What goals should the United States seek in the South China Sea? Trying to preserve the status quo – hoping that each country be ever content with its historic resources and territory – is simply unrealistic, as demographics alter populations and climate change alters fish stocks, river flows, and even the land under one’s feet, as sea levels rise. The U.S. feints at regional stability; yet advocating for peace while conducting military exercises with China’s neighbors, and arming those neighbors while proposing détente to their larger Pacific roommate, do nothing to turn down the temperature in an already overheated region.

Is there another way?

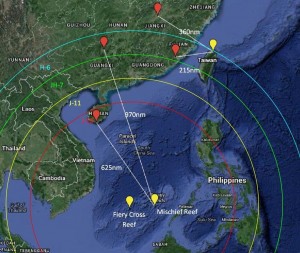

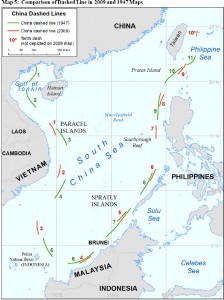

Interestingly, in response to China’s most recent provocative (or expansive, “salami-slicing”) efforts in the South China Sea, the affected countries have neither used, nor threatened, retaliatory military force. Perhaps they saw the lack of international military response to Russia’s actions in the Crimea and realized the futility of might against might, facing such a stronger force as China. Or perhaps they drew lessons from the international community’s decade-plus-long quagmire in the Middle East. At any rate, they went, instead, to the law, and to the United Nations, with the Philippines filing a 4,000-page case in March 2014, and Vietnam joining the case in early December. The case pends.

Chinese law is often seen by the Western world as a punitive weapon, wielded bluntly to reinforce the power of those with authority. I came face-to-face with this stereotype in 2010, when, aboard a U.S. Coast Guard high-endurance cutter, we hosted two Chinese shipriders from the Fisheries Law Enforcement Command (now part of the China Coast Guard), to cooperatively enforce an international moratorium on high-seas driftnet fishing. The shipriders’ knowledge of Pacific fisheries was extensive, and their insight into local fishing practices highly revealing; yet they were surprised by the professional and non-aggressive way we conducted fisheries boardings. Excessive force was unnecessary; the rule of law enabled us.

They were not the first shipriders I’ve met who were used to maritime law enforcement being far more aggressive in their home countries. The FLEC shipriders were fascinated to learn that the law not only empowered, but also restrained us: that it protected citizens’ rights, and even the rights of non-citizens. This is powerful.

Whence the origins of Chinese law? The legal tradition in China has grown, over centuries, from two roots: Legalism, which results in the often brutal applications of punishment seen in Western media; and, curiously, Confucian philosophy. While Legalism posits tough laws and harsh sentences to keep the populace controlled, Confucianism holds that laws should help a community achieve harmony (or “Li”); and that leaders are expected, by virtue of their status, to model the moral behaviors they want their people to emulate. This Confucian strain in Chinese thought provides an interesting and useful opening for influencing development in a new direction, toward a cooperative and harmonious maritime code of conduct in the Pacific.

How might China be convinced to develop such a code? After all, they are stronger than their neighbors: why handicap themselves? Yet economics suggests that selfish or destructive behaviors net a country less long-term economic growth and geopolitical power than mutually beneficial international actions.[1] This is the angle to play, enhanced by emphasizing the inherently Chinese flavor of a Confucian-based legal code. China has much to benefit by spending less on a military arms race and more on economic development: by cultivating harmonious relationships with their neighbors, they will create a stronger and more willing market for their goods, to keep driving the massive yet near-solitary economic growth engine keeping their political party empowered.

This is, perhaps, an audacious proposal, for it seeks through persuasion and a bit of flattery to encourage China to become a responsible maritime actor, on its own terms, by appealing to its history and pride. The U.S. could say: We can help you develop a comprehensive Pacific maritime legal framework; China-led, Confucian-based, for harmonious interaction with your neighbors and comprehensive regional prosperity.

Overly optimistic? Not impossible.

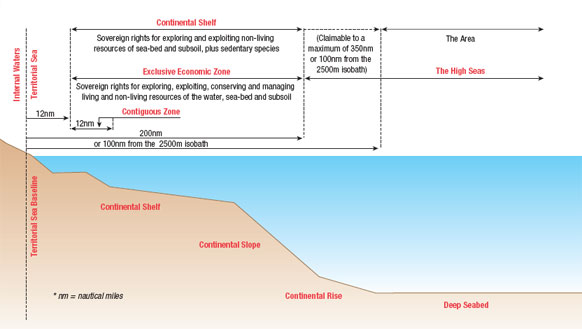

It is important here to focus not just on maritime law tactics (how to conduct a law enforcement boarding; how to apply various levels of force) but on strategy: how to build a framework for long-term, harmonious international maritime interaction. This could start at the military-to-military level, through engagements between China Coast Guard and U.S. Coast Guard counterparts. China Coast Guard leaders would be invited to observe, not only tactical-level boardings and operational-level maritime law enforcement planning; but also the legal aspects of preparing case packages, reviewing case law, and arguing cases in U.S. court. Discussions would cover both strengths and shortfalls of the existing U.S. and international maritime legal systems, expanding to cover differences between the type of maritime law enforcement the U.S. Coast Guard conducts, and the similar-but-different, non-law enforcement Maritime Interdiction Operations (MIO) conducted by both the U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard to enforce UN resolutions. What elements of each should be integrated into a Pacific maritime “code of conduct”?

One of the benefits of a Confucian-based code of conduct for South China Sea ship interactions would be to assume all parties’ good intentions, rather than their ill-will. In a specific maritime rulebook supporting this code, potentially aggressive actions would be presumed, unless meeting certain hostile tripwires, to be honest mistakes, prompting mutual retreat. Furthermore, in order to discourage intentional “gray area” behavior, the tripwires would specifically reflect hostile intent – regardless of whether a military or civilian actor cross them.

Additionally, again based on Confucian philosophy, the greater the power, the more the responsibility to model ideal behavior. Thus, as the leading power in the region, the onus is on China to set the most moral and harmonious example in its maritime interactions.

This code of conduct would both complement, and expand upon, the existing COLREGS: for where the COLREGS guide navigational interactions, the expanded code of conduct would also cover “exploratory interactions” – when ships are not simply navigating from one port to another, but exploring, patrolling, conducting research, or otherwise operating intentionally but non-navigationally.

Concurrent U.S. Defense-State strategic regional engagement is also recommended, in which reductions in maritime tensions are coupled with increased diplomatic development, where the U.S. encourages countries with competing resource claims to develop bilateral or multilateral agreements for resource sharing and protection. The goal is to convince Pacific nations that sharing the pie doesn’t mean going hungry: instead, cooperation can reduce each country’s individual share of defense and production, while promoting labor specialization and national pride.[2] As a bonus for regional stability, the more countries invested cooperatively in an area, the greater their individual and collective desire to avoid any sort of conflict that might harm those resources, or take their production off-line.

Both the U.S. combatant commander and his country team counterparts should cooperatively emphasize Chinese-influenced, Confucian-based legal bases throughout the spectrum of their “defense, diplomacy, and development” engagements, as an overarching strategic theme. This is one way the U.S. can face China down in their game of “Go”:[3] from every angle, at every opportunity, seeds of a harmonious rule of law will be planted. While some efforts will be stymied or stifled, some seeds will grow, and ideally, this concept of law will begin to permeate Chinese society deeply enough that it cannot quickly be uprooted. And why should the Chinese tear it out? It will underpin their economic growth, protect their military from engagement, and cement their moral status as a 21st-century great power.

Engagement surrounding the rule of law is a long-range play. The goal is not only a more peaceful, China-influenced, legal framework for the Pacific; but also to sow seeds of change for democratic evolution within China itself. Raising awareness within Chinese leadership that laws are not just sticks with which to beat opponents, but beacons of moral empowerment; that laws should guide leaders to act justly; that the rule of law can inspire a peaceful, communal patriotism; and that people at all levels of society can trust the law to protect them – these powerful democratic concepts can, over time, drive significant positive change within Chinese society: change that traditional military might not and political posturing never could achieve.

Facilitating a China-led, Confucian based, cooperative maritime-based rule of law could eventually be expanded to other contentious and competitive domains, including space, cyberspace, and even intellectual property – all areas that could benefit from an improved, shared, legal basis. And perhaps, success in this region of the world could be expanded to locally-led and -derived, rule-of-law-based engagements in other combative areas. After having seen such conflict and destruction on its many shores, we could at last look forward to a new era in which the Pacific is finally peaceful enough to be worthy of its name.

Lt. Heather Bacon-Shone serves in the United States Coast Guard, and has operational afloat experience throughout the Pacific. The views expressed herein are those of the author and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the U.S. Coast Guard or Department of Defense.

[1] In economic terms, rent-seeking versus profit-seeking.

[2] In other words, a non-zero-sum game.

[3] “To update an old saying, ‘Russians play chess, Chinese play “go,” and Americans play poker.” In Reveron, Derek S. and James L. Cook. “Developing Strategists: Translating National Strategy into Theater Strategy,” Joint Force Quarterly, Issue 55, 4th Quarter 2009, p. 21.