This article originally featured on CIMSEC on August 25, 2015, and has been updated for inclusion into the Russia Resurgent Topic Week.

By Sally DeBoer

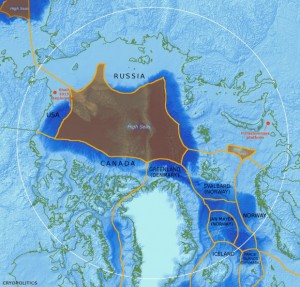

On August 4th, the Russian Federation’s Foreign Ministry reported that it had resubmitted its claim to a vast swath (more than 1.2 million square kilometers, including the North Pole) of the rapidly changing and potentially lucrative Arctic to the United Nations. In 2002, Russia put forth a similar claim, but it was rejected based on lack of sufficient support. This latest petition, however, is supported by “ample scientific data collected in years of arctic research,” according to Moscow. Russia’s latest submission for the United Nation’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf’s (CLCS) consideration coincides with increased Russian activity in the High North, both of a military and economic nature. Recent years have seen Russia re-open a Soviet-era military base in the remote Novosibirsk Islands (2013), with intentions to restore a collocated airfield as well as emergency services and scientific facilities. According to a 2015 statement by Russian Deputy PM Dmitry Rogozin, the curiously named Academic Lomonsov, a floating nuclear power plant

built to provide sustained operating power to Arctic drilling platforms and refineries, will be operational by 2016. Though surely the most prolific in terms of drilling and military activity, Russia is far from the only Arctic actor staking their claim beyond traditional EEZs in the High North. Given the increased activity, overlapping claims, and dynamic nature of Arctic environment as a whole, Russia’s latest claim has tremendous implications, whether or not the United Nations CLCS provides a recommendation in favor of Moscow’s assertions.

The Claim:

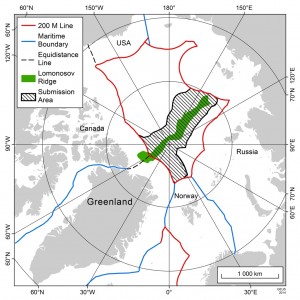

Russia’s August 2015 claim encompasses an area of more than 463,000 square miles of Arctic sea shelf extending more than 350 nautical miles from the shore. If recognized, the claim would afford Russia control over and exclusive rights to the economic resources of part of the Arctic Ocean’s so-called “Donut Hole.” As the New

York Times’ Andrew Kramer explains, “the Donut Hole is a Texas sized area of international waters encircled by the existing economic-zone boundaries of shoreline countries.” As such, the donut hole is presently considered part of the global commons. Moscow’s claim is also inclusive of the North Pole and the potentially lucrative Northern Sea Route (or Northeast Passage), which provides an increasingly viable shipping artery between Europe and East Asia. With an estimated thirteen percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and thirty percent of its undiscovered natural gas, the Arctic’s value to Russia goes well beyond strategic advantage and shipping lanes. Recognition by the CLCS of Russia’s claim (or any claim, for that matter) would shift the tone of activity in the Arctic from generally cooperative to increasingly competitive, as well as impinge on the larger idea of a free and indisputable global common.

The Law:

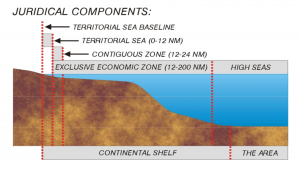

As most readers likely already know, the United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) allows claimants 12nm of territorial seas measured from baselines that normally coincide with low-water coastlines and an exclusive economic zone (EEZ)

extending to 200 nautical miles (inclusive of the territorial sea). Exploitation of the seabed and resources beyond 200nm requires the party to appeal to the International Seabed Authority unless that state can prove that such resources lie within its continental shelf. Marc Sontag and Felix Luth of The Global Journal explain that “under the law, the continental shelf is a maritime area consisting of the seabed and its subsoil attributable to an individual coastal state as a natural prolongation of its land and territory which can, exceptionally, extend a states right to exploitation beyond the 200 nautical miles of its EEZ.” Such exception requires an appeal to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), a panel of experts and scientists that consider claims and supporting data. Essentially, the burden is on Russia to provide sufficient scientific evidence that its continental shelf (and thus its EEZ) extends underneath the Arctic. In any case, as per UNCLOS Article 76(5), such a continental shelf cannot exceed 350 nm from the established baseline. Russia’s latest claim is well beyond this limit; the Federation has stated that the 350 nm limit does not apply to this case because the seabed and its resources are a “natural components of the continent,” no matter their distance from the shore.

The CLCS will present its findings in the form of recommendations, which are not legally binding to the country seeking the appeal. Though Russia has stated it expects a result by the fall, the commission is not scheduled to convene until Feburary or March of 2016 and, as such, there will be a significant waiting period before any recommendation will be made.

Rival Claimants:

Russia is far from the only Arctic actor making claims beyond the 200 nautical mile EEZ. Denmark, for instance, jointly submitted a claim with the government of Greenland expressing ownership over nearly 900,000 square kilometers of the Arctic (including the North Pole) based on the connection between Greenland’s continental shelf and the Lomonosov Ridge, which spans  nearly the entire diameter of the donut hole. This claim clearly overlaps Russia’s latest submission, which is also based on the claim that the ridge represents an extension of Russia’s continental shelf. Though there is no dispute on the ownership of the ridge, both Russia and Denmark claim the North Pole. Both nations have recently expressed a desire to work cooperatively on a resolution, though a Russian Foreign ministry statement did estimate a solution could take up to 10-15 years. Also of note: this has note always been Russia’s tune on the matter (See here and here).

nearly the entire diameter of the donut hole. This claim clearly overlaps Russia’s latest submission, which is also based on the claim that the ridge represents an extension of Russia’s continental shelf. Though there is no dispute on the ownership of the ridge, both Russia and Denmark claim the North Pole. Both nations have recently expressed a desire to work cooperatively on a resolution, though a Russian Foreign ministry statement did estimate a solution could take up to 10-15 years. Also of note: this has note always been Russia’s tune on the matter (See here and here).

Similarly, Canada is expected to make a bid to extend its Arctic territory. Notably, Canada claims sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, a shipping route connecting the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay based on historical precedent and its orientation to baselines drawn around the Arctic Archipelago. The U.S. maintains that the Northwest Passage should be an international strait. Though they have yet to submit a formal claim to the UN’s CLCS, one has reportedly been in preparation since 2013. According to reports, Canada delayed a last-minute claim at the behest of PM Stephen Harper, who insisted the claim include the North Pole. If this holds true, Canada’s claim will likely overlap both Russia and Denmark’s submissions to the CLCS. If the CLCS were to recognize the legitimacy of two or more states’ overlapping claims, the actors have the option to bilaterally or multilaterally resolve the issue to their satisfaction; developing such a resolution is beyond the scope of the commission.

Implications:

Likely, Russia’s submission to the United Nations is part of a larger campaign by Moscow to reassert and re-establish its influence in the international order by virtue of its status Arctic influence. Regardless of approval or rejection by the UN, Russia’s expansive claim highlights Moscow’s very serious intention to control and exploit the Arctic. As the Christian Science Monitor’s Denise Ajiri explains, “a win would mean access to sought after resources, but the petition itself underscores Russia’s broader interest in solidifying its footing on the world stage.” With much of Western Europe reliant on Russian oil and natural gas, the Arctic and its resources represent an opportunity for the Kremlin to boost their position in the international order and develop a source of sustained and significant income. Russia may be acting within the letter of the law on the issue of their claim at this time, but it’s hard to separate that compliance from the Federation’s significant investment in the militarization of the Arctic, frequent patrols along the coastline of Arctic neighbors, and expenditure on the economic exploitation of the High North. For now, the donut hole remains part of the global commons and therefore free from direct exploitation or claim of sovereignty. The burden of proof on any one state to claim an extension of their continental shelf is truly enormous, but as experts and lawyers at the CLCS pore over these claims, receding Arctic ice combined with economic and strategic interests of the claimants will likely increase the claimants’ sense of urgency.

Sally DeBoer is a 2009 graduate of the United States Naval Academy and a recent graduate of Norwich University’s Master of Arts in Diplomacy program. She can be reached at Sally.L.DeBoer@gmail(dot)com or on twitter @SallyDeBoer.