Notes to the New CNO Topic Week

By Commander Rob Brodie, USN

Restoring authority and accountability will quickly solve the most pressing of our material, personnel, and joint/combined operational issues and inculcate a culture of innovation. The cause of the Fitzgerald and McCain collisions was the administrative chain of command’s decisions to send untrained officers to the fleet while also replacing intuitive with non-intuitive ship control consoles without training support. But instead, only the operational chain of command was held accountable for the loss of life. We ask mostly administrative regional commanders without operational forces, the appropriate skillsets, or adequate manning, such as Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Japan, to lead the development of operational plans and exercises with high-end foreign forces who normally operate with operational commanders. This results in confusion and extra effort for our allies. We should take advantage of the significant shortage of staff officers, LCDRs, CDRs and CAPTs, to cull the excessive administrative and operational bureaucracy and create the dynamic, learning organization we claim to be.

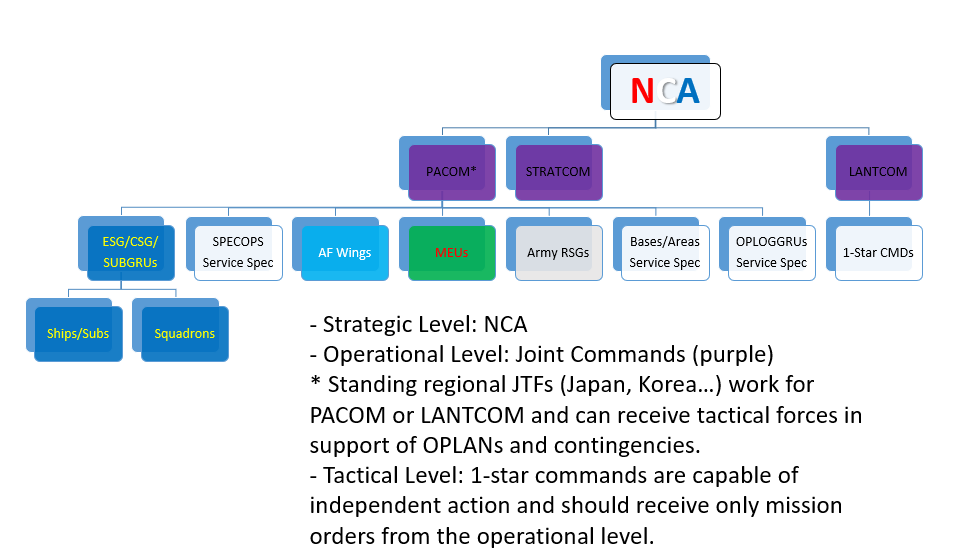

In the early 2000s, in order to facilitate a rapid decision cycle and maneuver warfare coordination, we were supposed to refocus our tactical forces around combined arms one-star commands, Navy carrier and submarine strike groups, Navy/Marine Corps expeditionary strike groups, Army brigade combat teams, and Air Force expeditionary air wings. Unfortunately, the echelons above see themselves as tactical backstops instead of operational forward thinkers, leading to a focus on building, staffing, and certifying maritime operations centers for every layer instead of sound operational thinking and planning. And do we really need all those naval layers if our total deployable force is only a couple carrier and expeditionary strike groups from each coast?

Even at the joint level, the Air Force and Army aren’t going to add significantly greater numbers of similar formations, especially if there are no established and friendly ports or airfields where they can deploy. Pacific and Atlantic joint operational commands with service components to maintain the tactical forces, using the help of regional combined forces coordination centers like the Combined Forces Headquarters in Korea to do the local warfighting, should be able to operate our forces and provide inputs to the strategic level. Modernization and maintenance ideas would bubble up from the tactical level during annual lessons learned and trade shows on each coast, appropriately staggered to cross-pollinate the feedback loop.

Learning is only a process if there is a feedback loop. The numerous operational and administrative layers we currently have make it almost impossible for something learned at the tactical level or dreamed by industry or academia to make it not only to production, but be operationalized in the fleet in time and at a price to provide the required return on investment.

The lag between idea and capability has already demotivated many in my generation, which grew up fishing, reading, working, and making our own entertainment. Those raised in newer generations accustomed to instant gratification will not and should not tolerate the sluggish status quo, especially when we have the opportunity to rapidly fix our processes by massively cutting a bureaucracy we already can’t staff.

Featured Image: SAN DIEGO (Aug. 29, 2019) Boatswain’s Mate 3rd Class Alex Olivera, from Brockton, Mass., inspects an anchor chain on a barge next to the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Olympia O. McCoy)