By David Van Dyk

“My boy, you will be nothing insignificant, but definitely something great, either for good or evil.” – School teacher of Themistocles

Since he was only a child, he knew he had always wanted the respect and recognition of his fellow citizens. He hungered for it, dreamt of it, and prepared for it. While all the other kids would play and laugh, he would study and write, spending countless hours practicing speeches in his home. His parents were of no special heritage, and royalty did not flow through his blood. In its place, determination coursed through his veins. Themistocles, an Athenian, knew he was meant for something great. History would show that Themistocles, when he became archon, encouraged a naval policy in Athens, and helped drive off the Persian Empire and secure a place of strength and resolve for Athens in the world. Ancient scholars and historians, like that of Plutarch and Herodotus, have documented his life, allowing a glimpse into the magnificence of his achievements. Modern day scholars have shed even more light, suggesting that it was Themistocles himself who saved the future of western civilization. Themistocles, the commander of the Athenian fleet, should be bestowed the title of the Father of Naval Warfare due to his understanding of the Persian Empire, the importance of naval supremacy, and his involvement in the political process.

If we are to understand the rise of Themistocles, then we must first understand the impacts of the Ionian Revolt. R.J. Lenardon, in The Saga of Themistocles, says the Ionian Revolt “was to have momentous consequences for all of Hellenes, not least the Athenians and Themistocles, during the first quarter of the fifth century.”1 How this revolt would shape both Athens and Persia would set the stage for the incredible life of the aspiring, but young, Themistocles.

In the year of 499 B.C., the Hellenes of Asia Minor realized they had experienced enough. The Ionians grew restless of the oppression of the Persian Empire, and decided to fight back. For over 30 years, the superpower of the world, Persia, had subjugated the Greek cities of Asia Minor under numerous tyrannies, forcing the Greeks to build the cities of Persia and further the dominion of their empire. Under the rule of King Darius, he “undertook a thorough and systematic political and financial reorganization of the Persian Empire.”2 With these sweeping changes now taking effect, Darius thought it a no better time than to expand the land and influence of the Persian Empire. Under his guidance, the Persians blazed their way through Europe, “campaigning successfully against the Thracians and even securing the allegiance of Macedonia.”3 While these accomplishments were impressive, the rising discontent of the Ionians against Persia grew. After failing to convince the Spartans to join their cause against Darius, the Ionians looked toward, as Herodotus says, “the next most powerful state” after Sparta, that of Athens.4

Herodotus writes, “After the Athenians had been won over, they voted to dispatch twenty ships to help the Ionians and appointed Melanthion, a man of the city who was distinguished in every respect, as commander over them.”5 Herodotus goes on to write in a flare of foreboding that “these ships would turn out to be the beginning of evils for … the barbarians.”6 After the allied contingent of the rebellion sailed to Sardis and burned the Persian city to the ground, the Athenians, due to heavy losses, withdrew from the fighting, and “they refused to help the Ionaians any further.”7 Yet their actions, with the help of the Ionians, would send Darius into a rage against the Athenians. Herodotus recounts a chilling tale:

“When it was reported to Darius that Sardis had been taken and burnt by the Athenians and Ionians and that Aristagoras the Milesian had been leader of the conspiracy for the making of this plan, he at first, it is said, took no account of the Ionians since he was sure that they would not go unpunished for their rebellion. Darius did, however, ask who the Athenians were, and after receiving the answer, he called for his bow. This he took and, placing an arrow on it, and shot it into the sky, praying as he sent it aloft, ‘O Zeus, grant me vengeance on the Athenians.’ Then he ordered one of his servants to say to him three times whenever dinner was set before him, ‘Master, remember the Athenians.’” 8

With the Athenian fleet now out of the picture, the Ionian Revolt began to wane. The final Persian push came at Miletus, where the Persian army and navy decided to disregard the more minor cities. Attacking the source of the rebellion, the Persians overtook the Ionians at Miletus and brought them under subjugation once again. The Ionian Revolt virtually ended, and the Persian Empire set about re-conquering the rest of the rebellious cities. This revolt had two major effects: The Persian Empire grew vastly in military power, and the wrath of Darius was now directed toward the Athenians. After all, how could he forget when he was reminded of their actions every time he sat down for dinner?

The Rise of Themistocles

After the successful defeat of the Ionian Revolt in 494 BC, Darius began his march toward Athens. Herodotus’ first mention of Themistocles comes on the heels of the advance of the Persian Empire on all of Hellas after its crushing defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. Around 480 BC, after attempting to discern a prophecy from an Oracle, the people of Athens were disturbed as to its cryptic meaning, fearing the gods had predicted their end. “But among the Athenians was a certain man who had just recently come into the highest prominence; his name was Themistocles, and he was called the son of Neokles.”9 Themistocles convinced his fellow Athenians that the Oracle, in summary, was urging them to meet the Persians at sea. According to several ancient sources, the Oracle had spoken of “wooden walls,” and Themistocles used this interpretation to his advantage in his advising of a naval policy.

However, around 483 BC when Athens was receiving large revenues from lucrative silver mines, Themistocles spoke to the government urging them to spend the increased revenue on their naval fleet. For a long time, Athens was at war with Aegina, who had sided with the Persian Empire in providing them “earth and water.”10 Themistocles saw Aegina as the perfect pretext to build up the Athenian fleet, knowing full well that Athens would need this fleet to face the coming onslaught of the Persian Empire. Plutarch, in his biography of Themistocles in Lives, recounts this tale as well:

“And so, in the first place, whereas the Athenians were wont to divide up among themselves the revenue coming from the silver mines at Laureium, [Themistocles], and he alone, dared to come before the people with a motion that this division be given up, and that with these moneys triremes be constructed for the war against Aegina. This was the fiercest war then troubling Hellas, and the islanders controlled the sea, owing to the number of their ships.”11

Plutarch, in the text above, points out one of the earliest examples of Themistocles’ lobbying for a powerful navy. Calum M. Carmichael, in Historical Methods, makes note of the importance of the Athenian navy as a whole from the years of 480 – 322 BC:

“Of all the public services, the naval [public office] … was arguably the most important. It directly served the strategic and commercial interests of the state: the duties centered on the command and maintenance of the trireme warship for a year. It involved a large outlay: maintaining a single ship could require expenditure in excess of one talent, whereas other liturgies required half as much or less. And, more than any other public service, the naval liturgy was an object of reform throughout the democratic period.”12

As a result of Themistocles’ lobbying, Athens devoted their increased revenues to the building up of the Athenian navy, thus establishing themselves as a powerhouse among the Greek city-states. However, his policies were not met with unanimous praise. Plutarch makes note of it, saying, “…he made [Athenian warriors], instead of ‘steadfast hoplites’ – to quote Plato’s words, sea-tossed mariners, and brought down upon himself this accusation: ‘Themistocles robbed his fellow-citizens of spear and shield, and degraded the people of Athens to the rowing-pad and the oar.’”13

Yet Themistocles continued with his naval buildup. As he spoke to the Athenians concerning the Oracle’s cryptic message, he convinced them that rather than run and hide from the coming enemy, their salvation would come from the sea. Having just recently built up their naval power through the increased revenues from the silver mines, Themistocles capitalized on the moment, understanding that it was through naval power and not ground forces that would drive back the Persian Empire. Yet to fully grasp the sharp intellect of Themistocles as a naval advocate, we need to go back in time to 493 BC, when Themistocles found himself as archon of Athens, a perfect time to begin his march to the ocean.

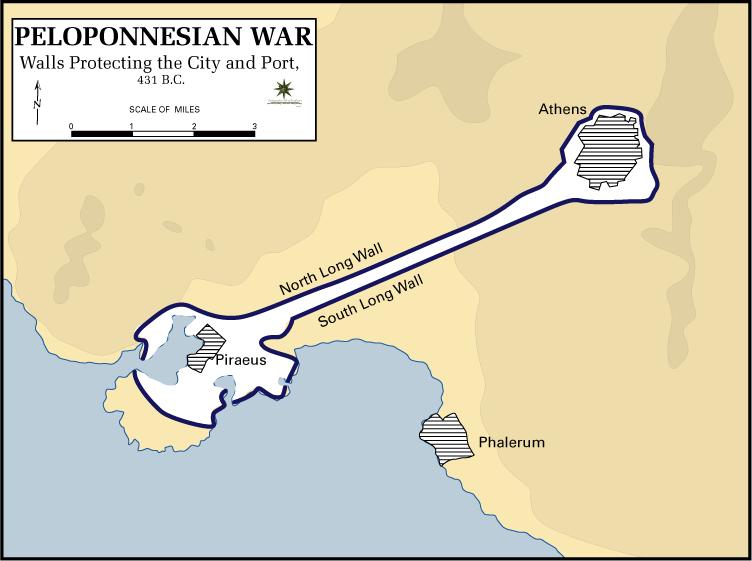

Lenardan, in Saga of Themistocles, says, “Dionysius of Halicarnassus tells us that Themistocles was archon at Athens in 493 BC, and the chronographic tradition recorded by Eusebius lends particular support to the assumption encouraged by other evidence that it was as archon in that very year that he began the fortifications of the Piraeus.”14 Themistocles was familiar with the advantage of the Piraeus. This natural harbor provided three ports that had far more strategic value than the smaller Bay of Phalerum that the Athenians were using at the time. Tom Holland, in Persian Fire, says this of Themistocles’ genius:

“Drawing up his manifesto, he began to argue for the urgent down-grading of the existing docks and their replacement by a new port at Piraeus, the rocky headland that lay just beyond Phalerum beach. The shoreline there afforded not one but three natural harbors, enough for any fleet, and readily fortifiable. True, it lay two miles further from the city than Phalerum, but Themistocles argued passionately that this was a small price to pay for the immense advantages that a new harbor at Piraeus would afford: a safe port for the Athenians’ ever-expanding merchant fleet; a trading hub to rival Corinth and Aegina and immunity from Aeginetan privateers.”15

Themistocles understood that trading the convenience of Phalerum for the strategic position of Piraeus was well worth the trade-off. Whether Themistocles began this project during his archonship, or if he started it later, possibly around 483 or 479 BC, is debated among modern-day scholars. Cornelius Nepos, a Roman historian who lived from 110 BC to 25 BC, says this of Themistocles’ involvement with the building of the port at Piraeus: “Themistocles was great in the war [at Salamis], and was not less distinguished in peace; for as the Athenians used the harbor of Phalerum, which was neither large nor convenient, the triple port of the Piraeeus [sic] was constructed by his advice, and enclosed with walls, so that it equaled the city in magnificence, and excelled it in utility.”16 Nepos dates the building up of Piraeus after the Battle at Salamis in 480 BC, and makes no mention of it being started during the time of Themistocles’ archonship. Plutarch also writes “After [he built the walls of Athens] he equipped the Piraeus, because he had noticed the favorable shape of its harbors, and wished to attach the whole city to the sea; thus in a certain manner counteracting the policies of the ancient Athenian kings.” 17

However, there is no reason not to suggest that Themistocles initiated the building of the Piraeus while he was archon. Having desired to build up the naval prestige of Athens as soon as he could, he very well could have looked to the promising port during his early days in office. The National Hellenic Research Foundation appears to solidify this belief: “Thus, within only one year, Athens and the northern part of Acropolis received new fortifications, which incorporated the older building’s pieces and offerings, even tombstones, while beginning the completion of the fortification of the Piraeus port, already launched by Themistocles himself as the 493 BC ruler.”18 The building of the Piraeus port allowed the Athenians a superior advantage in their conquest to become masters of the sea. By encouraging the Athenians to move their current harbor to a more secure one, Themistocles once again proved his intellect in understanding the multiple facets of naval power. He had built up a strong fleet through the use of increased revenue from the state, and moved the focus of their sea power to a safer, more strategic area.

What may be more impressive than anything else was his foresight. During the time after the Battle of Marathon, many believed that the Persians were defeated and would not come back. Lenardon makes mention of this: “Most of the Athenians believed that the defeat of the Persians at Marathon meant the end of the war; but Themistocles realized it was only the beginning of greater struggles.”19 Themistocles understood that after the death of Darius, Xerxes would seek vengeance, and it would come swifter and stronger than the last battle at Marathon. Themistocles had his fleet, and the construction of the Piraeus port was nearing completion. Now, he would test the resolve and courage of his fellow allies in battle at Salamis.

At the Battle of Salamis, we encounter first-hand the intellect and courage of Themistocles, now the commander of the Greek allied fleet. His exploits here are perhaps what has made him become the legend he is today.

Manipulating the Enemy

When the Greek allied fleet converged at Salamis, it was the largest contingent to have assembled. Thucydides accounts for the navies present:

“For after these there were no navies of any account in Hellas till the expedition of Xerxes; Aegina, Athens, and others may have possessed a few vessels, but they were principally fifty-oars. It was quite at the end of this period that the war with Aegina and the prospect of the barbarian invasion enabled Themistocles to persuade the Athenians to build the fleet with which they fought at Salamis; and even these vessels had not complete decks. The navies, then, of the Hellenes during the period we have traversed were what I have described. All their insignificance did not prevent their being an element of the greatest power to those who cultivated them, alike in revenue and in dominion.”20

Yet the admirals that were also in command of the Greek allied fleet were nervous and unsure. They believed that rather than fight the Persian fleet at Salamis where the Persian army was gathering, they would turn and sail toward the Isthmus at Peloponnese, and defend the city-state of Sparta from there. But Themistocles understood that the only way to defeat the Persian navy was to use their vast numbers against them. The straits and narrow passages at Salamis would force the Persian navy to thin their numbers in order to pass through the waters. From this vantage point, the Greek allied fleet could inflict serious damages on the Persians. Knowing this, Themistocles sent a messenger in secret to the Persian commanders. Herodotus narrates the story, writing that the messenger, acting as a defector, informed the Persian commanders that the Greek fleet was in disarray and unsure of themselves. Encouraging the Persians that now was the time to strike, he “made a quick departure” from the Persian navy.21

The Persian generals, eager to crush the Greek allied fleet and sail through to Athens and then Sparta, chomped on the bait, hoisted the sails, and sliced through the waters to Salamis. Themistocles was then alerted by a scout that the Persian navy was upon them, and the Greek allied fleet would need to make their stand at Salamis. Themistocles’ plan had worked. The fate of Athens, and the future of Greece, would rest at Salamis.

A Fitting Father Figure

Because of the cunning and intellect of Themistocles, the Greek allied fleet won a decisive victory at Salamis. The Persian navy found an organized and battle-ready Greek fleet, and the narrow passages of Salamis proved too narrow for the great numbers of Persian ships. The Greeks drove back the advance of the Persian Empire once again, reminding Xerxes of an earlier time, when his father, Darius, was defeated at Marathon.

Herodotus recounts, “Thus it was concerning them. But the majority of [Xerxes’] ships at Salamis were sunk, some destroyed by the Athenians, some by the Aeginetans. Since the Hellenes fought in an orderly fashion by line, but the barbarians were no longer in position and did nothing with forethought, it was likely to turn out as it did.”22

Xerxes’ final push came with the culmination of the land battle at Plataea and the naval battle at Mycale around 479 BC. There, the Greeks destroyed the advances of the Persian forces, and Xerxes retreated back into his homeland.

Modern day scholars, like that of Victor Davis Hanson, an internationally recognized military historian, have credited the battle at Salamis as “one of the most significant battles in human history.”23 Thucydides, in his landmark work of History of the Peloponnesian War, has this to say of Themistocles:

“Themistocles was a man who exhibited the most indubitable signs of genius; indeed, in this particular [war], he has a claim on our admiration quite extraordinary and unparalleled. By his own native capacity, alike unformed and unsupplemented by study, he was at once the best judge in those sudden crises which admit of little or of no deliberation, and the best prophet of the future, even to its most distant possibilities.”24

In earning such praise and admiration from his peers, Themistocles was made a legend. His knowledge and wisdom in naval warfare gave Athens the upper hand against the Persian Empire and, as scholars have argued, saved the future of western civilization. Should the Persian Empire have sacked Athens and Sparta, it would have immediately halted the advance of the Greek city-states. From there, Xerxes would have swept into Europe. But, “among the Athenians was a certain man who had just recently come into the highest prominence; his name was Themistocles.” It would only be fitting then that Thucydides, the Father of Scientific History, would write of the exploits and glories of Themistocles, as this author proposes, the Father of Naval Warfare.

David Van Dyk is a graduate of Liberty University with a Bachelor’s of Science in Communications Studies and a member of the Lambda Pi Eta honor society. He is currently pursuing a Master’s in Public Policy with a focus in International Affairs at the Helms School of Government. He can be reached at dvandyk@liberty.edu.

References

1. Robert J. Lenardon, The Saga Of Themistocles, London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Robert B. Strassler, The Landmark Herodotus: the Histories, New York: Anchor Books, 2009.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Lives: Themistocles And Camillus, Aristides and Cato Major, Cimon and Lucullus, 1 Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1914.

12. Calum M. Carmichael, “Managing Munificence,”Historical Methods 42, no. 3: 83, 2009.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Cornelius Neps, Cornelius Nepos: Lives Of Eminent Commanders, The Tertullian Project, 1886.

17. Ibid.

18. “The Walls Of Athens” National Hellenic Research Foundation, October 27, 2009, http://www.eie.gr/archaeologia/gr/02_deltia/fortification_walls.aspx.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Victor Davis Hanson, Carnage And Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power, New York: Doubleday, 2001.

24. The Peloponnesian War, London, J. M. Dent: New York, E. P. Dutton, 1910.

Featured Image: Statue of Themistocles in Piraeus, Greece. (Vassilis Triantafyllidis – www.LemnosExplorer.com)