This article is part of a series that will explore the use and legal issues surrounding military zones employed during peace and war to control the entry, exit, and activities of forces operating in these zones. These works build on the previous Maritime Operational Zones Manual published by the predecessor of the Stockton Center for International Law, the International Law Department, of the U.S. Naval War College. A new Maritime Operational Zones Manual is forthcoming.

By LtCol Brent Stricker

Nuclear Weapons Free Zones (NWFZ) are an attempt to prohibit the use or deployment of nuclear weapons within a nation’s territory. None of the signatories to these treaties possess nuclear weapons, where NFWZs stand as a pledge not to develop these weapons. The established nuclear powers of the world have similarly pledged to respect some NFWZs.1 It remains to be seen whether such pledges will be observed or dismissed as a simple “scrap of paper.”2

Background

The legality of the use of nuclear weapons is an unsettled issue. The International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion stating the threat or use of nuclear weapons must be examined under the United Nations Charter Article 2(4) prohibition on the use of force and Article 51’s right of self-defense.3 The Court could not “conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defense in which the very survival of the state was at stake.”4

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was an early attempt to limit and eventually eliminate nuclear weapons. Article 1 of the NPT prohibits Nuclear Weapons States (NWS) from transferring nuclear weapons to a Non-Nuclear Weapon State (NNWS) or encouraging a NNWS to develop nuclear weapons. Article 6 of the NPT requires states to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

Since the signing of NPT, the number of NWS has expanded. Two of the newly acknowledged nuclear powers, India and Pakistan, never signed the treaty. North Korea signed and subsequently withdrew. Finally, Israel, a suspected and unacknowledged nuclear power, never signed the treaty.5

The concept of NWFZ predates the NPT with a proposal for a Central European NWFZ by the Soviet Union to the General Assembly in 1956.6 In 1958, Poland proposed the Rapaki Plan, “banning the manufacture, possession, stationing, and stockpiling of nuclear weapons and equipment, the proposal called for the prohibition of nuclear attacks against state members in the zone.” The proposal would have included Poland, Czechoslovakia, and East and West Germany. Such a proposal would have prevented NATO’s use of nuclear weapons and played to the Warsaw Pact’s advantage due to its overwhelming conventional forces arrayed against NATO, causing this proposal to fail.7

A NWFZ is either implemented unilaterally, through a state’s domestic law, or bilaterally through regional agreements to prohibit the possession, use, testing, and/or transit of nuclear weapons within a designated territory.8 A vital part of the viability of NWFZ is buy-in from the NWS. Typically, the NWS will sign negative security assurances to the NWFZ states pledging to respect the NWFZ’s prohibitions.9 The NWS may refuse to issue a negative security assurance due to other concerns. For example, none of the NWS have signed onto the South East Asian proposal due to its impact on freedom of navigation.10 It should be noted that four of the five NWFZs allow the vessels and aircraft of signatory states to transit their territory with nuclear weapons.11

A further potential limitation of NWFZs occurs when a NNWS is in a defensive treaty agreement with an NWS. To illustrate, Australia is a signatory to the South Pacific NWFZ but has stated it will rely on the United States’ nuclear deterrent capability for its defense. Australia also supports the United States by allowing assets to be based in Australia that forms part of the Communications, Command, Control and Intelligence (C3I) network the U.S. would use in a nuclear exchange.12

Current Nuclear Weapons Free Zones

There are currently nine NWFZs in existence. Five of these were created by regional agreements. Three of them were created by international treaty but only occur in unpopulated areas: Outer Space, the Moon, and the seabed. The last NWFZ was created unilaterally by Mongolia. NWFZs cover more than two billion people and 111 countries.13

African NWFZ (ANWFZ)

The Treaty of Pelindaba established the African NWFZ. It was opened for signature on April 11, 1996, and came into effect on July 15, 1990.[14] Article 3 of the treaty renounces nuclear weapons, and the signatories pledge “not to conduct research on, develop, manufacture, stockpile or otherwise acquire, possess or have control over any nuclear explosive device by any means anywhere” and “not to seek or receive any assistance in the research on, development, manufacture, stockpiling or acquisition, or possession of any nuclear explosive device.” Article 4 is a prohibition on stationing nuclear weapons on their territory, but it allows individual nations the ability to allow foreign aircraft and ships to visit or exercise innocent passage without reference to whether such aircraft and ships may be armed with nuclear weapons. This thereby creates a loophole allowing nuclear weapons within the NWFZ. The treaty also makes no mention of control or assistance to an NWS in a defensive agreement.

There are three protocols to the treaty for other nations to sign. Protocol I calls for the 5 acknowledged NWS to pledge not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against signatories or on territory within the African NWFZ. Protocol II is a nuclear weapons test ban. Protocol III is open for Spain and France to sign onto, pledging to the Treaty on behalf of their dependent territories within the African NWFZ. The five acknowledged NWS have signed Protocols I and II.

The United States made a cautionary reservation when signing onto the Protocols by “reserve[ing] the right to respond with all options implying possible use of nuclear weapons, to a chemical or biological weapons attack by a member of the zone.”15 These Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) Reservations mean the United States may still use nuclear weapons in the African NWFZ.

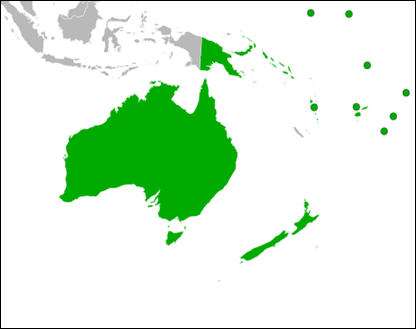

South Pacific NWFZ (SPNFZ)

The Treaty of Rarotonga established the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone. It was signed on August 6, 1985, and came into effect on December 11, 1985. All five acknowledged NWS have signed onto its Protocols. Annex 1 to the treaty describes the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone, which includes both territorial land, waters, and the high seas. Article 3 of the treaty pledges signatories “not to manufacture or otherwise acquire, possess or have control over any nuclear explosive device by any means anywhere inside or outside the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone” and “not to seek or receive any assistance in the manufacture or acquisition of any nuclear explosive device.” Article 5 prohibits stationing nuclear weapons on the territory of signatory states. Article 5 also includes a loophole allowing signatory states to allow visits and transit by foreign aircraft and ships that may be armed with nuclear weapons. Article 7 includes a prohibition on dumping radioactive matter within the SPNFZ.”16

A second loophole appears in Article 3(c) of the treaty. There is no prohibition on the research of nuclear weapons. This leaves signatories the option to research nuclear weapons. The most likely being Australia if it needs to rapidly develop such weapons for nuclear deterrence.17

Australia poses a unique challenge to the SPNFZ due to its defensive alliance with the United States. The Australia, New Zealand, and the United States Security Treaty (ANZUS) was signed in 1951, joining the three nations in a collective security arrangement.18 New Zealand banned nuclear-powered vessels in 1984 and later created its own nuclear-free zone with the passage of the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987. In response, the Reagan Administration suspended New Zealand’s obligations under the ANZUS Treaty.19 Australia remains a party.

Australia has publicly stated in its 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper it would rely on the deterrence power of the United States’ nuclear weapons.20 Australia also hosts US military installations that are vital to worldwide command and control.21 Undoubtedly, these facilities would be part of the Communication, Command, Control, and Intelligence (C3I) the United States would rely on during a nuclear crisis. Australia is in a dilemma then of being a party to the SPNFZ and an ally of an NWS poised to potentially assist in a nuclear attack. The treaty does not address this issue of C3I by a signatory state, with Article 3(c) only prohibiting the manufacture or acquisition of nuclear weapons.22 Australia’s decision to cancel an order of French diesel-electric submarines and order nuclear-powered submarines from the United States does not violate SPNFZ. These submarines will only be nuclear-powered, and will not house nuclear weapons.

Southeast Asian NWFZ (SEANWFZ)

The Bangkok Treaty established the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone. The treaty was signed on December 15, 1995, and went into effect on March 28, 1997. The ten members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) agreed not to “develop, manufacture or otherwise acquire, possess or have control over nuclear weapons; station or transport nuclear weapons by any means; test or use nuclear weapons.”23 The Treaty also prohibited control, stationing, or testing of nuclear weapons in the SEANWFZ.24 The Bangkok Treaty thus closed the visit, transit, research, and control loopholes for vessels and aircraft with nuclear weapons. Finally, the Bangkok Treaty prohibited dumping or discharging into the atmosphere of radioactive material or waste.25

The SEANWFZ is striking due to the size of the zone defined in the treaty. The zone is expanded to include the continental shelf and exclusive economic zones of the signatory nations.26 The Zone embraces an area of strategic importance to maritime shipping. The treaty would prevent the 5 NWS from transporting nuclear weapons through this zone. This is likely why no NWS has signed onto the treaty’s protocols and provides a negative security assurance to the ASEAN signatories.27

Central Asian NWFZ (CANWFZ)

The Central Asian Nuclear Weapons Free Zone was created by the Treaty of Semipalatinsk. The treaty was signed on September 8, 2006, and went into effect on Mar 21, 2009. The CANWFZ is defined as the land, internal waters, and airspace of the signatories.28 Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, all former Soviet Republics, agreed to prohibit research, development, manufacture, stockpiling, acquisition, possession, or control over any nuclear weapon. The treaty also prohibited the location of such weapons in the zone. The treaty closed the control loophole for aircraft and vessels harboring nuclear weapons while transiting through the zone. Article 4 of the treaty allows the individual states to determine how to handle passage and transit by foreign ships, aircraft, and ground transportation, thus leaving loopholes open. The five acknowledged NWS have signed onto the Protocols of the treaty.

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan have a similar problem to Australia noted above. They are members of the 1992 Tashkent Collective Security Treaty, which includes the Russian Federation, one of the five acknowledged NWS. Article 4 of the treaty requires the Member States to provide all assistance, including military assistance, if one member is attacked.29 It remains to be seen how this will affect the CANWFZ.

Mongolian NWFZ

The Mongolian Nuclear Weapons Free Zone is unique as a unilateral action by domestic law similar to the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone noted above. Mongolia made this declaration in 1992 and called for a regional NWFZ.30 This seemed improbable as Mongolia is surrounded by the Russian and Chinese NWS. The Mongolian NWFZ was recognized with UN General Assembly Resolution 53/77 D.31

Mongolia’s history makes its NWFZ unique, considering it was caught between the two struggling NWS for most of its existence. Emerging as an independent nation within the Soviet sphere of influence after centuries of involvement with Imperial China, Mongolia continued as part of the struggle between the Sino-Soviet split.32 Russia and China signed negative security assurances with Mongolia in 1993 and 1994, respectively. The other acknowledged NWS has agreed to respect Mongolia’s NWFZ.33

Latin American and the Caribbean NWFZ

The Treaty of Tlatelolco created the Latin American NWFZ. It was signed on February 1967 and went into effect on April 25, 1969. Article 1 of the treaty prohibits “the testing, use, manufacture, production or acquisition, by any means, of any nuclear weapon [signatory states] by order of third parties or in any other way,” and “the receipt, storage, installation, location or any form of possession of any nuclear weapon, directly or indirectly, by [signatory states], by mandate to third parties or in any other way.” The NWFZ is defined in Article 4 of the treaty in a manner similar to the 1939 Panama Declaration expanding the zone into international waters.34 Article 18 makes one exception for the peaceful use of nuclear explosions. All five acknowledged NWS have signed Additional Protocol II of the treaty respecting the NWFZ with the United States stating a reservation on the right to transit of nuclear weapons through the zone.35

The Latin American and Caribbean NWFZ has a similar problem shared by Australia and the CANWFZ due to the mutual defense obligations imposed by the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance. This treaty was signed in 1947 by all of the states in North and South America, including the nuclear-armed United States. While it may be in decline with the withdrawal of member states and attempts to replace this treaty with sub-regional treaties, it remains valid international law.

Antarctica, the Moon, and Seabed NWFZ

It is interesting to note that the first NWFZs were created in places that humans normally do not inhabit: Antarctica, Outer Space, and the deep seabed. Article V of the Antarctic Treaty prohibits nuclear explosions or the dumping of radioactive material on the continent. Article IV of the Outer Space Treaty prohibits the stationing of nuclear weapons or weapons of mass destruction in space or on celestial bodies. This prohibition also prohibits the militarization of celestial bodies. The Outer Space Treaty does not address military activities in orbit, though. Article I of the Seabed Arms Control Treaty prohibits the emplacement of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction including structures to test, launch, or store such devices on the deep seabed.

It has been speculated that support for these NWFZs by the five acknowledged NWS was to limit the area to deploy nuclear weapons and the increased pressure on the arms race this would impose.36 The strategic value of making Antarctica off-limits for nuclear weapons seems to belie this argument since all NWS, acknowledged or not, are located in the Northern Hemisphere. The future possibilities for weaponizing outer space may render the Space NWFZ irrelevant.

2017 United Nations Nuclear Prohibition Treaty

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons could create the largest NWFZ in the world. It was proposed on 23 December 2016 with UN General Assembly Resolution 71/258. It was open for signature on September 20, 2017, and in effect on January 22, 2021.37 The NWS acknowledged and unacknowledged, do not support the treaty.38

Under Article 1 of the treaty: “Each State Party undertakes never under any circumstances to:

(a) Develop, test, produce, manufacture, otherwise acquire, possess or stockpile nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices;

(b) Transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or control over such weapons or explosive devices directly or indirectly;

(c) Receive the transfer of or control over nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices directly or indirectly;

(d) Use or threaten to use nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices;

(e) Assist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Treaty;

(f) Seek or receive any assistance, in any way, from anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Treaty;

(g) Allow any stationing, installation, or deployment of any nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices in its territory or at any place under its jurisdiction or control.”

A stated reason for the treaty is the failure of the promises under NPT for the acknowledged NWS to eliminate nuclear weapons. Regional NWFZs, as discussed in this chapter, have increased the area on Earth for nuclear weapons, but as noted above, these are all reliant on Negative Security Assurances by NWS.39 As noted above, many NWS refuse to provide such assurances when transit rights are impacted. It is also unclear how useful a NWFZ agreement will be when one of its signatories is involved in a collective defense agreement with a NWS if an armed conflict occurs. It seems unlikely that the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons will be supported by the NWS anytime soon.40

LtCol Brent Stricker, U.S. Marine Corps serves as the Director for Expeditionary Operations and as a military professor of international law at the Stockton Center for International Law at the U.S. Naval War College. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Navy, the Naval War College, or the Department of Defense.

References

[1] See the Southeast Asian NWFZ where no NWS has granted a negative security assurance due to its prohibition on transit of nuclear weapons through the zone.

[2] “Scrap of paper” was allegedly the phrase used by German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, on 4 August 1914 to justify ignoring the 1839 Treaty of London guaranteeing the neutrality of Belgium. Germany was caught in a two-front war for national survival, and its war plans called for sending military forces in and across Belgium. T. G. Otte (2007) A “German Paperchase”: The “Scrap of Paper” Controversy and the Problem of Myth and Memory in International History, Diplomacy and Statecraft, 18:1, 53-87, 55.

[3] Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (Advisory Opinion of July 8, 1996) ICJ, 35 ILM 809 & 1343 (1996), Para. 105(2)(C).

[4] Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (Advisory Opinion of July 8, 1996) ICJ, 35 ILM 809 & 1343 (1996), Para. 105(2)(E).

[5] Paul J. Magnarella, “Attempts to Reduce and Eliminate Nuclear Weapons through the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and the Creation of Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones” PEACE & CHANGE, Vol. 33, No. 4, October 2008 507-521, 510.

[6] Gawdat Bahgat, A Nuclear Weapons Free Zone in the Middle East – A Pipe Dream?, The Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Volume 36, Number 3, Fall 2011 360-383, 364.

[7] Bahgat at 364.

[8] Magnarella at 511; Bahgat at 362.

[9] Bahgat at 363.

[10] Bahgat at 363.

[11] Elizabeth Mendenhall, “Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones and Contemporary Arms Control” STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY WINTER 2020 122-151, 131.

[12] Michael Hamel-Green (2018) The implications of the 2017 UN Nuclear Prohibition Treaty for existing and proposed nuclear-weapon-free zones, Global Change, Peace & Security, 30:2, 209-232, 221.

[13] Bahgat at 365.

[14] Bahgat at 365-66.

[15] Bahgat at 363.

[16] Hamel- Green at 218.

[17] Hamel-Green at 222.

[18] ANZUS Treaty, Article V; Richard Baker, “ANZUS On Two Legs?” Far Eastern economic review, 1989-05-25, Vol.144 (21), p.30.

[19] Richard Baker, “ANZUS On Two Legs?” Far Eastern economic review, 1989-05-25, Vol.144 (21), p.30.

[20] Hamel-Green at 218.

[21] Hamel-Green at 219.

[22] Hamel-Green at 221.

[23] Bangkok Treaty Article 3.

[24] Bangkok Treaty Article 3.

[25] Bangkok Treaty, Article 3.

[26] Bangkok Treaty Article 2.

[27] Marangella at 515; Hamel-Green at 212.

[28] Treaty of Semipalatinsk Article 2.

[29] Collective Security Treaty Organization http://www.odkb.gov.ru/start/index_aengl.htm

[30] Marangella at 512.

[31] UN General Assembly Resolution 53/77 D (1998)

[32] Enkhsaikhan Jargalsaikhan (2005) MONGOLIA, The Nonproliferation Review, 12:1, 153-162, 156.

[33] Jargalsaikhan at 156.

[34] Article 4, Treaty of Tlateloco.

[35] Hamel-Green at 217.

[36] Mendenhal at 124-25.; See Doore at 7-8 for a discussion of the proposed demilitarization of the deep seabed and draft treaties submitted to the Eighteen Nation Disarmament Conference in 1969 by the Soviet Union and the United States with the Soviets advocating for denuclearization and the U.S. advocating for banning weapons of mass destruction. Article 1 of the Seabed Treaty is a combination of both positions.

[37] As of this writing, 56 member nations have signed the treaty. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/tpnw

[38] Hamel-Green at 209-10.

[39] Hamel-Green at 210-12.

[40] “‘We do not intend to sign, ratify or ever become party to it. Therefore, there will be no change in the legal obligations on our countries with respect to nuclear weapons.” United States Mission to the United Nations, Joint Press Statement from the Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the United States, United Kingdom, and France Following the Adoption of a Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapons, New York City, July 7, 2017 Hamel-Green at 214 (https://usun.usmission.gov/joint-press-statement-from-the-permanent-representatives-to-the-united-nations-of-the-united-states-united-kingdom-and-france-following-the-adoption/).

Featured Image: The “Baker” explosion, part of Operation Crossroads, a nuclear weapon test by the United States military at Bikini Atoll, Micronesia, on 25 July 1946. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)