By Mie Augier and Major Sean F. X. Barrett

This is the second part of our conversation series with General Anthony Zinni, USMC (ret.) on leadership, strategy, learning, and the art and science of warfighting. Read Part One here. In this installment, General Zinni shares his experiences with wargames, Desert Crossing and Millennium Challenge 2002 in particular, and discusses how the differing objectives of service chiefs and combatant commanders manifest in wargames. Gen Zinni then touches on the U.S. military’s overreliance on technology and draws parallels from the business world to inform approaches to great power competition.

What are some of the challenges to organizing effective wargames?

Zinni: When I was at Quantico, we started going through a phase where everybody was into board games and tactical decision games, and that sort of thing became really popular—parallel to maneuver warfare development. I came away with several impressions. I think gaming was more valuable at the lower levels, at the tactical level, maybe lower operational level. I think there you can construct the game in a way at the division level or below where nobody is promoting anything, and you can design games to learn specific things and bring out specific points. As you go higher up, I found there was too much in the way of service politics and other things that were injected into the games.

There are a lot of assumptions about capabilities that belie reality or truths and other factors. For example, I found that when playing with the Army after they first introduced the Apache helicopter, you couldn’t shoot down an Apache helicopter. No matter what you did, that was impossible. They were defending the program, and they wanted to build it up.

When I was a two-star, I was in charge of the Marine Corps side in a game we used to do with the Navy every year. The game was more designed to showcase what capabilities we wanted and really focus on things where Navy-Marine Corps cooperation was needed to gain the capabilities, either because of the way they had to be employed or because of the way budgets work. It usually ended up being kind of a swap meet. We had to find compromises because the budget wouldn’t support everybody’s wish list. When we went through the massive Millennium Challenge games with Joint Forces Command, I watched how the games became more designed as proofs of capabilities—preordained proofs of capabilities—rather than—as much as they advertised it—open testing, having a real willingness to fail, and all that.

If somebody talks about a game, I am usually highly suspicious about what the purpose is, who is designing it, and who is sponsoring it. To me, that is critical. The other thing I found in gaming is the intelligence guys always present you with the indestructible, undefeatable enemy. They love to do that. You must overcome that to an extent.

What are some of your experiences that showed the value of wargaming?

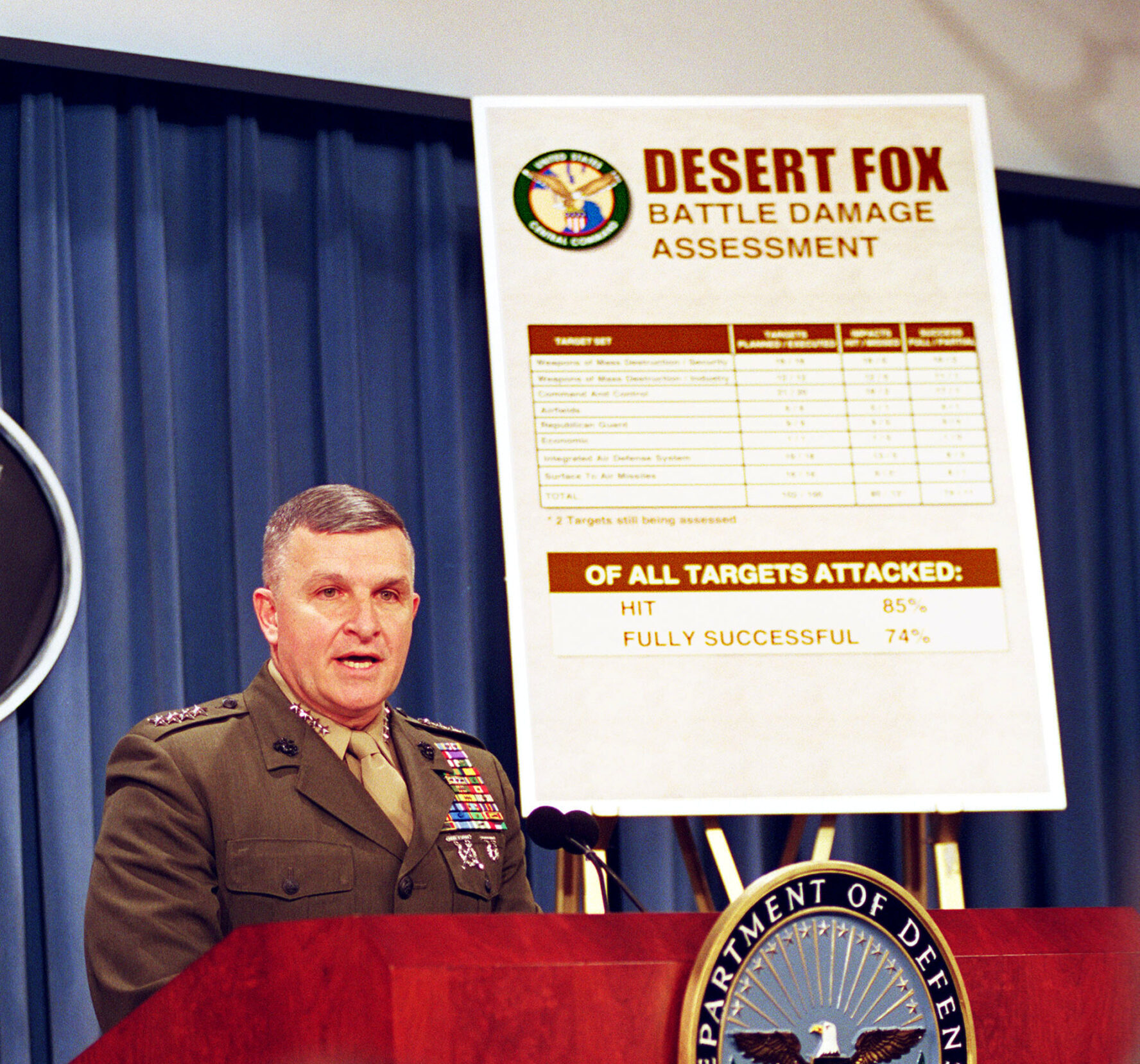

Zinni: When I was Commander-in-Chief at U.S. Central Command, we were on-and-off bombing Iraq when Saddam did not cooperate with the UN inspectors. At that time, if Saddam didn’t cooperate, President Clinton immediately wanted to pull the UN inspector out and hit Saddam. It always worked. Saddam brought the inspectors back in, so President Clinton gave us the okay on anything we wanted to target, basically, you know, make it painful. Since we knew these opportunities arose, we didn’t just want it to be haphazard targeting. We deliberately targeted air defense systems. Although we couldn’t plan on when he didn’t want to let inspectors in or when he’d give them a hard time, we had a systematic way of taking down his air defense systems when these events occurred, and we were very successful. President Clinton OK’d us bombing downtown Baghdad and taking down his intelligence headquarters and a couple of other things. It was called Operation Desert Fox.

Saddam knew when the inspectors left, he was going to get hit. In the past, we always had to bring a few things in before we could launch strikes. One particular time, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs GEN Shelton asked me, “Could you do something so that virtually, as soon as Richard Butler (who was the head of the UN inspection team) is out, you go?” And we did. The battle damage assessment was phenomenal. Four days of strikes. The targets were really large ones. We usually used either the Swiss or the Polish embassy in Baghdad to give us feedback. Well, suddenly—and I’ll get to the gaming piece of this—they started saying, “You guys have to know what you are doing here because this last set of strikes really shook the Iraqi government. The normal hostile rhetoric afterward was gone. They were shocked by the targets you hit, and there are all kinds of rumblings on the street.” We were even getting some feedback that there were some Iraqi generals talking about taking out Saddam if those kinds of strikes continued, and giving feelers to our allies, too.

The next thing that happened, I got calls from both Jordan and Kuwait saying they were getting this feedback, too. Their worry was that if we struck the government to the point that it was overthrown, or hit a target that shut down communications or whatever, they could see major uprisings and then massive amounts of refugees streaming across their borders. I got asked by the national leadership of both countries: What’s your plan if this happened? What’s your plan for massive refugee outflows? What’s your plan for a government that totally collapses, which it could from your airstrikes, and the country becomes a mess? I realized that our war plans were only designed to take out the Republican Guard and take down the military structure. There was nothing in our war plans, or in what we were directed to do, that talked about the post-kinetic period. I thought I could do my job—take out the military—in less than three weeks. But who would be in charge of rebuilding Iraq or creating a new government?

I sent a request up through the chain to the Department of Defense and Department of State asking who had the aftermath plan. I had a feeling it was going to be a total mess. We needed a post-kinetic plan that meshed with our military plan. Well, the answer we got is no one was thinking about this. I asked if we could do a study on what Iraq would look like if the government collapsed, or if we had to go in and take out the military. What kind of Iraq would we find? The State Department, CIA, and all the intelligence organizations agreed to be involved, and my chief of staff said, “Let’s contract a study.” We went to Booz Allen (BA), and the BA people recommended we do a wargame instead of a study because as we discovered things, what we were really after was: what are our options, what should we do? You should put yourself in a position where you have to make those decisions, so you know what kinds of decisions are necessary. Only a game can generate that.

I committed to a couple of weeks up in Washington so we could go through this. We did it, and it is now declassified. It was called Desert Crossing. We went through the game, and I was frankly shocked at what everybody’s consensus was—that when we went into Iraq to take down the Republican Guard, that wouldn’t be very difficult at all. The problem we would have, even with the forces we had in our war plans, which was overwhelming force and which Rumsfeld threw away, was what happened after that. My intention was to get control of everything right away. The one thing I learned in places like Somalia and elsewhere is if you lose momentum, it is hard to get it back.

Unfortunately, the results of the wargame were that this place was going to come apart like a cheap suitcase. I went back to the State Department and DoD and said, “Okay, we looked at this, and this is what we see happening.” And by the way, everything out of that wargame is exactly what happened when we did go in later. This wargame was in 1999, my last year at CENTCOM, and no one was willing to stand up and plan. The State Department wasn’t going to own up to it. They did not want to get involved in the planning. Nobody else at DoD or anybody else wanted to take this on. I told my people that if this were to happen, either because there was an intentional decision to go into Iraq, or because of our airstrikes and everything we were doing, and the country internally imploded, we would be forced to go in, so let’s plan for it.

My chief of staff said, “You know, a lot of this stuff we are looking at is not us. We don’t rebuild governments, and we don’t know how to build economic systems and all that.” I said I didn’t care. We were going to plan and assume we’d have to take it on. I said, if nothing else, we might not be able to understand what had to be done, but we could at least help identify the problems and what we expected might happen. At least we could have an outline of the things we needed to consider because we might be putting together a pickup team to get them done. We began the Desert Crossing planning based on this even though we weren’t tasked with it.

When the decision was made to go into Iraq, this surprised the hell out of me because there was no need to go into Iraq. Saddam was no threat to anybody, nobody was afraid of him, and we had bigger fish to fry in Afghanistan. Then I saw Rumsfeld throw away the war plan. He thought he could do it on the cheap, which really told me that the new plan was going to exacerbate the problem tremendously because you were not going to have control of the people, you were not going to have control of key facilities, you were not going to have control of the borders, and all of this was going to come back to haunt you.

I called down to CENTCOM. I was retired, but I talked to the deputy commander. I told him, “You guys are crazy.” First of all, the war plan that Rumsfeld was talking about involved far too few troops, meaning we’d get overwhelmed, and that place was going to erupt in many different ways, and we’d be unable to control it. And I said, one thing we needed to look at was Desert Crossing because that would give us an idea of what to expect. He said he’d never heard of Desert Crossing. We had worked on that plan up until I retired in October 2000. Whatever was done on that plan at CENTCOM afterward was completely blown off by the leadership there.

You know, when you are retired, you don’t like to go back and poke around your last command. I mean, it is just not done. However, a number of the staff that were still there contacted me and told me about the plans they were being forced to put together, the troop cuts, the assumptions being made—it was just going to be a disaster. And of course, it was.

My point in all of this is that in that Desert Crossing game, we had a specific objective in mind—to learn what was going to happen. Let’s put together the best minds, the best intelligence organizations, and we had every one of them there. They very accurately gave us a picture that we had not put together before that. Unfortunately, it got lost in translation and transition and amidst arrogant people that came into leadership at DoD and elsewhere. Colin Powell understood it, but that’s not who President Bush listened to on this. We ignored everything we learned from that game.

The COCOMs have very specific requirements they are looking at, as opposed to the services that are looking more broadly at future capabilities. How does this impact the effectiveness of the wargames and exercises they both conduct?

Zinni: The gaming with the COCOMs is very different from service-level gaming, which is trying to validate or prove capabilities that the services want and need to get the budget for. At the COCOMs, you are gaming war plans. That is basically what you do. In exercises and in gaming, you usually have specific things you either want to test or learn, and they tend to be things you are testing or want to learn that affect a war plan or a contingency plan, or something along those lines. And of course, having been a former COCOM commander, I’m going to tell you that ours were honest, and the services’ were not.

However, sometimes when you bring allies in, you have to be a bit careful because, first of all, intelligence sharing becomes a problem in some of these things, but you also don’t want to embarrass allies. For us, to play a game and get defeated, we can take it as the result of wanting to learn or test something. For some allies, that is politically unacceptable. They were more into looking good coming out of the game, and that overrides learning. As CENTCOM commander, in exercises and gaming, I worked very hard at trying to get our key allies to embrace more free play. I found that the key was you have to get the top guys onboard with that, because below that, they aren’t going to accept it unless they know they can make mistakes and that will be okay. They may look bad and fail at something, but it is supposed to be a learning event—rather than one where your main concern is about looking bad in front of your boss. So, I think there is maybe more honesty in the gaming with combatant commanders. That is sort of driven by how you are exercising real-world war plans and operations. You can’t polish over or become pollyannish about something that isn’t real, but there are times when you must be careful with that, like I said, with allies and when you have a concern with intelligence sharing.

The other thing is you don’t want to take too much on in a game. I always felt you got more out of the game or exercise if you had a specific handful of things you wanted to learn and focus on, as opposed to trying to eat the big enchilada and do the whole war plan. That gets too unmanageable, and it gets too diffused and diluted. If you look at specific parts of, say, a plan or whatever you are trying to do, and pick five or six things you really want to focus on, the game is much more meaningful.

How were you involved with the Millennium Challenge wargame?

Zinni: I was a senior mentor. Back in those days, Joint Forces Command wrote joint doctrine and conducted joint training and joint wargaming. They brought in retired generals to be senior mentors and to play the red team, as Lieutenant General Paul K. Van Riper, USMC (ret.) classically did with Millennium Challenge, when he exposed all the things we mentioned earlier—trying to be too scripted or prove capabilities, rather than being true and honest with open testing and free play.

They advertised Millennium Challenge as this super, all-time greatest military exercise game. It was going to involve forces from all over the military. This was going to be a proof of concept of the U.S. military writ large. They had a scenario, and they placed this big emphasis on if we failed, that was fine. It was going to be completely free play, and we’d go wherever it took us. Supposedly. Well, when I got there, I asked who was leading the red team. They said Paul Van Riper, and I said, “You guys better have your stuff together because you are going to die.” They kind of blew me off, like this was going to be a piece of cake.

They started the game, and there was a lot of media attention. After the first two or three moves, Van Riper had sunk half of Fifth Fleet and destroyed a corps. They stopped the game because it was now turning into a disaster. They brought everybody in and said they were going to restart the game because some things didn’t go right or whatever. Van Riper didn’t do what they thought or assumed he would do. They thought they had him figured out, had the “enemy” figured out.

They started the game again—same result. Van Riper kicked their butts, and now they stopped again. People were coming down from the Pentagon, and this was becoming a problem. They then said they were going to start for a third time, but this time they told Van Riper what he had to do. He said if they wanted him to go by a script, they had to advertise that it was not free play—that it was scripted. You can’t advertise something as free play when it is really being scripted—that is dishonest. They told him they were not going to do that, but that Van Riper was going to be scripted in many of the things that he could do.

The next thing that happened was a bunch of the majors that were down there revolted and went to the media, and of course Van Riper then became a superstar for every young officer in the military. Malcolm Gladwell even wrote about it. This went all the way up to the Joint Chiefs, and the Joint Chiefs dissed Van Riper and didn’t defend him. Van Riper became the hero for everybody involved in Millennium Challenge below the rank of one-star.

Are we overreliant on technology for solutions? What are some potential pitfalls of this approach?

Zinni: Yes, it is in our nature to become overreliant on technology because we created this dependency on it, and in addition to that, in some ways, we don’t leverage it enough. Every time I get into a discussion with someone about facing a peer-level military threat, it always comes down to the same thing: Well, they’ve got missiles that are going to crush us. The answer is always that we must go after those missiles, we must find them, and shoot them down. What everybody is losing sight of is one of the first things I ask: How does the missile know where you are? Then there’s a fall back: Tell me how they target you. The missile is back there, and you are out here, and they can’t see you. Something is targeting you. Is it a satellite? Is it a recon unit? Instead of wasting all this effort and resources on new technology to kill the missiles, could we blind their missiles? Could we deceive the missile in some way? Maybe the focus of our technology should be on defeating targeting, and maybe the ways we defeat it is to give it a false image, to blind it, to deceive it. To address the threat through better tactics, using what we already have. No one ever talks about that. Everybody just pushes the technology to kill the missile. My point is that it is not just overrelying on technology. Sometimes it is not knowing how to use technology through tactics to build an advantage.

In Millennium Challenge, the blue force was totally dependent on monitoring the red team’s communications, so Van Riper did not use any digital technology. He used motorcycle couriers and all kinds of alternative, simple sources of communication. He did nothing that could be captured or intercepted, so they were totally blind. They put all their eggs—that they would have superior technology to intercept his communications—in one basket. They assumed he would never initiate the fight—that this enemy would be so overwhelmed he would not attack during the build-up phase. Of course, Van Riper immediately attacked. It was a beautiful thing to watch! When we make too many assumptions, it becomes a vulnerability.

The Commandant of the Marine Corps recently published a new doctrinal publication on competition. From your business experience, what are some lessons learned that might be applicable to this new mindset that the service and DoD writ large are adopting? What does it mean to compete with a peer threat below the level of an actual conflict?

Zinni: In the business world, when you look at competition, you look at three things. When you go after a contract or something, you bid on it and put a proposal out there. Your reputation begins with that proposal. For the customers you are dealing with—let’s take the defense industry, and you are dealing with the Defense Department and services you are going to provide—you are going to be known by the quality of those proposals. If you have a series of proposals that have flaws in them, you are going to get a bad reputation and soon become uncompetitive. That’s how you first establish your reputation in a competitive sense.

Let me draw parallels with the military. Basically, what you are doing is you are putting out proposals to allies and potential enemies. In other words, you are framing yourself. This is going to be your reputation because if you can’t live up to it or have a reputation of claiming things that don’t work or whatever, then you begin to lose credibility, and you begin to tempt the enemy to test you.

You also need to realize you can’t compete across the entire spectrum. You need to identify the signature capabilities that really make up the heart and soul of your company and build your reputation around them. In a military sense, these are the things you must be the top in—let’s say missile defense, or nukes, or whatever. There are certain things that are so critical to your essence and what you are doing that you need to focus more on them.

The third thing, which is critically important in the business industry, is you need your best people where you touch your customer or your client. In the business world, I want to make sure I have people out there who have customer intimacy, familiarity, and trust. They are my selling point. People want to come back to your company because of these people. Relating this to the military: Who are your combatant commanders? Who are your senior generals? Who do you put out there as military attachés, or the military people who are negotiating or interacting with allies? If the enemy is in the Middle East, he is looking at the CENTCOM commander, and your customers and allies are looking at that commander, too.

One of the problems the military has is that capabilities are not centrally determined. Every service, every service secretary, and every service chief fights for something, and we don’t have a good way of looking at tradeoffs and risks. What happens is when there’s a budget cut and you need to take risks, it is sort of salami-sliced across the DoD, and no one, particularly at the top, has enough power to say we are going to do this, but not that. This was Eisenhower’s complaint when he talked about the military industrial complex—the military wants everything. They didn’t come to him saying we are going to take risks here, and this is how we see the budget. He just had four services wanting everything. That becomes part of the problem, particularly if you relate that to “signature capabilities.” You must pick which ones are your signature capabilities and are most important for you not to take risks in—and even more importantly, where you are willing to take risks, and what the tradeoffs are.

In business, you measure yourself against what I call a competitive set. For example, say I am on the board of a real estate investment trust that owns 12 hotels. We are basically a small hotel company—a real estate investment trust. We have about a dozen competitors in our peer competition set. You watch that set very carefully. Investors who are going to invest at that level will look at you compared to the others. If you apply that to the military, peer competitor means “the big guys” (Russia and China), but there are capabilities within our military that are not necessarily designed to be about the big fight.

We don’t do so well in the “least likely” conflicts, like when we get caught up in the Iraqs, Afghanistans, Somalias, and Vietnams. We don’t do well in that competitive set. I always say you never fight the war you prepare for. Logically, you should prepare for the war you don’t want to fight, but that means for all the others, you don’t have the perfect capability to engage in them. Some of that is not military related; it is political will, which erodes over time if you are not showing success. I think you saw that in Iraq and in Afghanistan.

General Anthony Zinni served 39 years as a U.S. Marine and retired as Commander–in–Chief, U.S. Central Command, a position he held from August 1997 to September 2000. After retiring, General Zinni served as U.S. special envoy to Israel and the Palestinian Authority (2001-2003) and U.S. special envoy to Qatar (2017-2019). General Zinni has held numerous academic positions, including the Stanley Chair in Ethics at the Virginia Military Institute, the Nimitz Chair at the University of California, Berkeley, the Hofheimer Chair at the Joint Forces Staff College, the Sanford Distinguished Lecturer in Residence at Duke University, and the Harriman Professorship of Government at the Reves Center for International Studies at the College of William and Mary. General Zinni is the author of several books, including Before the First Shots Are Fired, Leading the Charge, The Battle for Peace, and Battle Ready. He has also had a distinguished business career, serving as Chairman of the Board at BAE Systems Inc., a member of the board and later executive vice president at DynCorp International, and President of International Operations for M.I.C. Industries, Inc.

Dr. Mie Augier is Professor in the Graduate School of Defense Management, and Defense Analysis Department, at NPS. She is a founding member of NWSI and is interested in strategy, organizations, leadership, innovation, and how to educate strategic thinkers and learning leaders.

Major Sean F. X. Barrett, PhD is a Marine intelligence officer currently serving as the Operations Officer for 1st Radio Battalion.

Featured Image: U.S. Marines assess a terrain map during a simulated amphibious assault of exercise Talisman Sabre 19 in Bowen, Australia, July 22, 2019. (U.S. Marine Corps/Lance Cpl. Tanner D. Lambert)