When discussing China’s strategy in the South China Sea it is first necessary to begin by asserting that there is in fact a strategy, which is readily discernible from public documents and pronouncements. There has been some disagreement over the degree of coordination between operational units and the central government,[1] with some analysts questioning if Beijing actually has a strategy in these areas,[2] while others have contended that China does in fact have a strategy that it regards as increasingly successful in achieving its desired objectives. According to Peter Dutton, the Director of the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) at the U.S. Naval War College, this strategy is centered on the use of “non-militarized coercion” that has provided a means for controlled escalation.[3]

While the execution of this strategy may have at times in the past been poorly implemented due to the vague and developing nature of China’s strategic goals, there has been a concerted effort since and even before Xi Jinping came into power to at least increase coordination and oversight, if not clarify the strategic objectives themselves. This increased coordination and oversight is however primarily intended to better control the potential for escalation, and is part of a wider-evolving Chinese strategy to better protect what it views as its “maritime rights and interests” in the South China Sea. These new objectives do little more than consolidate previous strategic guidance, suggesting that existing patterns of expanded Chinese maritime presence and corresponding incidents at sea are more likely to persist than diminish in the years ahead, though they may be managed more closely by Beijing.

Since 2007 Chinese maritime law enforcement (MLE) agencies have been conducting what were termed “rights protection” (weiquan) missions in the South China Sea,[4] which slowly expanded in number and intensity over time, leading to an increase in operational confrontations and incidents at sea between not only China and its neighbors, but also the United States. This shift in tactics was readily evident in the composition of Chinese forces involved in these confrontations: where previously PLA-Navy forces had been primarily involved, according to a report by the U.S. Center for Naval Analysis (CNA), by 2009 the majority involved Chinese MLE agencies.[5]

While it is not known if the “rights protection” missions were at the time approved by key decision making bodies such as the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) or the Central Military Commission (CMC), a number of recent developments suggest that they were at some point subsequently approved at the highest levels of the Chinese government and are likely to form a central focus of Chinese strategy going forward. The work report of the 18th Party Congress at which the Chinese leadership transition occurred, defined China for the first time as a “maritime power,” one that will “firmly uphold its maritime rights and interests.”[6] Work reports from the Party Congress play a central role in determining the character and content of Chinese strategy going forward,[7] and the work report from the most recent would suggest that not only does China increasingly see itself as a maritime power, but that maritime “rights protection” missions will increasingly become a central component of China’s approach in the South China Sea (SCS).

Important institutional changes in line with these objectives had already begun to be implemented even before the Party Congress occurred, with the central leadership creating several leading small groups to oversee and improve coordination of maritime rights protection in the SCS. The Maritime Rights Office, a leading small group now headed by Xi Jinping, was created in 2012 reportedly to “coordinate agencies within China.”[8] The Maritime Rights Office falls under the Foreign Affairs Leading Small Group (FALSG), which is ‘widely believed to be the central policy making group’ in the Chinese Party apparatus. According to Bonnie Glaser, an analyst at the Center for International and Strategic Studies (CSIS), the Maritime Rights Office includes “over 10 representatives from various units, including several from the PLA,” and is in charge of implementing guidelines handed down by the PBSC.[9] During the same talk, Ms. Glaser also noted the existence of a second leading small group, created specifically to handle issues in the South China Sea, which is also now headed by Xi Jinping.

That there had already been a discernible push by the central leadership in Beijing to improve coordination and oversight before the incident off the Natunas in March of 2013 calls into question analysis suggesting that a lack of coordination or oversight from Beijing is the central factor explaining Chinese behavior in the South China Sea. But this has never been as sufficient an explanation as some have implied, and it seems increasingly plausible that Beijing’s behavior can better be explained as part of a broader strategy. This strategy is evident in the decision of the central leadership to expand and utilize Chinese MLE agencies to more assertively protect what China considers to be its maritime rights and interests in disputed areas, often through the use of non-militarized coercion.

This non-militarized coercion includes not only deterrent but also compellent dimensions, as was clearly demonstrated in the recent incidents involving Indonesia. Attempts by China to compel its neighbors into accepting its ‘historic rights’ in the SCS pose a potential threat to the international rules and norms embodied in UNCLOS, and to the extent that China’s “maritime rights and interests” are defined based on historical rather than legal grounds, an implicit challenge to the status quo.

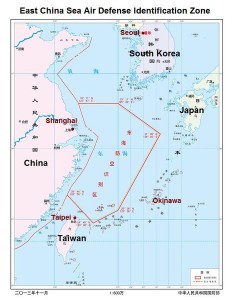

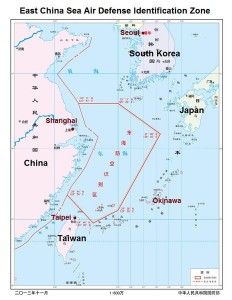

While a more militarized approach by China in the East China Sea has become increasingly evident with the recent creation of the Chinese Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) there,[10] the non-military and military instruments of power have always been closely intertwined in Beijing’s evolving strategy. Military power has long been more visible in the ECS disputes, with serious incidents occurring involving naval vessels there.[11] At the same time however, China has been systematically and proactively asserting maritime jurisdiction through an enlarged and more aggressive MLE presence around the Senkakus, in an effort to ‘establish a new reality on the sea,’ as Scott Cheney-Peters of CIMSEC put it.[12]

In addition to the Maritime Rights Office, Xi also became head of the “Office to respond to the Diaoyu (or Senkaku) Crisis” when it was created in September 2012, as part of the wider effort to increase coordination and institutional oversight.[13] According to reports there is solid evidence, including ‘from electronic intercepts’, indicating that “the movements of Chinese boats and ships were micromanaged by the new taskforce chaired by Xi.”[14] If accurate, these reports would provide conclusive evidence that Chinese actions in disputed areas of the East and South China Seas are in fact being directed and closely managed from Beijing as part of a wider strategy.

What might be viewed as two separate programs, military and civilian, are actually designed to be complementary parts of the same effort to protect China’s claims in areas like the South China Sea, with the MLE agencies playing the lead while reinforced in the background by the presence of much more capable naval warfighting platforms. Ties between the State Oceanic Administration (SOA) and the PLAN are close and longstanding,[15] and can be expected to strengthen in the future with the creation of the new China Coast Guard under SOA. The fact that military assets have taken a more prominent role in the disputes over the Senkakus suggests that the military and non-military means of coercion are part of a continuum of Chinese strategic options to exert leverage over other claimants to the disputes, to be used in accordance with the various operational responses of those claimant countries.

This could provide important lessons for claimants in Southeast Asia, where non-military forms of coercion are likely deemed sufficient by China to achieve its desired goals at present. Should this later prove to no longer be the case, perhaps after countries like Vietnam build up their own MLE forces (which they are in process of doing), Southeast Asia might also come to expect more militarized forms of coercion to begin stretching further south into the SCS. It is not lost on ASEAN that when declaring its ADIZ over the ECS China reserved the right to create additional ADIZ’s in the future, possibly in the South China Sea.[16] The fact that this announcement occurred almost simultaneously with the first deployment of China’s new aircraft carrier to the SCS was viewed with concern in the Philippines, where Foreign Secretary Del Rosario stated that there was a “threat that China will control the airspace (in the South China Sea).”[17]

While China may truly see its actions in a reactive or defensive light, others are unlikely to share this perception and may very well interpret more offensive intentions based on China’s own definition of the status quo, as well as its attempt to enforce it through coercive means. So long as China refuses to take into account the credible concerns of its neighbours and persists in carrying out its current strategy in the South China Sea, the disputes are likely to remain China’s “Achilles heel” in Southeast Asia,[18] and could constrain its larger diplomatic initiatives in the region. Along with the disputes will also remain the danger that misperception or miscalculation could render escalation less controllable in future incidents, a distinct possibility that seems destined to become more pronounced if the various means of coercion continue to evolve in an increasingly militarized direction.

Scott Bentley is an American PhD candidate at the Australian Defence Force Academy.

This post appeared in its original form at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s The Strategist.

————————————————————————————————————

1. ICG Report. “Stirring Up the South China Sea (I),” Asia Report No. 223, 23 April 2012. Available online at http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/asia/north-east-asia/china/223-stirring-up-the-south-china-sea-i.aspx

2. Lyle Goldstein. “Chinese Naval Strategy in the South China Sea: An Abundance of Noise and Smoke, but Little Fire,” Contemporary Southeast Asia Vol. 33, No. 3 (2011), p. 320-347

3. http://csis.org/files/attachments/130606_Dutton_ConferencePaper.pdf

4. NIDS China Security Report 2011. Tokyo: National Institute of Defense Studies, p. 7. http://www.nids.go.jp/english/publication/chinareport/pdf/china_report_EN_web_2011_A01.pdf,

5. George P. Vance. “The Role of China’s Civil Maritime Forces in the South China Sea,” Center for Naval Analysis (CNA) Maritime Asia Project, Workshop Two: Naval Developments in Asia, August 2012, p. 103

http://belfercenter.hks.harvard.edu/files/cna-naval-developments-in-asia-report.pdf

6. Heath, Timothy. “The 18th Party Congress Work Report: Policy Blueprint for the Xi Administration,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief Volume: 12 Issue: 23; November 30, 2012 http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=40182&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=25&cHash=de4e16aa5513509eb1c0212ac6e401e4

7. Heath, Timothy. “What Does China Want: Discerning the PRC’s National Strategy,” Asian Security, 8:1, 54-72. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14799855.2011.652024#preview

8. Jane Perlez. “Dispute Flares Over Energy in South China Sea,” NY Times. December 4, 2012 http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/05/world/asia/china-vietnam-and-india-fight-over-energy-exploration-in-south-china-sea.html?ref=world

9. Bonnie Glaser. Remarks at Brookings Institution, December 17, 2012. Panel 1 on “United States, China, and Maritime Asia.” Remarks (15:00-18:00) available at- http://www.brookings.edu/events/2012/12/17-china-maritime

10. http://thediplomat.com/2013/11/china-imposes-restrictions-on-air-space-over-senkaku-islands/

11. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/06/world/asia/japan-china-islands-dispute.html?hp&_r=0

12. https://cimsec.org/keeping-up-with-the-senkakus-china-establishing-a-new-reality-on-the-ground-er-sea/

13. http://lowyinstitute.org/publications/chinas-foreign-policy-dilemma

14. http://www.smh.com.au/world/all-the-toys-but-can-china-fight-20130426-2ikmm.html

15. http://news.usni.org/2013/11/25/clash-naval-power-asia-pacific

16. http://www.scribd.com/doc/188285766/Thayer-China-s-Air-Defence-Identification-Zone

17. http://globalnation.inquirer.net/92583/philippines-fears-china-wants-west-ph-sea-air-control

18. http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-achilles-heel-in-southeast-asia/