By Ryan C. Walker

On June 14, 1952, President Harry S. Truman visited the small town of Groton, CT, to commission the USS Nautilus (SSN-571), the first nuclear submarine. Truman, noting the pride present in the community gathered before him, began his speech with a joking comparison to his hometown of Independence, Missouri:

“I am very glad to be here today in Groton, Connecticut. You see, I got the right town this time. Somebody told me last week that this ceremony was going to be held in New London, over on the other side of the river. I referred to it in the speech I made Saturday out in Missouri. Very shortly thereafter I was set right in no uncertain terms. I am glad to see the people of Groton are proud of their hometown. I know how they feel. I sometimes get pretty tired of Kansas City taking all the credit for things that happen in Independence, Missouri. I can understand why the people of Groton should be proud of what is happening here today.”1

The residents of Groton were proud not just from the Nautilus, but for supporting both the Naval Submarine Base New London (SUBASE NLON) and General Dynamics Electric Boat Shipyard (EB). The people living within and commuting to Groton were responsible for building and maintaining a sizeable portion of the American submarine fleet, both past and present. Groton evolved from a sleepy community of 5,600 persons with few businesses, a defunct naval base, and underutilized shipbuilding infrastructure at the beginning of the twentieth century into the self-proclaimed “Submarine Capital of the World.”2 In 2020, at least 64.8 percent of the total workforce is directly associated with the submarine community, 10,350 persons worked at SUBASE NLON, and 8,092 work at GDEB, lending credence to this continued claim.3 Groton is, as described by local historians, “first and foremost, a maritime community.”4

Despite these impressive numbers, significant maritime workforce challenges have emerged. EB President Kevin Graney has embarked upon an aggressive hiring campaign both to fight attrition and support the boom in submarine construction, including by planning on hiring 3,000 more workers after already hiring 2,500 in 2021.5 Why so many? The issues stem primarily from a slowdown in naval activity in the region from 1989-2017 as submarines were decommissioned or moved away from the East Coast and submarine construction slowed. While 8,092 workers seem an impressive figure, 15,000 were employed previously at the EB shipyard in Groton in 1990.6 It is unlikely those local or stationed in the area saw EB or SUBASE NLON’s future as promising in the near or distant future. EB retained the workforce it had, while many of the younger, more junior employees were laid off or sought greener pastures.

There are two sets of issues, short-term and long-term, that EB and many other shipyards ramping up production face. The long-term issues are evolutionary in nature since it takes generations of investment and multiple avenues of funding to develop naval capital towns (NCTs) from scratch. These NCTs provide a critical foundation for naval industry to grow and flourish, making their development a naval priority. An upcoming edited chapter by the author describes this process and offers insights into developing NCTs, which can ensure the United States retains the naval industrial base it currently has and effectively support these communities.7 Groton’s development deserves closer consideration and sets the stage for two potential issues and recommendations for improving NCTs: finding recently separated or retired veterans by revamping rating-to job-conversions and changing perceptions of shipyard work environments and labor forces.

Groton from 1868-1940

The foundations of Groton becoming an NCT lay in EB and SUBASE NLON’s concurrent development through 1868-1940. While SUBASE NLON finds its origins in the predecessor Thames Naval Yard, alternatively known at the New London Navy Yard, it remained stagnant and underutilized throughout much of its life. Questions of purpose and cost would define the New London Navy Yard’s existence, and reasonably so. It was not being used for its incipient recommended purposes— the construction of naval vessels.8 Some ships were put “in ordinary,” but few active ships were in the region.9 One proposition for greater use came from a committee in 1883, who suggested the site was only suitable for building a “naval asylum.” This was met with immediate resistance, with the local newspaper The Day proclaiming in a front-page headline, “Thames Yard Must Go!”10 As can be seen in these early interactions, the federal government was only one interested party among many in the nineteenth century, and was often overridden by state and local interests.11

The Naval Yard was employed for two purposes in the first decade of the twentieth century – as a coal facility in 1900 and Marine Corps officer training station in 1907.12 The Marine Corps school moved to League Island in 1910 and the coaling station appeared to be underutilized, leaving an almost completely abandoned naval base.13 This did not change until EB determined that the current construction facilities in Quincy were insufficient in 1910. The company sent engineer Frank Cable to scout new locations to produce diesel engines. Upon his recommendation, the company selected Groton as the site for future expansion of the New London Ship and Engine Company (NELSECO), purchasing (initially leasing) the abandoned infrastructure from the Electric Shipbuilding Company. His rationale seems to be primarily business driven, since much of the initial infrastructure was already there, waiting for purpose.14 Furthermore, Groton was a shipbuilding town lacking a major employer, the harbor was dredged, the state paid for much of the new roads, railways accessing major cities such as New York and Boston were available, water and transportation costs were low, and it was likely cheaper than using developed facilities in New Jersey or New York.15

The forgotten Thames Naval Yard was likely not a consideration initially, but a promising 1915 visit by President Wilson’s Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, signaled the beginning of change. Daniels’ administration found an issue with how the U.S. Navy had managed its submarines and submarine sailors at the beginning of his tenure and his vision transformed the Thames Navy Yard into the naval base that it is known as today. At the time Sailors were housed in motherships that were manning intensive and expensive, so land bases were explored. Proximity to NELSECO and Lake Torpedo Boat were cited as reasons for the expansion, as both would create a feedback loop of feeding off the other’s success.16 The 1920s were a difficult decade for private yards. But by 1930, critical practices and interconnections had become firmly embedded between government and the local community, which typically characterizes stable defense industry sectors.17 Groton became a NCT in this period, one of the few that has been preserved relatively intact.

Naval Labor Transitions to Maritime Shipyard Labor

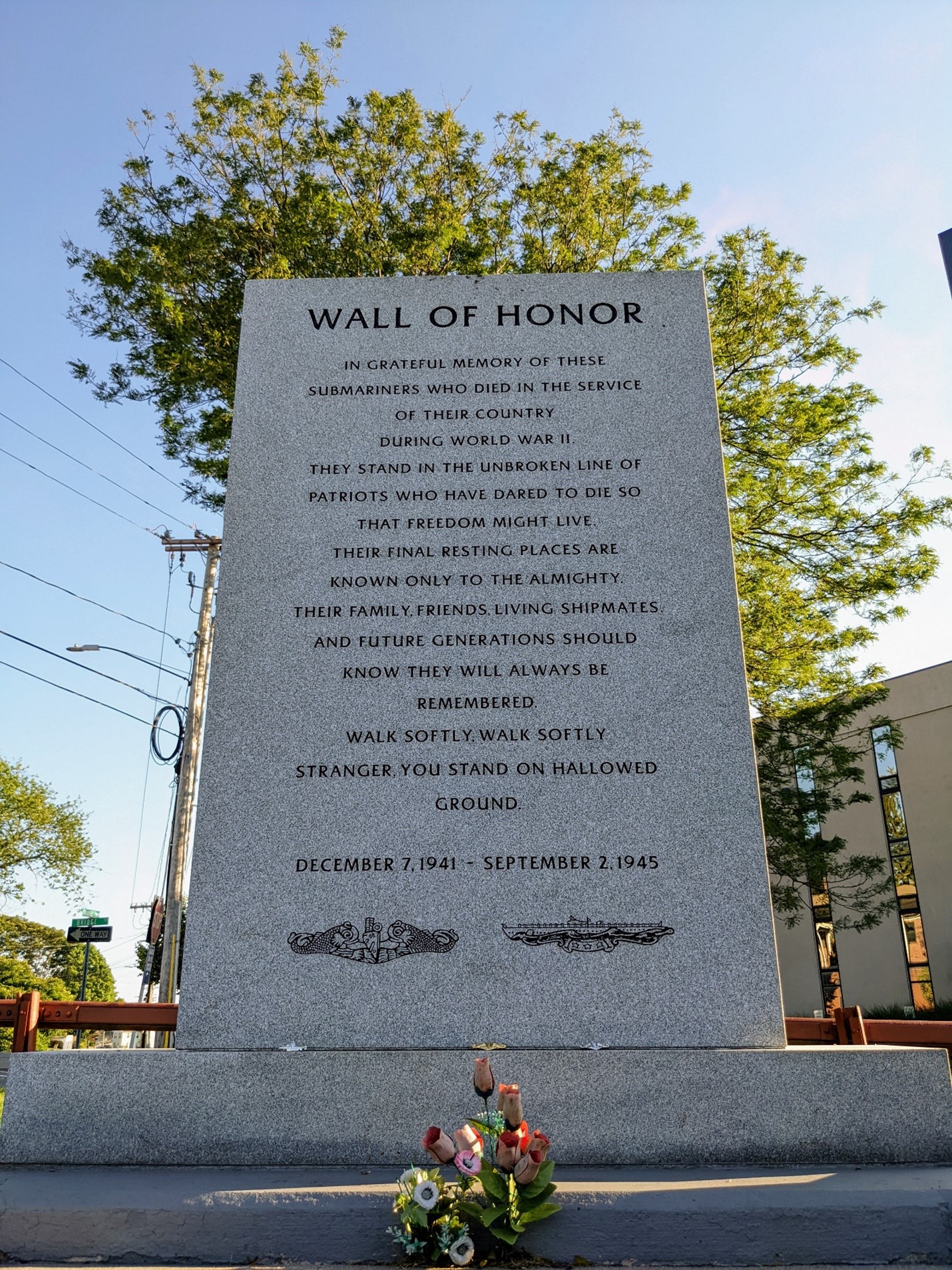

The bonds between the two major employers have become a major part of the identity of Groton as evidenced by the Submarine Force Library and Museum (which also houses the permanently moored USS Nautilus), SUBVETS WWII National Memorial East, and numerous streets and neighborhoods named after submarines. For many submariners, Groton became a home at some point of their careers, and many continue to offer their service in employment developing technology, building submarines or working on base, often drawing from competencies developed from submarine service. This community is the product of a century of commitment and cultivation, developing naval infrastructure, and promoting cross-state migration drawn by the allure of well-paying jobs in the region. Eastern Connecticut has proven uniquely suited to submarine construction because of the long-term investment in the region by all layers of private, public, labor, and military interests and its connection to other NCTs.

Efforts to attract sailors who are recently separated or retired, particularly from the submarine community, should be actively pursued and redoubled. The major hurdles are convincing sailors to not return to their hometown or state and rating-to-job skill training. The former issue is a difficult sell, there are many who are dead set on leaving Connecticut. Yet a qualified enlisted submariner who has completed more than five years of experience is an incredibly versatile person worth pursuing. Their daily duties included not only their rate, but also armed security watchstanding, quality assurance, damage control, supervisory roles, voluntary positions, and more. The skillsets are extensive. These individuals are among the most precious resource to maritime workforces in Groton, yet many leave the areas they served in for a variety of reasons. Finding a place for them, ideally that utilizes their acumen, is key to unlocking the full potential of the bonds between the shipyard, the naval base, and the local community. A submariner has learned quite a bit in their time, learning a trade in the right environment is not out of the question.

Issues with Perception: Who wants to work in a yard?

Part of the reason junior sailors are so important is the relatively insular nature of maritime industry. It is a relatively unknown niche industry that only directly or indirectly employs 393,390 people in the United States, of which 83.1 percent of the directly employed are concentrated in ten states.18 Of these ten states, the highest per capita of ship construction and repair workers belongs to Maine, at only 1.6 percent of the total employment, with Connecticut at 1.2 percent, meaning even in these states there is a high likelihood some may have never considered employment in shipyards.19 Further complicating this are some stigmas associated with shipyard work and workers, the so-called “shipyard bubbas.”

Part of these negative perceptions stems from some societal attitudes that do not effectively value “blue-collar” work or more accurately, “skilled tradesworkers.”20 Dispelling the negative perception of the bubba is necessary moving forward to attract labor. Asking why this perception problem exists, and identifying the root cause, will be paramount to resolving this issue. The answer may come down to management and administration practices. Are leaders willing to adapt and rebrand to attract a younger workforce?

Conclusion

The process to build an NCT is incredibly difficult and requires decades of patience. The main issue for Groton has been funding. The end of the Cold War made a downturn in defense spending inevitable, with significant impacts on the submarine shipbuilding industry and the communities that support the industry. Reversing declining trends in labor over the past three decades will be an uphill battle for naval capital towns like Groton. Rebuilding the feedback loop of success between the EB and SUBASE NLON is necessary to translate retiring naval labor into local maritime labor, all while fighting negative perceptions associated with shipyard work. Expanding work outside of current NCTs may not be feasible in the short term and may be difficult to maintain in the long term. It is much better to focus on the established NCTs, rebuild connections between industry and the Navy, and improve labor management and administration practices.

Ryan C. Walker served in the USN from 2014-2019, as an enlisted Fire Control Technician aboard the USS Springfield(SSN-761). Honorably discharged in December of 2019; he graduated Summa Cum Laude from Southern New Hampshire University with a BA in History. He is currently a MA Candidate at the University of Portsmouth, where he studies Naval History and hopes to pursue further studies after graduation. His current research focus is on early submarine culture (1900-1940), Naval-Capital Towns in the U.S., and British private men-of-war in the North Atlantic. The research for this article came from his upcoming chapter in Seapower By Other Means, (ed. J. Overton), where he explores the process of building Groton CT as a Naval Capital town from 1868-1940. He currently resides in lovely Groton, CT.

Endnotes

1. Harry S. Truman, Address in Groton, Conn., at the Keel Laying of the first Atomic Energy Submarine. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/230973

2. Mary E. Denison. “Historic Heights, or the Borough of Groton.” In Historic Groton: Comprising Historic and Descriptive Sketches Pertaining to Groton Heights, Center Groton, Poquonnoc Bridge, Noank, Mystic and Old Mystic, Connecticut, ed. Charles Burgess. (Moosup, CT: Charles F. Burgess), 1909. 18; State of Connecticut. “Population of Connecticut Towns 1900-1960.” Accessed December 27, 2021. https://portal.ct.gov/SOTS/Register-Manual/Section-VII/Population-1900-1960

3. Town of Groton Finance Department. Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the Town of Groton: Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020. (Town of Groton: Finance Department, 2020). 140. This is a minimum and does not include other significant defense employers in the Groton and the surrounding areas such as Progeny, SEACORP LLC, and Sonalysts to name a few.

4. Carol W. Kimball, James L. Streeter, & Marilyn J. Comrie, Images of America: Groton Revisited, (Portsmouth: Arcadia, 2007). 7

5. Brian Hallenbeck, “Electric Boat president can’t stress it enough: ‘We’re hiring!’” The Day,

6. Robert Weisman, “Layoffs at EB Were Expected, but Still Painful,” Hartford Courant, April 14, 1992, Hartford, CT, https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1992-04-14-0000203265-story.html

7. Ryan C. Walker, “The Development of Groton as a Naval Capital Town: 1868-1940,” in Seapower by Other Means: Naval Contributions to National Objectives Beyond Sea Control and Power Projection, ed. J Overton, ISPK Seapower Series: Kiel, 2023). Upcoming publication.

8. New London Navy Yard Committee. Review of the Minority Report on the Navy Yard Question. (New London: Starr and Farnham Printers, 1864). 35-36

9. Brian Hallenbeck, “Electric Boat president can’t stress it enough: ‘We’re hiring!’” The Day, January 20, 2022, accessed October 3, 2022, https://www.theday.com/local-news/20220121/electric-boat-president-cant-stress-it-enough-were-hiring/.

10. “Thames Yard Must Go!” The Day, No. 772, New London, CT, December 31, 1883. In Google News Archive: The Day, Alphabet Inc. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=SrsqWtBqNIQC

11. Often forgotten was how weak Federal power was until the Great Depression, while the State preoccupied itself creating a welcoming environment for business. Local political power played a major role, alongside private and business interests in much of the United States.

12. U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Hearings Before the Committee on Naval Affairs of the House of Representatives: On Estimates Submitted by the Secretary of the Navy 1906-1907. (Washington D.C: Government Printing Office, 1907). 215

13. David J. Bishop Images of America: Naval Submarine Base New London. (Portsmouth: Arcadia, 2006), 5-18. Bishop has picture of ships at the pier but gives the decline of coal as a maritime fuel as the reason. Coal was still a major part of the USN, so this reason does not capture the full scope of possibilities.

14. Frank Cable. “The Story of Our Plant,” 3-4 The Association Mirror, (May 1935). Submarine Archives, Electric Boat Collection, Submarine Force Library and Museum, Groton, CT. 2-3

15. Benjamin Tinkham Marshall, ed. A Modern History of New London County, Connecticut: Vol. 1, (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1922), 227, 237.

16. Hearing Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations United States Senate, HR 5949, day two, Sixty-Fifth Congress, 1sr sess, September 20, 1917. 88

17. Gary E. Weir, Forged in War: The Naval- Industrial Complex and American Submarine Construction, (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center Department of the Navy, 1993).

18. Maritime Administration (MARAD), The Economic Importance of the U.S. Private Shipbuilding and Repairing Industry, Report, March 30, 2021. https://www.maritime.dot.gov/sites/marad.dot.gov/files/2021-06/Economic%20Contributions%20of%20U.S.%20Shipbuilding%20and%20Repairing%20Industry.pdf 1, 8

19. MARAD, U.S. Private Shipbuilding and Repairing Industry, 20

20. Dana Wilkie, “The Blue-Collar Drought: Why jobs that were once the backbone of the U.S. economy have grown increasingly hard to fill.” SHRM, February 2, 2019, https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/all-things-work/pages/the-blue-collar-drought.aspx

Featured Image: Snow covers the hull of the fast attack submarine USS Virginia (SSN 774) as it sits moored to the pier at Naval Submarine Base New London in Groton, Conn., on Feb. 2, 2007. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)