By Joelle Westlund

In some ways overshadowed by events elsewhere in its maritime claims, China added fuel the regional fire that has characterized its relations with neighbouring states for the last several decades on July 10th. This time it did so by launching a naval exercise in the waters near the Zhoushan islands in the East China Sea. The maneuver comes as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) placed a ban on shipping and fishing vessels entering the designated exercise area. The CCP have chosen a heated time to send the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and Navy to practice its ability to operate in contested waters. But the timing of this maneuver was far from fortuitous.

The exercise in the Zhoushan has been interpreted as a demonstration of China’s ability to specifically counter the claims on another set of islands in the East China Sea – Diaoyu in Chinese and Senkaku in Japanese – that have been at the center of an ongoing row between China, Taiwan, and Japan. The territorial dispute over the islands recently resurfaced when Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda offered to purchase the chain of islands from their private owners. University of Tokyo professor Akio Takahara pointed out that the offer was submitted in an attempt to “stabilize the situation […] not to escalate the situation.” Logistically, Japan’s acquisition of the island makes sense, given that its central government rents the three islands and keeps them protected through landing restrictions and access to nearby waters. Beijing’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Weimin responded curtly to the proposition by stating, “China’s holy territory is not ‘up for sale’ to anyone.” State-owned news agency, China Daily called for “more aggressive measures to safeguard its territorial integrity […] Should Japan continue to make provocative moves.”

The disputed islands are not the only quarrel in which China finds itself. The Asian superpower is currently locked in a wrangle with Vietnam and the Philippines over the Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea. Sovereignty claims to the islands are touchy since the islands are believed to provide rich fishing grounds and potentially huge oil and gas reserves. The situation has escalated since the beginning of April when Chinese civilian vessels found themselves in a standoff with the Philippines Coast Guard. Chinese embassy spokesman Zhang Hua stated, “The Chinese side has been urging the Philippine side to take measures to de-escalate the situation.” In response Philippine President Benigno Aquino ordered the withdrawal of its government vessels in “hope[s] this action will help ease the tension.” China, however, has yet to do the same as it still has seven maritime vessels encircling the Shoal and has rejected attempts to resolve the tiff through the employment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, as recommended by officials of Vietnam and the Philippines.

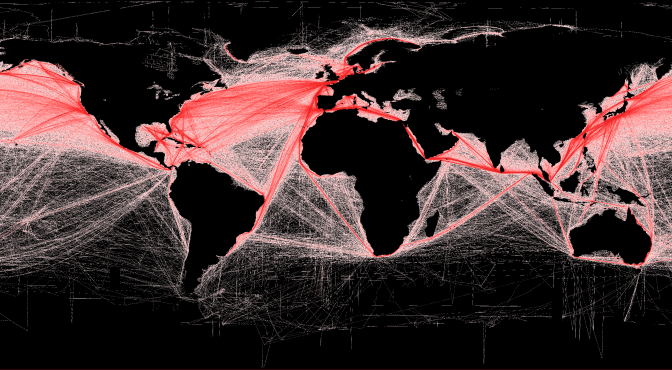

China is well versed in threatening navigational freedom in territorial waters, making countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia weary, since China appears to have set its sights on the Malacca Strait. The Strait is one of the most critical maritime choke points as over 1,000 ships a day pass through its channels that link the Pacific to the Indian Ocean. At the 10th Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, China’s Minister of Defence Liang Guanglie called for China to take a more active role over the management of the Strait of Malacca. For China, which relies on nearly 80 percent of its crude oil imports from the Middle East and Africa, security of the passage is crucial and military involvement offers the opportunity to mitigate terrorist and insurgency risks in the lanes.

But given China’s aggressive posture adopted towards its neighbours, expansion into the Strait warrants concern and suspicion from regional powers. Exactly how states should tackle China’s multiple squabbles dominated discussion among senior diplomats at ASEAN’s latest meeting in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations has continued to look to the United States to increase its role in the area to minimize tension and this year’s gathering echoed a similar appeal. China however, has expressed its distaste for U.S. involvement and “hyping” of the dispute, arguing, “This South China Sea issue is not an issue between China and the U.S. because the U.S. doesn’t have claims over the South China Sea.”

A Role for Canada

To many Asian states, Canada represents an affluent and pluralistic country ripe with opportunity. Its diplomatic engagement in the region has predominately played a supportive and capacity-building role in maritime security initiatives. Canada has sought to expand its role in the area militarily and economically, and has done so most recently with Canadian Defence Minister Peter MacKay’s trip to Singapore. MacKay spent the weekend in talks with Asian defence ministers regarding the enlargement of a Canadian presence and toured potential sites for a ‘hub’ for Canadian military operations. 1,400 Canadian sailors, soldiers, and air force personnel will also be taking part in the biannual ‘Rim of the Pacific’ military exercises held from June 29 to August 3.

This involvement represents an important opportunity for Canada to demonstrate its commitment to the region, but even still, there needs to be a more concrete diplomatic engagement to secure relations. With announcements like U.S. Defence Secretary Leon Panetta’s latest statement that 60 percent of the U.S. Navy fleet will be stationed in the Pacific by 2020, Canada must to buff up its presences before it loses out.

The disputes over the South China Sea, the Scarborough Shoal and the potential strain over the Malacca Strait, opens the door for Canada’s involvement. James Manicom of The Globe and Mailargues that Canada can use its status as an impartial dialogue partner to engage in regional track-two diplomacy. If Canada hopes to expand its economic relations in the region, such engagement outlined by Manicom is necessary. Canada currently stands as the ASEAN’s ninth largest investor and 13th largest trading partner, totaling over $1.6 and $9.8 billion, respectively. The Harper government needs to ditch the reluctance that has defined Canada-Asia relations and push for a peaceful resolution of the current disputes with China. Doing so would allow Canada to gain credibility in the region and supplement U.S.-Japanese-Philippine calls for stability. Further, as China continues its somewhat predacious behavior towards its neighbours, Canada can reassert itself as an agent of peace and diplomacy in the region.

Joelle Westlund is an Asia-Pacific Policy Analyst at The Atlantic Council of Canada. She is currently working towards a Master’s Degree in Political Science at the University of Toronto. Joelle holds a Bachelor’s Degree in International Relations from the University of Toronto and has studied at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic as well as the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Any views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and the news agencies and do not necessarily represent those of the Atlantic Council of Canada. This article is published for information purposes only.

Blog cross-posted with our partners at the Atlantic Council of Canada