By CAPT John P. Cordle, USN (ret.) and LCDR Reuben Keith Green, USN (ret.)

A survey of the past few years tells us the military continues to grapple with racism and extremism in its ranks:

- A Marine General uses a racial slur in an exercise field.1

- A noose is found hanging in a Black soldier’s locker.2

- A Navy Admiral uses profanity and makes “racially insensitive comments” on an aircraft carrier bridge.3

While most people would characterize this behavior as patently racist, (prejudiced against or antagonistic toward a person or people on the basis of their membership in a particular racial or ethnic group), the laws governing military personnel do not capture these egregious breaches of respect and trust.

The Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) is intended to create a consistent and consistently enforceable code of law to deal with military members accused of crimes, misconduct, or other infractions that must be dealt with in a manner unique to the military and outside the scope of the civilian legal system. Under the UCMJ, however, there is no codified enforcement mechanism for these transgressions. This article will explore codifying a UCMJ article to punish racist behavior and acts in pursuit of protecting service members, improving accountability, and supporting leaders.

The Proposed Article

By combining the expertise and experience of a former commanding officer, a military lawyer, and someone who has experienced racism firsthand, we propose the following language for a UCMJ article codifying racist behavior.

Article XXX: Racist Behavior, defined as prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against a person or people based on their membership in a particular racial or ethnic group, typically one that is a minority or marginalized, is prohibited under this article. This offense may take the form of jokes, slurs, use of divisive symbols, or specific actions up to and including violence directed at an individual because of their particular racial or ethnic group.

Next, we will explore the background of addressing racism in the U.S. military and why an addendum to the UCMJ is necessary.

Historical Context

The U.S. Navy took dramatic actions to address racism, diversity, and inclusion in the 1970s. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt overcame significant resistance to curtail discriminatory practices. While Admiral Zumwalt is heralded as one of the Navy’s all-time great reformers, his work was unfortunately incomplete. Several decades later, the Navy established “Task Force One Navy” in the wake of the spate of highly publicized police brutality incidents in the summer of 2020. The Task Force’s stated goal was to “examine barriers to minorities and make recommendations to improve diversity and inclusion within the U.S. Navy.” The Task Force completed its final report in December 2020 and made over 50 tangible recommendations. Unfortunately, an opportunity was missed when the final report did not include concrete recommendations to address racism and accountability in the Navy. However, there is no reason that their work cannot lay a solid foundation for a tangible next step: a concrete and prosecutable definition of racist actions and behavior.

The UCMJ was signed by President Harry S. Truman in May 1950 within the broader context of Jim Crow laws, pervasive in the American South until 1965. Given this backdrop, in conjunction with the UCMJ being signed on the heels of an Executive Order to integrate the U.S. military, including “racism” in the document may have been viewed as a bridge too far. Despite the equal opportunity movement of the 1960s and 1970s, no significant inroads toward codifying racism were made.

Existing Punitive Legal Framework

Within the current legal architecture, individuals who use racist language or engage in racist acts would likely be prosecuted under another UCMJ Article, such as an orders violation (Article 92, UCMJ) or, for officers, Conduct Unbecoming (Article 133, UCMJ). Alternatively, in some cases, racist misconduct could be prosecuted under the so-called General Article (i.e., Article 134), which serves as a catchall and could theoretically allow military prosecutors to use hate crime statutes. None of these statutes is designed to orient investigators and prosecutors toward the uniquely insidious evils of racism – and actions that result from it – in the ranks.

A Judge Advocate General officer (military lawyer) shared that there are several references in place that explicitly address racist acts:

-

- UCMJ Article 132 defines “unlawful discrimination” as “discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” Also, see RCM 1001, which allows “evidence in aggravation” to be presented to the members on sentencing (after the accused has been found guilty): “In addition, evidence in aggravation may include evidence that the accused intentionally selected any victim or any property as the object of the offense because of the actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, ethnicity, gender, disability, or sexual orientation of any person.

- DoDI 1325.06, Enclosure 2 lists statutory provisions that could be used to address racist behavior.4

- MILPERSMAN 1910-160 allows for administrative separation for “supremacist and extremist conduct,” which addresses misconduct related to “illegal discrimination based on race…color.”

Policy Rationale for Codifying Racist Actions and Behavior as a Specific Offense

Given this, why not leave things alone? After all, changing the UCMJ would not merely be a small definition change in regulation; it would constitute a change in military law. Despite this weighty prospect, given the documented persistent problems with racism and extremism in the military, Congress and the President should send a clear message by codifying a specific UCMJ offense that proscribes racist conduct uniformly across the U.S. military.

There are several reasons that a specific article would improve accountability and support commanders in charging individuals with racist behavior as well as educating the force, which may not understand the implications of their actions. These include:

- Disincentivizing behavior through legal proscription serves a valuable purpose: specific and general deterrence.5 In other words, showing tangible consequences for specific actions can deter some individuals from doing them and others from tolerating them.

- Promote consistency and predictability throughout the services, enabling commanders to foster healthy, respectful, and inclusive climates at the unit level. The presence of a concise definition of the word “racist behavior” would make it clear to all where the line is and how not to cross it. Some examples would help. For example, certain words are widely accepted as “racist slurs” if used to describe another person or symbols that might be racist in nature (for example, a “KKK” medallion or a noose in a workplace).

- Injecting expediency and removing ambiguity into investigations into alleged racist misconduct. One of us has directly experienced racism, and one of us has been accused of racist actions. You may be surprised to learn that in both cases, it was me – Mr. Green. In the first case, the Sailor’s informal, without merit complaint dragged on due to a lack of clarity in the UCMJ and was in the end discredited; in the second case, involving an accusation brought by a Black civilian, I was exonerated because the evidence did not support it. In both instances, a clear definition of racist actions in the UCMJ would have saved a lot of work, uncertainty, and distress and sped up the final adjudication. Cordle: I often hear my (white, male) peers share that “I never saw racism in my command,” seemingly oblivious to the fact that just because they did not witness it firsthand did not mean it had not occurred. These changes would take racist behavior out of the subjective and provide a clear and actionable definition. These examples are evocative of Justice Potter Stewart’s famous definition of pornography, “I know it if I see it.” Fortunately, with a codified UCMJ article addressing racist actions, unit commanders and service members would not have to rely on pithy turns of phrase but on comprehensive military law.

- It would allow Commanders to move prosecution to a higher level, such as courts-martial, where they could be more properly adjudicated and legally defended on appeal. Commanders are warfighters, not legal experts. They are also human and may be subject to bias (“but he is my best technician”). Similar to the recent changes in the sexual harassment arena, where the investigation and prosecution of sexual assault and related crimes have been removed from the chain of command. This change would allow commanders to focus on their given mission while giving investigations into allegations or racist actions or behavior the time, attention, and independence they demand.

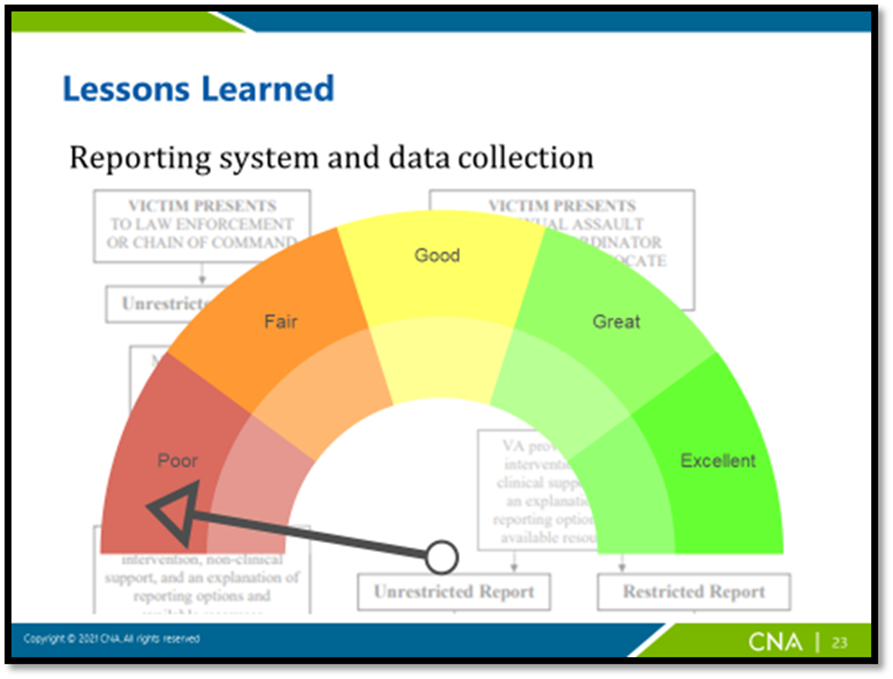

- It would enable the compilation of statistical data on the prevalence and frequency of racist behavior. It is critical to note that the absence of discrete data does not mean the issue does not exist. The Center for Naval Analyses 2022 Study on Violent Extremism notes, “this issue is an exceptionally challenging one for several reasons including, but not limited to: little existing data on the problem, poorly defined key terms, and a high degree of politicization.” The graph below (focus on the needle vice the background) illustrates this phenomenon.

Figure 1. A recent study by the Center for Naval Analysis cited “poor data quality and availability” as a barrier to determining the extent to which racist behavior is punished (Source: Center for Naval Analyses) - It would allow the service to identify and remove service members whose racist actions are prejudicial to the good order and discipline of military units. In his 2020 Lawfare article Why Extremism Matters to the U.S. Military, Navy Captain Keith Gibel, wrote that criminalizing behavior does not make it go away, “Prosecution will not stop extremist beliefs or racist behavior.” What Captain Gibel overlooks, however, is that, unlike society, the military has the option of removing a service member whose behavior is prejudicial to good order and discipline and detract from the units and, broadly, the military services from executing their missions.

- The ability to build a library of case law and establish legal precedent. The legal world is built on a foundation of precedent. Since, as we have noted, there is no data or established process, it is difficult to provide waypoints to steer by. Changing the UCMJ would begin the process of building a library of case law and established legal precedent.

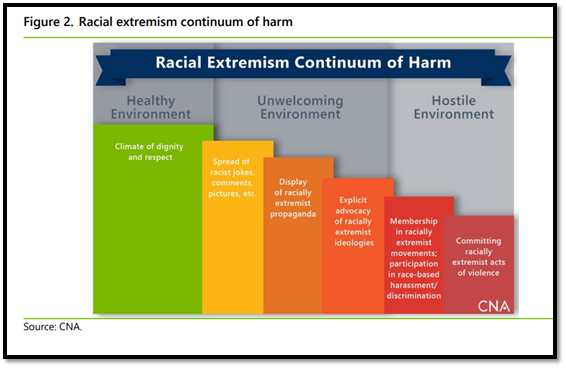

- It would send a signal to minority service members that they are being looked out for. The weight of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery still weighs heavy on the 31% of active-duty racial minorities. As a friend and mentor, former Fleet Master Chief Raymond Kemp wisely said, “for there to be a real change, there must be a compassionate ear from the unimpacted.” Giving leaders in the U.S. military both the knowledge and ability to remove the cancer of racism in the ranks will be a powerful signal to those who have been made to feel less than. It will communicate to a generation of Sailors, Soldiers, Marines, Airmen, Coast Guardsman, and Guardians that they are valued and heard, and actions against them based on their creed, color, or religion will not be tolerated. The below graph applies a concept – one that has been well vetted in the area of sexual harassment and sexual assault – to the racism conversation. The same rules apply – acceptance of small examples of bad behavior can lead to much worse – if left unchecked.

Conclusion

The Center for Naval Analyses report on violent extremism ends with a candid assessment and recommendation, “Most critical, at this pivotal moment, is the recognition that the problem of racial extremism is not one of a few bad apples, but is, in fact, a more pervasive challenge that—like sexual harassment and sexual assault—will require a more comprehensive set of solutions.” One of these would be: to make racist actions and behavior a discrete UCMJ offense. Even though making racism a UCMJ offense would undoubtedly draw partisan ire, it is a necessary change at a critical moment. Doing so will provide clarity regarding unacceptable behavior, enable a legally defensible adjudication for cases, enable the judicial system to provide guidance for commanders and individuals alike, and provide much-needed transparency in an area that has not been clearly defined for more than seventy years.

Captain John Cordle retired from the Navy in 2013 after 30 years of service. He commanded the USS Oscar Austin (DDG-79) and USS San Jacinto (CG-56), retiring as Chief of Staff for Commander, Naval Surface Forces Atlantic. He received the U.S. Navy League’s Captain John Paul Jones Award for Inspirational Leadership in 2010, the Surface Navy Literary Award, and Naval Institute Proceedings Author of the Year Award in 2019. Recently, he has teamed with his co-author, LCDR Green, in an effort to promote diversity and inclusion in the military, authoring several articles and featured as speakers on the topic at various Navy and affinity group DEI symposia over the past two years.

Lieutenant Commander Keith Green retired in 1997 after serving 22 years in the Navy. He served four department head tours, including as Executive Officer in USS Gemini (PHM-6). He is a former Legal Yeoman, Equal Opportunity Program Specialist, and leadership Instructor, and was commissioned in 1984 via Officer Candidate School. He has an MS degree in Human Resources Development. His memoir Black Officer,White Navy was acquired by a University Press and a revised edition will be republished in 2023.

References

1. Alex Horton, Two Star Marine General fired after allegations he used racial slur around subordinates, Military Times, October 2020.

2. Zelie Pollon, African American soldier says noose strung outside barracks, Reuters, June 2011

3. Linda Thomas, Navy’s Reason for discipline of Bremerton-Based Admiral, Navy Times, April 2013.

4.Appropriate courts-martial sentencing considerations include, but are not limited to, “promot[ing] adequate deterrence of misconduct.” Rules for Courts-Martial (R.C.M.) 1002(f)(3)(D). Thus, the R.C.M. identify deterrence as an important punishment consideration of courts-martial with an eye toward maintaining good order and discipline.

5. McBride, Megan, Racial Extremism in the United States: A Continuum of Harm, Center for Naval Analyses, January 2022.

Featured Image: NAVAL STATION NORFOLK (Oct. 4, 2012) Lt. Cmdr. James Raymond, center, operations officer for Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 9, stands with his squadron during a change of command ceremony. Cmdr. Brad L. Arthur relieved Cmdr. Brian K. Pummill as commanding officer of Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 9. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Timothy Walter/Released)

While I find the general idea of this article quite good, I feel the execution may be more problematic than suggested. It really comes down to the wording of the proposed offense, and how well (or poorly) it can be enforced. How does one distinguish between actions dumb or malicious?

The ever popular “reciting Rap lyrics” charge probably shouldn’t fall under the same UCMJ offence as more deliberately malicious acts such as abuse of a person or their possessions.

Perhaps a more multi-tiered approach, analogous to the difference between unauthorized absence and desertion, could provide a better path to implementing change which is both effective and fair.

Ryan – thanks for reading the article and agree completely! Getting the wording right would be challenging but possible!

Where is my comment? I said basically the same thing.

The article fails to address the growing marginalization and discrimination against non-Christian service members. Further, the failure to address the subject only wideness the discrimination gap and places non-Christian service members at additional risk.

Paul, thanks for the correction. If this moves forward your input should be part of the discussion!

Possibly you missed the title and the purpose of this article.

Since we against racism, people shall not be categorized by color, blood type, horoscope, race, ethnicity, or place of birth, nor promote biodiversity or pluralism. Because we shall against racism with believing all people are one race.

Therefore, we shall not think about policy with anthropology or evolution, nor replace “judgment of right and wrong” with “opposition to extremism.” Because constitution or policy is not science. It is morality.

Housing discrimination, racial discrimination in implementing medical care with increased morbidity and mortality of patients, these are real stats in a Navy facility overseas.