India’s Role in the Asia-Pacific Topic Week

By MAJ Chad M. Pillai

“As the United States and China become great power rivals, the direction in which India tilts could determine the course of geopolitics in Eurasia in the twenty-first century. India, in other words, looms as the ultimate pivot state.”

Robert D. Kaplan (The Revenge of Geography)

I remember reading these words several years ago and thinking back to my trip to India in 1998 at the height of the nuclear testing crisis by India and Pakistan. During that trip, I took the opportunity to interview several Indian scholars on India’s ascent as a nuclear power and its implications. Those interviews produce two key themes: (1) India’s nuclear weapons program was designed as a deterrent to China, not Pakistan as many claimed, since China went nuclear in the 1950s and fought a border war with India in 1962; and (2) a disbelief of U.S. relations with an Islamic military dictatorship in Pakistan and Communist China at the expense of the world’s largest democracy.[1] In order to accept these two observations, especially if India becomes the strategic pivot nation, the U.S. must acknowledge India’s relationship with, as Seth Cropsey described in his New American Grand Strategy article, the triple hegemonic threats in the Eurasian landmass: Iran, Russia, and China.

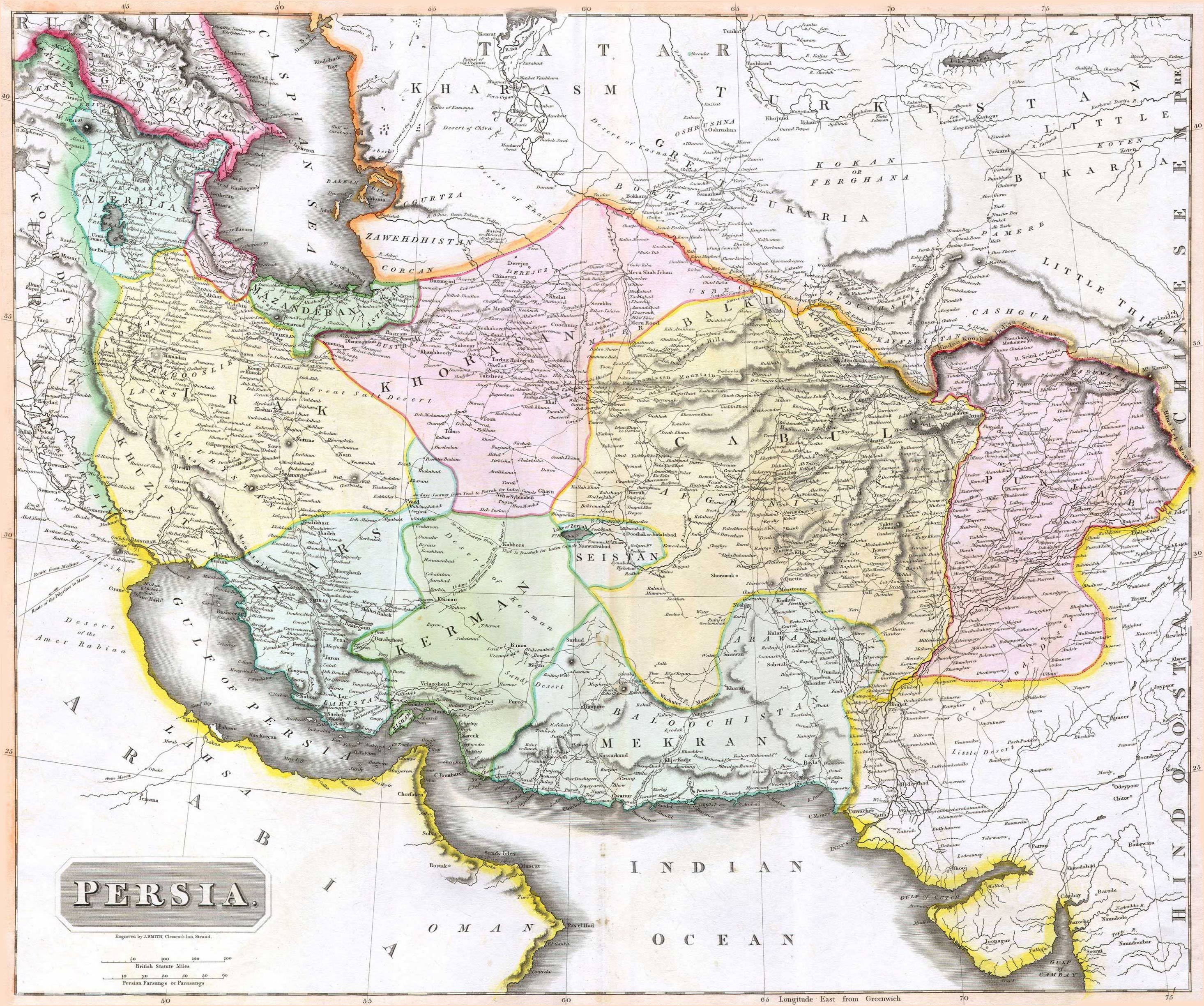

India and Iran’s relationship dates thousands of years from when the ancient Persian Empires and Indian Empires ruled the territories from Mesopotamia to the tip of India – occasional rivals during the period of the Indian Mughal (Sunni) Empire. Modern day Afghanistan served as the buffer zone and trade route between these two civilizations. During the period of the of Colonial British-Russian Rivalry (The Great Game), the landmass between the Persians and British India served as a strategic buffer, and later provided the foundation for India’s relationship with Russia after “The Partition of 1947” that split India and Pakistan.[2]

India’s relationship with Russia dates to the Cold War after it gained independence from the United Kingdom. Initially, India was a champion of the “Non-Aligned Movement” seeking not to get entangled between the two superpowers. The decline in U.S.-Indian relations during the Johnson administration pushed India into the Soviet sphere due to differences regarding the Vietnam War, India’s stance on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), Indo-Pakistani tensions, and economic underperformance. The U.S. military relationship with Pakistan further alienated India which required India to invest heavily in Soviet armaments. India’s and Russia’s relationship has continued despite the end of the Cold War, primarily in foreign military sales and development (ex. Co-Russian and Indian joint Stealth Fighter venture).

India has expanded military relations with the United States as it sees China as a growing security challenge. Additionally, Indians prefer their cultural (Bollywood and Hollywood) and linguistic (large Indian English speaking population) similarities to the United States.[3] In fact, C. Raja Mohan wrote a statement in his book Crossing the Rubicon by then External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh issued ahead of President Clinton’s visit of ‘five wasted decades’ and his “reflection on the fact that the world’s two great democracies found it impossible to engage in any substantive cooperation-either economic or political in the country’s first fifty years.”

As the two most populous nations on earth, the unique and recent strategic rivalry between India and China, as Robert Kaplan stated, has no history behind it. They are two ancient civilizations separated by the Himalayan Mountain range that traded, passed religious and cultural knowledge back and forth in the peripheral zones (Afghan region of the Silk and Spice Route and South East Asia where we see a mixed Indian-Chinese influence among populations, linguistics, and cuisine), but have no known history of major warfare between the two save for brief conflict in 1962. What is driving the emerging competition between India and China is their re-emergence on top of the global economy. As Robyn Meredith states in her book The Elephant and the Dragon: The Rise of India and China and What it Means for All of Us that “after a centurylong hiatus, India and China are moving back toward their historic equilibrium in the global economy, and that this is producing tectonic shifts in economics as well as in geopolitics.” It is projected that India’s population will exceed China’s and both will continue to modernize and create ever greater demand for consumer goods to meet the needs and desires of their vast populations. As a result, the Achilles Heel and source of emerging friction is the need to secure access to energy from Central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa to fuel their economic growth.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), “China is the world’s second-largest consumer of oil and moved from second-largest net importer of oil to the largest in 2014.” Meanwhile, “India was the fourth-largest consumer of crude oil and petroleum products in the world in 2013, after the United States, China, and Japan. The country depends heavily on imported crude oil, mostly from the Middle East.” While much has been written of China’s activities in Africa to secure energy and mineral rights, less has been shared about India’s competition, though less successful, in the same arena. A significant lag in its competitiveness is China’s reliance on state-owned enterprises that offer better terms due to government guarantee vs. India’s reliance on its private sector and smaller state owned enterprises. Despite this, India has also been working with Central Asian States and Iran to develop the proposed Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline and the Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline with recent Indian investment ventures in Iranian oil and gas fields in the range of $20 billion. To offset the competition for energy, both countries have invested heavily in renewable energy resources such as wind and solar.

India’s strategic geography provides it a long-term competitive advantage over China due to its position between the world’s key energy chokepoints. According to the IEA World Oil Transit Chokepoints Report, “world chokepoints for maritime transit of oil are a critical part of global energy security. About 63% of the world’s oil production moves on maritime routes. The Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca are the world’s most important strategic chokepoints by volume of oil transit.” India’s strategic relationship with Iran and South East Asian nations such as Malaysia and Indonesia, along with its control of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, place it in a formidable position to disrupt China’s access to its energy markets in the Middle East and Africa. China has been trying to offset its ‘Malacca Dilemma” by establishing economic-security ventures known as its “String of Pearls” to include expanded ventures with Pakistan, Burma, and Sri Lanka.

The ‘Malacca Dilemma’ and ‘String of Pearls” will drive each nation to invest in their missile arsenal (nuclear and non-nuclear), naval power, and airpower. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Military Balance 2016, China accounts for 41% and India for 13.5% of all defense spending in Asia. Further comparisons between the two show China spent $145 Billion (US Dollars) vs. India’s $47 Billion (US Dollars) in 2015. Analyzing their naval power, China has the edge in numbers with more submarines (61 = 4 SSBNs and 57 SSNs), more combatant ships (74 including one carrier), and mine warfare (49). India currently fields a navy with 14 submarines, 28 combatant (two carriers to China’s one), and 6 mine warfare ships. However, its ability to influence the Strait of Malacca provides India the competitive advantage, especially if its efforts are combined with U.S., Australian, Japanese, and coalition nations to offset China’s numerical superiority. Additionally, China will face its own A2/AD threat environment in the India Ocean as India expands its medium and long range missiles.

As the United States increasingly faces challenges to its global power by Iran, Russia, and China, its relationship with India will grow in strategic importance. While India may never become a true ally of the U.S. due to its strategic relations with the other three powers, its role as a strategic pivot or fulcrum can provide a source of stability and balance. Its democratic and cultural values align it with the United States and the West, but geography and history place India squarely within the context of its Eurasian neighbors.

MAJ Chad M. Pillai is a U.S. Army Strategist. He has published articles and blogs in Military Review, Small Wars Journal, Infinity Journal, The Strategy Bridge, Offizier, War on the Rocks, and CIMSEC. He received his Masters in International Public Policy from the Johns Hopkins University School for Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in 2009. This article was influenced by his Asian Energy Security and South Asian International Relations courses at SAIS.

[1] In 1998, I took a trip to India for my adopted father’s mother’s death that coincided with the nuclear testing. As a result, I proposed an extra credit project for my ROTC instructor to study the security implications and worked on it further during my internship at the Department of State that summer semester.

[2] The strategic implications of the 1947 Partition continue in today’s conflict in Afghanistan as Pakistan views India’s relationship with the Afghan Government with suspicion and fears Indian encirclement if it loses its strategic maneuver space among the Afghan Pashtu regions. Recommend “The Great Defile” by Diana Preston to learn more of the British Indian (manned primarily by Punjabis – Modern Pakistanis) Army’s misadventures during the Afghan Wars of 1838-1842.

[3] Indians prefer to study in the United States and migrate. One current state governor and one former state governor are of Indian descent.

Featured Image: Prime Minister Modi speaks from the Red Fort in New Delhi on India’s 69th Independence Day in 2015.

India is not a country with sustainable military capacity. India has too many political and social dogmas that are eroding their capacity as an economic power as well as a military one. They are effectively a blunt sword and need serious internal improvements before US even bothers with them as a partner. You cannot manage a military while your officials are so horribly corrupt, self-serving and reactive. Unless change occurs, its a very messy house of cards that India sits on.