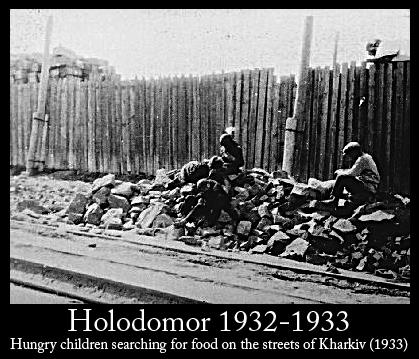

“I saw the ravages of the famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine- hordes of families in rags begging at the railway stations, the women lifting up to the compartment windows their starving brats, which, with dumbstruck limbs, big cadaverous heads and puffed bellies, looked like embryos out of alcohol bottles.”- Arthur Koestler (The God that Failed)

Background and History

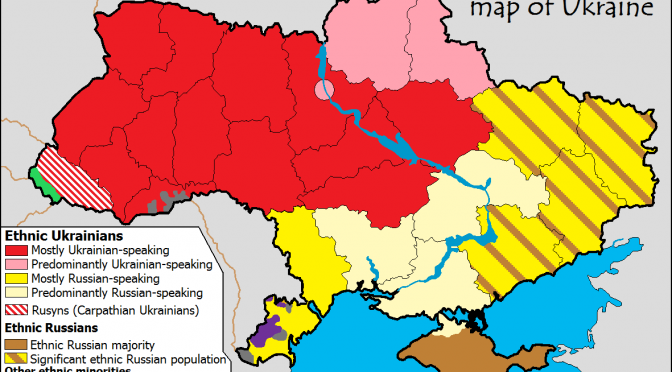

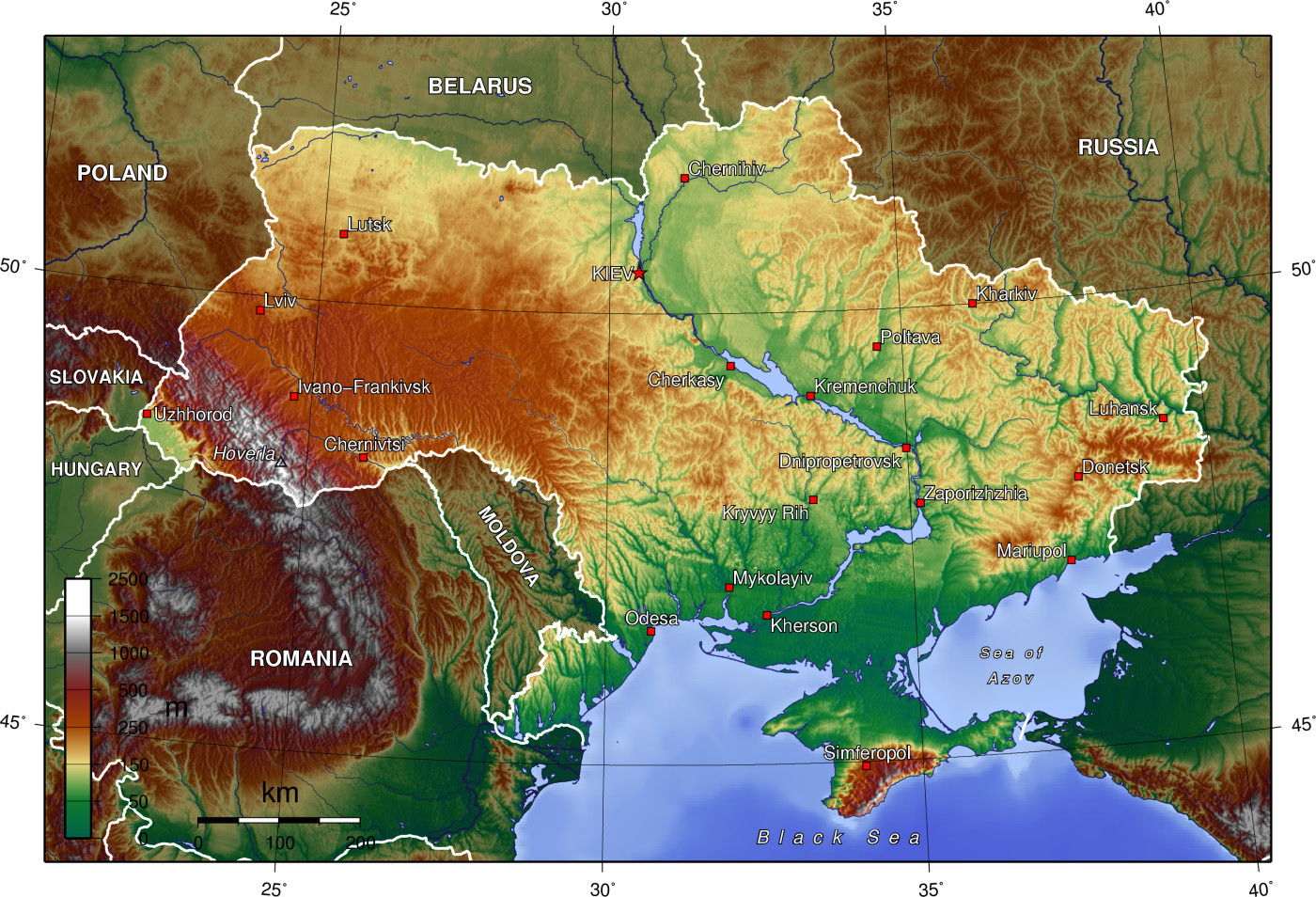

Ukraine has enjoyed true independence from Russia for only a short period of time in its history with the establishment of a republic after the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1991. For its entire history prior, it has been a vassal of Russian imperialists. Even the etymology of Ukraine translates roughly to Borderlands.[1] Through Russian and Soviet history, Ukrainian plains and farmland have served as a strategic breadbasket, with wars for control of the territory being fought not only by the Russians/Soviets, but Cossacks, Ruthenians (ancestors of modern Ukrainians), Poles, Lithuanians, Turks, Tartars, Swedes, Austro-Hungarians, and Germans.

The boundaries of the region of Ukraine through history are exactly what can be expected for a borderland… they are fuzzy. They have shifted east and west, north and south, with populations shifting over centuries, but with a center of gravity focused on a Ukrainian people. It was in the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 that Ukraine got its first glimpse of independence. Three powers emerged in the territory- the Organization for the Ukrainian Nation (OUN), the Cossack Hetmanate of Ukraine with the mandate of an imperial fiefdom, and the Bolshevik-associated Directorate of Ukraine. Ultimately in the Russian Civil War it was the Directorate that won the fight in Ukraine, establishing the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1919, and was formally admitted to the USSR in 1922.[2]

It was under the rule of the USSR and Joseph Stalin from 1932-1933 that this breadbasket faced the extreme measures that Russians would go to in order to ensure political domination. During the Holodomor (Death by Hunger), the Soviet government diverted food deemed “surplus” to other parts of the USSR, causing the deaths of somewhere between seven and twelve million Ukrainians.[3] The official Soviet census in 1926 showed a population of 29,018,817, with an estimated growth rate of 2.65%. By the time the next census was taken in 1939, there should have been a population of 40,770,506, however there was only a population of 30,946,218. That is a loss of over nine million people.[4]

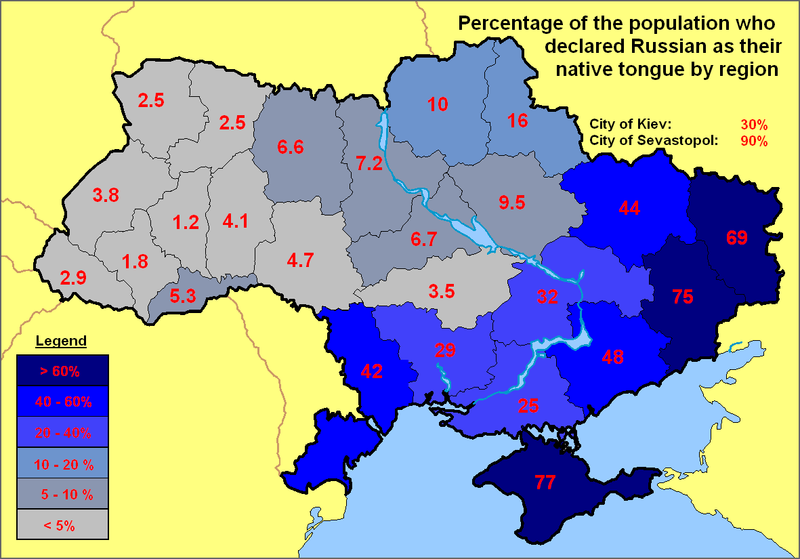

After the Holodomor the USSR pursued a policy of encouraging the migration of Russians into Ukraine. In 1926, Russians accounted for 9.2% of the Ukrainian population, while in 1939 Russians accounted for 13.4% of the Ukrainian population. After the transfer of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic from the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1954, the 1959 census showed Russians accounting for 16.9% of the Ukrainian population. By 1989, Russians accounted for 22.1% of Ukrainian population, and the Ukrainian census of 2001 showed Russians at 17.2% of the population, with political domination in the east of the country, and in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.[5] Since the Holodomor, the Russian population in Ukraine has doubled through the effects of the famine and Soviet migration policies.

Ukrainians continued to vie for independence throughout the Soviet era. Labeled as counter-revolutionaries and agents of the Bourgeoisie as a cover for continued domination,[6] the OUN in exile to Western Ukraine/Galicia (then part of Poland) continued to organize a fight for independence. That fight came with World War II when Poland was invaded. First, the USSR annexed Western Ukraine/Galicia into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (which remains part of Ukraine today), and then the German Wehrmacht Heer invaded the USSR. First were the Germans and their puppet government, then there were Ukrainian Soviet partisans, and then there was the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UIA)- militant wing of the OUN.[7] These entities fought a three-sided war. Later, with the formation of the United Nations (UN) in 1945, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic were included as separate founding nations, but their policies were controlled by Moscow, giving the USSR three votes in the General Assembly.[8]

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Ukraine declared its independence, but remained a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The question since that time was if Ukrainians would remain vassals to the Russian Federation, or would they begin to look west? Since independence, the Russian Federation has pursued a policy of ensuring Ukraine remains in their sphere. Of the four Presidents to serve in office, two of them were elected from the regions of Ukraine dominated by ethnic Russians. The first president, Dr. Leonid Kravchuk was a Western Ukrainian, and pursued policies that minimized Russian influence on newly independent Ukraine.[9] Both Leonid Kuchma[10] and Viktor Yanukovych[11] pursued policies bringing Ukraine closer to Russia, while the majority of Ukraine’s population supported joining the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

This clash reached critical mass for the first time during the 2004 Orange Revolution, which saw ethnic Ukrainian Viktor Yushchenko take the Presidency,[12] along with Yulia Tymoshenko as Prime Minister.[13] It was the poisoning of Yushchenko in particular that helped rally Ukrainians to the Ukrainian opposition coalition focused on breaking from Russian influence.[14] However, after years of administrative mismanagement and political infighting, Yanukovych and his Party of Regions regained power in 2010.[15] Tymoshenko, who ran for President in 2010 and was considered Yanukovych’s strongest potential opponent for the Presidency, was imprisoned on corruption charges in 2011.[16] This historical question of Russian influence on Ukraine and Ukrainian politics sets the stage for current events.

Euromaidan 2014

It was in 2013 that protests began when a widely supported political association and free trade agreement with the EU was not signed by President Yanukovych, after the Russian Federation offered Ukraine a 15 billion USD loan.[17] Those protests reached critical mass and became full riots in February 2014 at State Regional Administrative centers across Ukraine. The Kievan Maidan became a warzone, seeing Ukrainian Police Forces fighting an armed camp of protestors, with dozens of casualties and fatalities on both sides.[18]

On 22 February, the Yanukovych administration collapsed. Parliament turned on the ruling Party of Regions, impeaching and issuing arrest warrants for the President and Parliamentary leadership, with former Deputy Prime Minister Dr. Oleksandr Turchynov taking over as Acting President, [19] and former Foreign Minister Aresniy Yatsenyuk taking over as Acting Prime Minister.[20] Yanukovych has since fled to Rostov-on-Don, the administrative center of the Southern Federal District of the Russian Federation, with his security detail.[21] The new government also purged officials from the Party of Regions, as well as dissolved the Berkut (Riot Police).[22]

As political power shifted in Kiev, Russian President Vladimir Putin began to take a firmer tone on the turmoil in Ukraine. He ordered 150,000 Russian troops to begin exercises along Ukraine’s border.[23] Furthermore, Russian Naval Infantry troops began taking up positions outside of the Cossack Bay Naval Base, and an armed militia calling itself the Crimean People’s Brigade occupied strategic points around the Crimean Peninsula, raising the Russian flag over the Crimean Parliament in Sifremepol and two airports.[24]

Crimean People’s Brigade paramilitary holding positions outside Simferapol Airport. Photo Credit: CNN, http://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnn/dam/assets/140228065721-02-ukraine-0228-horizontal-gallery.jpg

The Current Situation

As of today escalation of the conflict is distinctly possible. The Ukrainian government announced that they had retaken airports and Parliament of Crimea with no casualties, and that the Armed Forces stands ready to defend Ukrainian territorial sovereignty. The Ukrainian government has also accused the Russian Armed Forces of already placing approximately 6,000 troops in Ukrainian territory. Later in the day, President Putin requested the Russian State Duma authorize the use of force in Ukraine for the purpose of restoring order and protecting Russian citizens, which is similar to the authorization for force in the Republic of Georgia in 2008. The United States and NATO in turn have warned the Russian Federation that interference with Ukraine would have consequences- although it is unclear if those consequences are diplomatic, economic, or military.[25]

Mr. Putin Does Not See Alaska from His House

President Putin has been quoted as saying that Ukraine is not an independent state, and for all intents and purposes,[26] except for some brief periods of time (1991-1994, and 2005-2011), he has been correct. Ukraine has had a voice, but that voice was controlled by Moscow. In his viewpoint, Ukraine is no different from any autonomous republic that is a subject of the Russian Federation, and its “independence” is merely a formality, such as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic’s vote in the UN General Assembly.

Ukraine is in essence considered not only a satellite of the Russian Federation but part of its territorial integrity. Any break with Moscow could therefore be seen as an existential threat to Russian sovereignty, let alone a break that sees Ukrainian membership in the EU and NATO. The center of Vladimir Putin’s political power lies in his strength as an executive, and maintaining influence over Ukraine plays a critical role in maintaining that strength.

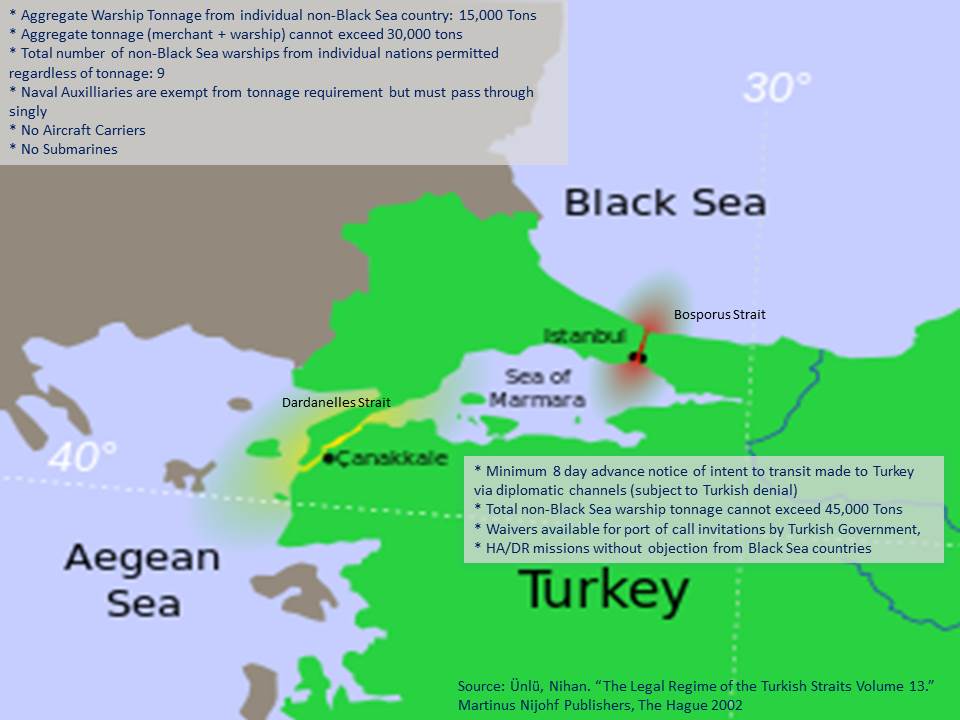

Furthermore, Ukraine plays a strategic role to the Russian Navy. The Crimea hosts one of the Russian Navy’s few warmwater ports, and the Crimean Peninsula itself is a strategic pivot point for the entire Black Sea, and serves as the Russian Navy’s logistical hub for projecting power into the Mediterranean Sea.[27]

In this case, President Putin is not concerned with the ambitions of the Ukrainian people, or sanctions that can be imposed on his state. The potential loss of Ukraine is an existential crisis both politically and militarily. The Russian Federation could tolerate diplomatic and economic sanctions. It has the largest territory of any independent state in the world, with 143 million people, and vast untapped natural resources.[28] Just as the USSR was able to develop isolated from the rest of the world,[29] so too could Vladimir Putin’s Russian Federation if it had to.

Policy Options: Do You Want the Rock or the Hard Place?

The United States has two options for actions that it can take: leave the issue alone or stand and fight for Ukrainians’ right for self-determination. Out of these two options there is a middle ground- mediating between the Russian Federation and Ukraine.

The first option is that the United States leaves Ukraine to fend for itself. Under this option the Russian Federation would launch a full invasion of the Ukraine once it became clear the United States would not intervene, and the maintenance of territorial sovereignty would be up to the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The Russian Armed Forces have 766 thousand personnel on active duty, and over two million in reserve; while the Ukrainians have 159 thousand personnel on active duty, and one million in reserve. The Russian Federation spends 4.4% of its GDP with a budget of 90.7 billion USD (32,381.29 USD per service member), while Ukraine spends 1.1% of its GDP with a budget of 1.9 billion USD (1,639.34 USD per service member).[30] In short, Russian troops will tend to have better quality training and equipment than their Ukrainian counterparts, and if Russian troops invade the Ukrainian Armed Forces may not be able to hold positions on the flat terrain that composes the majority of the country. The exception is in the Carpathian Mountains in the west of the country.

The main reason why the United States would not intervene would be primarily due to a lack of political will- war weariness from Afghanistan and Iraq. Such an action would have an effect on the American treasury and cost American lives if the Russian Federation does not decide to withdraw after American troops intervene. There would also be concerns if American troops, having not fought a conventional war since the 1990s, and having a force that came to age learning counterinsurgency will not fight effectively against Russian troops.

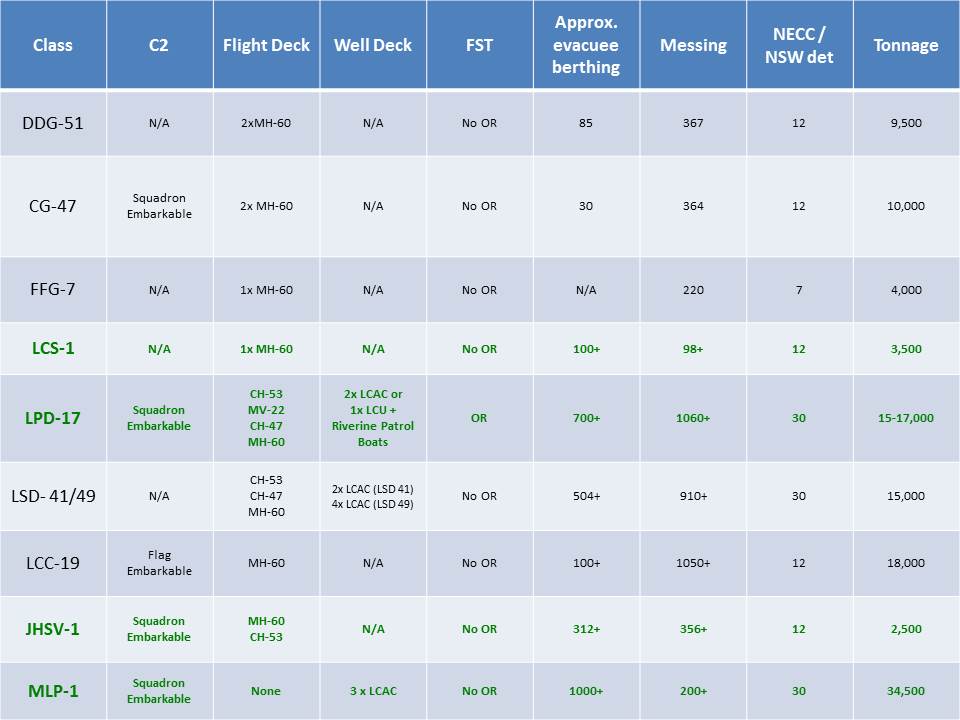

The second option is that the United States and NATO intervene to defend Ukraine against Russian aggression. In terms of ground forces, U.S. European Command (EUCOM) has the 2nd Stryker Cavalry Regiment, the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team, and the 12th Combat Aviation Brigade at its immediate disposal, with the 3rd Infantry Division and 1st BCT, 1st Cavalry Division are Regionally Aligned Forces stationed in the Continental United States. This adds up to a grand total of approximately 9,000 troops that can be used immediately, with an additional 21,000 that can be deployed shortly thereafter.[31] The best deployment of these limited ground forces would be for the 2nd Stryker Cavalry Regiment to be deployed to eastern Ukraine in order to serve as a deterrent for Russian ground forces. The 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team could be used to assist in isolating Russian forces on the Crimean Peninsula. A small force could hold the only land link to the rest of Ukraine, the Isthmus of Perekop, which is only 7 km wide at its widest, while a larger force could hold the Russian Black Sea Fleet’s Main Supply Route over land, the Kerch Strait Bridge, a chokepoint that connects the Crimean Peninsula to the Russian Federation. Aside from the American forces, the full weight of NATO’s military landpower can be focused on Ukraine.

The crux of support that EUCOM could provide to the Ukraine would be in terms of air and seapower. Allied Air Forces could establish expeditionary air bases both in Ukraine and in Romania that could be used to both support defense of Ukrainian airspace and transportation.[32] Additionally, the U.S. Army has one Patriot Missile battalion stationed in Germany to assist Ukrainian Air Defense Forces.[33] A NATO combined task force could then theoretically blockade the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Cossack Bay. The prospect or reality of the Russian Black Sea Fleet being humiliated by NATO naval and air forces, along with the possibility of a land invasion resulting in further escalation with a distinct possibility of a Russian military embarrassment after meeting NATO conventional forces of similar size, could hold a much worse political impact to Putin than not holding the Ukraine.

The third option is that the United States could focus on mediating between the Ukraine and the Russian Federation. This is the option where Ukraine might have to cede territory to the Russian Federation. Ethnic Russians get to maintain their ties to the Motherland, ethnic Ukrainians get to look westward, the Russian Federation maintains its naval installations, and avoids warfare that would prove economically devastating. In short everyone saves face. Such an option would involve negotiating either the direct transfer of territory or the offer of a referendum by administrative region. In the case of a direct transfer of territory, the low end of the offer could be the Crimean Peninsula, with the high end being the Russian regions of Ukraine. Under a referendum, Ukrainian Security Forces could ensure security of polling stations, with OSCE Observers validating results. The likely results would have Ukraine losing about a third to half of its territory to the Russian Federation, but in turn Ukraine would be free to determine its own fate, and the Russian Federation would save face.

Recommendation and Conclusion: Negotiate

Misguided pride in former glory is a poor reason to start a war, and it is important that as a matter of policy that allowing a war to be fought is the last option. It is also important to prevent Ukrainians from losing the independence they had sought for. The best option is the one where a solution is negotiated. Ukrainians want to break from the Russia Federation, but Russian Ukrainians want to remain with them. The best solution is to let the Russian Ukrainians go, and let the Russian Federation feel that their interests have been best served, while ensuring the Ukrainians are able to join with the EU and NATO. Using full force will only serve to harm American interests, while doing nothing will only encourage other actors to make bolder moves in the face of American power.

Robert C. Rasmussen is a graduate of the MA International Relations program at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs, and the CAS Security Studies program with SU’s Institute for National Security & Counterterrorism. He has served as a Fellow with the New York State Senate, and has interned with National Defense University’s Center for Complex Operations, and the U.S. Military Academy’s Network Science Center. He also serves as a Sergeant with the New York State Guard. The views in this article do not reflect those of the Department of Defense, the New York State Senate, or the NYS Division of Military & Naval Affairs.

[1] “Ukraine,” Online Etymological Dictionary, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=Ukraine&allowed_in_frame=0.

[2] “Ukrainian History: Chronological Table,” Guide to Ukraine, http://ukraine.uazone.net/.

[3] Davies, R.W., and S.G. Wheatcroft, “The Soviet Famine of 1932-33 and the Crisis in Agriculture,” Challenging Traditional Views of Russian History, ed. S.G. Wheatcroft, New York: MacMillan, 2002, 69-91.

[4] Figures based on estimated normal population growth rate compared with Census data.

[5] “Database.” Ukrainian Census Bureau, http://database.ukrcensus.gov.ua/MULT/Database/Census/databasetree_no_en.asp.

[6] Lenin, Vladimir I., “Hanging Order,” Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/archives/ad2kulak.html, 11 August 1918.

[7] Brooke, James, “Don’t Underestimate Ukraine,” Voice of America, http://blogs.voanews.com/russia-watch/2014/01/29/dont-underestimate-ukraine/, 29 January 2014.

[8] “Member States,” United Nations, http://www.un.org/en/members/growth.shtml.

[9] “Leonid Kravchuk,” President of Ukraine, http://www.president.gov.ua/en/content/history_kravchuk.html.

[10] Eke, Steven, “Profile: Leonid Kuchma,” BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/2283925.stm, 26 September 2002.

[11] “Profile: Ukraine’s Ousted President Viktor Yanukovych,” BBC News, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-25182830, 28 February 2014

[12] “Profile: Viktor Yushchenko,” BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4035789.stm, 13 January 2010.

[13] Profile: Yulia Tymoshenko,” BBC News, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-15249184, 22 February 2014.

[14] Rosenthal, Elisabeth, “Liberal Leader from Ukraine was Poisoned,” New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/12/international/europe/12ukraine.html?_r=0, 12 December 2004.

[15] Harding, Luke, “Yanukovych set to become President as Observers say Ukraine Election was Fair,” The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/feb/08/viktor-yanukovych-ukraine-president-election, 8 February 2010.

[16] Karimi, Faith, “Yulia Tymoshenko Walks out of Prison, and Back Into Ukrainian Politics,” CNN, http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/23/world/europe/ukraine-yulia-tymoshenko-profile/, 23 February 2014.

[17] Snyder, Timothy, “Don’t Let Putin Grab Ukraine,” New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/04/opinion/dont-let-putin-grab-ukraine.html?smid=tw-share&_r=0, 3 February 2014.

[18] “As It Happened: Ukrainian Police Storm Kiev Protest Camp,” BBC News, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26244542.

[19] Urquhart, Conal, “Ukraine MPs Appoint Interim President as Yanukovych Allies Dismissed- 23 February as it Happened,” http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/23/ukraine-crisis-yanukovych-tymoshenko-live-updates, 23 February 2014.

[20] Grytsenko, Oksana, “Arseniy Yatsenyuk Nominated to Lead New Government as Ukrainian Prime Minister,” http://www.kyivpost.com/content/politics/on-kyivs-independence-square-tonight-arseniy-yatseniuk-nominated-as-prime-minister-to-lead-new-government-337700.html, 27 February 2014.

[21] “Ousted Ukraine President Viktor Yankovych Appears at Russian Press Conference,” Wall Street Journal, http://live.wsj.com/video/viktor-yanukovych-resurfaces-in-russia/7DAD2A1D-7E35-4338-A838-CC5BB008D636.html#!7DAD2A1D-7E35-4338-A838-CC5BB008D636, 28 February 2014.

[22] Urquhart, Conal, “Ukraine MPs Appoint Interim President as Yanukovych Allies Dismissed- 23 February as it Happened,” http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/23/ukraine-crisis-yanukovych-tymoshenko-live-updates, 23 February 2014.

[23] Prentice, Alessandra, and Richard Balmforth, “New Ukrainian Ministers Proposed, Russian Troops on Alert,” Reuters, http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/02/26/us-ukraine-idUSBREA1G0OU20140226, 26 February 2014.

[24] Gumuchian, Marie-Louise, Laura Smith-Park and Ingrid Formanek, “Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Ukraine’s Crimea, Raise Russian Flag,” CNN, http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/27/world/europe/ukraine-politics/, 27 February 2014.

[25] Herszenhorn, David M., Mark Lander and Alison Smale, “With Military Moves Seen in Ukraine, Obama Warns Russia,” New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/01/world/europe/ukraine.html?hpw&rref=world, 28 February 2014.

[26] Marson, James, “Putin to the West: Hands Off Ukraine,” Time, http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1900838,00.html, 25 May 2009.

[27] Lally, Kathy, “Russian Forces in Ukraine: What Does the Black Sea Fleet Look Like?” Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/russia-decides-to-send-troops-into-crimea-what-does-the-black-sea-fleet-look-like/2014/03/01/38cf005c-a160-11e3-b8d8-94577ff66b28_story.html, 1 March 2014.

[28] Central Intelligence Agency, “Russian Federation,” CIA World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rs.html.

[29] Zickel, Raymond E., “The Russian Revolution & the Soviet Union,” The Soviet Union- a Country Study,” Ed. Raymond E. Zickel, Washington: Library of Congress, 1989, http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/Soviet1.html.

[30] “IISS Military Balance 2013,” International Institute for Strategic Studies.

[31] “Units and Commands,” U.S. Army, Europe, http://www.eur.army.mil/organization/units.htm.

[32] U.S. European Command, www.eucom.mil.

[33] “Units and Commands,” U.S. Army, Europe, http://www.eur.army.mil/organization/units.htm.