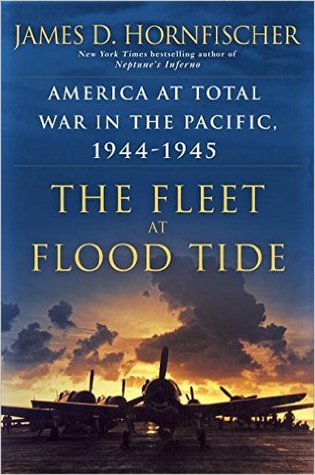

CIMSEC was saddened to learn that renowned naval historian James Hornfischer passed away on June 2, 2021. He was 55.

To celebrate his memory, CIMSEC is reposting this interview we published on his latest book, The Fleet at Flood Tide.

By Christopher Nelson

A passionate naval historian, Jim Hornfischer finds time in the early morning hours and the weekends to write. It was an “elaborate moonlighting gig” he says, that led to his latest book, The Fleet at Flood Tide: America at Total War in the Pacific, 1944-1945.

The Fleet at Flood Tide takes us back to World War II in the Pacific. This time Hornfischer focuses on the air, land, and sea battles that were some of the deadliest in the latter part of the war: Saipan, The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, Tinian, Guam, the strategic bombing campaign, and the eventual use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

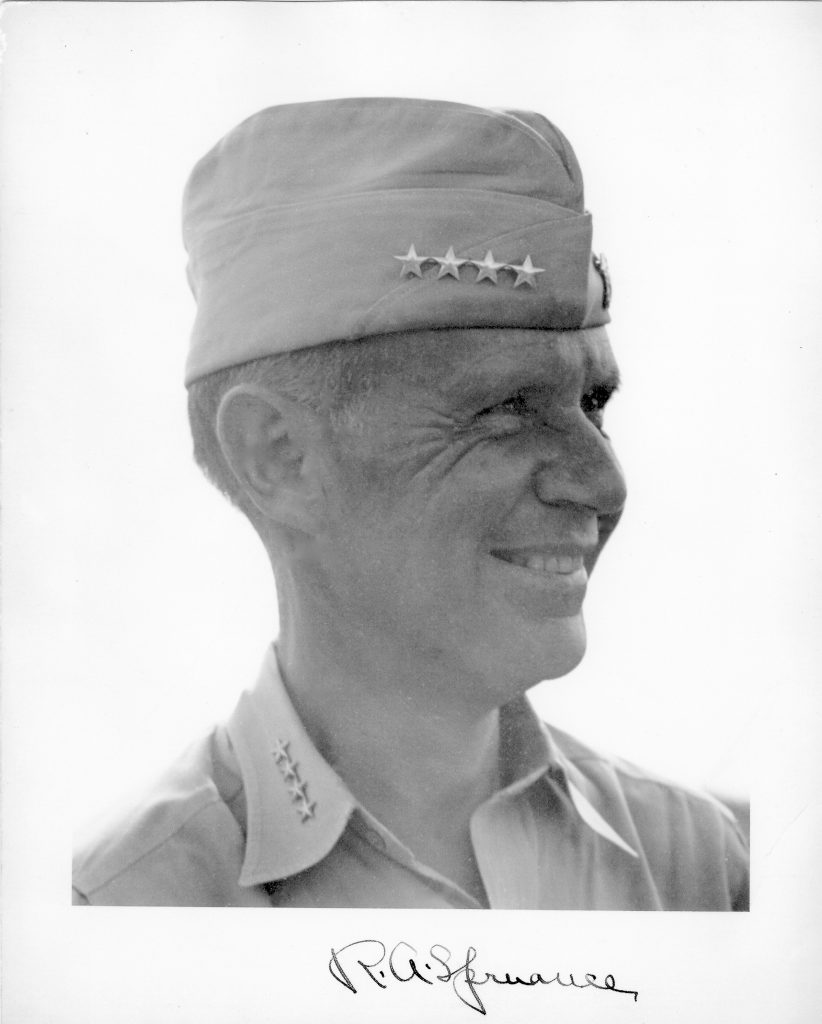

The battles Hornfischer describe share center stage with some of the most impressive leaders the U.S. placed in the Pacific: Admiral Raymond Spruance, Admiral Kelly Turner, Admiral Marc Mitscher, General Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, and Colonel Paul Tibbets. It is quite a cast of characters.

Hornfischer, to his credit, is able to keep this massive mosaic together – the numerous battles and personalities – without getting lost in historical details. His writing style, like other popular historians – David McCullough, Max Hastings, and Ian Toll immediately come to mind – is cinematic, yet not superficial. Or as he told me what he strives for when writing: “I then dive into the fitful process of making this rough assemblage readable and smooth, envisioning multiple readers, from expert navalists to my dear mother, with every sentence I type.”

The Fleet at Flood Tide is his fifth book, following the 2011 release of Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Gudalcanal. Hornfischer — whose day job is president of Hornfischer Literary Management — also found time to write The Ship of Ghosts (2006), The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors (2004; which won the Samuel Eliot Morison Award), and Service: A Navy SEAL at War, with Marcus Luttrell (2012). Of note, Neptune’s Inferno and The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors have been on the Chief of Naval Operation’s reading list for consecutive years.

I recently had the opportunity to correspond with Jim Hornfischer about his new book. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

How did the book come about? Was it a logical extension of your previous book, Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal?

All these years on, the challenge in World War II history is to find books that need writing, stories that need telling with fresh levels of detail, or in an entirely new frame. After Neptune’s Inferno, I was looking for a project that offered expansive territory in terms of geography, people and operational terrain, fresh, ambitious themes, and massive amounts of combat action that was hugely consequential. When I realized that no single volume had yet taken on the entirety of the Marianas campaign and followed that coherently to the end and what it led to, I had something. I wrote a proposal for a campaign history of Operation Forager, encompassing all its diverse operations on air, land and sea, as well as the singular, war-ending purpose to which that victory was put. The original title given to my publisher was Crescendo: The Story of the Marianas Campaign, the Great Pacific Air, Land and Sea Victory that Finished Imperial Japan. In the first paragraph of that proposal, I wrote, “No nation had ever attempted a military expedition more ambitious than Operation Forager, and none had greater consequence.” And that conceit held up well through four years of work. Everything I learned about the Marianas as the strategic fulcrum of the theater fleshed out this interpretation in spades.

As you said, in the book you focus on the Marianas Campaign, and there are some key personalities during the 1944-45 campaign. Namely, Raymond Spruance, Kelly Turner, and Paul Tibbets are front and center in your book. When scoping this book out, how did you decide to focus on these men?

As commander of the Fifth Fleet, Raymond Spruance took the Marianas and won the greatest carrier battle in history in their defense along the way. Spruance, to me, stands as the finest operational naval commander this nation ever produced. After all the ink spilled on Halsey and the paucity of literature on Spruance, it was, I thought, time to give him his due. Kelly Turner, Spruance’s amphibious commander, has always fascinated me. After his controversial tour as a war plans and intelligence guy in Washington in the run-up to Pearl Harbor, and then in the early days of Guadalcanal, surviving a dawning disaster (and did I mention he was an alcoholic), it’s incredible that Turner retained Spruance’s confidence. Yet he emerged as the leading practitioner of what CNO Ernest J. King called “the outstanding development of the war”: amphibious warfare. He has been poorly credited in history and deserved a close focus for his innovations, which included among other things an emphasis on “heavy power”—the ability to transport multiple divisions and their fire support and sustenance over thousands of miles of ocean—as well as the first large-scale employment of the unit that gave us the Navy SEALs.

As for Paul Tibbets, he and his top-secret B-29 group were the reason for the season, so to speak, the strategic purpose behind all the trouble that Spruance, Turner, and the rest endured in taking the Central Pacific. Without Army strategic air power, the Navy might never have persuaded the Joint Chiefs to go into the Marianas in 1944. And without Paul Tibbets and his high performance under strenuous time pressure, the war lasts well into 1946. Did you know that it was his near court-martial in North Africa in 1942 that got him sent to the Pacific in the first place?

Early in the book you say that naval strategy was driven more by how fast the navy was building ships and not by battle experience. How so?

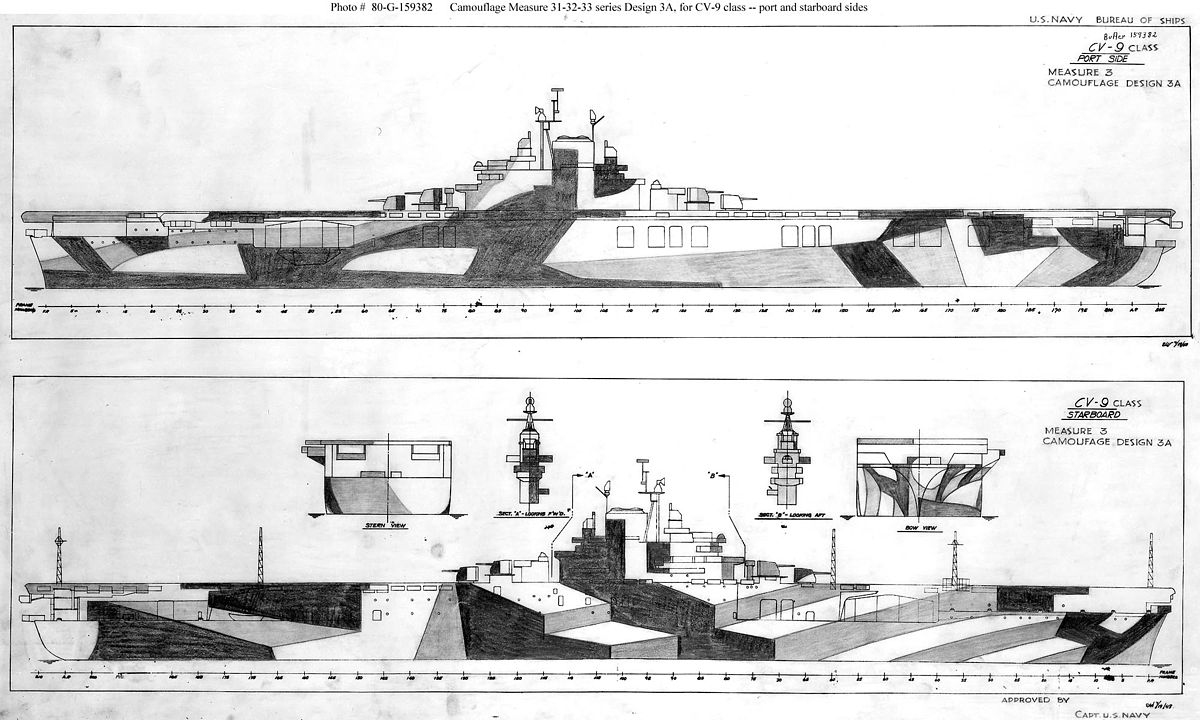

Well, of course the naval strategy that won the Pacific war, War Plan Orange and its successors, was drawn up and wargamed in the 1930s. But at the operational level, nothing prepared the Navy to employ the explosion of naval production that took place in 1943 and 1944. Fifteen fast aircraft carriers were put into commission in 1943. Thus was born the idea of a single carrier task force composed of three- and four-carrier task groups. The ability to concentrate or disperse gave Spruance and his carrier boss, Marc Mitscher, tremendous flexibility.

They realized during the February 1944 strike on Truk Atoll that it was no longer necessary to hit and run. There had been no precedent for this. Instead of hitting and running, relying on mobility and surprise, they could hit and stay, relying on sheer combat power, both offensive and defensive. That changed everything.

By the time the Fifth Fleet wrapped up the conquest of Guam, the carrier fleet was both an irresistible force and an immovable object. That was a function of a sudden surplus of hulls, and the innovations that the air admiralty proved up on the fly in the first half of 1944. Most of these involved making best use of the new Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat, fleet air defense, shipboard fighter direction, division of labor among carriers (for combat air patrol, search, and strike), armed search missions (rocket- and bomb-equipped Hellcats), the concept of the fighter sweep, adjusting the makeup of air groups to be fighter-heavy, night search and night fighting, and so on.

Just as important was the surge in amphibious shipping. In 1943, more than 21,000 new ‘phibs were launched of all sizes. The next year, that number surpassed 37,000. That’s the “fleet at flood tide” of my title. As Chester Nimitz himself noted, the final stage of the greatest sea war in history commenced in the Marianas, which became its fulcrum. Neither Iwo Jima nor Okinawa obviated that. And that concept is the conceit of my book and its contribution, I suppose—the centrality of the Marianas campaign, and how it changed warfare and produced America’s position in the world as an atomic superpower.

Spruance, King, Halsey, Tibbets, Turner –– all of them are giant military historical figures. After diving into the lives of these men, what surprised you? Did you go in with assumptions or prior knowledge about their personalities or behavior that changed over the course of writing this book?

I had never fully understood the size of Raymond Spruance’s warrior’s heart. I just mentioned the Truk strikes. Did you know that in the midst of it, Spruance detached the USS New Jersey and Iowa, two heavy cruisers, and a quartet of destroyers from Mitscher’s task force, took tactical command, and went hunting cripples? This was an inadvisable and even reckless thing for a fleet commander to do. He and his staff were unprepared to conduct tactical action. But he couldn’t resist the chance to seize a last grasp at history, to lead battleships in combat in neutering Japan’s greatest forward-area naval base.

Also, I hadn’t known how much Spruance exulted in the suicide death on Saipan of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, the executioner of the Pearl Harbor strike and Spruance’s opponent at Midway. Finally, I was unaware of the extent of his physical courage. Off Okinawa, in the space of two weeks in May 1945, two of his flagships, the Indianapolis and New Mexico, were hit by kamikazes. In the latter, he disappeared into the burning wreckage of the superstructure, to the horror of his staff, and turned up shortly afterward manning a fire hose. That’s a style of leadership that the “cautious” COMFIFTHFLT is seldom credited for.

Regarding Tibbets, I mentioned his near court-martial in North Africa. Few people know this happened, or even that he served in Europe at all, but he was among the finest B-17 squadron commanders in the ETO in 1942. The lesson of his near downfall is: Never mess with a line officer who’s destined to become a four star. This would be Lauris Norstad, Tibbets’s operations officer in North Africa, who went on to become one of the most important USAF generals of the Cold War.

You touch on this in your book, but the war stressed all of these men greatly. And each of them handled it in their own way. Taking just Spruance and Tibbets as examples, how did they handle the loss of men and the toll of war?

Spruance, in his correspondence, often described war as an intellectual puzzle. He could be hard-hearted. Shortly after the flag went up on Mount Suribachi, he wrote his wife, “I understand some of the sob fraternity back home have been raising the devil about our casualties on Iwo. I would have thought that by this time they would have learned that you can’t make war on a tough, fanatical enemy like the Japs without our people getting hurt and killed.” That’s a phrase worthy of Halsey: the sob fraternity. And yet when he toured the base hospitals, he felt deeply for the wounded in war.

It was for this reason that Spruance opposed the idea of landing troops in Japan. He favored the Navy’s preference for blockade. But those were perfectly exhausting operations at sea, week after week of launching strikes against airdromes in Western Pacific island strongholds, and in the home islands themselves. By the time Admiral Halsey relieved Spruance at Okinawa in May 1945, Spruance was exhausted both physically and morally.

Paul Tibbets suffered losses of his men in Europe, but in the Pacific he was stuck in a training cycle that ended only at Hiroshima on August 6. Later in life, he considered the mass death and destruction he wrought as an irretrievable necessity. Responding to those who considered waging total war against civilian targets an abomination of morals, Tibbets would say, “Those people never had their balls on that cold, hard anvil.” I don’t think the moral objectors have ever fully credited either the tragic necessity or the specific success of the mission of the atomic bomb program: turning Emperor Hirohito’s heart. Tibbets was always unsentimental about it.

Why is Spruance considered a genius?

He was the ultimate planner, and through his excellence in planning, naval operations became more than operational or tactical. They became strategic, war-ending. It was no accident that Raymond Spruance planned and carried out every major amphibious operation in the Western Pacific except for the one that invited real disaster, Leyte. He was in style, temperament, and talent a reflection of his mentor, Chester Nimitz. The Japanese gave him the ultimate compliment. Admiral Junichi Ozawa told an interviewer after the war that Spruance was “impossible to trap.”

Switching gears a bit, what is your favorite naval history book?

It’s a long list, probably led by Samuel Eliot Morison’s volume 5, Guadalcanal, but I’m going to put three ahead of him as a personal matter: Tin Cans by Theodore Roscoe, Japanese Destroyer Captain by Tameichi Hara, and Baa Baa Black Sheep by Gregory Boyington. This selection may underwhelm your readers who are big on theory, doctrine, and analytical history, but I list them unapologetically. These were the books that set me on fire with passion for the story of the Pacific War when I was, like, twelve. If I hadn’t read them at that young age, I don’t think I would be writing today. It is only a bonus that all three were published by the company that’s publishing me today, Bantam/Ballantine. We are upholding a tradition!

What is your research and writing process like?

It’s all an elaborate moonlighting gig, conducted in relation to, but apart from, my other work in book publishing. It takes me a while to get these done in my free time, which is stolen mostly from my generous and long-abiding wife, Sharon, and our family. But basically the process looks like this: I turn on my shop-strength vacuum cleaner, snap on the largest, widest attachment, and collect material for 18 to 24 months before I even think about writing. Having collated my notes and organized my data, I then dive into the fitful process of making this rough assemblage readable and smooth, envisioning multiple readers, from expert navalists to my dear mother, with every sentence I type. I stay on that task, early mornings and weekends, for maybe 18 more months. Then, in the case of The Fleet at Flood Tide, my editor and I beat the draft around through two or three revisions before it was finally given to the Random House production editor. Then we sweat over photos and maps. History to me is intensively visual, both in the writing and in the illustrating, so this is a major emphasis for me all along the way. I never offload any of this work to a research staff.

What’s next? Are you already thinking about what you want to write about after you finish the book tour and publicity for The Fleet at Flood Tide? Do you have a specific subject in mind?

One word and one numeral: Post-1945.

Last question. A lot of our readers here at the CIMSEC are also writers. What advice would you give to the aspiring naval historian?

Think big. Then think bigger. Then get started. And focus on people and all the interesting problems they’re facing.

James D. Hornfischer is the author of the New York Times bestsellers Neptune’s Inferno, Ship of Ghosts, and The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors, winner of the Samuel Eliot Morison Award. A native of Massachusetts and a graduate of Colgate University and the University of Texas School of Law, he lives in Austin, Texas.

Christopher Nelson is a naval officer stationed at the U.S. Pacific Fleet headquarters. A regular contributor to CIMSEC, he is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the U.S. Navy’s operational planning school, the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island. The questions and comments above are his own and do not reflect those of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

Featured Image: First Wave of U.S. Marines landing on Saipan. (USMC photo)