By James E. Fanell and Ryan D. Martinson

From Newport to New Delhi, a tremendous effort is currently underway to document and analyze China’s pursuit of maritime power. Led by experts in think tanks and academia, this enterprise has produced a rich body of scholarship in a very short period of time. However, even at its very best, this research is incomplete—for it rests on a gross ignorance of Chinese activities at sea.

This ignorance cannot be faulted. The movements of Chinese naval, coast guard, and militia forces are generally kept secret, and the vast emptiness of the ocean means that much of what takes place there goes unseen. Observers can only be expected to seek answers from the data that is available.

The U.S. Navy exists to know the answers to these secrets, to track human behavior on, above, and below the sea. While military and civilian leaders will always remain its first patron, there is much that USN intelligence can and should do to provide the raw materials needed for open source researchers to more fully grasp the nature of China’s nautical ambitions. Doing so would not only improve the quality of scholarship and elevate the public debate, it would also go a long way to help frustrate China’s current—and, to date, unanswered—strategy of quiet expansion. Most importantly, sharing information about the movements and activities of Chinese forces could be done without compromising the secrecy of the sources and methods used to collect it.

The Constellations are Visible…

The basic story of China’s maritime aggrandizement is printed in black and white, no need to read tea leaves. There exists a public life in China, even if highly circumscribed. Chinese journalists are paid to write articles that satisfy the urges of an inquisitive and patriotic public. Chinese scholars spend careers trying to understand the intentions and capabilities of their own country—like academics elsewhere, they banter back and forth in defense of “truth,” and bruised egos. Government agencies release reports that catalog their achievements, outline key objectives, and mobilize their personnel for the new tasks at hand. The Chinese military, communicating through service publications, seeks to inculcate a collective consciousness of what it does and why it does it. All of these sources are open to the foreign observer.

The available information provides important clues about the nature and extent of Chinese activities at sea. This is true for all three of the sea services: the coast guard, the maritime militia, and the PLA Navy.

The movements of the Chinese coast guard are particularly amenable to open source analysis. China does not operate a single maritime law enforcement agency analogous to the United States Coast Guard. It instead funds several different civilian agencies, each with a different mission. Prior to the creation of the China Coast Guard in 2013, the agencies most active along China’s maritime frontier were China Marine Surveillance (CMS) and Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE). Both agencies released surprising amounts of information through official newspapers, annual reports and yearbooks, and other channels.

These sources include significant quantitative data. For instance, it is possible to track the expansion of CMS presence in disputed waters that started in 2006. In that year, CMS began to regularize its sovereignty—or “rights protection”—patrols, first in the East China Sea, then in the Yellow Sea and South China Sea. Each year, the State Oceanic Administration (SOA) published data on these operations. In 2008, CMS conducted a total of 113 sovereignty patrols. These missions, which covered more than 212,000 nm, established CMS presence in all of the waters over which China claims jurisdiction. Four years later, in 2012, the service conducted 172 sovereignty patrols (>170,000 nm) just in the South China Sea alone.

Qualitative data also abounds. Before 2014, both CMS and FLE regularly invited Chinese journalists aboard ships operating in disputed areas. These civilian scribes chronicled China’s campaign to reclaim “lost” land and sea. While primarily designed to inspire and titillate Chinese audiences, their work provides excellent source materials for the foreign observer. For instance the eight-part Chinese television documentary that aired in late 2013 showed extensive footage of CMS and FLE ships operating in the South China Sea, including during hostile encounters with Indonesian and Vietnamese mariners.

Chinese sources also provide raw materials for understanding the activities of the second major instrument of Chinese sea power—the maritime militia. This force is comprised of civilians trained to serve military and other state functions. In peacetime, a segment of the militia, mostly fishermen, constitutes an important tool in Chinese maritime strategy. It sails to disputed waters to demonstrate Chinese sovereignty and justify the presence of the Chinese coast guard and navy. The militia also harasses foreign vessels, and helps protect China’s own.

China’s maritime militia is particularly active in the South China Sea. The Chinese press eagerly covers their activities in disputed waters, often revealing ship pennant numbers and the names of key militiamen. Websites owned by provincial, municipal, and county governments also highlight their local contributions to the “people’s war” at sea. Using such sources, Conor Kennedy and Andrew Erickson have tracked the militia’s activities at places such as Mischief Reef and Scarborough Shoal, and deciphered its role in pivotal events such as the 2009 assault on the USNS Impeccable.

The PLA Navy also releases information about where, when, and how it is operating. Air, surface, and undersea deployments are called “combat readiness patrols” (zhanbei xunluo). Service publications regularly report on these patrols—including, perhaps surprisingly, those conducted by China’s “silent service.” For instance, one October 2014 article in People’s Navy recounts a story of Song Shouju, a submarine skipper from the PLA Navy South Sea Fleet (SSF), whose diesel electric boat was prosecuted by a foreign maritime patrol aircraft and a surveillance vessel during one combat readiness patrol. According to Song, his boat was subjected to 80 hours of active sonar, placing him on the horns of a dilemma. If he surfaced, it would mean a mission failure and “put Chinese diplomacy in an awkward position” (suggesting the submarine was not operating where it should have been). But if he remained below, the boat would risk the consequences of depleting its battery. In the end, the captain decided to stay submerged until the threat had passed, which it ultimately did.1

The PLA Navy is particularly forthcoming about patrols taking place beyond the “first island chain.” These are regularly reported in the Chinese press, both in English and Chinese. In May 2016, for example, six vessels from the SSF—including three destroyers, two frigates, and an auxiliary—completed a 23-day training mission that took them through the South China, the Indian Ocean, and the western Pacific by means of the Sunda Strait, Lombok Strait, Makassar Strait, and the Bashi Channel. At least one Chinese journalist was onboard to cover the 8,000 nm voyage. Again, the available data is not limited to the movements of surface combatants. For instance, a January 2014 People’s Navy article revealed that since 2009, 10 submarines and 17 aircraft from the ESF had traversed the first island chain to conduct “far seas” operations.2 Sources like these have enabled foreign researchers such as Christopher Sharman to trace the connection between Chinese actions and its declared naval strategy.

To follow Chinese activities at sea, one need not rely on Chinese sources alone. Foreign governments also sometimes release data. Often this information is associated with a particular incident. For instance, in mid-2014, the Vietnamese press published numerous articles in English covering China’s provocative deployment of an advanced new drilling rig (HYSY-981) in disputed waters south of the Paracel Islands. More recently, Indonesia released useful information about its response to illegal Chinese fishing and coast guard activities taking place near Natuna Island.

For its part, Japan systematically issues data on Chinese presence in the waters adjacent to the Senkaku Islands. Graphical depictions of these data vividly show Chinese expansion over time, from the inaugural intrusion of two CMS vessels in December 2008 to the regular patrols that started in September 2012 and continue today. Indeed, the quality and consistency of this data has enabled foreign analysts to use quantitative methods to test theories about shifts in Chinese diplomacy.

…But Darkness Still Prevails

The information described above, while useful, nevertheless presents many problems. This is true even in the case of data on Chinese coast guard operations, which are easily the richest available to the open source researcher. A “rights protection” patrol can mean anything from a two-day sweep of the Gulf of Tonkin to a several-month mission to the southern reaches of the Spratly Archipelago. Thus, while the available data unmistakably capture the broad trends of Chinese expansion, they lack the fidelity needed for closer examination of deployment patterns. With the creation of the China Coast Guard, all this is now moot. The Chinese government no longer publishes such data, and Chinese journalists are now seldom allowed aboard ships sailing to disputed waters.

The problem is much worse in the case of the maritime militia. No Chinese agency or department systematically tracks and releases information on militia activities. Because only a portion of fishermen are members of the militia, fishing industry data is a poor proxy. Thus, there is no way to scientifically track the activities of irregular forces operating along China’s maritime frontier. We generally only learn about particular incidents, remaining largely ignorant of the context in which they take place.

Consistent data on PLA Navy activities in disputed and sensitive waters is simply not available. We do know that in recent years the service “normalized” (changtaihua) its presence in the Spratly Archipelago, but Chinese sources provide no definition of what that term means. Thus, while it is clear that the PLA Navy has augmented its surface ship patrols to these waters, we have no means to gauge the scale of that augmentation.3 In the East China Sea, Chinese sources do speak candidly about hostile encounters with the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force. However, the open source researcher has few options for gauging the extent of PLA Navy presence east of the equidistant line.

There is a more fundamental problem that must be reckoned with: in most cases, the foreign observer often lacks the means to validate deployment data found in Chinese sources. Ultimately, one must take the word of the Chinese government, which naturally considers political factors—both internal and external—when issuing such content. Information released by other governments can be valuable, but foreign statesmen have their own motives. Sometimes they seek to downplay differences. For example, it is likely that for many years China and at least some Southeast Asian states had a tacit agreement not to publicize incidents at sea.

In sum, the available open source data can account for only a tiny fraction of what Chinese maritime forces are doing at sea. Moreover, the validity of information that is available must be seen as suspect. This is where naval intelligence can help.

Sharing the Spotlight

Naturally, U.S. naval intelligence professionals, particularly those in the Pacific, pay close attention to the comings and goings of Chinese maritime forces. To this end, they employ a wide variety of sources, from highly sensitive national technical means to visual sightings made by U.S. and allied forces at sea. They also optimize other resources of the U.S. intelligence community to support their mission requirements.4 Suffice it to say, the naval intelligence community is well aware of the disposition of China’s naval, coast guard, and militia forces.

The foundation of this effort is the Pacific Fleet Intelligence Federation (PFIF), established in September 2013 by then United States Pacific Fleet Commander, Admiral Cecil Haney. The PFIF “provides direction for the organization and collaboration of the Pacific Fleet’s intelligence and cryptologic resources to support the maritime Operational Intelligence (OPINTEL) mission” of “tracking adversary ships, submarines and aircraft at sea.” It represents a level of focus and systematization not seen since the Cold War.

The PFIF is a true collaborative enterprise, involving “coordination from Sailors across multiple organizations at various echelons, afloat and ashore, working in unison 24 hours a day, seven days a week providing the most precise maritime OPINTEL to our afloat forces.”5 Efforts are “federated” across nodes in Japan, Hawaii, San Diego, and Washington D.C.6 Relevant data collected by regional allies are also included. The result is the adversary Common Operational Picture (RED COP). Through RED COP, the PFIF provides Fleet Commanders and deployed forces precise geo-coordinate level intelligence regarding the location of maritime platforms across the Pacific Fleet area of responsibility. It also contains a detailed pedigree of the sources used to identify the location of an adversary unit.

How might the USN translate RED COP into information that is valuable to the public yet does not risk sources and methods? The answer lies in the format of the transmitted product. While American forces require the detailed information contained in the RED COP, the U.S. public does not. Therefore, the USN could issue a standardized series of PowerPoint graphics that contain generic depictions of PRC maritime force disposition across the Indo-Pacific region, if not the rest of the world. Since the technology used today by PFIF watch-standers can automatically produce this type of graphic, this would involve no new burden for naval intelligence professionals.

Some may argue that placing an adversary unit in a location where there is no “plausible deniability” could expose a source or method of intelligence collection. Four factors eliminate this risk. First, the generic placement of an adversary platform on a PowerPoint graphic would, by definition, not contain the level of fidelity required to determine the source of the contact. Second, as mentioned above, nearly all locations of maritime forces at sea are derived from multiple sources. This fact further complicates the task of determining any one particular source. Third, generic graphics would be published monthly, or biweekly at the most. This would dramatically reduce the potential risk to sources and methods. Fourth, and most importantly, there may be times when the Fleet Director of Intelligence (or higher authority) may deem the location of a particular ship, submarine or aircraft to be too sensitive. In such instances, they can simply remove the platform(s) from the briefing graphics. This would provide a final, fail-safe check against revealing any sensitive intelligence collection sources or methods. Together, these four factors would eliminate the possibility of compromising sources and methods, even with sophisticated algorithms of “pattern analysis.”

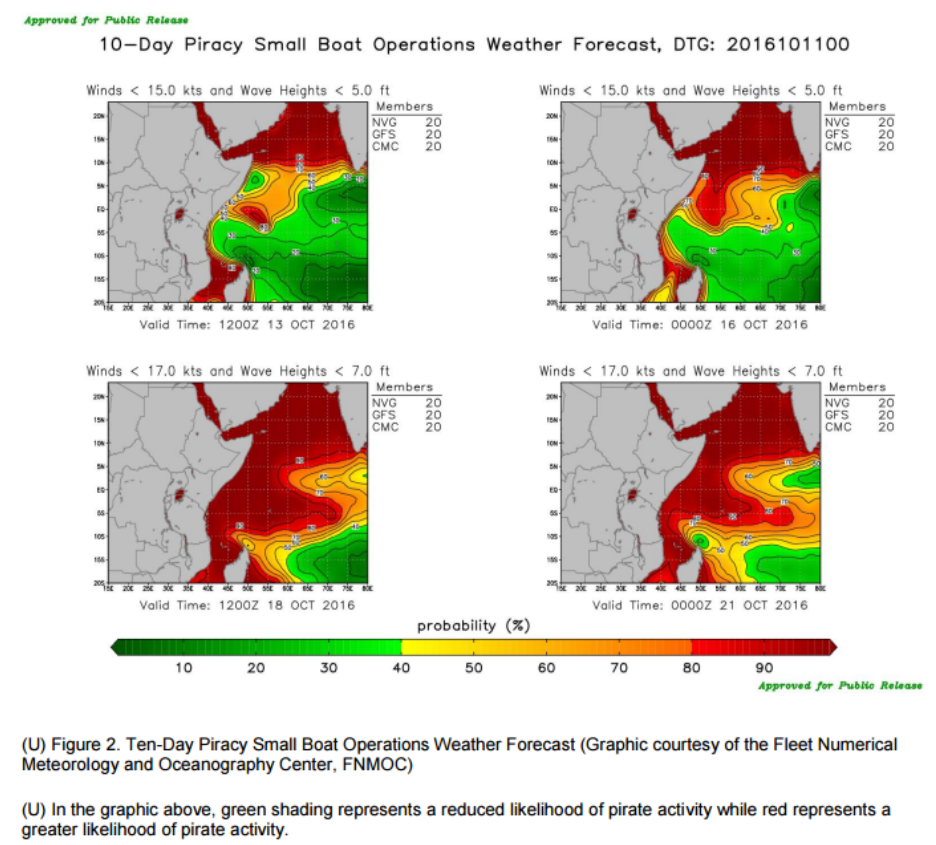

Such an initiative would not be entirely without precedent. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) already produces the “World Wide Threat to Shipping” and “Piracy Analysis Warning Weekly” reports, which provide graphic and textual laydowns of the global maritime domain as derived from unclassified sources. The recommendations outlined in this essay would represent an expansion of current efforts under the auspices of ONI, using the PFIF’s all-source data as the primary source.

The Rewards of Mass Enlightenment

Releasing such data would immediately benefit efforts to understand Chinese maritime strategy. It would open up whole new swaths of scholarship. Chinese actions could be directly correlated to Chinese words. Incidents could be placed in their correct context. Theories about China’s pursuit and use of sea power could be proposed and tested with new levels of rigor.

Better open source analysis would also benefit the intelligence community itself. The strengths of academic scholarship—such as understanding strategic and organizational culture—could be applied to the same questions that preoccupy USN analysts, perhaps yielding fresh insights. Efforts to contextualize the activities of China’s maritime militia, for example, would be especially welcome, given its peculiar social, cultural, and political roots.

While scholarship is valuable in and of itself, the ultimate purpose of such an initiative would be to improve the ability of our democracy to respond to the China challenge. Elected officials, who ultimately decide policy, take cues from public discourse. Thus, if wise policies are to be crafted, the broader American public must be fully aware of the threat that China’s pursuit of maritime power poses to American interests. This is especially important given that any proper response would require the whole nation to bear costs and accept risks. Unlike Russia, China’s actions are carefully calibrated not to arouse a somnolent American public. This places a very high premium on information about the actions that China is taking.

To be sure, information is not an antibiotic. Ingesting it in the right quantities at the right frequencies may not cure the disease. Indeed, there is already enough data in the public domain for Americans to see the key trends. Yet there remain some very smart people who cannot, or will not, recognize the perils we face. Even so, the correct antidote to intellectual biases is ever more information; as data accumulates, the naysayers must either alter their theories or risk self-marginalization.

Sharing facts about Chinese activities at sea is not just good for democracy, it is also smart diplomacy. At this point, merely shining the spotlight on Chinese maritime expansion is unlikely to persuade China to radically alter its strategy. The China of Xi Jinping is less moved by international criticism than the China of Hu Jintao or Jiang Zemin. However, releasing detailed data on Chinese activities at sea would likely have an impact on foreign publics, who will use it to draw more realistic conclusions about the implications of China’s rise. Moreover, making such information widely available would help counter spurious Chinese narratives of American actions as the root cause of instability in the Western Pacific. Both outcomes are in our national interest.

To adopt the approach advocated in this essay would require a political decision. On matters of national policy, naval intelligence professionals must yield to civilian leaders.7 In the end, then, this essay is for the politicians. And so is its last word: share with the scholars.

James E. Fanell is a retired U.S. Navy Captain whose last assignment was the Director of Intelligence and Information Operations for the U.S. Pacific Fleet and is currently a Fellow at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy.

Ryan D. Martinson is a researcher in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

1. 张元农, 周卓群, 李克一 [Zhang Yuannong, Zhou Zhuoqun, and Li Keyi] 潜航深海磨利刃 [“Sailing Submerged in the Deep Ocean to Sharpen Our Blade”] 人民海军 [People’s Navy], 8 October 2014, p. 3.

2. 顾曹华 [Gu Caohua] 动中抓建,铸造深蓝铁拳 [“Seize on Construction While in Action, Mold a Blue Water Iron Fist”] 人民海军 [People’s Navy] 8 January 2014, p. 3.

3. 李唐 [Li Tang] 海军常态化巡逻覆盖万里海疆 [“Normalized Naval Patrols Cover the Maritime Frontier”] 人民海军 [People’s Navy] 23 June 2014, p. 1

4. James E. Fanell, Remarks at USNI/AFCEA conference panel: “Chinese Navy: Operational Challenge or Potential Partner?”, San Diego, CA, 31 January 2013.

5. James E. Fanell, “The Birth of the Pacific Fleet Intelligence Federation”, Naval Intelligence Professionals Quarterly, October 2013.

6. Ibid. James E. Fanell, “The Birth of the Pacific Fleet Intelligence Federation”, Naval Intelligence Professionals Quarterly, October 2013.

7.The authority for conducting an effort such as this would require approval from the Director of National Intelligence and the various “Original Classification Authorities” as outlined in Executive Order 1352. “Executive Order 13526- Original Classification Authority”, The White House Office of the Press Secretary, 29 December 2009, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/executive-order-original-classification-authority

Featured Image: A sailor of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy aboard the aircraft carrier Liaoning. (REUTERS/XINHUA)