By Walker D. Mills

The world is increasingly urban and littoral. This convergence between urbanization and the littoral, or littoralization, can lead to “the worst of both worlds” and may remake the littorals into hotspots of instability and conflict. At the same time, the U.S. Marine Corps is shifting its focus away from decades of counterinsurgency and irregular warfare in the Middle East. In 2017, the Marine Corps published a new operating concept focused on the littorals called Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment (LOCE). LOCE emphasized “fighting for and gaining sea control, to include employing sea-based and land-based Marine Corps capabilities to support the sea control fight,” but at the same time cautioned that “major combat operations (MCO) and campaigns versus peer competitors are beyond the scope of this concept.” A more recent and still not publicly released operating concept, Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO), expanded on LOCE to cover major combat operations and campaigns against a peer competitor – most likely China.

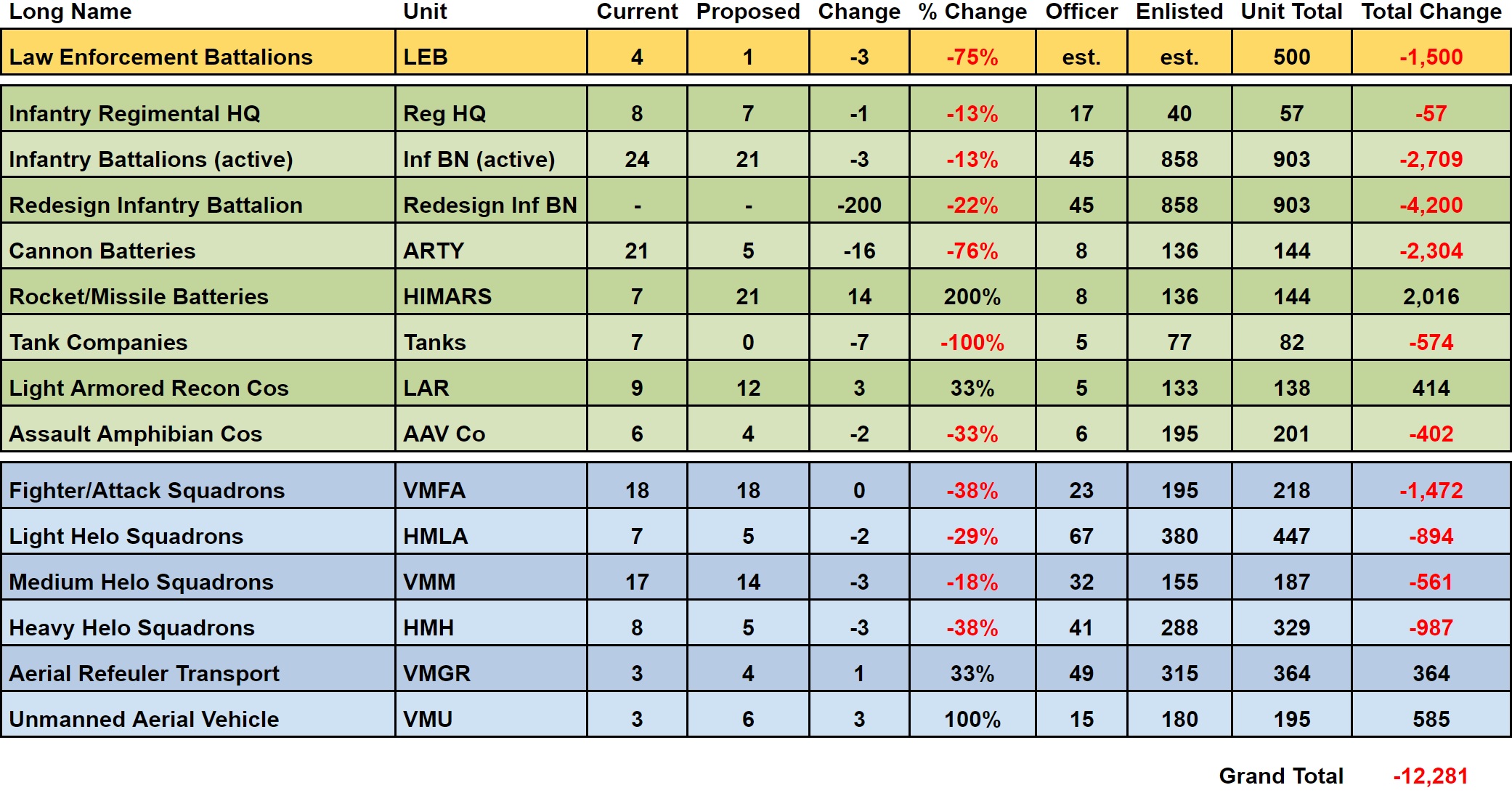

EABO and a growing focus on great power competition promises to be the future of the Marine Corps and is the basis for the new Commandant’s Force Design 2030 effort. The Commandant of the Marine Corps has asserted that the Corps is “the preeminent littoral warfare and expeditionary warfare service.” And littorals are unquestioningly where the Marine Corps is most needed and can be the most effective. But this pivot to the littoral does not necessarily mean the Marine Corps can leave irregular warfare and lower-intensity conflicts behind. History and current trends make clear the global littorals are a haven of irregular warfare, and always have been for millennia.

In a recent interview the Marine Commandant expressed his view that a force optimized for major combat operations against a highly capable adversary can easily adapt to operate effectively across the range of military operations:

“We’re building a force that, in terms of capability, is matched up against a high-end capability. The premise is that if you do that, if you build that kind of a force, then you can use that force anywhere in the world, in any scenario; you can adapt it.”

He cautioned, “But the inverse is not true.” The Commandant is correct, a well-trained and highly capable force can adapt to new threats. But the question is how long does that take? The U.S. experience in Iraq and Afghanistan shows that adapting to a low-end fight can take years, including changes to strategy, acquiring the right equipment, and writing and training to the relevant doctrine. Clearly the Marine Corps needs to prioritize and adapt to meet the challenges posed by China, a highly capable competitor and potential adversary. However, as the Marine Corps looks beyond the irregular threats of the Middle East, it cannot afford to abandon those hard-won lessons. Irregular warfare and asymmetric threats can and likely will follow the Marine Corps to the littorals. In many cases, they are already there.

Irregular Warfare in the Littorals

The threat of non-state actors and irregular warfare in the littorals is not new. Even the rebellious 13 American colonies leveraged maritime irregular warfare to support their bid for independence, employing a mix of littoral raiding forces and state-sponsored privateers to target British shipping at sea and in their home waters. Criminal and entrepreneurial activity has deep roots at sea with a long history of pirates taking vessels and raiding lucrative targets ashore. This type of amphibious raiding has taken place in nearly every global littoral region at some time or other. Some of the earliest recorded history is accounts of “the Sea Peoples” attacking the Egyptian kingdom of Ramesses II in the Bronze Age. In 793 AD, Vikings from Scandinavia raided the monastery at Lindisfarne, kicking off the Viking Age. Piracy was rampant in the colonial Caribbean, both by pirates operating independently and by privateers, which were pirates operating as proxies with the official sanction of European kingdoms to raid vessels and settlements.

Today pirates continue to operate. They concentrate their operations in the littorals and near international chokepoints such as the Gulf of Guinea and the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, often taking advantage of the seams between different law enforcement regimes ashore and offshore. Pirates operating from bases in Somalia became famous after they hijacked the Maersk Alabama, and where the subsequent rescue operation by the U.S. Navy SEALs was made into the blockbuster Captain Phillips.

But pirates are now more prevalent elsewhere, especially in the Asian littoral. A plurality of total piracy now occurs in the Straits of Malacca and near Singapore. The Bay of Bengal is another piracy hotspot. The threat of piracy has also fueled the rise of a dark economy of mercenaries for hire that live and work in the littorals on commercial ships and floating armories, a potential spark for even more instability.

Effective counterpiracy efforts require a naval force supplemented with the capability to conduct visit, board, search, and seizure (VBSS) operations as well as operations against pirate bases ashore. It requires a force comfortable operating on land, at sea, and in the spaces in between. It is exactly the type of operations that Marines need to be prepared for as they shift their focus to the littorals.

Mines

Mines have long been a critical weapon in irregular warfare, whether military-grade or improvised. Sea mines – especially when deployed in maritime straits or chokepoints – are highly effective weapons and are inexpensive. During the Korean War, mines were deployed to block the approach to Wonsan Harbor by rolling them off the back of local fishing boats. Despite this crude method of employment, they were effective in sinking multiple U.S. warships. Sea mines have also notably accounted for 14 of the 18 U.S. warships damaged or sunk by hostile action since the end of the Second World War and “over the last 125 years mines have damaged or sunk more ships than all other weapon systems combined.” They were responsible for damaging three U.S. warships during the Tanker War in the Persian Gulf despite American awareness of the mine threat.

Last year, a spate of limpet mine attacks proved that mines are not just weapons of the past. Video footage indicates these attacks were perpetrated by Iran, which has not admitted responsibility. In South America, authorities have found hidden packages of drugs attached to cargo ships or hidden in secret underwater compartments, indicating that the expertise needed to place a limpet mine is not limited to the Persian Gulf.

Sea mines are yet another threat to the security of U.S. and allied vessels in the littorals that the Marine Corps may find itself dealing with. In his 2019 Planning Guidance, the Commandant of the Marine Corps mused whether or not it would be “prudent to absorb” some traditionally naval functions like mine countermeasures. It is even easier to imagine Marines being charged with raiding networks engaged in the manufacture and employment of sea mines, much like how they operated against insurgent bombmakers in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Improvised Explosive Attacks

Improvised anti-ship weapons are also a threat to U.S. and allied naval vessels and merchant shipping. In the 1990s, the Tamil Sea Tigers, the naval arm of an insurgent group in Sri Lanka, made a staple out of vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) attacks at sea. They attacked dozens of international vessels in the waters around Sri Lanka with a range of tactics. Not even warships are immune to this type of attack. In 2000, Al-Qaeda attacked the USS Cole in a suicide attack with a speedboat packed with explosives, killing 17 sailors. Captain Wayne Hughes (ret.) had also argued that ships in port are increasingly vulnerable to attack.

Ships and maritime infrastructure itself can even be repurposed as a weapon. While there is no evidence that the recent explosion in Beirut was intentional, it revealed a critical vulnerability in port security. In his 2006 novel, The Afghan, Frederick Forsyth imagined a crew of terrorists seizing a liquid natural gas (LNG) tanker to use as a massive suicide bomb. Used in such a way, a hijacked LNG tanker would have explosive power similar to a small nuclear warhead. But an oil tanker or even a stationary drilling platform could still unleash an environmental and economic catastrophe if it was damaged or sunk. The 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill released nearly 11 million barrels of oil and ultimately affected over a thousand miles of coastline. The disaster cost Exxon nearly $7 billion. Recent reports of dozens of full and stationary oil tankers anchored off the U.S. coast present a significant economic and environmental vulnerability to any group willing to take advantage of it. Today, a crippled tanker full of crude rides at anchor off the coast of rebel-controlled Yemen where it is a potential target and ecological disaster waiting to happen.

Marines have already helped to protect U.S. warships from VBIEDs by strapping light-armored vehicles with 25 millimeter cannons to the deck of the USS Boxer, an amphibious assault ship. This innovative yet extremely inefficient point defense solution may foreshadow how Marines may be forced to apply high-end capabilities like light armored reconnaissance assets to address irregular maritime threats. Marines may soon find themselves required to habitually defend fixed installations and ships at sea against attack with makeshift solutions.

Maritime Infiltration

The perpetrators of the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai that killed or injured several hundred people arrived by sea. The attackers traveled from Pakistan to Mumbai via container ship and a hijacked fishing trawler before infiltrating Mumbai on inflatable boats. The attackers demonstrated that the littoral zone could be used as a maneuver space to reach vulnerable targets.

Semi-submersible vessels, often dubbed “narco submarines,” have become a key means of transporting cocaine out of South America for drug cartels and pose a persistent problem for drug enforcement agencies. Most of the narcosubs leave from the Pacific coast of Colombia or Ecuador and are bound for Mexico, where their cargoes will often be transshipped to the U.S. overland. These vessels are often built deep in the jungle and once at sea can be incredibly difficult to locate. Analysts estimate that as much as 80 percent of Colombia’s cocaine leaves the country by sea. Fully submersible vessels have been found with dimensions up to 100-feet long and capable of carrying nine tons of cocaine from Colombia to Mexico in a single trip. Started in Colombia, the trend has now globalized and narco-submarines are now being used to infiltrate Europe. It should not be a surprise in the future if these improvised, but increasingly sophisticated and capable vessels are eventually used to smuggle terrorists, weapons, or explosives, or are employed as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices.

Conclusion

It is clear the littorals will continue to provide opportunities for terrorists and non-state actors to threaten the United States and its allies. Yet the post-9/11 fight against terrorism and other security initiatives have largely ignored the maritime space. A recent report by Stable Seas found that while “Global powers have spent billions over the last few decades in the fight against [violent non-state actors]…[they] have mostly overlooked their activities in the maritime domain” and argues that an effective approach to maritime security has to integrate onshore and offshore operations – an ideal role for the U.S. Marine Corps.

Simple yet effective weapons and tactics will continue to be a threat, and these groups may also acquire more advanced weaponry like the anti-ship missiles that have been employed by the Houthis and Hezbollah. Technological innovation and proliferation will allow land-based groups to continue threatening high-value targets at sea like cruise ships, tankers, offshore platforms, and naval vessels and especially in key straits, maritime chokepoints, and ports. At the same time, low-tech and improvised threats will remain, like narco-submarines and explosive-laden speedboats. Capt. Hughes argued in Fleet Tactics: “Often the second best weapon performs better because the enemy, at great cost in offensive effectiveness, takes extraordinary measures to survive the best weapon.”

As the Navy and Marine Corps increasingly focus on the threat from high-end weapons like Chinese supersonic anti-ship missiles and the DF-26 “Carrier Killer” ballistic missile they cannot forget about the low-end threats and “second best weapons.” The Marine Corps’ own concept for using small units, distributed among key maritime terrain to hold ocean-going targets at risk, is proof that non-state actors and rogue states may be able to do the same and achieve outsized effects because of the unique vulnerabilities and tactical geography presented by the littorals.

The Marine Corps needs to be fully cognizant of not just the potential for high-end, major combat operations in the littorals, but also of the irregular threats it may be called to address at any time. The Marine Corps needs to make sure that as it shifts its focus to major combat operations against a peer or near-peer adversary it maintains the capability to counter irregular and asymmetric threats against U.S. interests and allied in the littorals.

Walker D. Mills is a Marine Corps infantry officer currently serving as an exchange instructor at the Colombian naval academy in Cartagena.

Featured Image: STRAIT OF HORMUZ (Aug. 12, 2019) An AH-1Z Viper attached to Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron (VMM) 163 (Reinforced), 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) prepares for take-off during a strait transit aboard the amphibious assault ship USS Boxer (LHD 4). (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Dalton S. Swanbeck/Released)