By Captain James P. McGrath, III, USN

The decommissioning of USS Simpson (FFG 56) in 2015 left the U.S. Navy without any frigates for the first time since 1950. Several pundits derided this “frigate gap” and suggested reclassifying the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) as a frigate to keep frigates in the inventory.1 These calls, which the U.S. Navy wisely resisted, are symptomatic of a century’s old challenge over how navies classify warships. Warship classification exists for two reasons, one practical and one political. Practically, naming a group of ships with similar characteristics allows for better comparison of capabilities within and among navies. Politically, warship classifications signal national intentions or influence political leaders who fund warship construction. While the practical reason may seem more functional, the political reason frequently determines classification.

Four common types of major surface combatants exist today: cruisers, destroyers, frigates, and corvettes. Each title has historical roots and a variety of practical and political implications. This essay explores how these classifications came to represent modern ship types, how nations abuse them to suit their needs, and how they facilitate or hamper exploration of alternative fleet designs as the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) challenges the U.S. Navy to do in A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority.2

Names, Roles, and Conventions

The classification of warships is as old as naval warfare. When historians evoke the ancient Trireme, naval scholars envision a large wooden vessel with three banks of oars and a prominent ram-style bow. During the golden age of sail, mentioning a ship-of-the-line conjured elements of national pride and a clear understanding of powerful broadsides that could only be defeated by similarly strong ships. Another commonly understood ship type during the age of sail was the frigate. Similar in length to ships-of-the-line and with comparable canvas, but significantly less broadside, frigates were swift ships, able to outrun what they could not outgun.

The rebirth of the American Navy authorized in the Naval Act of 1794 centered around a fleet of six frigates, “four ships to carry forty-four guns each, and two ships to carry thirty-six guns each,”3 conceived by Joshua Humphries and designed with the “outrun what they could not outgun” mantra in mind. Lighter and faster than ships-of-the-line, frigates often scouted for and covered the flanks of the battle line. Frigates also conducted independent operations, and several of the most famous naval actions of the late-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were frigate duels. Corvettes carried even fewer guns on the smallest hulls capable of open-ocean operations. These ships often conducted raids or served as picket ships between fleets. The relatively consistent classification of warships in this age allowed for easy comparison and provided fleet commanders insight into the type of fleet required to defeat a foe.

Warship classifications evolved to describe new types of warships developed from the new technologies of the industrial age. With the advent of steam power ships gradually improved their propulsion with paddlewheels, and later screw propellers. Initially, these new warships kept the basic shape and mission of the frigates of old, so they kept the frigate name, albeit caveated as paddlewheel or screw frigates. With the addition of armor and turreted gun mounts, titles like cruiser and battleship emerged. By the mid-1880s, the terms “ship-of-the-line” and “frigate” fell out of use. The explosion of ship types resulted in an expansion of naming conventions with little commonality between navies. These new classes of ships came to describe the changing fleet designs of this new era of naval power.

Two common and modern warship classifications, both derived from descriptions of the ship’s mission, grew from this explosion of ship types. Designed to cruise the oceans independently, cruisers filled the role held by frigates in the age of sail, but capabilities varied widely across the world’s navies. The other type, the destroyer, represented a genuinely new classification of warship. The first ship to use the term “destroyer” was the Spanish torpedo-boat destroyer Destructor commissioned in 1887. What set Destructor apart as a new class of warship was her combination of size, large enough to operate in the open sea with the battle fleet; speed, 22.6 knots made her one of the fastest ships in the world in 1888; and her armament, seven rapid firing guns, and two torpedo tubes. Over the next three decades the destroyer evolved to provide all manners of protective functions for the fleet including usurping the role of torpedo boats and proving especially effective against the submerged torpedo boat, the submarine. Development of these new ship classes harnessed the technical advances of the industrial age and drove the development of modern fleets.

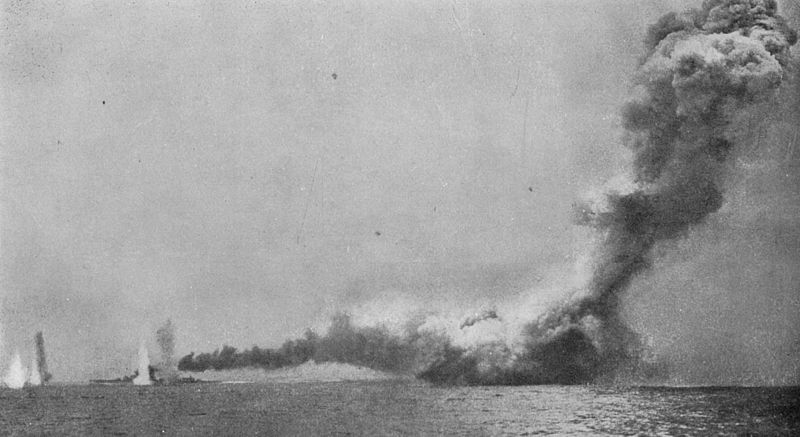

In 1906, Admiral Sir John Fisher of the Royal Navy shocked the world with the commissioning of HMS Dreadnought, a revolutionary, all-big-gun, turbine-powered battleship, which instantly made the world’s battleships obsolete. The capability gap between dreadnoughts and pre-dreadnoughts sparked a naval arms race with the world’s maritime powers scrambling to build bigger and better battleships. This naval arms race is widely considered one of the principal causes of World War I. What constitutes a dreadnought, however, remains contentious, a situation confused by sub-classifications such as super-dreadnought and semi-dreadnought making fleet comparison challenging. Even more confusing and unfortunate is the classification of the battlecruiser. One of Fisher’s goals in developing Dreadnought was to help create a class of ships capable of outrunning anything they could not outgun – a large light-cruiser – the true successor of the sailing frigate. Unfortunately, and here is where ship classification can become dangerous to fleet design, politicians insisted on calling these ships battlecruisers since they looked like battleships, similar in size and armament but deficient in armor, which the designers sacrificed for speed. This unfortunate classification led to the battlecruiser’s misemployment in the battle line, which constrained their speed advantage, and where their lack of armor made them vulnerable to large caliber gunfire. This was demonstrated catastrophically at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 when three battlecruisers exploded with incredible loss of life after only a few hits. Twenty-five years later, the last British battlecruiser, HMS Hood, met the same fate after only five salvos from the German battleship Bismarck. Classifying ships for political purposes can have deadly effects.4

Treaties and Types

After World War I, in an effort to prevent a naval arms race like the one that preceded the war, world leaders aimed to curtail warship construction by treaty. Ensuring all parties met treaty obligations required common definitions of ship types. The Five Power Treaty of 1922 and the London Naval Treaty of 1930 defined ship classes in a manner agreed upon by all signatories. The first treaty defined capital ships as those displacing more than 10,000 tons and carrying guns greater than 8-inches.5 Seeking an alternative to the now constrained battle line, Japan designed and built a series of cruisers right to these limits in the 1920s. These highly-capable warships caused great concern in the United States and Great Britain over the gap in cruiser capability. The London Naval Treaty, an attempt to further and more broadly restrict naval construction, especially of these “heavy” cruisers, defined lesser warship classes as follows:

Cruisers:

Surface vessels of war, other than capital ships or aircraft carriers, the standard displacement of which exceeds 1,850 tons (1,880 metric tons), or with a gun above 5.1 inch (130 mm.) calibre.

The cruiser category is divided into two sub-categories, as follows:

(a) cruisers carrying a gun above 6.1-inch (155 mm.) calibre;

(b) cruisers carrying a gun not above 6.1-inch (155 mm.) calibre.

Destroyers:

Surface vessels of war the standard displacement of which does not exceed 1,850 tons (1,880 metric tons), and with a gun not above 5.1-inch (130 mm.) calibre.6

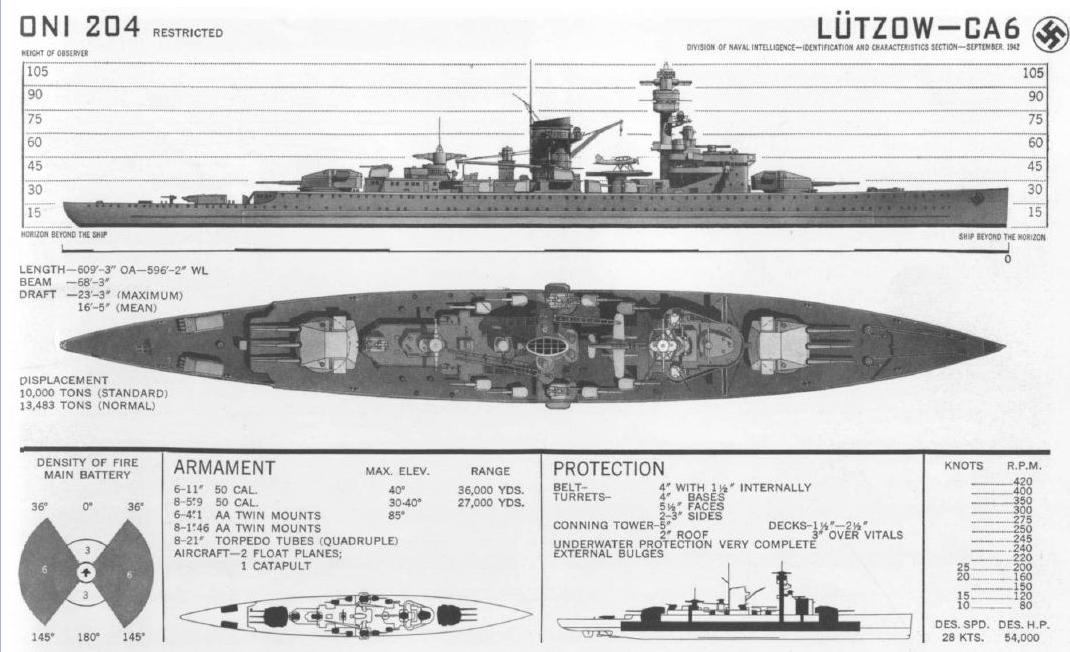

By 1930, there existed a shared understanding of capital ships (BB), aircraft carriers (CV), heavy cruisers (CA), light cruisers (CL), and destroyers (DD), but that shared understanding quickly fell apart since not every nation building warships was party to the treaty. The re-building German Kriegsmarine, governed by the Treaty of Versailles and not the Washington Treaty system, built three 14,520 ton, 11-inch gun Deutschland-class ships in the early 1930s. Although capital ships under the terms of the Washington Treaty, the Germans initially called them Panzerschiffe (armored ships) and later classified them as heavy cruisers. The British press derisively dubbed them “pocket battleships” since the Panzerschiffe were significantly smaller than most other nations’ capital ships further confusing what type these ships actually were.

The collapse of the Washington Treaty system in 1936 removed the constraints on warship classification, but the nomenclature initially remained as nations prepared for war. During World War II, the belligerent navies significantly expanded in size, creating a vast array of ship types not envisioned in 1922 or 1930. To describe these new ships, navies returned to the pre-World War I practice of naming them as they saw fit. The British brought back the historical terms corvette and frigate to describe dedicated anti-submarine vessels designed for convoy escort. The Flower-class corvettes fit well with the sailing vessel definition as the smallest class of ocean-going vessels capable of independent operations. The British River-class began as a twin-screw corvette, but in 1941 was reclassified as a frigate. While the frigate rated above the corvette in the age of sail, this new class of ship bore no resemblance to the prestige and importance of sailing frigates.7 The Americans chose the title destroyer escort (DE) for their version of the vessel filling the open-ocean escort role, but they also employed a class of patrol frigates (PF), the Tacoma-class, built to a modified River-class design. The United States produced 96 Tacoma-class PFs between 1943 and 1945, 20 of which served in the Royal Navy. The U.S. Navy considered these vessels inferior to the indigenously designed DEs, so kept the frigate classification to differentiate them. By the end of World War II, the modern classifications of cruiser, destroyer, frigate, and corvette appeared firmly established, although at the time the application of these classifications lacked continuity among the Allied navies. The outlier was the newly designed and named destroyer escort possessed only by the Americans, faster, more maneuverable and better-armed than the frigates but less capable than the destroyer.

Warships in the Guided Missile Age

The advent of the missile age further upset the Washington Treaty system of warship classification as nations began developing new missile-armed platforms for fleet anti-aircraft defense. The Navy’s missile-firing surface combatants (marked by a “G” in their classification from their guided missiles) were first born from World War II-era heavy and light cruisers that had their main armaments converted from large caliber guns into missile batteries. These ships kept their base cruiser designations (CAG/CLG and later CG). But lacking a clear classification example for the new warships built around missile batteries instead of guns, the U.S. Navy initially applied ship classifications it already had. It designated larger missile ships destroyer leaders (DLG), medium-sized missile ships derived from destroyer designs remained destroyers (DDG), and ships derived from smaller destroyer escorts kept that classification (DEG).8 But politics is tricky and explaining to Congress the difference between a destroyer leader, a destroyer, and a destroyer escort, and why the Navy needed all three, became a challenge. The Navy solved the image problem by evoking the prestige of the age-old title of frigate for the larger missile ships. Thus, the destroyer leader became a frigate (although kept the DL hull designation) in 1950, to make building and funding them more politically palatable.

Two problems arose due to the American system. First, it ran counter to the rest of the world’s ship classification system, especially NATO’s. In NATO, the primary surface combatants were cruisers (which were quickly disappearing), destroyers, frigates (the small open-ocean escort version), and corvettes. The second reason is another example of politics driving ship classification. With the singular exception of USS Long Beach (CGN 9), America built no “traditional” cruisers after 1949, and by the mid-1970s most of the converted World War II-era cruisers had reached the end of their useful service. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a resurgent Soviet Navy built a number of ships it classified as cruisers, leading to an apparent “cruiser gap” of 19 Soviet cruisers to America’s six. That the American frigates outclassed the Russian cruisers mattered little to policymakers worried about fighting the Cold War. So in 1975, the United States reorganized its ship classifications with frigates reclassified as cruisers (CG), destroyers remaining destroyers (DD/DDG), and destroyer escorts becoming frigates (FF/FFG).9 Additionally, the Navy reclassified the Oliver Hazard Perry-class patrol frigate (PFG), then under construction, as a frigate (FFG). This reorganization also aligned U.S. warship classifications with its NATO allies, simplifying allied ship employment and doctrine.

The 1975 reorganization did not end the confusion over ship classifications. That same year, the first Spruance-class ship joined the fleet. Displacing over 8,000 tons, these ships equaled the size of the newly re-designated cruisers but lacked the robust anti-air capability. Since the U.S. Navy committed the cruiser designation to large anti-air ships, these new ships were classified as destroyers.10 Later that decade, the newly-developed Aegis weapons system was installed on the Spruance-class hull to create a highly capable anti-air warfare ship. Despite displacing only slightly more than the Spruance-class, the new Ticonderoga-class ships earned the designation of cruiser. The Navy’s rationale included the ship’s anti-air mission and the inclusion of command spaces suitable for flag officers to control fleets in battle.11

Classification and Politics

The United States is not alone in the questionable classification of ships. The Soviets designated the Kiev-class as heavy aviation cruisers, even though they operate fixed-wing aircraft and look like aircraft carriers. The cruiser designation allows the 45,000-ton ships to pass through the Turkish Straights in compliance with the 1936 Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Straits. The convention permits capital ships of Black Sea powers including Russia to transit the straights but excludes aircraft carriers. Fortunately for the Russians, the 1936 definition of aircraft carrier determines straight transit eligibility:

“Aircraft-Carriers are surface vessels of war, whatever their displacement, designed or adapted primarily for the purpose of carrying and operating aircraft at sea. The fitting of a landing on or flying off deck on any vessel of war, provided such vessel has not been designed or adapted primarily for the purpose of carrying and operating aircraft at sea, [emphasis added] shall not cause any vessel so fitted to be classified in the category of aircraft-carriers. ”12

By accepting the vessel as a cruiser whose primary purpose is not “carrying and operating aircraft at sea,” Turkey allows Kiev-class ships to transit the straights. Russia uses the same classification for the Kuznetsov-class, even though China classifies its Kuznetsov-class ship, Liaoning, as an aircraft carrier.

Classifying ships to skirt international convention is not the only reason to downplay a ship’s capabilities. Article 9 of the Japanese constitution prevents the nation from maintaining an offensive military capability.13 In the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force that equates to limiting ship types to destroyers or smaller, ostensibly since those types serve defensive roles. Within the last decade, Japan built four “helicopter destroyers (DDH)” which look suspiciously like aircraft carriers with full-length flight decks. The newest, the Izumo-class, can operate the fixed-wing, short take-off, vertical landing (STVOL) F-35B Lightning II. Despite recent reinterpretations of the Japanese constitution allowing the use of its military to defend allies in the event of an attack, calling these ships destroyers enabled the Japanese Diet to justify funding them as defensive.14

The German Baden-Württemberg-class (7200 tons) and Spanish Álvaro de Bazán-class (6300 tons) frigates both displace more than the destroyers they replaced, are only slightly smaller than contemporary destroyers, and are similarly armed with high-tech anti-air, anti-submarine, and anti-surface sensors and weapons.15 Both the Deutsche Marine and the Armada Española emphasize the defensive roles of their naval forces, and building frigates is politically more palatable than building destroyers, even though these frigates are essentially equivalent to the destroyers of peer navies.16

The United States continued its Cold War tradition of confusing the world, and itself, with ship classifications with the development of the LCS. As then-Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus noted, “When I hear L, I think amphib, and it’s not an amphib. And I have to spend a good deal of my time explaining what littoral is.”17 Mabus even directed reclassifying LCS as a frigate, but the reclassification never came to fruition, partly because the LCS is significantly less capable than the world’s other frigates. Weighing in between 3100 and 3500 tons, armed with a 57mm gun, and with no real long-range anti-air capability, LCS more closely aligns with modern corvette classes than the frigates. But the United States does not want corvettes, because they are viewed as too small for its blue-water mentality.

The other oddly classified ship is the Zumwalt-class destroyer. Displacing over 14,000 tons, USS Zumwalt (DDG 1000) weighs as much as a World War II Baltimore-class heavy cruiser. Armed with 6.1 inch (155mm) guns, she meets the Washington Treaty system armament criteria for a light cruiser. She is also significantly larger than the Ticonderoga-class cruisers.18 Yet Zumwalt remains classified as a destroyer, again for political reasons. Derived from the “Destroyer for the 21st century (DD-21)” program of the early 1990s, the Navy continued to call this ship a destroyer even as it grew in size and complexity. When the U.S. Congress eventually authorized and funded the building of “a destroyer,” Zumwalt kept that classification.19

In the mid-1990s, the U.S. Navy instituted a program called Surface Combatant for the 21st Century (SC-21). Designed to address the lack of land attack and fire support capability in the surface fleet, the program looked to develop a family of ships that would not necessarily fall in line with the traditional ship classes.20 Despite recognizing the potential for new ship classes, the U.S. Navy continued to shoehorn modern warships into the traditional ship classes until the development of LCS in the early 2000s. As mentioned above, LCS did not fit nicely into traditional categories, and its classification brought about more confusion than clarity.

Today’s U.S. ship designers also eschew the traditional ship classes. To meet the CNO’s goal “To better meet today’s force demands, [and] explore alternative fleet designs, including kinetic and non-kinetic payloads and both manned and unmanned systems,”21 the Navy’s Future Surface Combatant (FSC) program envisions three ship classes – Large Surface Combatant, Medium Surface Combatant, and an Unmanned Surface Combatant – to replace the current fleet of cruisers, destroyers, and the already retired frigates.

The Enduring Classification Gap

Today’s U.S. Navy still continues the century-old tradition of conforming ship classifications to more political instead of practical requirements. While it might appear trivial what a ship is called, ship classifications bring with them expectations such as armament and mission that may not match the practical needs of the fleet. The resultant ship tends to cost more and take on different missions than fleet designers initially intended in order to justify the higher price tag. Additionally, conforming to existing ship classification conventions limits the ability to develop ship classes necessary for exploration of alternative fleet designs. By naming its newest ship class “FFG(X)”, the U.S. Navy provides another illustration that while the classification of ships serves two purposes, political and practical, the political purpose usually wins.

Captain McGrath is a nuclear-trained surface warfare officer who commnded Maritime Expeditionary Security Squadron Seven in Guam. After staff tours at Seventh Fleet, Naval Forces Europe, and the Joint Staff J7, he currently serves as a military professor of Joint Military Operations at the Naval War College in Newport, RI. These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the official position of any U.S. government department or agency.

References

1. Christopher P. Cavas, “LCS Now Officially Called a Frigate,” Defense News, 15 January 2015, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2015/01/15/lcs-now-officially-called-a-frigate/

2. John Richardson, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority: Version 1.0 (Washington, DC, Officer of the Chief of Naval Operations, 2016), 6.

3. Naval Act of 1794, Session 1, Chapter XII, 3rd Congress (1794).

4. Philip Sims, Michael Bosworth, Chris Cable and Howard Fireman, Historical Review of Cruiser Characteristics, Roles and Missions: SFAC Report Number 9030-04-C1 (Washington, DC, Naval Sea Systems Command, March 28, 2005, http://navalmarinearchive.com/research/cruisers/cr_navsea.html

5. Limitation of Naval Armament (Five Power Treaty or Washington Treaty), 43 Stat. 1655; Treaty Series 671, Article XI & XII.

6. Limitation and Reduction Of Naval Armament (London Naval Treaty), 46 Stat. 2858; Treaty Series 830, Article 15.

7. Sims, Bosworth, Cable and Fireman, Cruiser Characteristics, Roles and Missions.

8. Andrew Toppan, “The 1975 Reclassification of US Cruisers, Frigates and Ocean Escorts,” Haze Gray and Underway, March 30, 2000, http://www.hazegray.org/faq/smn6.htm#F4

9. Andrew Toppan, “The 1975 Reclassification of US Cruisers, Frigates and Ocean Escorts,” Haze Gray and Underway, March 30, 2000, http://www.hazegray.org/faq/smn6.htm#F4

10. David W. McComb, “Spruance Class,” Destroyer History Foundation, Accessed 21 June, 2018http://destroyerhistory.org/coldwar/spruanceclass/

11. Sims, Bosworth, Cable and Fireman, Cruiser Characteristics, Roles and Missions.

12. 1936 Convention Regarding the Regime of the Straits, Adopted in Montreux, Switzerland on 20 July 1936, Annex II, Section B.

13. The Constitution of Japan, Chapter II, Article 9, May 3, 1947. https://japan.kantei.go.jp/constitution_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html

14. Linda Sieg and Kiyoshi Takenaka, “Japan Takes Historic Step from Post-War Pacifism, OKs Fighting For Allies,” Reuters, June 30, 2014.

15. Contemporary destroyer tonnages: Russian Sovremennyy-class (6600 tons), Japanese Kongō-class (7500 tons), Chinese Type 052D (7500 tons), British Type 45 (8500 tons), and American Arleigh Burke-class (9600 tons).

16. Deutsche Marine official website http://www.marine.de/; Armada Española official website, http://www.armada.med.es/

17. Cavas, “LCS Now Officially Called a Frigate,”

18. Even though Zumwalt’s guns are effectively useless with the cancellation of the Long Range Land Attack Projectile (LRLAP), but the guns are still mounted and available if projectiles are procured.

19. Sims, Bosworth, Cable and Fireman, Cruiser Characteristics, Roles and Missions.

20. Norman Friedman, U.S. Destroyers: An Illustrated Design History (Annapolis, MD, Naval Institute Press, 2004), 434-5.

21. Richardson, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, 6.

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (December 8, 2016) The Navy’s most technologically advanced surface ship USS Zumwalt (DDG 1000) steams in formation with USS Independence (LCS 2) and USS Bunker Hill (CG 52) on the final leg of her three-month journey to her new homeport in San Diego. (U.S. Navy Combat Camera photo by Petty Officer 1st Class Ace Rheaume/Released)