This piece was originally published by the Lawfare Institute in Cooperation with Brookings and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By James Kraska

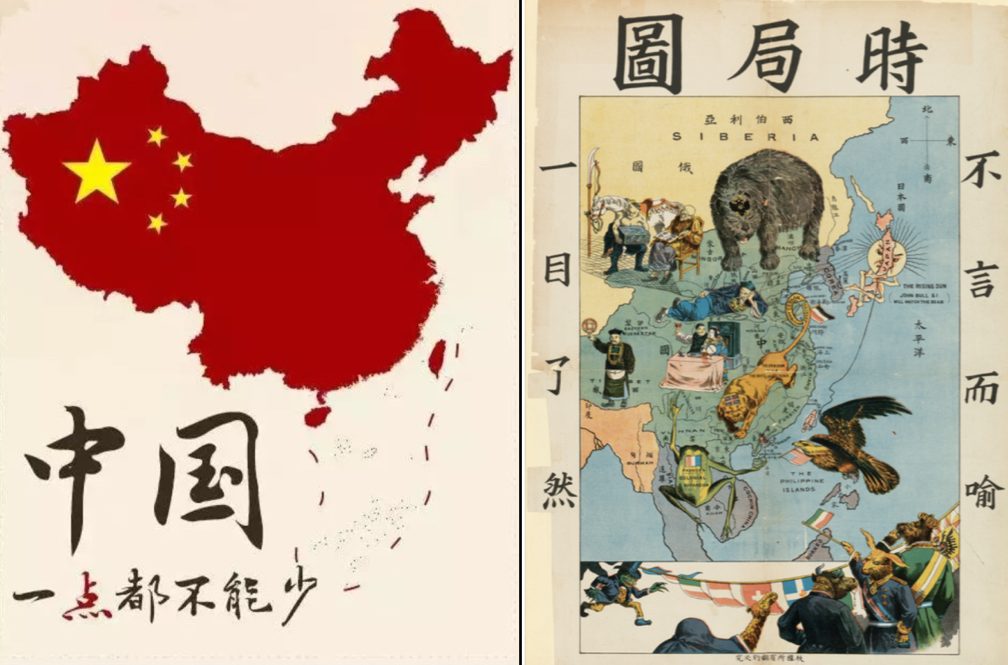

The recent Philippine-China Arbitration Award determined that China’s construction of artificial islands, installations and structures on Mischief Reef, Subi Reef, and Hughes Reef were unlawful interference with the Philippines’ exclusive sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the seabed of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf. Since the three features are low-tide elevations (LTEs), rather than islands, they are incapable of appropriation and are merely features of the Philippine continental shelf, albeit occasionally above water at high tide in their natural state. Although the tribunal’s legal judgment with regard to China’s activities was correct, its reasoning was a bit too categorical. This article adds further fidelity to the tribunal’s determination by distinguishing between lawful foreign military activities on a coastal state’s continental shelf, and unlawful foreign activities on the continental shelf that affect the coastal states sovereign rights and jurisdiction over its resources – a distinction that evaded the tribunal’s analysis.

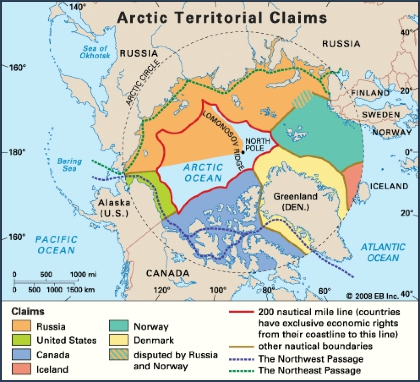

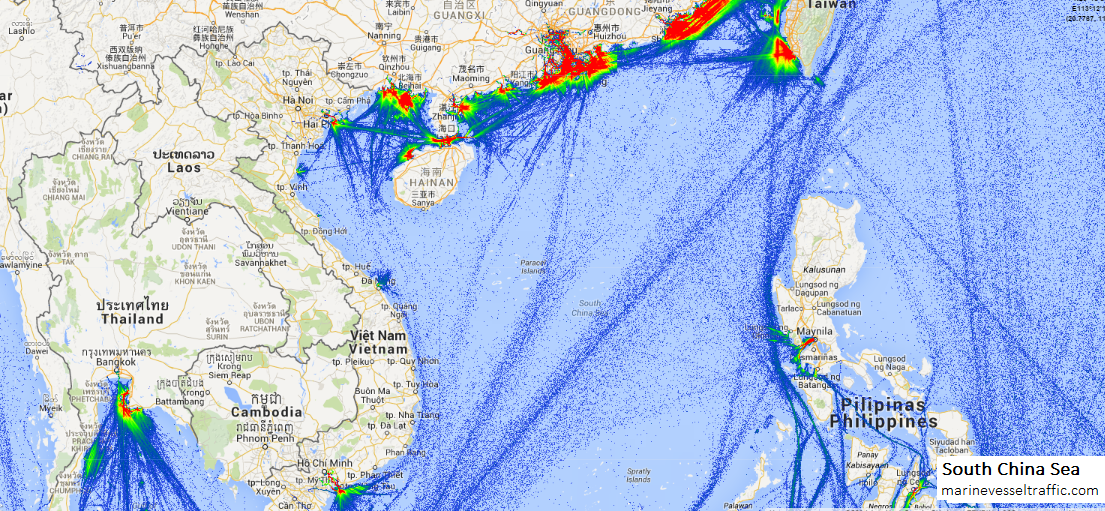

It is important to understand the lawful scope of foreign military activity on the seabed of a coastal state’s EEZ or continental shelf, as the issue is likely to recur. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, for example, is exploring the idea of “upward falling payloads,” or pre-positioned containers or packages that lie on the ocean floor and wait until activated, at which time they “fall upward” into the water column to perform undersea missions, such as powering other unmanned systems. With some narrow exceptions, such as emplacement of seabed nuclear weapons or seabed mining, the use of the deep seabed is a high seas freedom enjoyed by all States. The more compelling question, however, is the extent foreign states may emplace naval devices or construct installations or structures on the continental shelf or within the EEZ of a coastal State for military purposes.

Article 56(1)(a) of UNCLOS provides that coastal States have certain “sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living….” in the EEZ. Coastal States also have “jurisdiction as provided for in the relevant provisions [of UNCLOS] with regard to “(i) the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations, and structures.” Under Article 60, coastal States enjoy the “exclusive right” to authorize or regulate the construction of structures, a rule that is extended to the continental shelf by virtue of Article 80. Coastal State jurisdiction over artificial islands and structures is not all encompassing, however, and is limited to jurisdiction “as provided for in the relevant provisions [of UNCLOS].” The relevant provisions of the EEZ, of course, relate principally to exclusive coastal State sovereign rights and jurisdiction over living and non-living resources in the EEZ and on the continental shelf, and not sovereignty over the airspace, water column, or the seabed.

In the recent Philippine-China Arbitration Award, the tribunal determined that China’s artificial island construction on Mischief Reef was an unlawful violation of Philippine sovereign rights and jurisdiction over its continental shelf. Since Mischief Reef is a LTE and not a natural island, it constituted part of the Philippine continental shelf and seabed of the EEZ. China failed to seek and receive Philippine authorization for its artificial island construction, and therefore violated Articles 56(1)(b)(i), 60(1), and 80 of UNCLOS (Arbitration Award, para. 1016).

Foreign States, however, are not forbidden to construct installations and structures on a coastal State’s continental shelf per se. Only those installations and structures that are “for the [economic] purposes provided for in article 56” or that “interfere with the exercise of the rights of the coastal State” over its resources require coastal State consent. (See Article 60(1)(b) and (c)).

But even if China converts its installations and structures into military platforms, their size and scope are so immense that they dramatically affect the quantity and quality of the living and non-living resources over which the Philippines has sovereign rights and jurisdiction. Although normally installations and structures that are built pursuant to military activities are not subject to coastal state consent, the industrial scale of Chinese activity lacks “due regard” for the rights and duties of the Philippines and its sovereign rights and jurisdiction over resources under Article 56 of UNCLOS.

If China had merely emplaced a small, unobtrusive military installation or structure on the seabed or landed an unmanned aerial vehicle at Mischief Reef as part of occasional military activities, it would not have been afoul of UNCLOS. Such incidental use of the seabed or an LTE (which is part of the seabed) are within the scope of permissible military activity in the same way as emplacement on the continental shelf of a small seabed military device. Foreign States may use the seabed for military installations and structures, and even artificial islands, as these purposes do not relate to exploring, exploiting, managing and conserving the natural resources. Only those military activities that rise to the level of or of sufficient are of such scale that they do not have “due regard” for the coastal state’s rights to living and non-living resources of the EEZ and continental shelf are impermissible.

The distinction is important because creation of the EEZ and recognition of coastal state sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the continental shelf was never envisioned to limit normal military activities. Current and future naval programs, in fact, may utilize a foreign coastal State’s seabed EEZ and continental shelf in a manner that is completely in accord with UNCLOS.

Where do we draw the line, however, between an insignificant presence and negligible interference that is lawful, and large-scale disruption that is unlawful? Like all legal doctrine, what constitutes genuine interference to coastal State sovereign rights and jurisdiction must be reasonable, i.e. not de minimis or trivial, but rather a substantial and apparent effect on the resources in the zone, as I discussed in Maritime Power and Law of the Sea. Emplacement of military devices or construction of military installations or structures in the EEZ and on the continental shelf of a coastal State must be judged by reasonableness, and not be of such scale or cross a threshold of effect that it interferes in a tangible or meaningful way with the coastal State’s resource rights.

China’s operation of military aircraft from a LTE is not a priori unlawful, any more than operation of military aircraft from a warship in the EEZ would be illegal. The reason that PLA Air Force military aircraft flights from the runway at Mischief Reef are objectionable and a violation of the Philippines’ coastal State rights is the magnitude of the activity and its effect on the living and non-living resources. Operation by a foreign warship of a small aerial vehicle that lands temporarily on an LTE, for example, would not be unlawful. Likewise, if a naval force emplaced a military payload inside a container and placed it on the seabed of the EEZ – that is, on the coastal State’s continental shelf – that would also be a lawful military activity.

James Kraska is Howard S. Levie Professor of International Law at the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law, U.S. Naval War College, Distinguished Fellow at the Law of the Sea Institute, University of California at Berkeley School of Law, and Senior Fellow, Center for Oceans Law and Policy, University of Virginia School of Law.

Featured Image: MARCH 10, 2016- Philippine Naval Ship, BRP Sierra Madre, sails near disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea (REUTERS/Erik De Castro)