This article originally featured on The Bridge and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Aaron Bazin

Strategic thinking can happen almost anywhere: in a conference room, a university lecture hall, or in the dark basement of a military headquarters. If you think about it, really anyone can do it, from a president to an Army private, from a subject matter expert to an armchair general. Although anyone can do it at any time and in any place, doing it well is neither easy nor is it commonplace.

anywhere: in a conference room, a university lecture hall, or in the dark basement of a military headquarters. If you think about it, really anyone can do it, from a president to an Army private, from a subject matter expert to an armchair general. Although anyone can do it at any time and in any place, doing it well is neither easy nor is it commonplace.

A variety of research projects have sought to uncover what it means to think strategically in the military context. In general, strategic thinkers act primarily in one of four roles: leader, advisor, practitioner, or planner. To function effectively in these roles require the skills of information gathering, learning, critical thinking, creative thinking, thinking in time, and systems thinking. Building upon these ideas, the purpose of this article is to explore some of the timeless questions that strategic thinkers can ask to help themselves and others think clearly about issues of strategic significance.

WHAT ARE THE FACTS, ASSUMPTIONS, AND LIMITATIONS?

This question is so basic it is often forgotten or glossed over, but asking it is absolutely essential. In a strategic context, there are a tremendous number of facts to consider. The key is to identify the ones that really matter the most without going too far and reaching the point of paralysis by analysis. As for assumptions, if never surfaced and debated they represent a sizable gap in one’s logic. Many failures at the strategic level are due to people insufficiently discussing assumptions, or worse, dismissing them outright. One recent example that highlights the importance of good assumptions is when decision makers assumed that the troops that invaded Iraq in 2003 would be “greeted as liberators.”

While strategic thinkers always should try to think in an unconstrained manner, there always exist some physical, logistical, moral, or financial limits to what is possible. Failure to understand the parameters and limits of a strategic approach has led to many military overextensions throughout history (e.g., Napoleon in Russia, Soviet Union in Afghanistan, etc.). Much like the enemy, the real world always gets a vote. Understanding the limiting factors and developing a common understanding of the problem are supporting activities, which leads to the next question.

WHAT IS THE STRATEGIC PROBLEM AND DOES IT PRESENT ANY OPPORTUNITIES?

Uncovering a problem statement is also essential, but often overlooked. Many strategic thinkers immediately dive in and start describing what must be done. In a fast-paced environment, it can be very tempting to do this, but it should be avoided. Fundamentally, if you do not pause and take the time to identify the problem you are trying to solve, how can you ever hope to solve it?

One of the easiest and most effective ways to develop a problem statement is to spot the gap between the current conditions and the desired conditions (the “want-got” gap). What is almost magical about developing a problem statement is that if you get it about right, the answer should begin to reveal itself, even in the most difficult of situations. Of course, most strategic problems are complex or wicked and change over time. Therefore, it is important for the strategic thinker to not only ask this question early, but also ask it again and again as the strategic problem unfolds.

By their nature, military thinkers often tend to think about negative, worse–case scenarios and outcomes. To take a more optimistic approach, one may find it valuable to look for opportunities as well as problems. The idea here is this: if one can seize small opportunities over time, this can build irreversible momentum and eventually bring about positive change. Overall, this question helps focus time, effort, and resources in a coherent, positive, singular direction.

WHAT ENDURING INTERESTS ARE AT PLAY?

Many strategic thinkers seek to implement parrot the latest policy position they heard without fully thinking about the inherent interests at play. Some argue that interests such as prosperity, values, security, and legitimacy, will always be important despite which direction the political winds are blowing. The strategic thinker should try to understand how the political intent is tied to the enduring interests that will remain long after a political position has changed. This question helps one put the problem in context and reflect upon the deeper strategic meaning behind the problem and its possible solutions.

IN THE PAST, WHICH STRATEGIES WORKED, WHICH DIDN’T, AND WHY?

The lessons of the past are always there to school the strategic thinker if they are willing to listen. Of course, events will rarely unfold exactly the same way twice, but there are often important echoes from the past to be heard in the present. This question suggests that strategists would be well served by looking for practical advice from history and tying those lessons to prudent courses of action in the present. Neustadt and May’s Thinking in Time describes even more questions that help the strategic thinker make the most effective use of history. The benefits of this question are that it helps one reflect upon the past and generate possible options on what can be done today.

WHAT ARE THE OPTIONS (AND WHICH ONE IS THE LEAST WORST)?

In the past, policy makers may have been satisfied with being presented between one and three courses of action. Today, many policy makers demand strategic advice as a menu of options, where they can pick and choose what to implement and when to implement it. In these cases, the strategic thinker has to think divergently and come up with as many options as possible. As strategic problems rarely have solely military solutions, strategic thinkers should have the ability to develop options that include elements of national power beyond just the “M” in the Diplomatic, Informational, Military, and Economic (DIME) model. Of course, with wicked problems, there are often no good options, just a series of progressively bad ones.

HOW DOES THIS ALL END?

It is easy for a strategic thinker to become so engrossed with the minutiae of the problem that they can lose sight of their goal. Perhaps, at times, the goal shifts and the previously agreed upon destination is now a fool’s errand. That is why this question is so important. The strategic thinker must have the ability to take a break from the crisis of the day and take the long view. Because there is often so much uncertainty surrounding strategic problems, reflecting on the end state is often difficult. However, if you do not know where you really want to go, any road will take you there.

IS THIS WORKING?

When a policy is approved or a plan is signed, the thoughts captured on the document are frozen in time and begin their rapid descent into irrelevancy. This is a natural progression where a key concept’s idea is game-changing today, much less so in six-months, and barely remembered a year later. The key here for the strategic thinker is to not rest too much and remain in a state of continual assessment and advocate appropriate change as events unfold. As strategic problems are usually both quantitative and qualitative in nature, keeping an open mind to all types and sources of information is prudent.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Even the best strategic ideas are subject to failure if the follow through is lackluster, therefore, it is important to always ask what happens next. Every strategic choice comes with some degree of risk. These risks should be understood and, if possible, mitigated. In addition, with complex problems many issues remain unseen, and there is always the possibility of unintended consequences. Many strategic shortcomings are the result of taking prudent action in the present that results in future blowback that was unforeseen at the time. An excellent example is the lack of U.S. follow through in Afghanistan following the withdrawal of the Soviet Union, popularized in the movie, Charlie Wilson’s War.

CONCLUSION

The level of responsibility placed on the shoulders of a strategic thinker can be daunting. The ability to think clearly is difficult in situations where time is of the essence, lives are on the line, or billions of dollars are on the table. It is precisely because of the high-stakes that good strategic thinkers need to ask good questions to uncover good answers. Of course, there are many questions that strategic thinkers should ask and this list is simply one starting point. In the end, the quality of one’s strategic thought will be directly proportional to the time and effort they put into the endeavor, no more and no less.

Aaron Bazin is career Army officer with over 20 years of leadership and experience at the combatant command level, NATO, and the institutional Army. Aaron was the lead-planner for four numbered contingency plans between 2009 and 2012, and has operational experience in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, and UAE. He is the author of the new book, Think: Tools to Build Your Mind. The views expressed in this article are the authors and do not represent the views of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

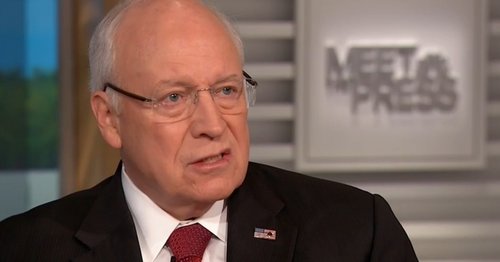

Featured Image: A reporter raises his hand to ask a question as US Army Gen. Ray Odierno, Commander of US Forces-Iraq, delivers an operational update on the state of affairs in Iraq during a press briefing at the Pentagon, 4 June 2010. (Cherie Cullen/DoD Photo)

Enjoyed the article and shared on Linkedin and Flipboard like many of your posts.

Other instances of failure in Strategic Thinking:

Jimmy Carter’s withdrawal of support for Shah of Iran.

Destabilisation of Libya by President Obama and SoS Clinton.

Dismissal of ISIS as “JV” by most of the World.

Only thing missing is some variation of “why are we here” or “what’s our objective.”