You may be wondering what an article about Afghanistan is doing on a site about maritime security. Well, I found myself asking a very similar questions when, within six months of joining the U.S. Navy and graduating from Officer Candidate School (OCS) in Pensacola, FL, I found myself in a land-locked country serving on a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) conducting counterinsurgency operations. The irony was not lost on me since I had joined very late in life (I was 35 when I went to OCS). The recruiter had said, “Join the Navy and see the world!” Little did I know we’d be starting in alphabetical order …

Meeting the requirements of an “individual augmentee” – (Fog a mirror? Check!) – and having just enough training to know how to spell “IO,” I arrived in Khost province in early 2008. I was fortunate to relieve a brilliant officer, Chris Weis, who had established a successful media and public diplomacy program and laid the groundwork for a number of future programs.

I decided that before setting out to win the “hearts and minds” of the local population, we needed to take stock of where we were and whether our efforts were achieving the effects we desired.

The goal of Information Operations (or “IO”) is to “influence, corrupt, disrupt, or usurp adversarial human and automated decision making while protecting our own.”[i] But how does one know whether the decision process, either human or automated, has actually been influenced in some way? We can assume or surmise that, based on the actions of the target of the IO campaign, some desired effect was achieved or not achieved. But how much of that was based on our IO campaign and how much on other factors, perhaps unknown even to us? We can also attempt to ask the target after the fact whether campaign activities influenced their decision making. But such opportunities might rarely arise in the midst of on-going operations.

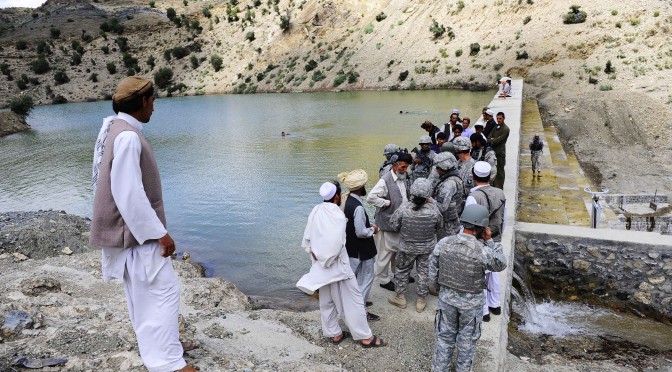

Commanders conducting counterinsurgency operations should have two primary IO targets: the insurgents and the local population. Retired U.S. Army officer John Nagl notes that “persuading the masses of people that the government is capable of providing essential services—and defeating the insurgents—is just as important” as enticing the insurgents to surrender and provide information on their comrades.[ii] A PRT is not charged with directly targeting insurgents. Instead, its mission is to build the capacity of the host government to provide governance, development, and these “essential services” for the local population.[iii]

Information Operations traditionally suffer from a lack of available metrics by which planners can assess their environment and measure the effectiveness of their programs. It may be impossible to show direct causation, or even correlation, between Information Operations and actual effects (i.e., did my influence program actually have its desired effect?). This often places IO practitioners at a distinct disadvantage when attempting to gain the confidence of unit commanders, who are tasked with allocating scarce battlefield resources and who are often skeptical of Information Operations as a whole.

Given these constraints it was clear that the PRT in Khost province, Afghanistan, needed a tool by which the leadership could benchmark current conditions and evaluate the information environment under which the population lived. We hoped that such a tool could help provide clues as to whether our IO (and the overall PRT) efforts were having the intended effects. As a result, we developed the Information Operations Environmental Assessment tool, which can be used and replicated at the unit level (battalion or less) by planners in order to establish an initial benchmark (where am I?) and measure progress toward achieving the IO program goals and objectives (where do I want to go?).

Since my crude attempt was first published in 2009, the U.S. Institute of Peace (yes, there is such a thing) developed the metrics framework under the name “Measuring Progress in Conflict Environments” or “MPICE.” This project seeks to:

provide a comprehensive capability for measuring progress during stabilization and reconstruction operations for subsequent integrated interagency and intergovernmental use. MPICE enables policymakers to establish a baseline before intervention and track progress toward stability and, ultimately, self-sustaining peace. The intention is to contribute to establishing realistic goals, focusing government efforts strategically, integrating interagency activities, and enhancing the prospects for attaining an enduring peace. This metrics framework supports strategic and operational planning cycles.

No doubt the MPICE framework is far more useful today than my rudimentary attempt to capture measures of effect in 2008, but I hope in some small way others have found a useful starting point. As I learned firsthand, and as practitioners of naval and maritime professions know, what happens on land often draws in those focused on the sea.

The author would like to thank Dr. Thomas H. Johnson and Barry Scott Zellen, both of the Naval Postgraduate School, for their professional mentorship and constructive advice, and for including my work in their book.

LT Robert “Jake” Bebber is an information warfare officer assigned to the staff of Commander, U.S. Cyber Command. He holds a Ph.D. in public policy from the University of Central Florida and lives with his wife, Dana and son, Vincent in Millersville, Maryland. The views expressed here are not those of the Department of Defense, the Navy or those of U.S. Cyber Command. He welcomes your comments at [email protected].