By LT Sean Lavelle, USN

There are two components to military competency: understanding and proficiency. To execute a task, like driving a ship, one must first understand the fundamentals and theory—the rules of navigation, how the weather impacts performance, how a ship’s various controls impact its movement. Understanding is stable and military personnel forget the fundamentals slowly. Learning those fundamentals, though, does not eliminate the need to practice. Failing to practice tasks like maneuvering the ship in congested waters or evaluating potential contacts of interest will quickly degrade operational proficiency.

In the coming decades, human understanding of warfighting concepts will still be paramount to battlefield success. Realistic initial training and high-end force-on-force exercises will be critical to building that understanding. However, warfighters cross-trained as software developers will make it far easier to retain proficiency without as much rote, expensive practice. Their parent units will train them to make basic applications, and they will use these skills to translate their hard-won combat understanding into a permanent proficiency available to anyone with the most recent software update.

These applications, called software-defined tactics, will alert tacticians to risk and opportunity on the battlefield, ensuring they can consistently hit the enemy’s weak points while minimizing their own vulnerabilities. They will speed force-wide learning by orders of magnitude, create uniformly high-performing units, and increase scalability of conventional forces.

Vignette

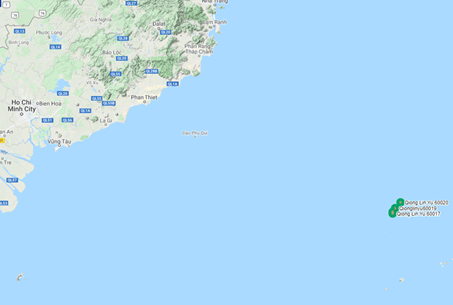

Imagine an F-35 section leader commanding two F-35 fighters tasked to patrol near enemy airspace and kill any enemy aircraft who approach. As the F-35s establish a combat air patrol in the assigned area, the jet’s sensors indicate there are two flights of adversary aircraft approaching the formation, one from off the nose to the north and the other off the right wing, from the east. Each of these flights consists of four bandits that are individually overmatched by the advanced F-35s. Safety is to the south.

These F-35s have enough missiles within the section to reliably kill four enemies, but are facing eight. Since the northern group of bandits are a bit closer, the section leader decides to move north and kill them. The section’s volley of missiles all achieve solid hits, and there are now four fewer enemy aircraft to threaten the larger campaign.

Now out of missiles, the section turns south to head back home. That’s when the section leader realizes the mistake. As the F-35s flowed northward, they traveled farther away from safety while the eastern group of bandits continued to close on the F-35s, cutting off their path home.

The only options at this point are to try to travel around the bandits or go through them. A path around them would run the fighters out of fuel, so the flight leader goes straight for the four enemy aircraft, hoping that the bandits will have seen their friends shot down and run away in fear.

The gambit fails, however, and the remaining enemy aircraft close with the F-35s and shoot them down. What should have been an easy victory ended in a tactical stalemate, and in a war where the enemy can build their simple aircraft faster than America can build complex F-35s, the 2:1 exchange ratio is in their favor strategically.

This could have gone differently.

Persistent and Available Tactical Lessons

Somebody in the F-35 fleet had likely made a mistake similar to this example during a training evolution long before the fateful dogfight. They might have even taken a few days out of their schedule to write a thoughtful lessons-learned paper about it. This writing is critically important. It communicates to other pilots the fundamental knowledge required to succeed in combat. However, success in combat demands not just understanding, but proficiency as well. An infantryman who has not fired a rifle in a few years likely still understands how to shoot, but their lack of practice means they will struggle at first.

Under a software-defined tactics regime, in addition to writing a paper, the pilot could have written software that would have alerted future pilots about the impending danger. While those pilots would still need to understand the risk, ever-watching software would alert them to risks in real-time so that a lack of recent practice would not be fatal. A quick software update to the F-35 fleet would have dramatically and permanently reduced the odds of anyone ever making that mistake again.

The program would not have had to be complex. It could have run securely, receiving data from the underlying mission system without transmitting data back to the aircraft’s mission computers. This one-way data pipe would have eliminated the potential for ad-hoc software to accidentally hamper the safety of the aircraft.

The F-35’s mission computer in our example already had eight hostile tracks displayed. The F-35’s computer also knew how many missiles it had loaded in its weapons bay. If that data were pushed to a software-defined tactics application, the coder-pilot could have written a program that executed the following steps:

- Determine how many targets can be attacked, given the missiles onboard.

- If there are enough missiles to attack them all, recommend attacking them all. If there are more hostile tracks than missiles (or a predefined missile-to-target ratio), run the following logic to determine which targets to prioritize.

- Determine all the possible ordered combinations of targets. There are 1,680 combinations in the original example—a small number for a computer.

- For each combination, simulate the engagement and determine if an untargeted aircraft could cut off the escape towards home. Store the margin of safety distance.

- If a cutoff is effective in a given iteration, reject that combination of targets and test the next one.

- Recommend the combination of targets to the flight commander with the widest clear path home. Alert the flight commander if there is no course of action with a clear path home.

This small program would have instantly told the pilot to engage the eastern targets, and that engaging the targets to the north would have allowed the eastern targets to cut off the F-35s’ route to safety. Following this recommendation would have allowed the F-35s to maintain a 4:0 kill ratio and live to fight another day.

A simple version of this program could have been written by two people in a single day—16 man-hours—if they had the right tools. Completing tactical testing in a simulator and ensuring the software’s reliability would take another 40-80 man-hours.

Alternatively, writing a compelling paper about the situation would take a bit less time: around 20-40 hours. However, a force of 1,000 pilots spending 30 minutes each to read the paper would require 500 man-hours. Totaling these numbers, results in 96 man-hours on the high-end for software-defined tactics versus 520 man-hours on the low-end for writing and reading. While both are necessary, writing software is much more efficient than writing papers.

To truly train the force not to make this mistake without software-defined tactics, every pilot would need to spend around five hours—a typical brief, simulator, and debrief length—in training events that stressed the scenario. That yields an additional 10,000 man-hours, given one student and one instructor for each training event. At that point, all of the training effort might reduce instances of the mistake by about 75%.

To maintain that level of performance, aircrew would need to practice this scenario once every six months in simulators. That is 10,000 hours every six months. Over five years, you’d need to spend more than 100,000 man-hours to maintain proficiency in this skill across the force.

Software-defined tactics applications do not need ongoing practice to maintain currency. They do need to be updated periodically to account for tactical changes and to improve them, though. Budgeting 100 man-hours per year is reasonable for an application of this size. That is 500 man-hours over five years.

Pen-and paper updates require 100,000 man-hours for a 75% reduction in a mistake. Software-driven updates require 596 man-hours for a nearly 100% reduction. It is not close.

When a software developer accidentally creates a bug, they code a test that will alert them if anyone else ever makes that same mistake in the future. In this way, a whole development team learns and gets more reliable with every mistake they make. Software-defined tactics offer that same power to military units.

Software Defined Tactics in Action

While the F-35 example is hypothetical, software-defined tactics are not. The Navy’s P-8 community has been leveraging a software-defined tactics platform for the last four years to great effect. The P-8 is a naval aircraft primarily designed to hunt enemy submarines. Localization—the process by which a submarine-hunting asset goes from initial detection to accurate estimate of the target’s position, course, and speed—is among the most challenging parts of prosecuting adversary submarines.

On the P-8, the tactical coordinator decides on and implements the tactics the P-8 will use to localize a submarine. It takes about 18 months of time in their first squadron to qualify as a tactical coordinator and demonstrate reliable proficiency in this task. These months include thousands of hours of study, hundreds of hours in the aircraft and simulator, and dozens of hours defending their knowledge in front of more experienced tacticians.

When examining the data the P-8 community collects, there is a clear and massive disparity in performance between inexperienced and experienced personnel. There is another massive disparity between those experienced tacticians who have been selected to be instructors because of demonstrated talent and those who have not. In other words, there are both experience and innate talent factors with large impacts on performance in submarine localization.

The community’s software-defined tactics platform has made it so that a junior tactician (inexperienced and possibly untalented) with 6-months of time in platform performs exactly as well as an instructor (experienced and talented) with 18-months in platform. It does this largely by reducing tactician mistakes—alerting them to the opportunities the tactical situation presents and dissuading them from enacting poor tactical responses.

This makes the P-8 force extremely scalable in wartime. In World War II, America beat Japan because it was able to quickly and continually train high-quality personnel. It took nine months to train a basic fighter pilot in 1942. It takes two or three years to go from initial flight training until arriving at a fleet squadron in 2021. Reducing time to train with software-defined tactics will restore that rapid scalability to America’s modern forces.

The P-8 community has had similar results for many tactical scenarios. It does this, today, with very little integration into the P-8s mission system. Soon, its user-built applications will be integrated with a one-way data pipe from the aircraft’s mission system that will enable the full software-defined tactics paradigm. A team called the Software Support Activity at the Naval Air Systems Command will manage the security of this system and provide infrastructure support. Another team consisting of P-8 operators at the Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Weapons School will develop applications based on warfighter needs.

Technical Implementation

Implementing this paradigm across the US military will yield a highly capable force that can learn at speeds orders of magnitude faster than its adversaries. Making the required technical changes will be inexpensive.

On the P-8, implementing a secure computing environment with one-way data flow was always part of the acquisition plan. That should be the case for all future platform acquisitions. All it requires is an open operating system and a small amount of computing resources reserved for software-defined tactics applications.

Converting legacy platforms will be slightly more difficult. If a platform has no containerized computing environment, it is possible to add one, though. The Air Force recently deployed Kubernetes—a framework that allows for securely containerized applications to be inserted in computing environments—on a U-2. Feeding mission-system data to this environment and allowing operators to build applications with it will enable software-defined tactics.

If it is possible to securely implement this on the U-2, which was built in 1955, any platform in the U.S. arsenal can be modified to accept software-defined tactics applications.

Human Implementation

From a technical standpoint, implementing this paradigm is trivial. From the human perspective, it is a bit harder. However, investing in operational forces’ technical capabilities without the corresponding human capabilities will result in a force that operates in the way industry believes it should, rather than the way warfighters know it should. A tight feedback loop between the battlefield reality and the algorithms that help dominate that battlefield is essential. Multi-year development cycles will not keep up.

As a first step, communities should work to identify the personnel they already have in their ranks with some ability to develop software. About a quarter of Naval Academy graduates enter the service each year with majors that require programming competency. These officers are a largely untapped resource.

The next step is to provide these individuals with training and tools to make software. An 80-hour, two-week course customized to the individual’s talent level is generally enough to get a new contributor to a productive level on the P-8’s team. A single application pays for this investment many times over. Tools available on the military’s unclassified and secret networks like DI2E and the Navy’s Black Pearl enable good practices for small-scale software development.

Finally, this cadre of tactician-programmers should be detailed to warfare development centers and weapons schools during their non-operational tours. Writing code and staying current with bleeding-edge tactical issues should be their primary job once there. Given the significant contribution this group will make to readiness, this duty should be rewarded at promotion boards to maintain technical competence in senior ranks.

A shortcut to doing this could be to rely on contractors to develop software-defined tactics. To maximize the odds of success, organizations should ensure that these contractors 1) are co-located with experienced operators, 2) are led by a tactician with software-development experience, 3) can deploy software quickly, 4) have at least a few tactically-current, uniformed team members, and 5) are funded operationally vice project-based so they can switch projects quickly as warfighters identify new problems.

The Stakes

Great power competition is here. China’s economy is now larger than America’s on a purchasing parity basis. America no longer has the manufacturing capacity advantage that led to victory in World War II, nor the ability to train highly-specialized warfighters rapidly. To maintain America’s military dominance in the 21st century, it must leverage the incredible talent already resident in its armed forces.

When somebody in an autocratic society makes a mistake, they hide that mistake since punishment can be severe. The natural openness that comes from living in a democratic society means that American military personnel are able to talk about mistakes they have made, reason about how to stop them from happening again, and then implement solutions. The U.S. military must give its people the tools required to implement better, faster, and more permanent solutions.

Software-defined tactics will yield a lasting advantage for American military forces by leveraging the comparative advantages of western societies: openness and a focus on investing in human capital. There is no time to waste.

LT Sean Lavelle is an active-duty naval flight officer who instructs tactics in the MQ-4C and P-8A. He leads the iLoc Software Development Team at the Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Weapons School and holds degrees from the U.S. Naval Academy and Johns Hopkins University. The views stated here are his own and are not reflective of the official position of the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

Featured image: A P-8A Poseidon conducts flyovers above the Enterprise Carrier Strike Group during exercise Bold Alligator 2012. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Daniel J. Meshel/Released)