usni.org/

31. Admiral Scott Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/

32. Andrew Erickson and Ken Allen, “China’s Navy Gets a New Helmsman (Part 2) Remaining Uncertainties,” Jamestown Foundation, March 14, 2017. https://jamestown.org/program/

33. For amount of ships devoted to interwar period Fleet Problems see: Albert Nofi, To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923-1940.

Excerpt: “Virtually every one of the fleet problems involved a majority of the battleships, carriers, and destroyers in commission, and, as still considered “in commission.” Fleet Problem XI (1930) involved the fewest ships, only about 24 percent of the fleet, but came only a month after Fleet Problem X, which had involved nearly a third of the fleet; as some ships did not take part in both problems, the actual overall rate of participation was more than a third of vessels officially in commission. During the 1930s, Fleet Problems XIII (1932) through XX (1939) all involved about half or more of the fleet, peaking at 69 percent in Fleet Problem XVII (1936).”

34. Lieutenant Brendan Cordial, “Too Many SWOs Per Ship,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2017. https://www.usni.org/node/

35. To get a sense of Cold War-era exercising standards and activity see the book Oceans Ventured (2018) by Reagan-era Navy Secretary John Lehman. The book is mainly about Navy exercises in the 1980s.

36. This is in reference to decision-making on employing the ship’s weapons and sensors, how to “fight the ship.” It is not in reference to things like damage control and medical assistance in which enlisted Sailors would play a prominent role.

37. On nature of exercising realism and artificialities see: Frederick Thompson, “Did We Learn Anything from that Exercise? Could We?” Naval War College Review, July-August 1982. https://digital-commons.usnwc.

Featured Image: Pacific Ocean, NNS (April 18, 2018) Lieutenant Craig Stocker, a Warfare Tactics Instructor assigned to Surface Warfare Officer School Newport, R.I., is temporarily attached to Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) tracks and mentors crewmembers during an Anti-Submarine exercise onboard the USS Stockdale (DDG 106). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Amanda A. Hayes/released)