By Themistocles

Current commentators consider the combination of collisions, groundings, and senior reviews of 2017 to be a watershed event for the Surface Warfare community. Rather than a wakeup call for the community, 2017 should be viewed as a culminating point for the Surface Warfare community overall and the Surface Warfare Officer (SWO) culture in particular. Just as Napoleon’s policy objectives failed to bring Europe under his rule, despite brilliant military victories,1 many post-Cold War policy decisions for the Surface Warfare community, as admitted by past and current leadership, were misinformed. In some cases, they appear to have done more harm than good to the Surface Warfare community. More importantly, those changes in policy drove changes in the SWO culture. And, while many people debate the merits of some of those earlier policy decisions, the debate is lost in the fog and the SWO community is missing the real opportunity to reclaim its warfighting excellence by recreating the culture which led to victories within the last century in the same waters in which sailors died in 2017.

By identifying the warfighting traits the community believes necessary to lead, fight, and win at sea, by developing a modern approach to promotions and assignment processes, and by leveraging readily available techniques and solutions in use by leading industrial sectors,2 the SWO community can return to a culture built on warfighting competence and professional proficiency – excellence – that it once exemplified as it stood as the premier community in the Navy. This is no small task. But it is readily doable and doable in short order.

Leveraging Modern Techniques And Solutions To Restore SWO Warfighting Excellence

The national and global competition for talent in business, industry, and academia has driven the development of a variety of techniques and solutions to help organizations win the competition. Current techniques and solutions include compliance with federal and state job application laws, tailored machine reading, and the ability to develop specific questions or processes in an effort to find the right talent. Applicants build their profile and post or submit their resume. Depending on the traits the customer is looking for, applicants are screened. If their profile and resume are assessed to not meet the desired factors, applicants are notified by email that they are no longer needed to participate in the screening process. Or, if they score high enough, applicants may be required to participate in another level of screening in the form of a battery of questions or other online exercises – all before a single human has reviewed their submission. Of course, articles abound about how inhuman and unfair the process has become. However, more and more talent is migrating to these online processes to find employment and more and more organizations are paying for these services in order to win the competition for talent. These existing techniques and solutions could be applied to improve and align warfighting skill sets and proficiency for the SWO community.

Developing the Warfighting Trait Model

For starters, past naval heroes were not rated by the same processes used today. However, unstructured data in the form of biographies, articles, battle reports, and other sources can be processed using current cognitive processing methods to glean or extract a set of character traits common to those past naval heroes deemed to have exhibited warfighting excellence. In parallel, a cadre of junior officers, with very few select retired flag officers as advisors, can separately develop a set of warfighting traits.3 It is essential that the ideal of warfighting excellence is captured by this group. Once both sets of warfighting traits are generated, they are then synthesized into a single warfighting trait model that would exemplify an individual with premier warfighting excellence. With the ideal trait model in hand, the Surface Warfare community can then embark on “scoring” individual warfighting proficiency reflective of its officers’ performance.

Scoring Individual Warfighting Capability

Returning to warfighting excellence to reinvigorate and restore the SWO culture may necessitate a reconsideration of not only the factors by which warfighting excellence is determined but also an expansion of the data set from which those factors are pulled. The existing performance evaluation system and its fitness reports, and how they are used, do not meet the need and do not drive warfighting excellence. Fitness reports serve a purpose and can continue to serve as one source of data for an officer’s performance. However, there are a myriad of unique and high performing skills demonstrated daily in the fleet. Yet, the proficiency with which those skills are performed is not assessed or recorded. Reportedly, every landing onboard an aircraft carrier is an opportunity to rigorously and objectively score the pilot’s performance, and provide critical feedback in the performance of this critical warfighting skill. The Surface Warfare community should immediately adopt an approach similar to that used by Naval Aviation.

For example, the shiphandling skills necessary to get a ship underway may be observed or scored during the Basic Phase or periodically in a simulator, but there are dozens more special details which are not required to be scored. Similarly, ships routinely go alongside for underway replenishment, but this opportunity is lost for assessing shiphandling proficiency.

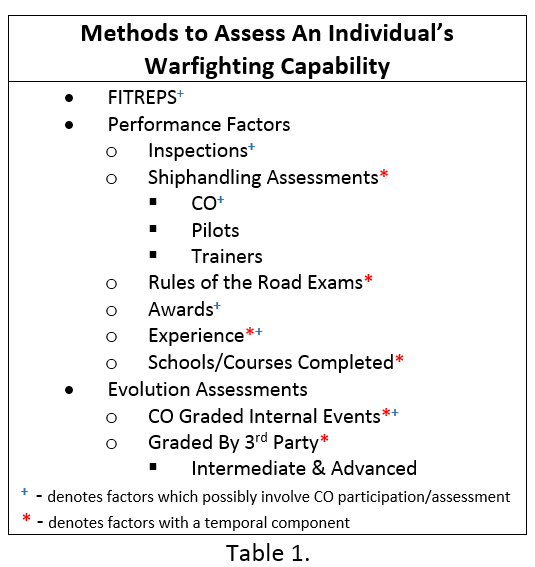

In a healthy command, the plan-brief-execute-debrief (PBED) process is alive and well, but scoring against community-wide professional standards does not exist. Establishing such standards and scoring an officer’s performance to those standards would contribute to establishing officer’s warfighting capability and proficiency scores. Table 1 lists some of the means to establish an officer’s warfighting scores.

Some aspects of the warfighting scores would necessarily have a temporal component as proficiency degrades over time, especially time spent away from the waterfront. For example, an Executive Officer (XO) who last took a ship alongside for replenishment at sea four years ago would (and should) have their warfighting capability score appropriately degraded. All things being equal, the XO who went alongside yesterday is likely to be much more proficient at that skill than the XO who went alongside four years ago.

Consider other Navy communities such as Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD), Divers, and Aviators. They all have skills that have an “expiration date.” In order to maintain proficiency and prevent triggering a requalification requirement, the skill must be demonstrated at some objectively established periodicity. While the periodicity can be lengthened such that the importance of the qualification is diminished, it must be a consistent standard to restore the warfighting excellence of the SWO community. If maintaining proficiency in basic shiphandling evolutions really is important to the SWO profession and culture, then SWOs will necessarily spend some of their shore duty in shiphandling simulators for their periodic assessments and community leadership will resource the requirement. Going to the Joint Staff for a 22-month tour will not be an excuse for not maintaining proficiency in warfighting skills.

Also listed in Table 1 are those methods that are available to and fully within the purview of a ship’s Commanding Officer (CO). This should help alleviate any concern the community might have on eroding the CO’s ability to lead or develop their wardrooms. While most of the methods are self-explanatory, it should be noted that the scores achieved during the Basic Phase are absent. Fundamentally, the Basic Phase is a training event. As such, introducing those scores into an officer’s warfighting capability score could diminish the training opportunity. In other words, activities that are primarily for training must be treated as such allowing mistakes to be made and learning to occur without concern about an officer’s warfighting capability score. Additionally, a CO’s assessment averages, just as with fitness reports, would need to be tracked as a forcing function to prevent inflating scores.

As an officer approaches a career milestone, such as a selection board or a slate, their warfighting capability score firms up and is then compared to the warfighting trait model. It is this comparison that determines their ranking within their respective cohort. For a selection board, this rank determines whether or not they are selected. Gone are the days where careers are determined by a system which is “as fair and unfair to everyone equally.” A bad briefer will not send the community’s best to “the crunch.” The Board members will know the warfighting trait model and they will be able to see the officer’s score against that model. They will see the score trends over a specific assignment and throughout the officer’s career. This way, warfighting competence and professional proficiency become the primary determinants for selection and assignment.

While most of the discussion has been focused on the determination of an individual’s warfighting capability score and proficiency, similar approaches can be used to assess shipboard teams and the ship as a whole fighting unit.

Slating For Unit Warfighting Excellence

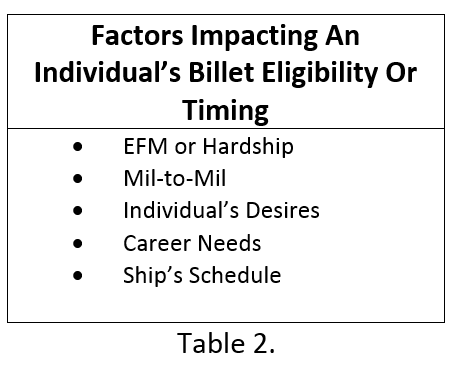

Another benefit of knowing an individual’s warfighting capability score is developing slates which better support the fleet’s warfighting readiness needs by ensuring a ship’s overall warfighting capability score remains above a minimum level through slating officers to that ship using their warfighting capability scores.4 Consider that when a group of individuals come into their slating window, their warfighting capability score is again determined. The group is then ranked and divided into top, middle, and bottom thirds (or quarters). For example, a prospective Department Head who ranks in the top quarter will get slated to a ship where the current Wardroom’s overall warfighting capability score indicates they could use some talent. Of course, there is risk that an officers’ duty preferences will not align with the fleet’s needs, but that issue exists today and will continue to require the same quality engagement by community leaders. Detailers will still need to understand factors listed in Table 2. While Table 2’s factors are important to an officer’s quality of service, they are not factors for determining warfighting excellence. By grouping a slate by quarters or thirds, flexibility is created which allows accommodating factors in Table 2. But, the entering argument for the entire officer slating process is warfighting capability and professional proficiency.

The existence of a strong, objective warfighting excellence scoring system would allow the Surface Warfare community to manage warfighting capability within individual ships and across the fleet. It will provide a means by which the performance of individual ships and the fleet can be improved.

Things to Guard Against

The process of driving the SWO culture back to warfighting excellence and professional proficiency will be challenging and there are those who will fight the change tooth-and-nail. Senior officers will see this as an attack on “their Navy.” Detailers will see this as a challenge to their primary activities. Senior mentors and advocates will see this as an affront to their mentoring and their confederation of mentees. Some will see this approach as a challenge to various support organizations external to DON, such as the Surface Navy Association. Many will immediately start looking for ways to game or manipulate the system, eroding its effectiveness. These things must be anticipated and guarded against as a new process that attempts to change culture will have to face friction posed by existing culture.

Conclusion

If SWO warfighting excellence is the reason that the Surface Warfare Community exists, and if warfighting competence and professional proficiency is the critical need for the current and future maritime warfighting environment, the SWOs must rise to the challenge. By leveraging modern techniques and solutions to develop an objective and rigorous system of assessing warfighting capability for SWOs throughout their career, and by using the warfighting capability scores to make warfighting competence and professional proficiency the centerpiece of promotion and assignment, the SWO community will realize its greatest potential and return to a level of professionalism not seen since the end of World War II.

Themistocles is a pseudonym whose choice is intentional in order to focus on the subject of the article rather than the author. There is also the parallel in the choice of Themistocles that, while some of the ideas presented may not be popular with the establishment, the discussion and discourse prompted by these ideas may again assist in establishing the preeminence of the naval power of the world’s greatest democracy. Statements and opinions expressed in this article represent personal views and not that of the DoD or DoN.

Bibliography

Weldman, Thomas. War, Clausewitz and the Trinity. New York: Routledge, 2013.

[1] Weldman, War, Clausewitz and the Trinity, 79.

[2] While there is a vibrant debate about what is and what is not ‘artificial intelligence’, ‘machine learning’, and other relatively new terms, this paper focuses on the fact that there are modern techniques and solutions available rather than attempting to define terms which are new, changing and not yet agreed upon by the wealth of experts debating them.

[3] The involvement of and control by current flag and senior naval officers in articulating this set of warfighting traits must be purposefully limited so that an independently developed set of traits can be achieved. The concern is that traits which may have contributed to the current culture will be captured inadvertently. Additionally, the flag officer advisors’ role is to guide the junior officers and constructively challenge their ideas to strengthen their product. The flag officer advisors to have no veto over or approval authority regarding the junior officers’ results.

[4] A unit’s overall warfighting excellence score has further implications in how and when they are employed by operational commanders. However, those possibilities are not discussed here in order to keep the discussion focused on improving the SWO culture.

Featured Image: Pacific Ocean (April 21, 2018) USS Stockdale (DDG 106) fires its Mark 45 Mod 4 5-inch gun during a live fire exercise as part of a Cruiser-Destroyer (CRUDES) Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training (SWATT) exercise. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Amanda A. Hayes/released)

The historical Themistocles trained his Athenian oarsmen on his Triremes before he ever went into battlle. This article offers many useful suggestions for reform onboard ships and within the process to train and certify them. What about initial training at all levels to include division officer, Dept. Head and XO/CO before they reach their ships? You cannot train well as a team member aboard a ship unless you first develop basic proficiencies. The surface navy gradually eroded those from 1990 to 2003. The failure of CBT forced a return to brick and mortar schoolhouse training, but more fundamental, initial training is needed.

Some interesting ideas here, but as I read the slating discussion I kept thinking of a “Swipe Left / Swipe Right” model where the machines present individuals who are likely to fit the bill, but the decision maker makes quick judgments based on shallow perceptions of initial appearances. That may not be the intent of what’s described, but it is an outcome we would have to anticipate.

Skip the machine grading and screening. Skilled warfighters are made, not found. Only human evaluators can determine if a particular candidate is getting properly made, or needs to find another career path.

Here’s a suggestion that would be easily implemented to improve the quality of career warfighters: stop giving them non-warfighting tours and billets. Allow each career warfighter a single shore tour to attend naval postgraduate school at the career midpoint, then any shore tours thereafter should be short (2 years or less) and focused on either training junior officers to be warfighters, or working with others to develop and refine improved warfighting systems. The 20 year career path of a career warfighter should never involve administrative or other non-warfighting focused billets. There are plenty of non-warfighters available to the Navy to do those jobs.