India’s Role in the Asia-Pacific Topic Week

By David Scott

India and the People’s Republic of China are encountering each other across the Indo-Pacific, the predominantly maritime region spanning the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Harsh Pant’s prognosis in March 2016 is persuasive that “the turf war between the two navies, as both nations seek greater roles in regional [Indo-Pacific] dynamics, is set to grow.” Both countries are developing blue water long distance naval capabilities, and adopting Mahanian-style seapower strategies for power projection. Implicit competition in what has been dubbed “a new great game for influence in the Indo-Pacific” between these two rising powers is the order of the day in the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea, the West Pacific, and the South Pacific.

Indian Ocean

India has long held an implicit view of natural regional preeminence, based on its central geographical location in the Indian Ocean, whereby the Indian Ocean should somehow be India’s Ocean, which was the title of David Brewster’s book, complete with the subtitle The Story of India’s Bid for Regional Leadership. The challenge, or “wake up call” (Kapila), for India is China’s increasing Indian Ocean presence on the military, diplomatic, and economic fronts. Militarily this is shown through the deployment of the Chinese navy into the Indian Ocean. Diplomatically this is shown through China’s pursuit of littoral states and its “cheque book diplomacy” among the micro-island states of the Indian Ocean basin. Economically this is shown through China’s recent Maritime Silk Road (MSR) initiative which it has pushed since November 2014.

These events have generated widespread fears for India of a so-called string of pearls drive by China, denied of course by Beijing, to establish staging posts across the Indian Ocean. Pakistan’s port of Gwadar, now being run by the China Overseas Ports Holding Company Ltd (COPHCL), is one key irritant for India, as it provides a potential deep water berth for the Chinese navy. This growing Chinese presence across the Indian Ocean feeds into that other India strategic fear of encirclement, by a hostile China along its disputed northern border, ensconced in an equally hostile proxy state to its West in Pakistan, penetrating neighbours like Nepal, (previously) Myanmar, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and deploying naval forces to its South. India’s counter has been multi-pronged: building up the Iranian port of Chabahar as a “checkmate” (Sakhuja) to China building up Gwadar, strengthening its own outreach to South Asian neighbours, strengthening its own outreach to Indian Ocean island states, pushing its own naval presence, and keeping China out of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS). Of further significance are India’s bilateral MALABAR exercises with the US operating in the Indian Ocean since the mid-1990s, which also included Australia and Japan in 2007, and which again also involved Japan in 2015 and 2016. These are indeed “aimed at countering growing Chinese military presence in the Indian Ocean” (Singh 2015), with China denouncing them as dangerous (Global Times). What can be called India’s maritime-led “counter-containment” (Rehman) of China can be seen elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific, through what has been dubbed India’s own necklace of diamonds network of maritime-centred security partnerships.

South China Sea

The next part of the Indo-Pacific where India and China come up against each other is in the South China Sea, where India’s Act East policy “meets” (Chang) China’s southern drive. Whereas the Indian Ocean is India’s strategic backyard into which China is coming, the situation is reversed in the South China Sea which is China’s strategic backyard into which India is coming. The key feature here is that most of the sea is claimed as Chinese, supposedly from “time immemorial,”under China’s 9-dash line which encloses around 80% of the waters and includes the two groups of the Paracels and Spratly islands. The Paracels remain in dispute between China and Vietnam. The Spratlys (which mostly consist of atolls, rocks and reefs rather than proper “islands” as defined under UNCLOS criteria) remain in dispute between China (Beijing and Taiwan), Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei (waters) and Indonesia (waters).

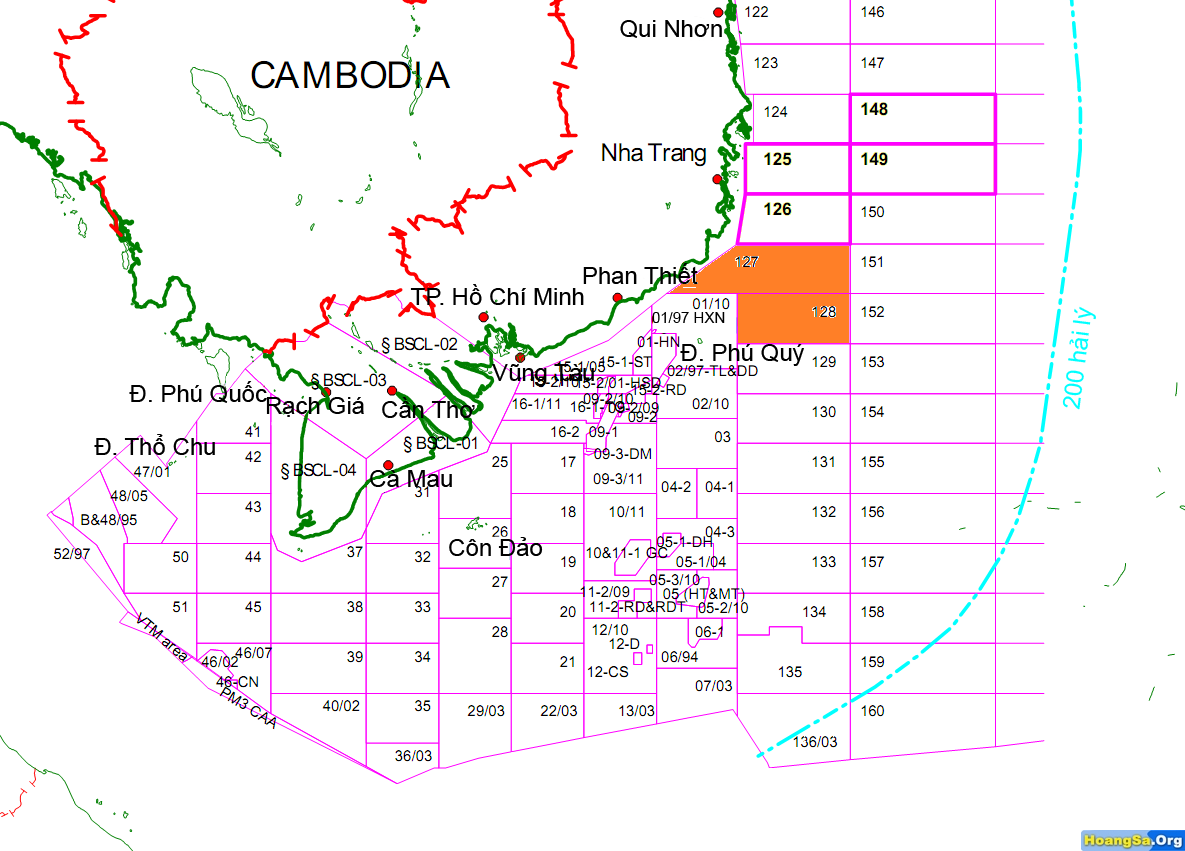

The South China Sea serves as India’s “maritime gateway to the Pacific” (Chaturvedy). While it has avoided taking any stance on sovereignty issues, India’s response to China’s increasingly assertive push in these waters has been six-fold. Firstly India continues to reiterate its support for adherence to international law and to open transit in regional forums like the ASEAN Regional Forum and East Asia Summit (EAS). This has been an implicit criticism of China. Secondly, India has pushed this line on the South China Sea in bilateral security discussions with the US, Japan, and Australia, and also in the India-US-Japan and the India-Japan-Australia trilateral mechanisms set up in 2011 and 2016 respectively. China has rejected all such discussions as outside interference. Thirdly, India has reinforced security ties with the Philippines and above all with Vietnam. Although there is official denial by India that such security strengthening is related to China, in reality it represents a degree of tacit balancing by India and these partners with China in mind. India’s strengthening security links with Vietnam continue to have a strong maritime flavour as India has provided supplies to the Vietnamese navy and Vietnam has provided berthing facilities for India at Cam Ranh Bay. The logic here is a Vietnam card being played against China by India to match the Pakistan card playable against India by China. Fourthly, since 2011, India has signed agreements with Vietnam whereby India’s national state company Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) has conducted explorations in various waters within the South China Sea controlled by Vietnam as well as waters such as Block 128 that are also claimed by China. This has attracted vociferous Chinese denunciations. Fifthly, India has carried out joint SIMBEX exercises in the South China Sea with Singapore on a biannual basis since 2005. Sixthly, the Indian navy has been deploying regularly into the South China Sea since 2000. All of these aspects of growing Indian presence in the South China Sea can be seen as a response to growing Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean. India may not be able to stop this growing Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean, but it can apply countervailing pressure through going into China’s own backyard.

West Pacific

China views the West Pacific through the prism of what it calls the “first island chain” (diyi daolian) running from Japan, the Ryukyu chain, Taiwan and the Philippines; and the “second island chain” (dier daolian) running down from Japan, the Bonin islands, the Mariana islands, and the US stronghold of Guam. Chinese maritime doctrine aims to achieve penetration of the first island chain and ultimately the second island chain. Deployment of the Chinese navy beyond the first island chain into the West Pacific has become an increasingly common occurrence since 2004, and is of rising concern to Japan and the US, who have sought out India as a fellow security partner.

With regard to India, a key feature is that the Indian navy has also been deploying into the West Pacific since 2007, “to counter China” (Joseph). Particularly significant have been bilateral naval exercises carried out in the Western Pacific by India with the US in 2007 and 2011, the bilateral naval exercise with Japan in JIMEX 2014, and the trilateral naval exercises with the US and Japan in 2009, 2014, and 2016. It is officially denied that such exercises are aimed at China, but in reality they represent another tacit degree of balancing.

South Pacific

Beijing’s initial interest in the South Pacific is competition with Taiwan for diplomatic recognition as the legitimate government of China, in which a “cheque book diplomacy” war has been in operation for the past few decades. The Pacific islands’ vast Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) also offer lucrative fishing grounds for deep sea fishing and seabed mineral resources. These waters are very distant for regular Chinese naval operations, although headlines were made when two Chinese warships visited Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, and Tonga in September 2010.

India is involved in a catch-up operation in the South Pacific, in part to “counter” (Ganapathy) China’s earlier established presence. China has been a Dialogue Partner with the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) since 1989, while India has been one since 2003. China set up the China-Pacific Islands Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum (CPICEDCF) in 2006, while India set up its Forum for India-Pacific Islands Cooperation (FIPIC) in 2014. Narendra Modi’s visit to Fiji in November 2014 was not only predated by Wen Jiabao’s visit in 2006, but was also immediately followed by President Xi Jinping’s own visit three days later. China enjoyed satellite tracking facilities at Kiribati from 1997-2008, which served a dual purpose of enabling spying on the American missile range at Kwajalein atoll in the Marshall Islands, some 600 miles away, while India more recently announced in 2015 that it was setting up a space research and satellite monitoring station in Fiji.

Conclusions

So far the China-India picture is one of competition, rather on the lines of the 2012 book by Raja Mohan entitled Samudra Manthan: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Indo–Pacific. Are there any signs of cooperation? Not very much it would seem in the Indo-Pacific. India and China are both members of de facto Indo-Pacific bodies like the ASEAN Regional Forum and the East Asia Summit. However, in these venues India had generally expressed similar, though more obliquely expressed, concerns about Chinese policies in the South China Sea alongside Japan, Australia, and the United States.

There are some signs of China-India cooperation at the global level. Both states seek a multipolar international order, both powers seek reform of hitherto Western-dominated international institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, and both states have a similar environmental stance, of “differentiated responsibilities” on international obligations. However, competition is more evident at the regional level. Admittedly there is some convergence in the anti-piracy operations that both countries, along with others, have been carrying out in the Gulf of Aden since 2011. However, India is generally more concerned about Chinese intentions across the Indo-Pacific and about being encircled by China. In turn, China’s own continuing “anti-encirclement struggle” (Garver) remains fraught in light of ever strengthening Indian security links across the Indo-Pacific with Australia, Vietnam, Japan, and the US in particular.

It is true that direct bilateral maritime discussions started between India and China in the shape of their Maritime Dialogue mechanism, which met for the first time in February 2016. However, with little recorded about the actual discussions there, let alone absence of tangible agreements on anything, this remains a mechanism still to prove itself in the long term as anything more than a diplomatic sop. Meanwhile ongoing Indo-Pacific maritime friction between China and India remains more probable in the short to medium term.

David Scott is an ongoing consultant-analyst and prolific writer on India and China foreign policy, having retired from teaching at Brunel University in 2015. He can be contacted at davidscott366@outlook.com.