China’s Defense & Foreign Policy Topic Week

By Pawel Behrendt

The opening of the Chinese military base in Djibouti on August 1st is a landmark event; China finally has its first overseas military outpost. The parallel of similar activities undertaken by the Germans in China at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries is noteworthy for offering lessons on the relationship between force structure, maritime strategy, and overseas basing.

Djibouti is strategically located on the African shore of the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, which separates the Indian Ocean from the Red Sea, making it proximate to one of the most important sea routes linking China with Europe. For years this small country has hosted military bases of foreign powers such as France, the United States, and Japan. Over the past decade, the existing facilities have offered crucial support to forces fighting Somali pirates. China takes part in this mission, too. However, with the development of the Belt and Road Initiative Djibouti has started to play a vital role on the Maritime Silk Road of the 21st century. Since about the year 2000 China has striven to build and secure its own presence in the Indian Ocean basin. After successfully establishing footholds in Pakistan (Gwadar) and Sri Lanka (Hambantota), the next logical step of the Belt and Road Initiative was at the doorstep of the Suez Canal – Djibouti.

Nevertheless, the news of the intention to build a Chinese base came as a surprise in mid-2015. Negotiations proceeded quickly, an agreement was signed in January 2016. The $600 million project was launched the following year. Works on the main body of the facility have already finished, but other parts are still under construction. In reality nobody knows how complex the base is going to be. The first convoy carrying troops to Djibouti departed on July 12 from the port city of Zhanjiang. The base was officially opened on August 1, a very symbolic date – the 90th anniversary of PLA. Beijing is reluctant to use the term ‘military base’ and instead refers to it as a “support facility” that will provide logistical support to forces taking part in UN missions in Africa and the anti-pirate operation. The existing agreement allows the PRC to station 6,000-10,000 troops (sources vary) until 2026. An additional bonus to Djibouti is a $14 billion infrastructure project.

The meaning of the first Chinese overseas base, however, goes far beyond the Silk Road and commerce. China has gained the ability, however limited it may be, to project power in the still unstable Middle East while also strengthening its position against India. Additionally, there are issues of prestige: the PRC has joined the small group of powers that maintain overseas bases. This is very important for a nation that is increasingly self-confident and aims to become a leading power. What most likely accelerated the decision to acquire overseas bases was the Arab Spring of 2011. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) was unable to evacuate Chinese citizens from revolution-torn Yemen and Libya and was forced to ask the U.S. and France for help. Both the Chinese leadership and many ordinary citizens regarded this as humiliation. Thus the buildup of the PLAN initiated in the early 21st century gained wider support and was indicated as one of the key objectives of the modernization and reorganization of the Chinese military. What’s more, a strong navy is seen as a mark of the status of a great power and as a crucial factor in securing crucial sea lines of communication (SLOCs). It must be pointed out that around 80 percent of Chinese oil imports come via the Strait of Malacca. The numbers are even more impressive when it comes to trade: despite extensive land infrastructure programs, around 99 percent of trade exchange with Europe is seaborne.

Historical Parallels with Germany’s Asian Colonialism

It is worth asking whether China really needs an overseas base and what are the chances of sustaining it in the event of a full-scale conflict. Very interesting conclusions come from the history of German colonial presence in Asia. The topic of obtaining an overseas base in Asia was brought up for the first time during the German Revolutions of 1848/49. The colonial idea found many advocates at the National Assembly in Frankfurt. This was connected with the brutal opening of the states of Asia to the world. The Far East was at that time a “Promised Land” where one could sell any amount of cheap European products and in exchange buy valuable tea, silk, and porcelain. However, for exactly half a century since the issue had been raised, Germany had done nothing to get an overseas base, even though the topic kept coming back like a boomerang. The reason was that the “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck saw core German interests in Europe and was strongly against any “colonial adventures” that could antagonize Great Britain.

The situation changed in the late 19th century. Germany was an emerging power striving for a “place under the sun.” The young emperor Wilhelm II was determined to turn Germany into a global power and initiated the “Weltpolitik” (world politics), challenging Great Britain and France. The Kaiser was also influenced by the theories of Alfred Thayer Mahan. He had several copies of The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783, and the margins of one of them were densely covered with notes and commentaries. Thus Wilhelm II had a scientific leverage for his passions: a strong navy and colonies. He found a big ally in Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. This politically talented officer was a supporter of the ideas of a naval buildup and obtaining an overseas base in China. What’s more, he was able to convince the Reichstag (parliament) to allocate huge sums of money for this purpose.

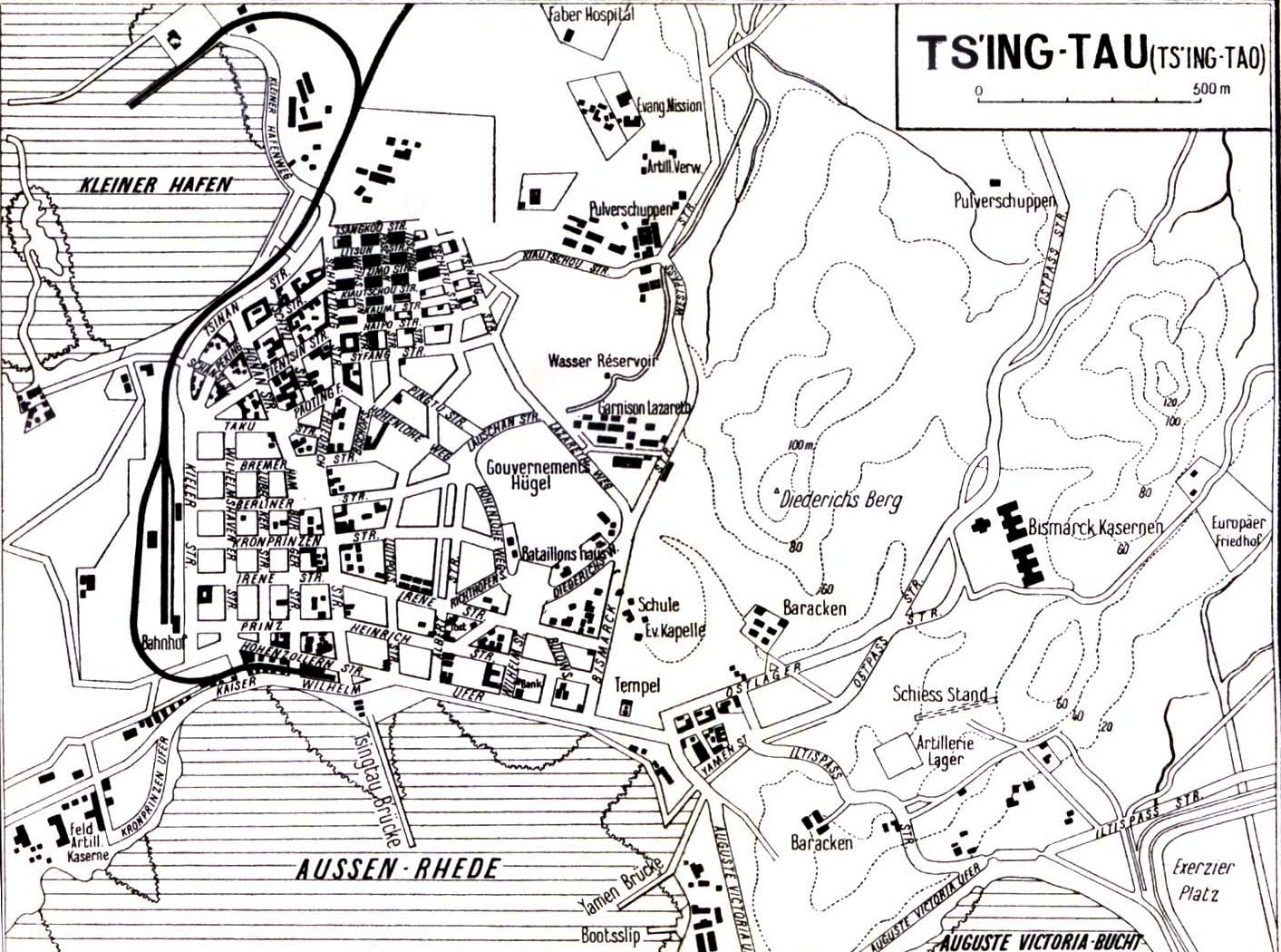

The dream of a foothold in the Far East came true in 1898. That is when China and Germany signed a treaty which leased the small fishing village of Qingdao (then Tsingtau or Tsingtao) to the Germans for 99 years. Within 16 years Qingdao evolved into one of the biggest ports of China. There was also a fierce discussion what to do with the overseas base. In official documents the term “Gibraltar of the Far East” began to appear. The German Admiralty wanted to create a mighty fortress and naval base. However, Admiral Tirpitz had different ideas. He was well aware that a globally meaningful Navy had yet to be built, and in the event of war the chances of coming to the rescue of the fortress were negligible. He thought holding Qingdao rested on good relations with Japan. Vice Admiral Friedrich von Ingenhol agreed; he bluntly said that in a full-scale war the base would be useless. Thus Tirpitz decided to create an equivalent of Hong Kong, an important trade port and a center promoting German culture. In this field the Germans managed to achieve quite a lot of success, creating—among other things—one of the first resorts in Asia.

The admirals’ predictions came true, Japan decided that fighting alongside the Entente was more beneficial than remaining neutral or siding with Germany. So Qingdao played virtually no role in World War I and fell in November 1914 after a two month siege by joint Japanese and British forces. Similarly, the huge fleet of battleships built with a tremendous effort and use of resources, a fleet second only to the Royal Navy, stayed in its bases for most of the war. Tirpitz himself said, after he learned about the outbreak of war, that the Hochseeflotte (High Seas Fleet) would be useless. The main reason was geography. To rule the waves (and support distant basing) any navy needs unobstructed access to the ocean. Meanwhile, the North Sea and thus the main ports of Germany are separated from the Atlantic by the British Isles and Shetland Islands. This allowed the British to establish the effective distant blockade of Germany in 1914 and—save for the battle of Jutland (in German: Skagerrakschlacht)—avoid a major confrontation. The German Navy failed to find a counter for this strategy and as early as 1915 the naval war was ceded to the light forces and submarines. Neither the powerful shipbuilding industry nor the strong merchant fleet, nor the rich maritime traditions of northern Germany, were able to overcome the shortcomings of geography. The same scenario was repeated during World War II even despite the occupation of ports in France and Norway. Germany had remained a land power, and Britain, by virtue of being the dominant sea power, could maintain a network of meaningful military infrastructure across the globe.

China’s Present Challenge and Geographical Constraints

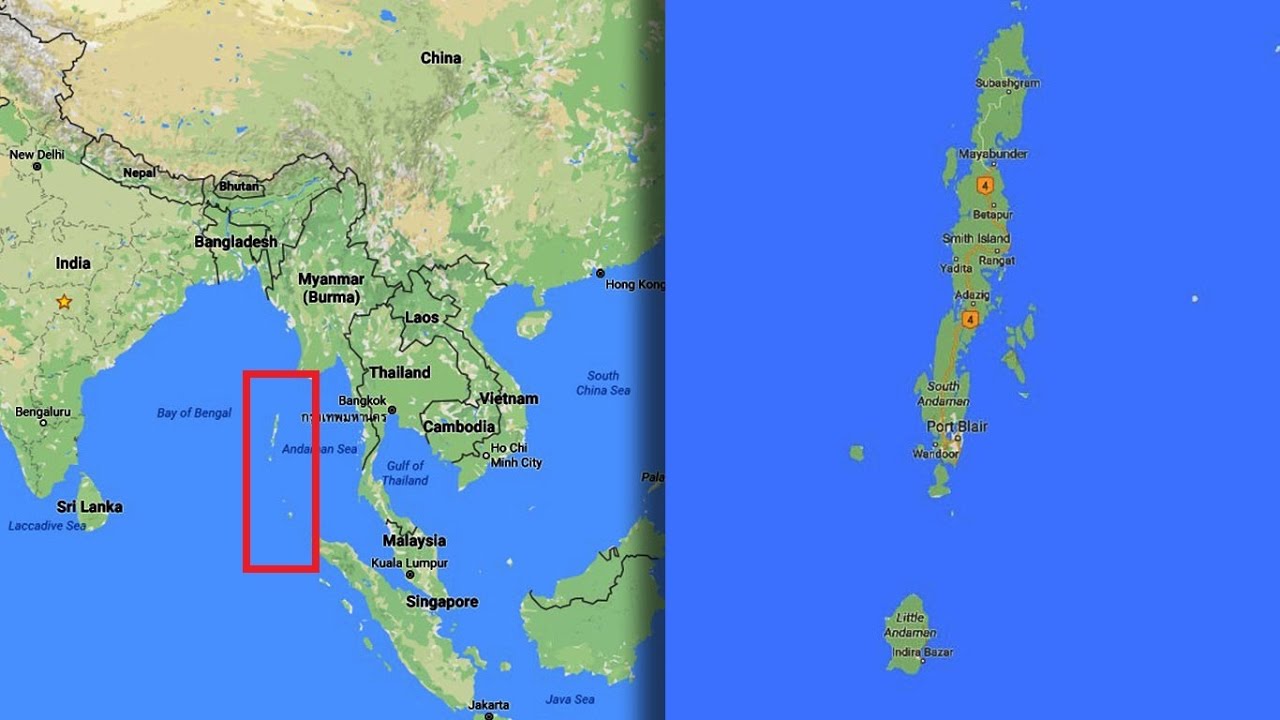

Despite being located on the opposite end of Eurasia, China faces the same problem as Germany due to the crucial role of geography separating the mainland from the Pacific Ocean. The first island chain comprises the Kuril Islands, the Japanese Archipelago, the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, the Philippines, and the western shore of Borneo. The area thus inscribed includes waters directly adjacent to the Chinese coast. Despite the enormous resources invested in the fleet, the PLAN is only now starting to operate outside this border. More southwards China is separated from the Indian Ocean by the Malay Peninsula and the islands of Indonesia. There are also three “bottlenecks” determining maritime traffic between East Asia and Indian Ocean and Europe: the Straits of Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok.

Most of these strategic points on the map are controlled by the United States or its allies. For this reason, China has decided to create A2/AD (anti access / area deny) zones in the East and South China Sea that are to limit the space for adversary maneuver. Moreover, an intensive naval buildup is supposed to make any confrontation too risky by introducing a capability to project power beyond A2/AD zones adjacent to the mainland. In numbers the PLAN is now second only to the U.S. Navy. This resembles similar actions undertaken by Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. The U.S. response is also considering surprisingly similar to the countermeasures used by the British. Scenarios of military exercises conducted in the western Pacific by the United States and its allies do not imply a strike against the Chinese Navy and coast per se, but rather impose a distant naval blockade based on the first island chain.

There are also differences. Tirpitz was an advocate of the fleet-in-being doctrine, wherein the fleet by its existence alone puts pressure on the enemy. Such a theory resulted in building battleships which were not useless but rather not used. The Chinese leadership, among whom Mahan’s theories are gaining popularity like they once did in the German Empire, have learned this lesson. The buildup of the PLAN, besides including impressive programs like aircraft carriers and SSBNs, concentrates on SSKs, SSNs, and surface combatant escorts. The latter are related to the pursuit of strategic security on the maritime routes leading to and from China. Chinese admirals also do not claim to be interested in the fleet-in-being concept. The naval development plan has been described as being divided into stages corresponding to obtaining the ability to conduct operations beyond the subsequent island chains. Currently the stage of going beyond the “first chain” is underway.

The question is whether in the case of a hypothetical war against the U.S. and its allies the PLAN would be able to go beyond the safe haven of A2/AD zones and break through the blockade. Such an operation is feasible, but it would involve significant losses. In addition, the blockade is rarely carried out by the main force. Thus after the “defenders” break out into the open the fresh main force of “attackers” is already waiting for them.

The base in Djibouti is very unlikely to provide any sufficient relief. This is the case not only in the event of a confrontation with the United States, but also a confrontation with India whose prime location would allow it to freshly contest the PLAN if were to succeed in breaking through Asia’s maritime chokepoints.

Conclusion

China is geographically and historically a land power. As has been the case with Germany and Russia, a blue water navy can be an expensive sign of prestige and great power status rather than a real weapon of war. Power projection for a high seas fleet in a benign, peacetime environment is a different matter entirely. Germany’s historical experience with maintaining distant naval infrastructure reveals that such basing is often irrelevant in full-scale war and virtually impossible to sustain or defend against assault. China’s navy will need to grow significant capacity and capability if China wishes to continue establishing distant military bases for the purpose of projecting power while hoping to retain them in conflict. Alternatively, China could moderate its overseas ambitions by accepting that such bases are indefensible and whose loss should be affordable so long as China’s naval power projection can be checked by potential adversaries in both the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Pawel Behrendt is a Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Political Science of the University of Vienna, an expert at the Poland-Asia Research Center, and Deputy Chief Editor of Konflikty.

Featured Image: Chinese troops stage a live-fire drill in Djibouti. (Handout)