1980s Maritime Strategy Series

By Joe Petrucelli

CIMSEC discussed the development of the 1980s Maritime Strategy and the role played by the CNO Strategic Studies Group (SSG) with Dr. John Hanley. Dr. Hanley served as a core member of the SSG during the 1980s and 1990s. In this discussion, he provides unique insights into the changes brought about by the strategy, the organizations and factors that contributed to its development, what made the SSG effective, and what lessons the strategy and the SSG have for the modern era.

What was new about the Maritime Strategy and how was it a shift from 1970s concepts and plans?

The Navy’s strategy in the 1970s was essentially an extension of operations in the Atlantic from World War II. Supreme Allied Commander Europe’s (SACEUR) war plans called for delivering 10 Army divisions to Europe in 10 days. Most senior Navy officers and strategists envisioned the Soviet Navy conducting a submarine campaign against our convoys delivering troops and material to Europe the way the Germans had in WWII. For example, CNO Elmo Zumwalt developed FFG-7 frigates as an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) escort force, and President Carter’s Presidential Review Memorandum 10 called for swinging the Pacific Fleet to the Atlantic.

As a submariner, I was familiar with our war plans and the exercises that we conducted to develop tactics and technology for countering the Soviet Navy. The focus of the effort in the Atlantic was to stop Soviet submarines from penetrating the GI-UK gap.

At that time, General Bernie Rogers, SACEUR, was on the record stating that he would have to begin using tactical nuclear weapons after about three days of combat. We knew that the Soviets paid close attention to the “correlation of nuclear forces” and to “combat stability” for their naval forces. We also had intelligence that much of their navy would be tasked to defend their nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) with long-range missiles in bastions in the Arctic, Sea of Okhotsk, and elsewhere, and against carrier and B-52 attacks against Russia itself.

During visits to the regional commanders-in-chief (CINCs) the SSG found that the war plans for each region were on different timelines. The SSG believed that attacking the Soviets in their Northern (Barents, Greenland Seas), Southern (Mediterranean), and Far East (Pacific) theaters of military operation simultaneously would limit the forces the Soviets could devote to the “Central Front,” creating arguments for delaying SACEUR’s initiation of the use of nuclear weapons, and that sinking their SSBNs would affect Soviet calculations, therefore raising the threshold for their use of nuclear weapons.

The strategy called for U.S. submarines and ASW forces to deploy rapidly and engage the Soviets in the heart of their operating areas, while establishing air control over and holding areas like northern Norway, Thrace, and Hokkaido as bases for strikes against Soviet Naval Air, which would allow the carrier battle groups to prudently operate within range of Soviet air bases and support ground operations. This Maritime Strategy was a strategy for employing combined and joint forces to control maritime theaters that could have a decisive effect on the outcome of the war, and not just delivering the U.S. Army and supplies to Europe.

What was your personal involvement in the strategy development process, focusing on the SSG and the Maritime Strategy?

I was a reserve submarine officer with the submarine development squadron that scheduled, designed, collected data, reconstructed, and analyzed submarine exercises, as well as data from real-world operations. In my civilian job, I spent the majority of my time doing the same kind of work for fleet exercises around the world for submarines in support of carrier battle groups. This work provided a lot of operational data supporting the design of tactics, technology, and effects of command-and-control schemes.

For my two weeks of active-duty training in 1982, I was looking for something interesting to do. A submariner friend at the Naval War College told me of this new Strategic Studies Group that was looking for some analytical help. I signed up and spent two weeks sharing an office with then Captain-selects Bill Owens and Art Cebrowski. The first task they gave me was to lay out a timeline for deployment of the Soviet Northern Fleet using some intelligence data that had recently become available, and then lay out a scheme (using actual war plan features) for deploying our Atlantic submarine force, using readiness data for both forces. We then worked on an engagement scheme that submariner Bill Owens, working with maritime patrol air (MPA) pilot Captain Dan Wolkensdorfer, called combined-arms ASW.

Extant plans had our submarine, surface, and air ASW forces (we had recently retired the ASW carriers) operating independently in deconflicted areas, mostly to defend against Soviet submarines deploying to the Atlantic. Our scheme called for blanketing the areas north of the GI-UK gap with submarines. The first priority for our submarines in their patrol areas was to sink the Soviet Navy anti-air warfare (AAW) ships to begin peeling back the onion of Soviet defenses using asymmetric advantages. This would allow P-3s to press further north and serve effectively as standoff weapons for submarines, both saving submarine torpedoes and reducing our submarine losses, which would increase our detection and attack rates of Soviet submarines. We also discovered that these AAW ships were outer air defenses that may have interfered with B-52 strikes, as our B-52s refueled over the Barents on their way to Russia. This scheme required sharing surveillance information and was the beginning of Owen’s systems-of-systems concepts.

The final day of my two-week duty, Bill Owens and Hon. Robert J. Murray (Center for Naval Warfare Studies dean and CNO SSG director) invited me to lunch and asked if I could stay. I arranged to do so.

Having laid out the operational concept, my job was to do the sea control/ASW analysis to depict timelines for Soviet SSBN losses, as well as losses to both fleets, comparing independent to combined arms ASW approaches. Art Cebrowski had the lead for the campaign analysis for air control and holding northern Norway. The data from fleet exercises was very helpful. Next, I prepared a brief for an upcoming wargame, and later prepared a brief for Owens and Cebrowski to present to the Navy leadership and to a Navy CINC’s conference. I wrote SSG I’s final report using the briefing, some additional research, and notes provided by Owens and Cebrowski.

Where Owens and Cebrowski had done detailed analysis for the Soviet Northern theater, SSG II formed two teams to do a similar level of detailed analysis for the Soviet Southern and Far East theaters. I assisted in the analysis, and for laying out a similar approach for the Pacific. Later, I worked with COMSUBLANT to change their war plans and prepare a briefing for them to use on the changes in the war plan.

The SSG is often cited as a key (if not the key) driver behind the emergence of the Maritime Strategy. But at the same time, other initiatives and groups, including exercises such as Ocean Venture ’81, the OP-603 strategist community, the Advanced Technology Panel, and Secretary Lehman’s personal involvement, were combined with pre-SSG elements such as Sea Plan 2000 and the Global War Games. In your opinion, which of these elements were the most significant and how did they interact with each other to create what we know as the Maritime Strategy?

As Peter Swartz rightly points out, the Navy would have had a Maritime Strategy without the CNO SSG. However, the details would have been quite a bit different and the OPNAV strategy may have had less effect on war plans. OPNAV was focused on programming and promoting the Navy, but the fleets and submarine force did their own planning.

As CINCPACFLT, Admiral Tom Hayward had developed his Sea Strike concept for attacking the Soviet Far East and strongly opposed “swinging” the Pacific Fleet to the Atlantic, noting that the battles may be decided by the time the fleet arrived. Others like Bing West had SECNAV Graham Claytor’s ear on pressing the Navy forward into the Norwegian Sea, which John Lehman fully supported. This started a debate over how to employ the Navy before Hayward and Murray created the SSG in 1981, with many senior admirals resisting the idea.

The first SSG focused on defeating the Soviet strategy, rather than starting with how to use the fleet; hence changing nuclear correlation of forces and simultaneous attacks in all theaters. As Owens, Cebrowski, and Wolkensdorfer developed and refined their concepts, Captain Ken McGruther, a protégé of VADM Art Moreau (OP-06), shared the SSG’s findings and thinking with OPNAV, which was developing the outlines of a similar strategy. In the fall of 1981, the Advanced Technology Panel (ATP) had new intelligence and turned to the SSG to conduct a wargame. In April 1982, the SSG conducted their fourth wargame using Owens’ and Cebrowski’s schemes. VCNO Bill Small brought the ATP (consisting of major leaders in OPNAV) to Newport for two days to review the game’s results and decided to use them as a basis for pushing Navy programs. CNO Hayward had the SSG (Owens and Cebrowski) brief the Navy flags. By their count, they gave their top-secret briefing to 162 flag officers, often receiving pushback, but creating a shared appreciation for their schemes. CNO James Watkins convened his first Navy CINC’s conference in Newport in October 1982. What was scheduled to be a 45-minute Owens/Cebrowski brief at the end of a day continued for hours, followed by then-CINCSOUTH, soon to be CINCPAC, Admiral Bill Crowe talking to Cebrowski over a map of the Pacific on the hood of a car discussing how the strategy would work in that theater. Changes to war plans began in earnest following that conference.

The first two SSGs played the theater CINCs in the Global War Games in 1982 and 1983 as another way to educate the participants on the strategy and campaigns while continuing to refine them. 1984 began a second five-year series of Global War Games focused on fighting an extended war, exposing more officers from all services and senior government officials to the strategy as participation expanded each year.

I was in the second row when SECNAV Lehman met with the SSG in Newport. He was enthusiastic about the strategy. However, he would say that whatever the question was, the answer was 600 ships.

How did the SSG, and through it the Maritime Strategy, influence and spur innovation in real-world fleet operations and exercises, both at the theater and tactical levels? How did the SSG’s extensive travel to operational fleet commands, and the feedback received from the theater commands and flag ranks, help influence the strategy?

As I mentioned, initial visits to operational commands first illustrated the disconnects in the timelines for attacking the Soviets. Both visits to the commands and their participation in SSG games creatively addressed the complex issues and enhanced communication contributing to consensus and commitment to action. Three of the major operational/tactical innovations were combined-arms ASW and the use of land masking to shield ships from Soviet AS-4 and AS-6 missiles, requiring their bombers to come into the teeth of fleet air defenses to attack, and the use of Marine Corps Tactical Air Operations Centers.

After serving as executive assistant to Vice Admiral Lee Baggett (OP-095) working to reconcile Navy programs with the strategy, Owens took command of SUBRON 4 in Charleston, SC. There he exchanged an officer with Jake Tobin’s VP squadron in Jacksonville, FL so that they could work on covert communications and combined ops at every opportunity. As Chief of Staff at COMSUBLANT, Owens helped to initiate no notice exercises for deploying the whole Atlantic Submarine force in three days – as the timelines were key. In command, both Cebrowski and Owens conducted wargames to familiarize subordinates with the strategy.

One part of the plan was to use AWACS to surveil the Barents and Greenland seas and provide targeting data on Soviet surface action groups to our subs. Then-Rear Admiral J.D. Williams commanding SUBGRU 2 worked with OPNAV to make Link 11 interoperable (the program managers had developed different versions) and conduct exercises to execute that concept.

As a reservist I also participated in NATO combined arms ASW exercises in 1986 and 1988 as we implemented them with our allies. The 1988 exercise involved a mobile ASW command center that now Rear Admiral Jake Tobin had created. It fit in a C-141 and we took it to an AWACS base in Norway to demonstrate that we could continue command if Northwood, UK was destroyed.

Rear Admiral Hank Mustin attended a debrief of an SSG II game employing land-masking havens. After first questioning whether aircraft could launch from carriers in restricted waters, he made Vestfjord a carrier battle group bastion when commanding Second Fleet. Similarly, Pacific Fleet began exercising land masking in the Aleutians and off of Japan.

Placing a USMC TAOC in northern Norway, Thrace, and Hokkaido was key to being able to link NATO’s Air Ground Defense Environment displays and other shore-based air ‘pictures’ with U.S. Navy Link 4 and Link 11 to coordinate air and sea-based air control and land attack. Because the Marines had to work with everyone, they had the only system designed to accept all pictures. This was a key component of Cebrowski’s defense of northern Norway, and the beginnings of his net-centric warfare concepts.

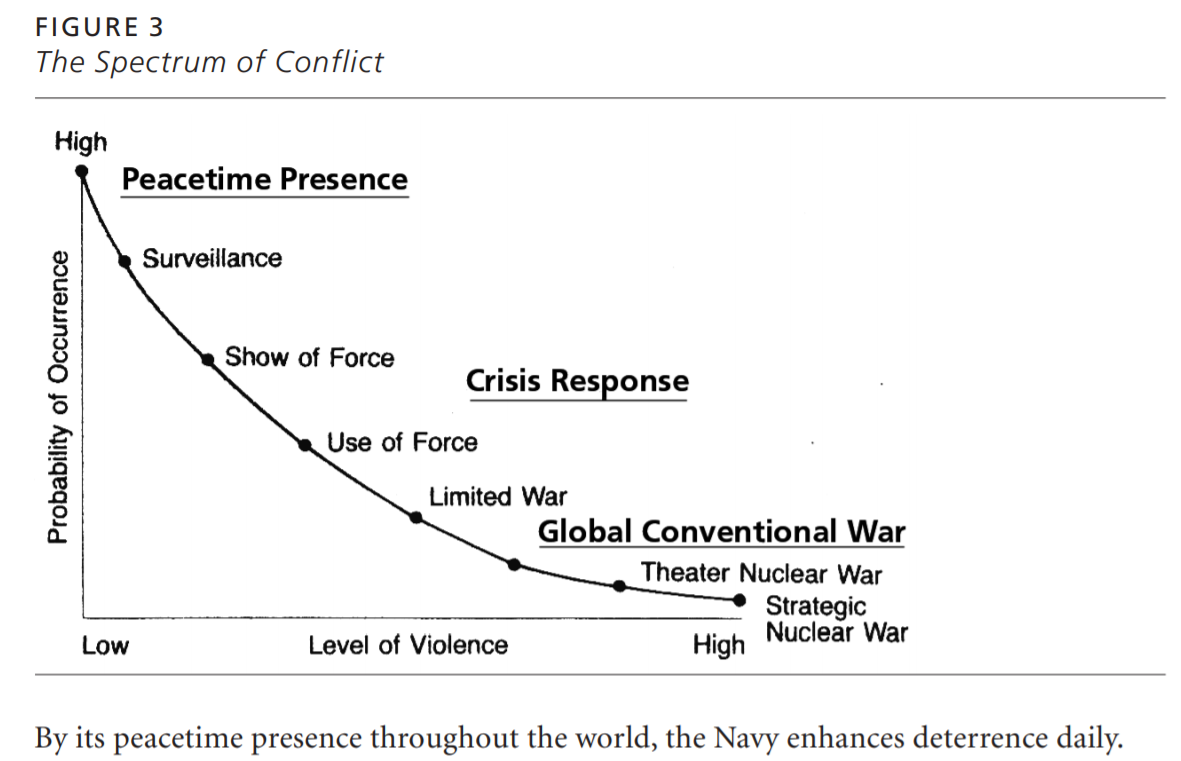

As CNOs Watkins and Carl Trost tasked subsequent SSGs to look beyond the Soviets and at other issues, the SSG interactions with operational commands spurred them to make plans for a wider range of contingencies. Often, the role of the SSG was in laying the intellectual foundations and creating templates that assisted commands in extending their planning and helped OPNAV extend the strategy to “gray-zone” operations.

Why did the Maritime Strategy “work,” if it did, and what about the process has been so hard to replicate?

John Hattendorf’s Newport Paper 19 shows how the strategy, and the way it was developed and communicated, created a renaissance in strategic thinking among the naval leadership. Few admirals could talk knowledgably about maritime strategy in the late 1970s, but essentially all could by the mid-1980s. When Hayward developed Sea Strike, he had briefing teams go around PACFLT to get the word out. He used the SSG to do the same with the top secret version of the Maritime Strategy. Subsequent CNOs continued that practice until Mike Boorda in the mid-1990s.

CNO Watkins had SSG IV work with the ATP again on a perception management campaign to deter the Soviets. Watkins viewed deterrence as a moral issue and wanted actual operations to show the Soviets that they were not ready to counter the U.S. Navy. This was highly classified. It resulted in both Navy and Joint plans. Rapid submarine force deployments and strike units moving under emissions control (EMCON) surprising Soviets were examples. The effects became apparent as Gorbachev pressed for naval arms control to stop these operations.

Where the strategy had less impact was in aligning Navy programming given the power of the platform barons; as demonstrated by VCNO Bill Small’s and many other memos.

Replicating the strategy has proven difficult for many reasons.

Some point to Goldwater-Nichols shifting the planning to the Combatant Commanders. While true, it does not relieve the Navy of the need to generate concepts for its best use and have that conversation with the COCOMs as they develop their plans. The COCOMs rely upon their service components as their principal advisors.

A much bigger driver is that since the CNO lost control of navy operations in 1958, OPNAV has been focused on programming, not warfighting. CNO Watkins told his first SSG to tell him how to win without buying another **** thing. That’s not how OPNAV thinks. The COCOMs have to think that way, and then identify the things that they need, which rarely are platforms, but are capabilities like logistics, lift, electronic warfare, surveillance, and communications interoperability. The Pentagon view from my experience in the 2000s is that the COCOMs are always asking for too much with their short-term focus, therefore their Integrated Priority Lists are ignored. Ignoring their priorities for decades results in the short-term becoming the long-term. Enemies in the Pentagon are other claimants on DoD’s budget, not foreign powers.

The SSG was exceedingly helpful in bridging between the CNO, the D.C. establishment, the operating forces, both our government and foreign governments and their militaries, when it comes to strategy and issues of importance to the CNO. He tasked them with issues that he could not get answered as well elsewhere, often because the first challenge was formulating the real questions needing to be addressed. Concerned that the SSG under director Ambassador Frank McNeil had become too pol-mil and not enough mil-pol, and advised by the CNO Executive Panel on a scheme for naval warfare innovation, in 1995 CNO Boorda brought in retired Admiral Jim Hogg and changed the SSG’s mission from turning captains of ships into captains of war to naval warfare innovation. The focus of the program shifted from developing future Navy leaders by “having them sit in the seat before they got the job” (Hayward’s original intention) through addressing issues of pressing importance to the CNO, to focusing mostly on implications of future technology for naval warfare.

During the first 14 years, of the 88 Navy officers assigned to the SSG, 43 made flag, eight were promoted to four stars (along with General Tony Zinni, USMC), and 10 finished their careers with three stars. Because they continued to serve, the officers were able to further develop and implement the concepts that they had developed over their careers, putting greater substance under their contributions to the strategy. Though potential for flag rank remained a criterion, the numbers fell off with the subsequent SSGs. Why the naval warfare innovation scheme failed to affect the Navy in a manner similar to the early SSGs is a good subject to explore in the future.

One of the many new aspects of the Maritime Strategy is a push to include more use of the Naval Reserves, something that appears was linked to Secretary Lehman’s involvement and his realignment of the reserve forces to more directly support the active Navy. As a reservist at the time, can you describe that change and how the reserve-active relationship changed, if it did?

Lehman’s role as a reservist did help make the Naval Reserve air more relevant. Reserve air squadrons had active-duty officers running the squadrons of selective reservists. CNO Hayward did away with the similar structure in the surface reserve as the ships could not be properly maintained. My experience in having three reserve commands was that contributing to the gaining commands took a far second to loyalty to the Naval Reserve program in consideration for reserve flag promotions. I believe this changed after Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003.

What lessons can be taken from the 1980s for engaging in modern great power competition, both specifically about the role of the SSG and its functionality, and more generally about the centrality of the Maritime Strategy in 1980s great power competition?

First, our strategy must begin with defeating our adversaries’ strategies. DoD’s approach of focusing on shortfalls creates a laundry list far greater than budgets can cover, even when budgets are going up. The early SSGs were able to identify several things that would make a big difference.

Secondly, though some exceptional officers (such as Vice Admiral Stuart Munsch) can bridge the gap, the culture and incentives for programming in OPNAV and the Pentagon culture and processes make creating a similar maritime strategy in the Pentagon exceedingly difficult. The audiences are principally the Congress, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, and the American public, rather than the COCOMs and our adversaries. Making programming align with strategy has never happened, though CNOs have regularly reorganized OPNAV in pursuit of that objective. Also, as Peter Swartz has pointed out, required joint duty assignments results in many of the most talented Navy officers going to the Joint Staff rather than OPNAV, and Navy strategy and policy specialists often do not serve multiple tours in their specialty, where they could be mentoring and bringing the following generations along.

The Center for Naval Warfare Studies at the Naval War College continues to do great work. However, they simply do not have the reach, nor the clout of a CNO SSG.

The CNO SSG in the 1980s was:

- Composed of O-6s at the top of their specialties and selected for their future promise by the CNO

- Focused on warfighting and operations rather than programs

- Given access to all levels of national intelligence and service special access programs

- Given broad access to U.S., foreign government, and military officials as well as top academics and think tanks

- Supported in an intellectual environment at the Naval War College and having access to analysis and games

- Given a rigorous program of study and time to think and learn about the Navy, joint forces, and the U.S national security establishment

- Accepting tasking only from the CNO

- Communicating concepts broadly across U.S. and foreign security establishments

As such, it served an essential function in creating and implementing the 1980s Maritime Strategy, and could again make a big difference.

The Navy needs campaigns of learning that affect both programming and strategy, operations, and tactics. People cite the role of the Naval War College in the interwar years in building on Prussian military science of study, analysis, games, map and field exercises that evolved into the General Board of ex-officio and selected active and retired flag officers focused on fleet design. They worked closely with the Naval War College on games and Fleet Problem exercises that fed into war plans and fleet designs. Following WWII, the Naval War College no longer performed its driving role. With defense reform, the CNO and OPNAV became more isolated both from concepts developed at the Naval War College and the fleets; stove-piped into a PPBS paradigm of systems analysis that increasing relied on campaign simulations rather than prototyping.

For a time, the SSG served to recreate the kinds of interactions that existed in the interwar period. A Navy campaign of learning needs to recreate these kinds of interactions between theoretical and practical experiences. The COCOMs are allies in such a quest, not adversaries.

Dr. Hanley served with the first eighteen Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Groups as an analyst, program director, and deputy director. He earned his doctorate in operations research and management science at Yale University. A former U.S. Navy nuclear submarine officer and fleet exercise analyst, he served as special assistant to Commander in Chief, U.S. Forces Pacific; in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (Offices of Force Transformation; Acquisition, Technology and Logistics; and Strategy); and as deputy director of the Joint Advanced Warfighting Program at the Institute for Defense Analyses. Retiring from government in 2012 after serving as director for strategy at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, he is now an independent consultant.

Joe Petrucelli is an assistant editor at CIMSEC, a reserve naval officer, and an analyst at Systems, Planning and Analysis, Inc.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s own, and do not necessarily represent the positions of employers, the Navy or DoD.

Featured Image: December 1, 1988 – A bow view of the aircraft carrier USS CONSTELLATION (CV-64) underway with ships of Battle Group Delta. (National Archives photo by ENS Brad Gutillas)