By CDR (ret.) Dr. Eyal Pinko

Introduction

“Hezbollah has the best missile boats in the world. He has many missiles, but he can’t drown.”—Major General Eli Sharvit, Israeli Navy Commander, January 2018

Navies increasingly must deal with asymmetric naval forces, whether they are terrorist organizations’ naval forces, pirates, or asymmetric naval forces operated by countries as part of a comprehensive and integrated naval strategy. This integration is seen in the Chinese Navy with its maritime militia and missile boat force, as well as the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Navy which operates alongside the regular Iranian Navy.

The characteristics of asymmetric naval warfare, including its force development, civilian integration, and combat doctrine of multidimensional attacks or gray zone operations, poses many challenges to navies. This is especially true for those naval intelligence organizations assigned to understand these asymmetric forces and their methods.

Naval intelligence organizations seeking to understand asymmetrical naval forces must promote a culture of creativity, daring, pluralism, and deep cultural knowledge in order to best understand how the asymmetric adversary behaves and operates. One pertinent example of how naval intelligence was stressed against asymmetric naval forces can be found in the Israeli’s Navy’s experience against Hezbollah in the Second Lebanon War.

The Second Lebanon War at Sea

On July 12, 2006, Hezbollah, the Lebanese terror organization, launched a surprise offensive attack against an Israeli Defense Force (IDF) unit guarding and patrolling Israel’s northern border. The Hezbollah force killed three Israeli soldiers and captured two other soldiers. At the same time, Hezbollah fired rockets toward northern Israeli cities. The IDF decided to respond unexpectedly. And so the Second Lebanon War broke out without warning.

During the war the Israeli Navy was assigned several missions. The missile boat flotilla carried out several essential roles, including intelligence gathering, naval gunfire support, missile attacks against significant targets on the Lebanese coast, and as artillery support to Israeli ground forces. The submarine flotilla carried out special operations, and the 13th flotilla, the Naval Commandos, carried out assault operations from the sea to the Lebanese coast. The Navy’s most important mission was to impose a naval blockade on Lebanese shores and prevent maritime trade.

On Friday, July 14, at 8:42 PM, Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah burst onto the air. With a video running in the background, he excitedly recounted that his organization attacked an Israeli Navy missile boat sailing off Beirut’s coast and that the Israeli missile boat was drowning.

A day later, it became clear that the Lebanese terrorist organization’s naval force, with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Quds Force’s help, fired a C-802 anti-ship missile at Israeli missile boats. One of the missiles hit the crane of the INS Hanit, which the ship managed to survive, return by tow to its homeport, and sail again after about three weeks for operational missions. However, four Israeli crewmembers lost their lives.

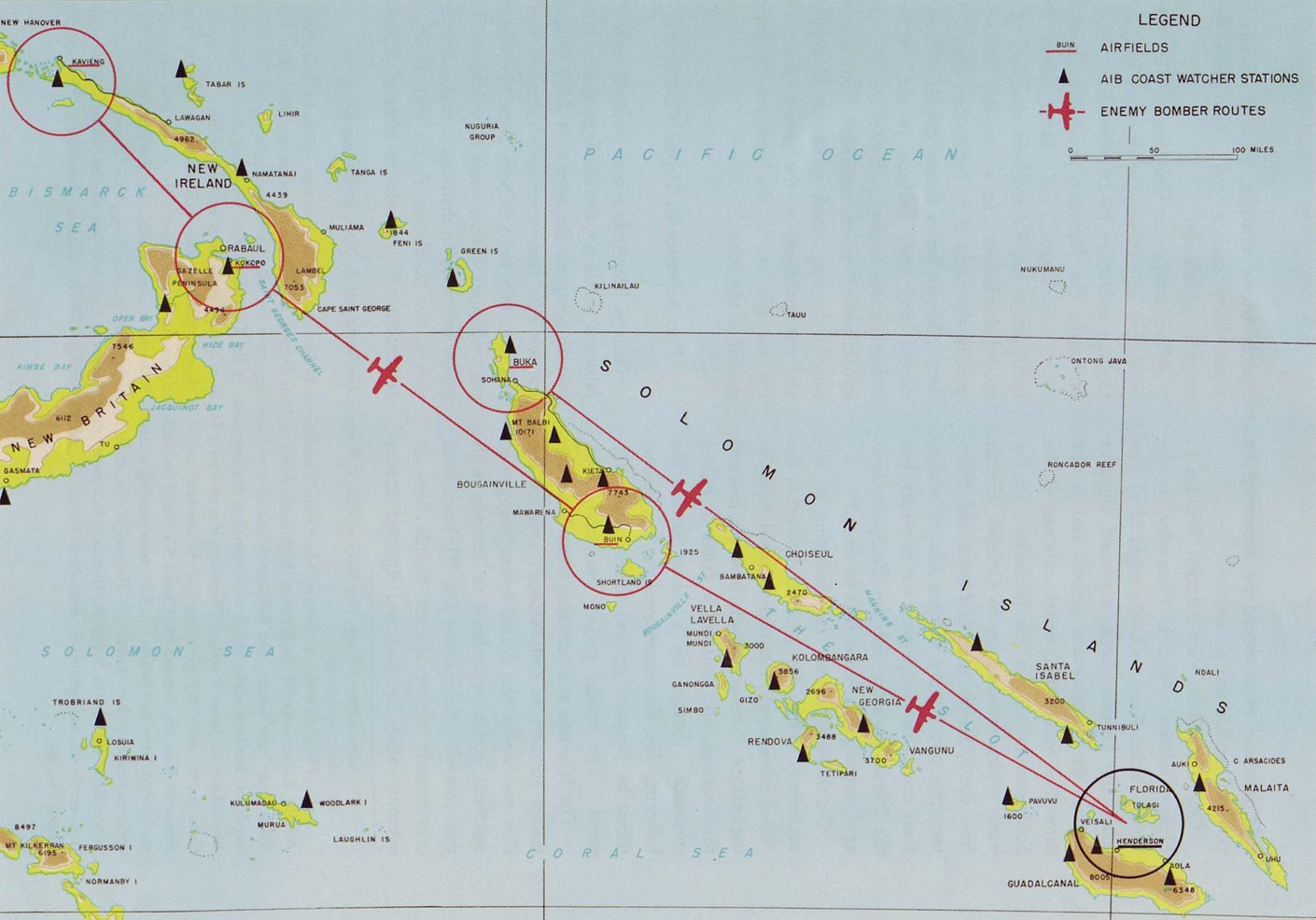

Intelligence details regarding Iranian anti-ship missiles delivered to Hezbollah were being collected by the Israeli intelligence agencies about two years before the ship was hit. However, the assessment of naval intelligence in 2004 was that rockets had reached Hezbollah’s naval force (not missiles), and it estimated that Hezbollah would attempt to detect Israeli Navy ships using an array of coastal radars and fire the rockets at them.

A better understanding of the nature of asymmetric naval warfare and its associated force development could have better prepared the Israeli Navy for this attack. However, naval asymmetric warfare poses unique complexities that can strain the ability of naval intelligence to comprehend it.

Naval Asymmetric Warfare

Naval asymmetric warfare is warfare conducted at sea and from the sea, between two adversaries, one of whom has a significant superiority over the other in quantity, quality, combat doctrine, or technology. Asymmetric naval warfare is usually employed by the weaker side to challenge the maneuvering, warfighting, and command and control capabilities of the stronger side, therefore enabling the weaker side to offset the stronger side’s conventional superiority.

Asymmetric naval warfare is based on several principles:

Passive warfare: A set of complementary efforts and means which do not necessarily include combat or the use of combat systems, that will prevent losses to equipment, damage to infrastructure (civilian and military), and will prevent as much personal injury as possible. Passive warfare can include the use of deception, psychological warfare, and cyber warfare.

Assimilation: Employing nontraditional combatant platforms and means and integrating them into civilian infrastructure (such as civilian fishing boats or innocent civilian fishing ports). This can include embedding combat operatives among the civilian population.

Swarm attack tactics: Swarm attacks are based on attacking a target with numerous attacking vessels from different directions, simultaneously and multidimensionally. The multidimensional attack can feature surface, subsurface, aerial, and shore-based attacks, and be carried out by employing missiles and rockets, naval mines, torpedoes, unmanned aerial vehicles, and more. Swarm attacks attempt to impose a saturation dilemma on the target’s defenses, where the attacked vessel’s ability to defend itself is disrupted in a manner that may be out of proportion to the threat itself, because of how the threat is presented. The asymmetric force secures temporary warfighting advantages by concentrating for swarm attacks and then subsequently disperses to mitigate exposure to counter responses.

The use of maritime topography: Topographical features such as coastal routes, coves, inlets, islands and more can be used to hide, conceal, resupply, insert special operations forces, and generally operate against the opponent.

Expansive target sets: The asymmetric naval force will often operate against both military and civilian infrastructure, such as oil platforms and seaborne economic assets.

Hezbollah’s Asymmetric Warfare

Hezbollah’s naval force was established several years before the Second Lebanon War in 2006, but began to develop significantly after the Israeli Navy ship was hit. Naval force development was further accelerated by an understanding that fighting in the maritime dimension has significant implications for a future battlespace in Lebanon, on Israeli force maneuvering at sea and on land, and the Israeli homefront capability to continue prolonged fighting.

The Iranian Revolutionary Guards Quds Force was the entity who helped set up the Hezbollah naval unit, worked to equip it with quality Iranian naval weapons, and trained the unit in Iranian Revolutionary Guards bases and training camps. An Iranian officer described Hezbollah’s naval unit capabilities and said it has a team of naval commando divers and Chinese-made speedboats trained to attack Israeli navy ships through Iranian swarm attack tactics. Another potential operational mode is the use of high-speed boats to carry out suicide attacks on Israeli vessels.

The Iranian officer added that Hezbollah enlisted Iranian and North Korean experts to build a 25-kilometer-long defensive strip along the Lebanese shore. Underground outposts were constructed, connected by canals, and allowed easy and quick passage from one position to another. This infrastructure enables Hezbollah to operate and execute combined attacks from different directions, to move information and weapons from place to place, all while defending itself by hiding in the folds of the ground and beneath it.

The Revolutionary Guards built warehouses for Hezbollah in the Bekaa area of eastern Lebanon, where rockets, missiles, and ammunition are stored. The warehouses, managed by Revolutionary Guards officers and Hezbollah operatives, enable all Hezbollah units, including the naval force, to have a continuous supply of weapons and access to the logistical and technological backbone.

The force development of the organization’s naval arm is based on insights and lessons learned by Hezbollah with the help of Iran (especially lessons learned from the First Lebanon War (1982), the Second Lebanon War (2006), and the IDF’s military operations in the Gaza Strip. Hezbollah and Iran understood the IDF and Israel’s vulnerabilities, mainly Israel’s strategic infrastructure vulnerabilities (at sea and on the coastline), including gas rigs, ammonia storage facilities, seaports, energy facilities, water desalination plants, and more.

Moreover, the Israeli Navy ship hit during the Second Lebanese War, and the fact that the Israeli Navy subsequently removed its ships from the Lebanese coastal area, was perceived by Hezbollah as a groundbreaking event that disrupted Israeli naval operations and perceptions. Hezbollah understood that if its missiles hit ships (whether naval or merchant ships), this would inhibit seaborne commercial movement to and from Israel. This could create a naval blockade and a state of sea denial which Israel would not be able to tolerate in the long run.

According to those insights, Hezbollah began to strengthen its naval forces, building long-range detection capabilities, coastal missile batteries, and well-developed naval commando forces. The coastal missile batteries, including the 300-km Russian long-range Yakhont missiles, which were apparently transferred from the Syrian Navy (with or without the knowledge of Russia) and the Iranian coastal anti-ship missiles of various models and ranges (such as Noor, Gahder, Ghadir, and C-802 missiles), enable Hezbollah in future armed conflicts to hit Israeli naval ships operating off the coast of Lebanon. More than that, some of these capabilities will enable Hezbollah to hit the ports of Haifa and Ashdod within missile range, and even Israel’s gas infrastructure, therefore moving the campaign into Israeli territory. A naval blockade on its ports would disrupt maritime commerce routes to and from Israel and paralyze its energy supplies.

https://gfycat.com/circularfearlessdeermouse

A maritime barrier constructed north of Gaza to guard against infiltration by Hamas naval commandos. (Footage via Haaretz/Israel Ministry of Defense)

Beyond the naval blockade and sea denial capabilities, the Hezbollah naval unit under Iranian auspices is developing capabilities to carry out seaborne commando raids and sea mine attacks on Israeli ports using Iranian midget submarines and diver transportation vehicles. These can be launched from Hezbollah’s permanent bases along the Lebanese coast or even through merchant ships.

During the 2011 Syrian campaign, Hezbollah’s naval forces, along with Syrian and Iranian Revolutionary Guards naval forces, were stationed in the Syrian city of Ladqiya with fast patrol boats. These could be used if necessary to attack rebel forces and against Israel in case of direct Israeli intervention in the Syrian campaign.

In summary, Hezbollah’s asymmetric naval force is developing in several dimensions:

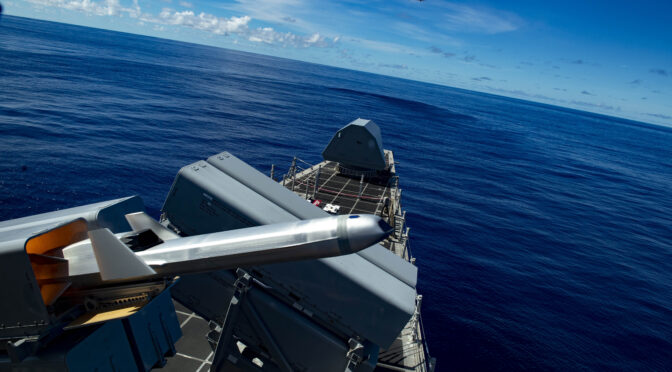

- Coastal launched long-range anti-ship missiles. Some of these missiles can also be used against seaports, coastal infrastructure, and gas rigs.

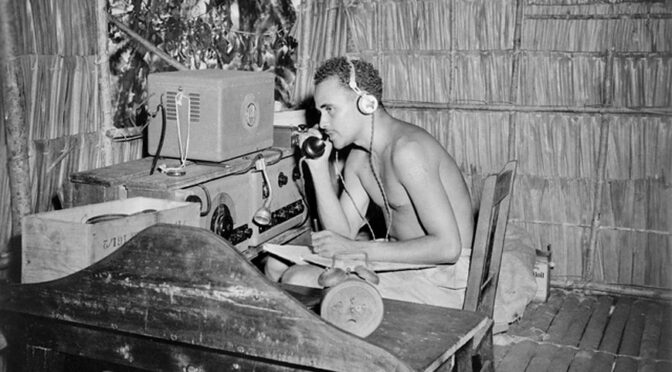

- The development of detection measures and intelligence systems enables the missile operators to build a real-time and accurate maritime operating picture that will be used to identify and mark targets for a missile attack.

- Rapid attack capabilities using high-speed boats, enabling the naval unit to carry out commando operations, attack Israeli ships, gather intelligence, and attack strategic infrastructure.

- Unmanned surface and undersea vehicles for intelligence collection operations and suicide attacks.

- Undersea warfare capabilities, including midget submarines and SDVs (Swimmers Delivery Vehicles).

The Role of Naval Intelligence

The role of naval intelligence is to formulate and present an intelligence picture about rivals and activities in the maritime arena. Naval intelligence provides a strategic and tactical intelligence picture, enabling decision-makers and operational units to make decisions regarding force development, combat doctrine, force allocation, operations, and defining ongoing missions. Naval intelligence is required to present an intelligence picture, based on processes of collection, evaluation, research, and assimilation on several levels.

Opponents’ capabilities and infrastructure: Technological intelligence focuses on the opponent’s combat systems capabilities, performance, parameters, advantages, and vulnerabilities, along with the number of combat systems in the opponent’s possession and its procurement and force development processes. This intelligence also includes information about the opponent’s combat systems’ level of maintenance, readiness, and operational competence. Technological intelligence and the assessment of the opponents’ capabilities influence the strategic processes of force development, procurement, and developing combat doctrines.

The opponent’s intentions: Strategic intelligence can focus on the opponent’s intentions and propensities to launch military campaigns, offensive actions, and proliferate weapons. This intelligence can allow the operating forces to receive an early warning about the opponent’s operational activity and set in motion a preventive or defensive response.

Operations Intelligence: Tactical and operational intelligence can support planning and executing peacetime operations, operations between military campaigns, or during them. Operational naval intelligence is required to support sea operations (at sea and from the sea), including surface operations, submarine operations, unmanned aerial vehicle employment, and special commando operations. This intelligence includes target intelligence, enabling one to identify an opponent’s units’ infrastructure, headquarters, and operations, which may be targeted for attacks.

Exposure Intelligence: Intelligence can help one appreciate the exposure of one’s own forces’ during operational activities, technological capabilities, force development processes, combat doctrine, and other information. Such intelligence is required as a decision-making support tool in carrying out naval operations to minimize force exposure and prevent casualties. It is also used to develop strategic and tactical options for deception operations.

Naval Intelligence Challenges in the Face of Asymmetric Forces

Asymmetrical naval forces impose several significant challenges on naval intelligence. The first challenge is the collection challenge, which includes efforts to gather information about asymmetric naval forces at the strategic and tactical levels.

At the strategic level, an intelligence challenge is to understand force development and procurement. The force development efforts of regular navies are usually visible to an extent to the public and through open-source media. But for asymmetric naval forces, force development is usually covert and clandestine. Weapons are secretively procured, and identifying covert proliferation is a significant challenge, without which it is not possible to build ideal responses and operational plans. Without intelligence on proliferation actions cannot be to thwart and stop deliveries. The entities that deliver these weapons and the related training, whether they be arms traffickers or state-affiliated actors like the Quds Force, often take extensive measures to conceal their deliveries and associations.

Moreover, technological intelligence regarding the performance and capabilities of combat systems in the hands of the asymmetric opponent requires not only very complex continuous intelligence gathering, but also profound and intimate research, including understanding of the technological limitations of the opponent’s combat systems, especially when software-based combat systems can be modified or upgraded. Technological intelligence makes it possible to examine the capability of electronic warfare systems and hard-kill defense systems to defend against present and future threats that the asymmetric adversary is likely to use.

At the tactical level, the collection challenge concerns the information needed to accurately recognize and identify the naval asymmetrical adversary forces, which can be embedded among civilian infrastructure and an innocent population.

After the collection challenge, the next major hurdle is the assessment challenge, which also concerns two levels that aim to build an accurate picture of the opponent and complete the intelligence puzzle.

At the strategic level, the challenge is to understand the asymmetric opponent’s capabilities, their combat systems’ capabilities and performances, and his operational doctrines. Perhaps the most significant challenge is to recognize his training and operating routines. Knowing the opponent’s routines and operational patterns makes it possible to assess when a change occurs and perceive his attention to shift into an attack or different operating pattern.

The tactical level challenge, which relates to identifying fishing boats, fishers, and merchant ships as a suspicious maritime activity, is very complex. The tactical intelligence challenge requires identifying abnormal signs and distinguishing with a high-level of confidence between innocent civilians and vessels versus naval or terrorist activities. The covert force development processes, assimilation among civilians, and camouflage in civilian infrastructure can make it very challenging to assess intelligence and indicate changes in activity and operational patterns.

The final challenge in this context is the assimilation challenge. This challenge involves intelligence officers’ and organizations’ roles in changing perceptions, combat doctrine, and changing force buildup and procurement processes among decision-makers and the commanding officers. Intelligence assimilation among decision-makers is also required to carry out operations and ongoing operational activities during wartime and peacetime. Fighting against asymmetric naval forces, operating from a civilian population, in coordinated multidimensional swarm attacks, using different combat systems, requires different naval combat concepts than those applied in the classical naval battlefields.

Intelligence officers are required to skip over the “walls” of information security and sources-security, and to produce a clear and open dialogue with the operational levels, without exposing sources and incurring risk.

For example, intelligence officers will almost always choose to present threats or the opponent’s operational activity using probability levels. The operational level or decision-makers will classify a threat as “Yes” or “No,” and at its severity level, for example, whether the suspected boat belongs to an innocent citizen or a terrorist.

Intelligence officers’ role is to overcome this cultural gap and present a precise, up-to-date, and reliable intelligence picture that will influence decision-making to make optimum decisions while saving lives, even if they encounter personal resistance and doubts from the operational level.

Conclusion

Since the attack on the Israeli missile boat, further asymmetrical naval forces have developed in the Middle East and Asia, most of them inspired by Iranian naval doctrine, including Hezbollah, Hamas naval units, and the Houthi rebels in Yemen. It should be noted that Iran and China use asymmetric naval forces, which operate alongside traditional navies.

Asymmetric naval forces pose highly complex intelligence challenges to the navies that may need to comfort them, and require different intelligence gathering, research, and assessment techniques. Yet even in the asymmetric context the purpose of naval intelligence will remain the same: to understand rival navy capabilities, intentions, and operations.

Eyal Pinko served in the Israeli Navy for 23 years in operational, technological, and intelligence duties. He served for almost five more years as the head of the division at the prime minister’s office. He holds Israel’s Security Award, Prime Minister’s Decoration of Excellence, DDR&D Decoration of Excellence, and IDF Commander in Chief Decoration of Excellence. Eyal was a senior consultant at the Israeli National Cyber Directorate. He holds a bachelor’s degree with honor in Electronics Engineering and master’s degrees with honor in International Relationships, Management, and Organizational Development. Eyal holds a Ph.D. degree from Bar-Ilan University (Defense and Security Studies).

Featured Image: Palestinian divers from the al-Qassam Brigades, Hamas’ armed wing, take part in a parade marking the 27th anniversary of the Islamist movement’s creation on December 14, 2014 in Gaza City. (Photo via AFP/ Mahmud Hams)