By LCDR James Landreth, USN, and LT Andrew Pfau, USN

In Forging the Apex Predator, we published the results of a new analytical model that defined the limitations and constraints for the United States Navy’s Next Generation Attack Submarine (SSN(X)) concept of operations (CONOPS) for coordinating multiple unmanned undersea vehicles (UUV). Using a Model Based Systems Engineering approach, we studied tradeoffs associated with the number of UUVs, crew complement and UUV crew work schedule. The first iteration of our analysis identified crew complement as the limiting factor in multi-UUV, or “swarm,” operations. Identifying ways to maximize UUV operations with the small footprint crew required aboard submarines is critical to future SSN(X) design. Not all potential UUV missions require continuous human operator involvement. Seafloor surveys, mine detection, and passive undersea cable monitoring for ships can all occur largely independent of human supervision. The damage to Norwegian undersea cables in late 2021, potentially caused by a UUV, hints at the critical nature of this capability for 21st century conflict.1 By identifying operations that require less human supervision, CONOPs for SSN(X) can be tailored to maximize crew and UUV employment. The requirements for training and manning the crews to employ UUVs must be part of the considerations of creating the SSN(X) program.

The submarine force needs sailors with specialized skills to maintain, operate and integrate UUVs into SSN(X) operations. Because the submarine force and the United States Navy at large lack a documented, repeatable, and formalized process for training UUV operators and maintainers, the qualitative concept and computational model presented in this article offers a bridge to scaling multi-UUV operations. The Navy needs to develop codified training and manning requirements for UUV operations and the infrastructure, both physical and intellectual, to support unmanned systems operations. The recommendations discussed here are focused on the specific use case of UUVs deployed from manned submarines.

Defining the Human Operator’s Role in “The Loop”

In order to define a strategy to man SSN(X)’s UUV mission, the submarine force must first define the possible operational and maintenance relationships between man-unmanned teams. Once the desired relationships are defined, then the relevant activities can be listed and manpower estimates can be made for each SSN(X) and for the entire fleet. The importance of this definition and the resultant estimates cannot be understated. For example, launch and recovery of a medium UUV may be seen as consistent with existing Navy Enlisted Classifications (NECs) currently required in torpedo rooms across the fleet. Novel functions like “coordination of autonomous UUV swarms” has many supporting tasks that the Navy’s education enterprise is not yet resourced to meet. Identification of the human tasks required to meet the concept of operations (CONOP) is an essential component of integrated design for SSN(X).

The original model optimized five primary variables with a number of trial configurations, and found the most critical component for maximizing the battle efficiency of SSN(X)’s UUVs was crew support. Specifically, the model identified that the human resources consumed per UUV was the limiting relationship for the UUV swarm size deployable from a single hull. The first version of the trade study varied (a) the number of UUV crews available to support UUV operations and (b) the duration of these shifts, and used a human-in-the-loop configuration, which established a 1:1 relationship between crew and UUV. In order to employ multiple UUVs at once, the model consumed additional UUV crews for each UUV operating and/or increased the length of UUV crew’s shift. This manpower intensive model quickly constrained the number of UUVs that a single hull could employ at once.

Informed by the limitations that human resources placed on SSN(X)’s UUV mission, we updated the systems model to inform the critical task of “manning the unmanned systems.” Submariners and those who support their operations know the premium placed on each additional person inside the pressure hull. Additional crew members can limit the duration of a mission whether by food consumption, bed space, or breathing too much oxygen. As a result, any CONOP that adds a significant human compliment inside the skin of SSN(X) is likely to founder. Additionally, personnel operating and maintaining the UUVs will have a specific set of training, proficiency and career pathway requirements, whose cost will scale with the complexity of the UUV system and CONOP.

The original model was based on unmanned aerial systems (UAVs) operations and followed the manning concept of Group 5 UAVs, where one pilot is consumed continuously by an armed drone. Significant differences in operating environments between UAVs and UUVs necessitate different operating models. Due to the rapid attenuation of light and electronic signals in the undersea domain, data exchange between platforms occurs at relatively low speeds over comparatively limited distances unless connected by wire. This means that the global continuous command, control and communication CONOP available to UAVs will not transfer to UUVs. Instead, SSN(X) UUV operators will control their UUVs during operations relatively close to their manned platform, where the mothership and UUVs will share the same water space during launch and recovery. Communications at longer range will occur less frequently and be status updates to the operator rather than continuous or detailed. Separating the concern about counter detection and interception of acoustic signals, communications at range is possible.2

The unique physical characteristics of the underwater domain make communications one of the most challenging aspects of multi-UUV operations.

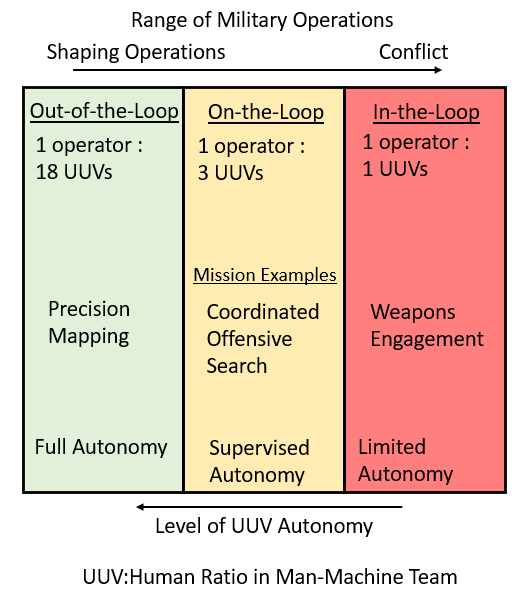

Putting connectivity differences aside, the manpower required for this human-in-the-loop model is unnecessarily limiting for the expected UUV CONOP. Alternate models are presented in Autonomous Horizons: The Way Forward, which details the roles for three man-machine team concepts: human-in-the-loop, human-on-the-loop and human-out-of-the-loop. A human-on-the-loop scenario would allow an operator to supervise a coordinated swarm rather than a single asset. This would be less efficient than fully autonomous operation, but dramatically improve the number of UUVs a SSN(X) could deploy as a swarm. Operations performed in this control mode would be limited to those that do not present a hazard to humans but require careful supervision such as a coordinated offensive search or scanning a mine field. Finally, a human-out-of-the-loop scenario would require the fewest human resources and maximize the number of UUVs an SSN(X) could effectively employ, but its mission scope is assumed to be limited to non-kinetic activities (“shaping operations”). Figure 1 provides a visualization of how mission role and levels of autonomy impact human resource requirements.

Given the multi-mission role that SSN(X) and its UUV swarm will play, the updated model offers three man-machine team configurations that could be matched to given missions. SSN(X) requirements officers, submarine mission planners and submarine community managers must understand these man-machine configurations in order to inform SSN(X)’s human resource strategy:

- In-the-Loop. The authors assumed that certain missions such as weapons engagement will continue to require a human-in-the-loop architecture where a human is continuously supervising or controlling the actions of a given UUV. As such, the original model results were retained to represent these activities and provide a baseline for comparison against the two other architectures.

- On-the-Loop. Directed missions like coordinated search or enemy tracking that could be precursors to human-in-the-loop scenarios benefit from the supervision of a human operator. In a human-on-the-loop architecture, the UUV operator is collaborating with one or more UUVs. The UUVs operate with a degree of autonomy and prompt the operator when they require human direction. The study assumed each operator could coordinate up to 3 UUVs, though this number is a first approximation. Further experimentation might show that this number could be significantly larger.

- Out-of-the-Loop. In this architecture, the UUV(s) engage in fully autonomous activities. They remain receptive to commands from the operator but require no input to perform their assigned role. The study assumed that an operator could coordinate up to 18 UUVs in a fully autonomous mode.3 However, this could scale as a multiple if SSN(X) could perform simultaneous launch and recovery operations from multiple ocean interfaces.

By affording the model the scale available from on-the-loop and out-of-the-loop control modes, the predicted swarm of UUVs could easily triple the area surveyed in a 24-hour period. Detailed results of the updated model are provided in Appendix 1. The submarine force must first consider its need to generate UUV crews for SSN(X), regardless of their mode of operation. More complex UUV operations will require greater skill investment, and more actively used UUVs per hull will impose a greater maintenance burden on the crew. Figure 1 illustrates the important relationship between UUV complexity, control mode, mission role across the range of military operations.

Current Situation Report

The Navy’s guiding document for unmanned systems, the Unmanned Campaign Framework (UCF), addresses how Type Commanders will “equip” the fleet, but the Navy should expand the UCF to include how Type Commanders will perform their “man and train” missions.4 The realities of unmanned technologies will require new training for existing rates and potentially new specialized ratings. The “man and train” demand signals will become louder as the skills required for UUV operations and maintenance grow as a function of UUV complexity5 and scale6 of operations. Establishing a central schoolhouse and formal curriculum for officer and enlisted UUV skills is a strategic imperative. As a reminder, SSN(X)’s requirements demand complex UUV operations at scale.

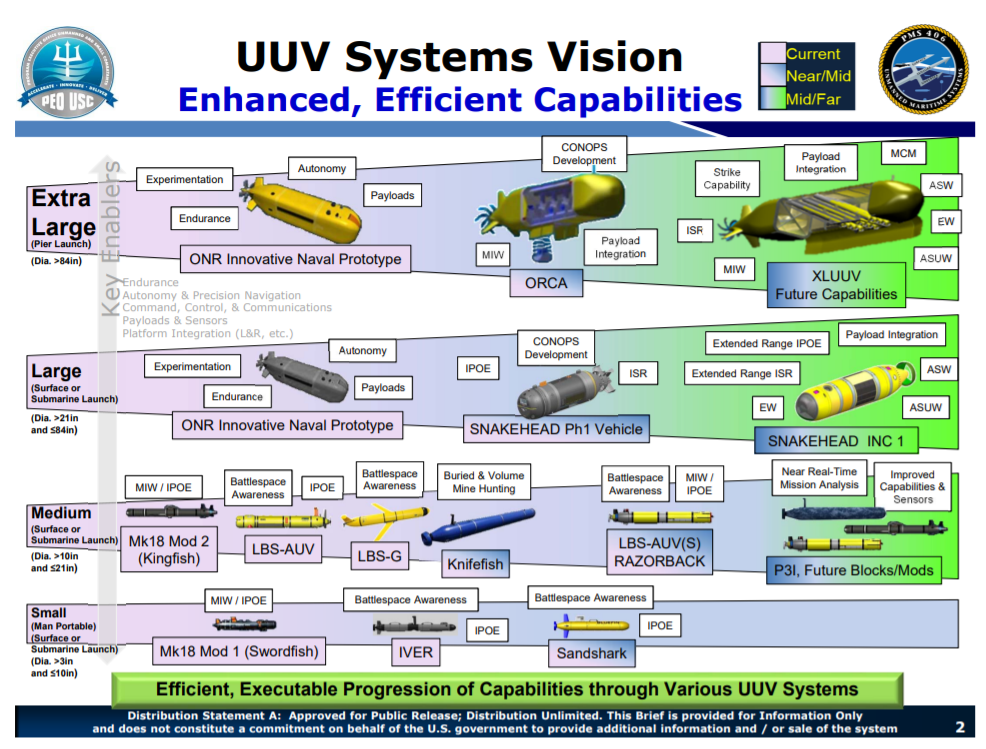

The Navy has organized UUVs into four primary groups based on size. Figure 2 shows the categorization of UUVs into small, medium, large and extra-large UUV (SUUV, MUUV, LUUV, and XLUUV). The current groupings are based on the ocean interface required to deploy each UUV, but as the Navy develops its UUV CONOP, the submarine force would be wise to borrow from the similar categorization of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) in the Joint Unmanned Aircraft Systems Minimum Training Standards.7 The five UAV groupings consider not only physical size, mission, and operational envelop but also the qualification level required of the operators. These categories will determine how each UUV category will be employed, with SUUV, MUUV and even some LUUVs able to be deployed from manned submarine motherships. The complexity and skill required to operate UUVs will also scale with size, with larger UUVs able to carry more sensors at greater endurance. These categorizations easily translate into training and manpower requirements for operations, with more training and personnel required for larger UUVs.

Almost all of the platforms illustrated in Figure2 are currently in the experimental phase, with only a few copies of each UUV platform available for test and evaluation. At least one UUV platform, the Knifefish, is moving into low-rate initial production.9 As the Navy moves to acquire more UUVs, it will have to transition its training of sailors from an ad hoc deployment specific training to codified schoolhouses.

In line with the experimental nature of current UUVs, the units that operate and maintain UUV systems also exist in the early phases. The Unmanned Undersea Vehicle Squadron 1 (UUVRON 1), and Surface Development Squadron 1 (SURFDEVRON 1) are tasked with testing unmanned systems and developing tactics, techniques, and procedures for their operation. Task Force 59, operating in the 5th Fleet area, is the first operational Navy command that seeks to work across communities to bring unmanned assets together for testing and operations. Sailors assigned to these commands will learn many unmanned-specific skills and knowledge on the job because the skills they bring from their fleet assignments may or may not be applicable. Similar to the schoolhouse challenge, establishing maintenance centers of excellence and expanding the work of development squadrons are essential pillars of the unmanned manpower strategy.10

Preparing for the Future

The Navy must train sailors for two primary UUV tasks: operations and maintenance. While the same sailor may be trained and capable of performing both tasks on UUVs, manpower models must accommodate enough personnel to simultaneously operate UUVs while performing maintenance on one or more other UUVs.

The submarine force can examine the operational training models that exists for UAVs where the size and capabilities of the UAV determine training requirements. The Department of the Navy already provides training for a range of UAV classes and missions including: RQ-21 Blackjack, ScanEagle, MQ-4 Triton, MQ-8C Fire Scout, and a number of other joint programs of record. The UAV training requirements exist in various stages of maturity, but on average exceed UUVs by several years or even decades due to early investment by both military and civilian organizations like the Federal Aviation Administration. Requirements for UAV training vary widely based on grouping. Qualification timelines for Group 1 UAVs like small quadcopters can be measured in days. Weapons-carrying or advanced UAVs like the MQ-9 Reaper require operators who have received years of training similar to manned aircraft pilots.

The Navy, Army and Marine Corps have established military occupational designations for roles related to UAVs, including maintenance and flight operations. They have established training courses to certify service operators and maintainers for a wide variety of UAV platforms. In contrast, the Navy has yet to promulgate a plan for Navy Enlisted Classifications (NEC) or Officer Additional Qualification Designations (AQD) or establish an equivalent career field for UUV operations at a level of detail consistent with legacy warfare platforms.

In addition to evaluating the transferability of lessons learned from the UAV community, the submarine force should incorporate the lessons learned from sister UUV users in the special warfare and explosive ordinance disposal domains. These communities possess the mature UUV technology and operating procedures. The experience of these communities can accelerate the nascent domain knowledge the submarine force has already established as it builds a foundation for multi-UUV operations from SSN(X). Separate from operations, the Navy will need to be able to perform organic-level maintenance tasks on UUVs at sea such as replacing circuit cards, swapping sensor packages, or maintaining propulsion units. Given SSN(X)’s heavy weapons payload requirements, an unmaintained UUV occupying a weapon’s stow will limit its intended multi-mission nature. The Navy will need to train its work force for these maintenance tasks. Just as importantly, UUVs will have to be designed for maintainability, so that basic components can be repaired or replaced at sea.

Manpower Models

However the Navy chooses to train sailors to operate and maintain UUVs, community managers will face a different set of choices when it comes to the organization and manning. There are two different models the Navy primarily uses to organize and man similar units supporting unmanned operations: directly assign sailors with the required skills to operational units or create specialized UUV detachments located in major homeports that then augment deploying units.

The most integrated model would be direct manning of submarines with sailors possessing the NEC or AQD certifying skill in operation and maintenance of UUVs. Each unit would have the number of billets necessary to meet manpower requirements and these sailors would be part of the crew, getting underway and performing duties other than those directly related to UUVs, even when UUVs are not onboard. This model would ensure continuous integration of UUV experts with the rest of the crew. While the crew may gain more knowledge from these experts, the experts may face challenges maintaining their expertise based on the needs of a given deployment. The most significant challenge to maintaining skills will be the availability of UUVs on every submarine and time at sea to practice operations.

The detachment model offers an arguably more proficient set of operators to a deploying unit, but can cause secondary impacts to warfighting culture. The Information Warfare Community (IWC) efficiently supports current submarine operations via the detachment model for certain technical operations. IWC “riders” are welcome compliments for important missions, but the augment nature means that the hosting submarine does not necessarily fully integrate the “rider’s” culture and knowledge into its own. If the submarine force adopted this model, a UUVRON at fleet concentration areas like Groton or Pearl Harbor would have administrative responsibility for sailors with the technical skills to maintain and operate UUVs. These sailors form into detachments and deploy to submarines to conduct operations while deployed. This model requires fewer personnel than a direct manning model, and these sailors will likely become more proficient in UUV operations. However, the rest of the submarine crew (and thus the force as a whole) would become less familiar with UUV operations without a permanent presence of expert sailors.

Both of the direct assignment and detachment manning models have advantages and drawbacks. Quantitatively, the submarine force must assign priorities and human resource availability to the variables within the trade space. Qualitatively, the Navy must determine how tightly UUV operators will be coupled to deploying units, and whether the detachment model can establish the desired UUV culture across the fleet.

Conclusion

Despite the unmanned moniker, UUVs will still require skilled humans to maintain and operate them. SSN(X) requirements officers, mission planners and community managers must provide early input into the types of autonomous missions SSN(X) UUVs will perform and the corresponding skill level required of sailors. To succeed, decision makers can compare the model provided in this article with existing programs of record’s training and certification requirements for UAVs. The submarine force must adopt a framework of training requirements that scales to UUV size and capability, and that framework must include whether UUV sailors will come from specialized detachments like current-day IWC riders or be integrated members of the crew. As the Navy moves UUVs from the test and evaluation to deployment phases and formalizes requirements for SSN(X), skilled sailors must be already in the fleet, ready to receive and operate these systems.

Lieutenant Commander James Landreth, P.E., is a submarine officer in the Navy Reserves and a civilian acquisition professional for the Department of the Navy. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy (B.S.) and the University of South Carolina (M.Eng.). The views and opinions expressed here are his own.

Lieutenant Andrew Pfau, USN, is a submariner serving as an instructor at the U.S. Naval Academy. He is a graduate of the Naval Postgraduate School and the U. S. Naval Academy. The views and opinions expressed here are his own.

Appendix 1: Data Comparison between System Optimized for Human-In-the-Loop versus On-the-Loop and Out-of-the-Loop Optima

| # UUV | # Crew | Miles Scanned per 24 hrs | Utilization |

| 8 | 4 | 240 | 0.25 |

| 7 | 4 | 240 | 0.29 |

| 6 | 4 | 240 | 0.33 |

| 5 | 4 | 240 | 0.4 |

| 4 | 4 | 240 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 4 | 240 | 0.67 |

| 2 | 3 | 165 | 0.69 |

Table 5. Sample Analysis Results Optimized for Man-in-the-Loop (1:1)

| # UUV | # Crew | Crew OPTEMPO | UUV Charging Bays | Charges per Day | Miles Scanned per 24 hrs | Utilization | Notes ↑↓ |

| 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 659 | 0.69 | 2.75x ↑ in miles scanned; 2.76x ↑ in utilization |

| 7 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 577 | 0.69 | 2.4x ↑ in miles scanned; 2.37x ↑ in utilization |

| 6 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 494 | 0.69 | 2.06x ↑ in miles scanned; 2.1x ↑ in utilization |

| 5 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 412 | 0.69 | 1.72x ↑ in miles scanned; 1.7x ↑ in utilization |

| 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 330 | 0.69 | 1.72x ↑ in miles scanned; 1.7x ↑ in utilization |

| 3 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 247 | 0.69 | 1.03x ↑ in miles scanned; 1.03x ↑ in utilization |

| 2 | 3 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 165 | 0.69 | No change |

Table 6. Sample Analysis Results for On-the-Loop (3:1) vs Man-in-the-Loop Optima

| # UUV | # Crew | Crew OPTEMPO | UUV Charging Bays | Charges per Day | Miles Scanned per 24 hrs | Utilization | Notes |

| 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 659 | 0.69 | No change |

| 7 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 577 | 0.69 | No change |

| 6 | 3 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 494 | 0.69 | Same output with 1 fewer crew |

| 5 | 3 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 412 | 0.69 | Same output with 1 fewer crew |

| 4 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 330 | 0.69 | Same output with 2 fewer crew |

| 3 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 247 | 0.69 | Same output with 2 fewer crew |

| 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.33 | 165 | 0.69 | Same output with 1 fewer crew |

Table 7. Sample Analysis Results for On-the-Loop (3:1) Re-Optimized

| # UUV | # Crew | Miles Scanned per 24 hrs | Utilization |

| 8 | 4 | 659 | 0.69 |

| 7 | 4 | 577 | 0.69 |

| 6 | 4 | 494 | 0.69 |

| 5 | 4 | 412 | 0.69 |

| 4 | 4 | 330 | 0.69 |

| 3 | 4 | 247 | 0.69 |

| 2 | 3 | 165 | 0.69 |

| 8 | 2 | 659 | 0.69 |

| 7 | 2 | 577 | 0.69 |

| 6 | 2 | 494 | 0.69 |

| 5 | 2 | 412 | 0.69 |

| 4 | 2 | 330 | 0.69 |

| 3 | 2 | 247 | 0.69 |

| 2 | 2 | 165 | 0.69 |

Table 8. Sample Analysis Results for Out-Of-the-Loop (18:1) vs In-the-Loop Optimal. The same performance metrics of miles scanned and utilization rates are achieved with only 2 crews for the same UUV configurations.

Appendix 2: Analysis Constraint Equations

The following equations were used to develop a reusable parametric model. The model was developed in Cameo Systems Modeler version 19.0 Service Pack 3 with ParaMagic 18.0 using the Systems Modeling Language (SysML). The model was coupled with Matlab 2021a via the Symbolic Math Toolkit plug-in. This model is available to share with interested U.S. Government parties via any XMI compatible modeling environment.

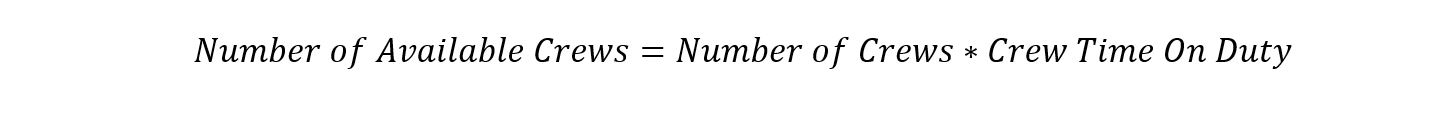

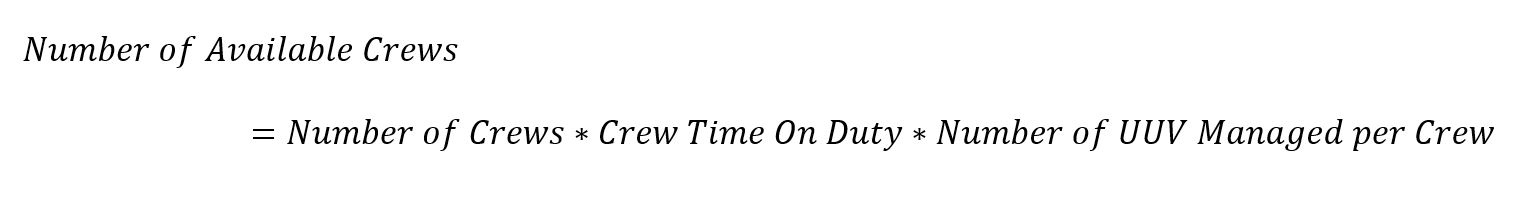

Equation 7b. Crew Availability Equation introduces a new variable called “Number of UUV Managed per Crew.” This variable represents an evolution from the first version of this study, which limited an individual crew and its UUV to a 1:1 relationship. Equation 7a. Crew Availability Equation used in the first version calculations is included for comparison.

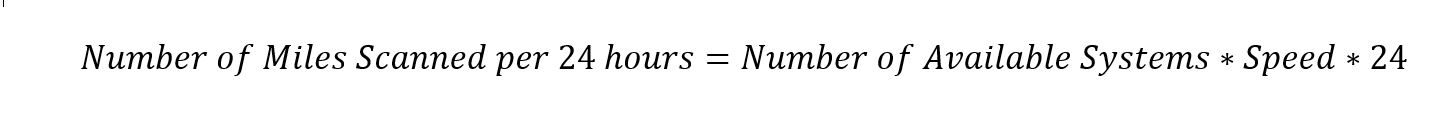

Equation 1. Scanning Equation

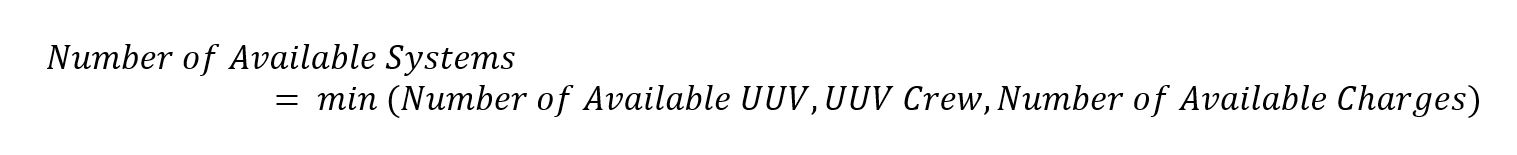

Equation 2. System Availability Equation

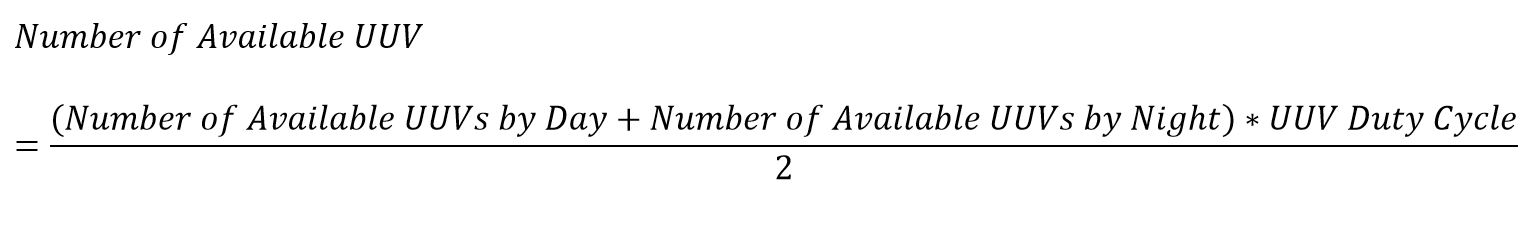

Equation 3. UUV Availability Equation

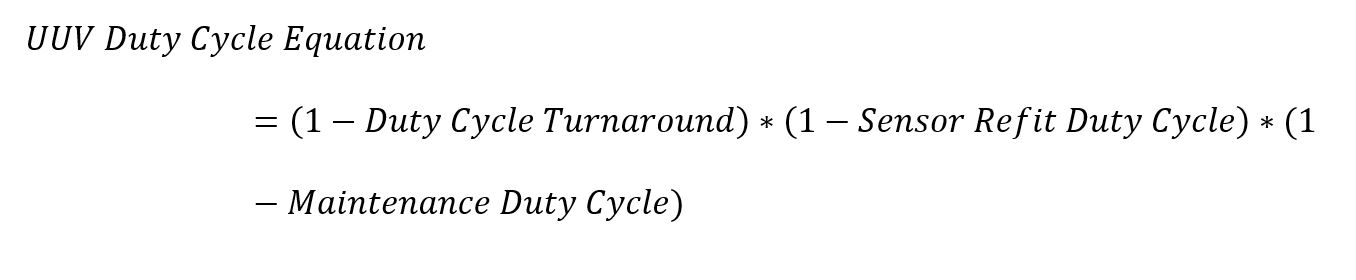

Equation 4. UUV Duty Cycle Equation

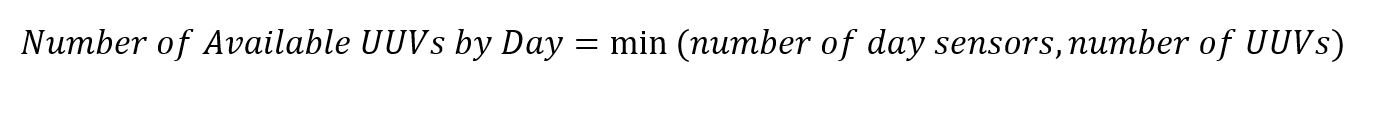

Equation 5. Day Sensor Availability Equation

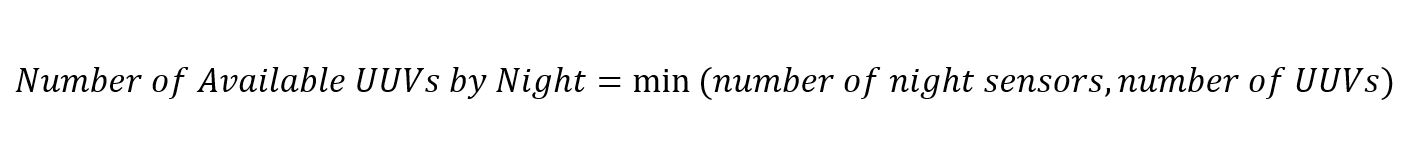

Equation 6. Night Sensor Availability Equation

Equation 7a. Crew Availability Equation

Equation 7b. Crew Availability Equation

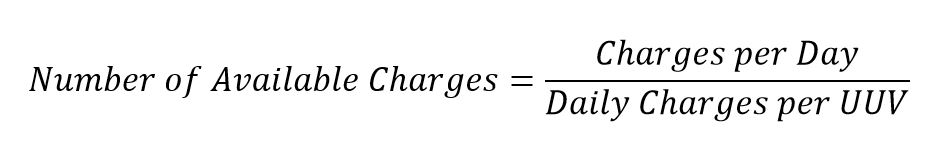

Equation 8. Charge Availability Equation

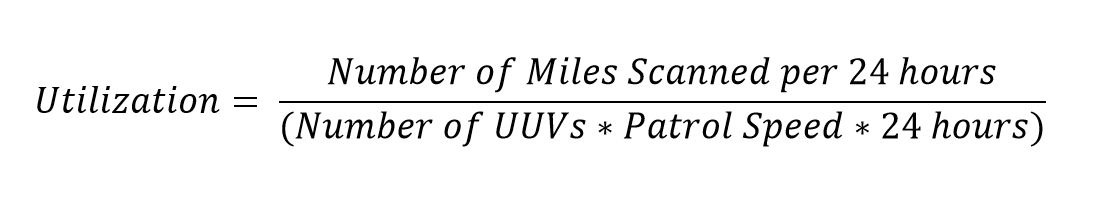

Equation 9. Utilization Score

Endnotes

1. Thomas Newdick, “Undersea Cable Connecting Norway with Arctic Satellite Station has been Mysteriously Severed”, The War Zone, Jan 10, 2022, online: https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/43828/undersea-cable-connecting-norway-with-arctic-satellite-station-has-been-mysteriously-severed

2. Milica Stojanovic, “On the Relationship Between Capacity and Distance in Underwater Acoustic Communication Channel”, ACM SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review, Vol 11, Issue 4, Oct 2007. Online: https://doi.org/10.1145/1347364.1347373

3. The basis for 18 was that the deployment and recovery of each UUV would consume approximately 4 hours in an anticipated 72-hour UUV mission (72:4 reduces to 18:1).

4. Department of the Navy, “Unmanned Campaign Framework,” Washington, D.C., March, 2021 https://www.navy.mil/Portals/1/Strategic/20210315%20Unmanned%20Campaign_Final_LowRes.pdf?ver=LtCZ-BPlWki6vCBTdgtDMA%3D%3D

5. Complexity refers to the technical sophistication of each UUV and/or the difficulty of executing a mission within a realistic battle space

6. Scale refers to the number of UUVs in a coordinated UUV operation

7. Joint Staff, “Joint Unmanned Aircraft Systems Minimum Training Standards (CJCSI 3255.01, CH1),” Washington, D.C., September 2012

8. Slide 2 of briefing by Captain Pete Small, Program Manager, Unmanned Maritime Systems (PMS 406), entitled “Unmanned Maritime Systems Update,” January 15, 2019, accessed Oct 22, 2021, at https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/Exhibits/SNA2019/UnmannedMaritimeSys-Small.pdf?ver=

9. Edward Lundquist, “General Dynamics Moves Knifefish Production to New UUV Center of Excellence,” Seapower Magazine, August 19, 2021, https://seapowermagazine.org/general-dynamics-moves-knifefish-production-to-new-uuv-center-of-excellence/

10. The end of 2021 saw initial operating capability for Task Force 59 in the 5th Fleet area of operations, which was the first unmanned Task Force of its kind.

Featured Image: BEAUFORT SEA, Arctic Circle (March 5, 2022) – Virginia-class attack submarine USS Illinois (SSN 786) surfaces in the Beaufort Sea March 5, 2022, kicking off Ice Exercise (ICEX) 2022. (U.S. Navy photo by Mike Demello)