By Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

Introduction

Russia and North Korea are both fielding a novel type of naval weapon – nuclear-armed torpedo drones. These new weapons introduce a variety of strategic and operational challenges that further complicate a worsening threat environment. They also pose critical legal questions about whether their intended concepts of operation are lawful. These weapons have a fearsome potential to weaponize the maritime environment, and precise questions of their legality should be resolved in order to dissuade their proliferation.

North Korea and Russia’s Doomsday Torpedoes

On July 28, North Korea displayed a new nuclear-armed drone torpedo at the 2023 Victory Day Parade in Pyongyang. Although its official classification is unknown, the new weapon is likely a Haeil-class drone torpedo. The nuclear torpedo drone is approximately 52 feet long and 5 feet in diameter, has an estimated range of about 540 nautical miles, and can be fitted with a conventional or nuclear warhead. It could therefore be used against targets in both South Korea and Japan. The torpedo drone appears to have three air filters over the propulsion space for snorkeling, is likely powered by a diesel-electric (battery) propulsion system, has an average speed of 4.6 knots, and can operate at depths between 260-300 feet. Given the size of the drone, North Korea does not have a submarine large enough to launch it, which suggests that the new weapon system will need to be launched from shore, a floating platform, or a modified surface vessel.

The nuclear-armed underwater drone can be used to attack coastal naval installations or cities with little or no warning, providing North Korea with a strategic nuclear weapons delivery option that is difficult to detect and defend against. Thus, the Haeil-class drone provides North Korea with an additional strike option, increasing the resilience of its nuclear forces and making them less vulnerable to preemption or counterattack.

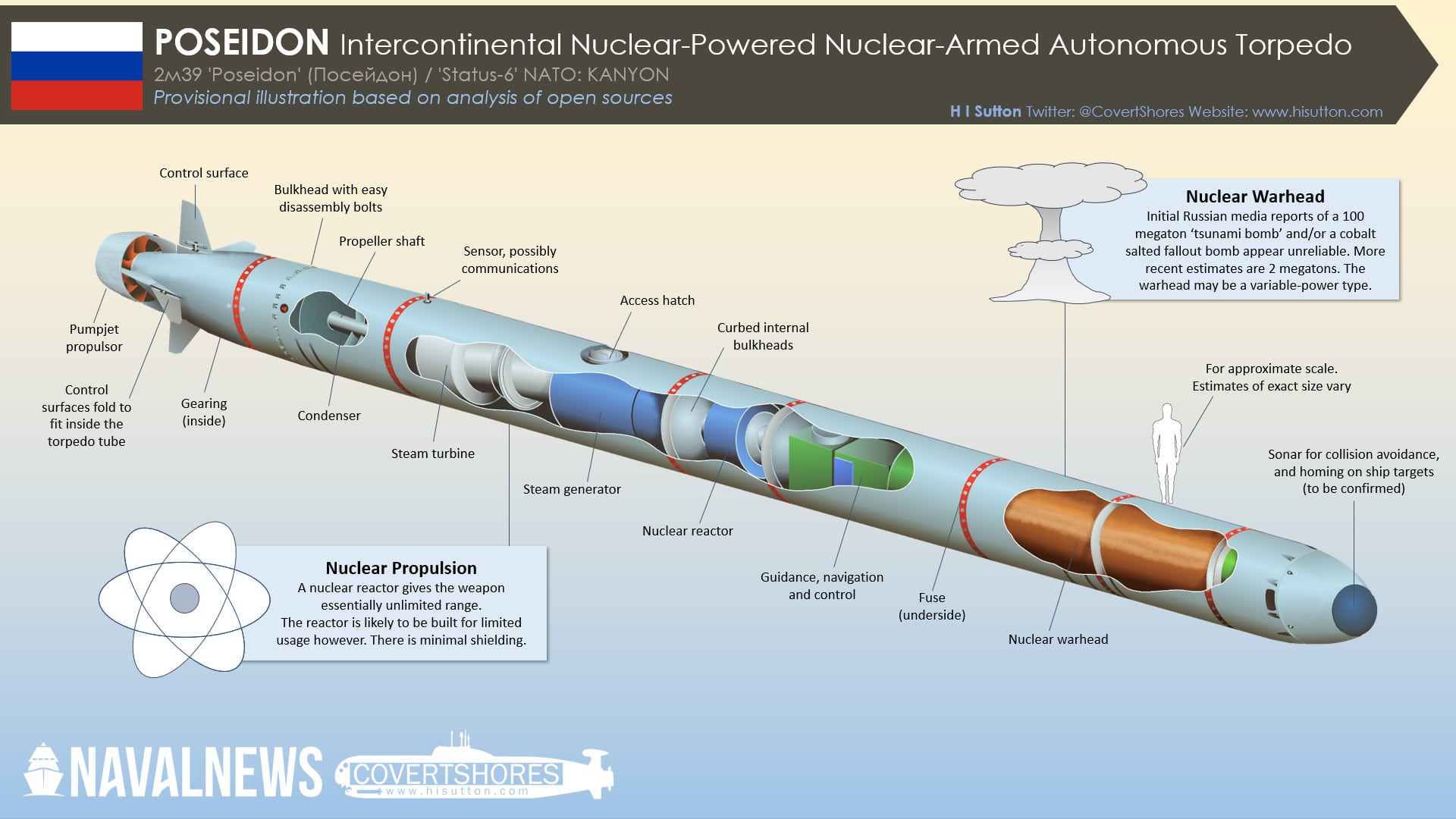

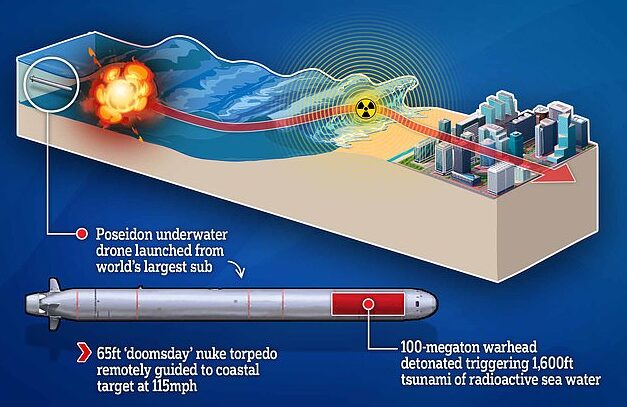

The Haeil-class drone torpedo is similar to (but smaller than) the Russian Poseidon, an intercontinental, nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed autonomous torpedo that was first revealed by the Russian Navy in 2015. The Poseidon (also known as Kanyon or Status 6) can reportedly operate at speeds of around 70-100 knots and at depths of around 3,300 feet, which means it can outrun and out dive any conventional torpedo. The weapon is also equipped with “acoustic tracking devices and other traps” that make it difficult to detect. Moreover, the drone is equipped with its own power source—a nuclear reactor—which gives the torpedo unlimited range. Once launched, the drone is designed to be controlled by both remote communications and onboard automation. In January 2023, TASS reported that Russia had produced the first batch of Poseidon torpedoes for “use by the [K-329] Belgorod special-purpose nuclear submarine.” The Belgorod submarine can carry up to six Poseidon torpedoes, and will deploy to the Pacific Fleet area of responsibility as early as late 2024 or early 2025.

These drone torpedoes can be armed with up to a 100-megaton nuclear warhead, but their primary method of destruction is less about directly impacting targets. Instead, they focus on weaponizing the immediate aftereffects of nuclear detonations in the maritime environment. These nuclear torpedo drones are designed to trigger a radioactive tsunami-like ocean swell that destroys coastal cities and renders them uninhabitable, potentially resulting in large-scale displacement and millions of deaths. The legality of this concept of operations deserves closer scrutiny.

Legal Means and Methods of Warfare

Generally, the legal right of the belligerents to adopt means or methods of warfare during an international armed conflict is not unlimited (AP I, art. 35; HR, art. 22; Newport Manual, § 6.1). Specifically, a belligerent does not have the unlimited right to inflict superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering on the opposing belligerent (HR, art. 23; Newport Manual, § 6.1). Weapons law “regulates which weapons and means can lawfully be used during an armed conflict,” and is comprised on both customary international law and treaties (St. Petersburg Declaration; Newport Manual, § 6.2). The customary international law principle of distinction and the prohibition of unnecessary suffering regulate the legality of the means of warfare (Newport Manual, § 6.2). Weapons law is also codified in treaties, such as the Environmental Modification (ENMOD) Convention and Additional Protocol I (AP I) to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

Damage to the environment is a concern. AP I places restrictions on weapons that “are intended or may be expected to cause widespread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment (AP I, art. 35(3); Newport Manual, § 6.3).” AP I further provides that the belligerent shall take care “in warfare to protect the natural environment against widespread, long-term and severe damage,” which includes a prohibition of the “use of methods or means of warfare which are intended or may be expected to cause such damage to the natural environment…” that prejudices the health or survival of the civilian population (AP I, art. 55(1); Newport Manual, § 6.3). The International Committee of the Red Cross interprets “long-term” to include damage over a period of decades (ICRC Commentary to AP I, ¶ 1453(c)).

The ENMOD convention prohibits States’ parties from engaging “in military or any other hostile use of environmental modification techniques having widespread, long-lasting or severe effects as the means of destruction, damage or injury to any other State Party (ENMOD Convention, art. I; Newport Manual, § 6.3.1).” For the purposes of the Convention, the terms “widespread,” “long lasting,” and “severe” have been interpreted by the convention’s Consultative Committee of Experts. “Widespread” means “encompassing an area on the scale of several hundred square kilometres.” “Long-lasting” means “lasting for a period of months, or approximately a season.” Finally, “severe” means “involving serious or significant disruption or harm to human life, natural and economic resources or other assets.” (See ENMOD, Understanding Relating to Article I). “Environmental modification techniques” are defined in article II as “any technique for changing—through the deliberate manipulation of natural processes—the dynamics, composition or structure of the earth, including its biota, lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere.” Thus, the convention prohibits the use of “modification techniques that result in the environment itself being characterized as a weapon, rather than prohibiting certain military activities that cause damage to the environment (Newport Manual, § 6.3.1).”

The prohibitions in AP I and the ENMOD Convention are, therefore, not duplicative (ICRC Commentary to AP I, ¶ 1450). AP I protects the natural environment against damage which could be inflicted on it by any weapon, whereas the ENMOD Convention prevents the use of environmental modification techniques as a weapon. Additionally, AP I only applies during an international armed conflict, whereas the ENMOD Convention has a wider application—it applies to the use of environmental modification techniques for hostile purposes, even in cases where there is no international armed conflict.

On the one hand, the ENMOD Convention prohibits the deliberate manipulation of natural processes to change “the dynamics, composition or structure of the Earth, including its biota, lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere, or of outer space, with the intention of damaging the armed forces of another State…, its civilian population, towns, industries, agriculture, transportation and communication networks, or its natural resources and wealth (ICRC Commentary to AP I, ¶ 1451).” Therefore, the convention does not prohibit environmental modifications that cause widespread, long-lasting, or severe damage as such, but only if they are used to cause damage to another State (ICRC Commentary to AP I, ¶ 1452).

AP I, on the other hand, “prohibits damaging the natural environment by any means whatsoever, whether direct or indirect, as opposed to effects on the human environment,” that is, “to external conditions and influences which affect the life, development and the survival of the civilian population and living organisms.” (ICRC Commentary to AP I, ¶ 1451). AP I therefore prohibits the use of any means that cause widespread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment (ICRC Commentary to AP I, ¶ 1452).

Taken together, AP I and the convention prohibit: (a) “any direct action on natural phenomena of which the effects would last more than three months or a season…;” (b) any direct action on natural phenomena of which the effects would be widespread or severe… regardless of the duration…” or (c) “any method of conventional or unconventional warfare which, by collateral effects, would cause widespread and severe damage to the natural environment as such, whenever this may occur over a period of decades (ICRC Commentary to AP I, ¶ 1453).”

Conclusion

Armed with multi-megaton nuclear warheads, these torpedo drones will be detonated along an adversary’s coast to create a powerful radioactive tsunami to destroy coastal cities and naval bases. Given that the concept of operations for these new weapons might unlawfully modify and weaponize the natural environment, both the North Korean Haeil and Russian Poseidon torpedo drones are likely unlawful weapons per se under the law of armed conflict.

The unleashing of environmental forces in such a manner is contrary to the law of war and likely violates the ENMOD Convention, which prohibits any method of warfare for changing—through the deliberate manipulation of natural processes—the dynamics, composition, or structure of the Earth (DoD Law of War Manual, §§ 6.10.1-6.10.2; FM 6-27, ¶¶ 2-139, 2-140). Examples of environmental effects likely to be widespread (encompassing an area of several hundred square kilometers), long-lasting (for a period of months or a season), or severe (serious or significant disruption or harm to human life, natural and economic resources, or other assets) likely include the inducement of a radioactive tsunami. Unlike a conventional or nuclear weapon designed to destroy enemy forces, the Haeil and Poseidon torpedoes weaponize the natural environment to inflict destruction and ignore the distinction between the enemy’s armed forces and the civilian population. (Newport Manual, § 6.3.1). As parties to AP I and the ENMOD Convention, both North Korea and Russia have legal obligations not to use environmental techniques that are prohibited by the Convention, or to employ means or methods of warfare that can cause widespread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment.

Professor Raul (Pete) Pedrozo, Captain, USN, Ret., is the Howard S. Levie Professor on the Law of Armed Conflict, U.S. Naval War College, Stockton Center for International Law. Prior to his retirement from active duty after 34 years of service, he served in numerous positions advising senior military and civilian Defense officials, including as the senior legal advisor to Commander, U.S. Pacific Command. He also served as the Director of the Navy’s International and Operational Law Department in the Pentagon.

The views expresses are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Naval War College.

Featured Image: Pyongyang, July 27, 2023 – Supreme Leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Kim Jong Un applauds as Haeil-class nuclear torpedo drones are featured in a military parade. (Photo via North Korean state media)