By Kelly Moss

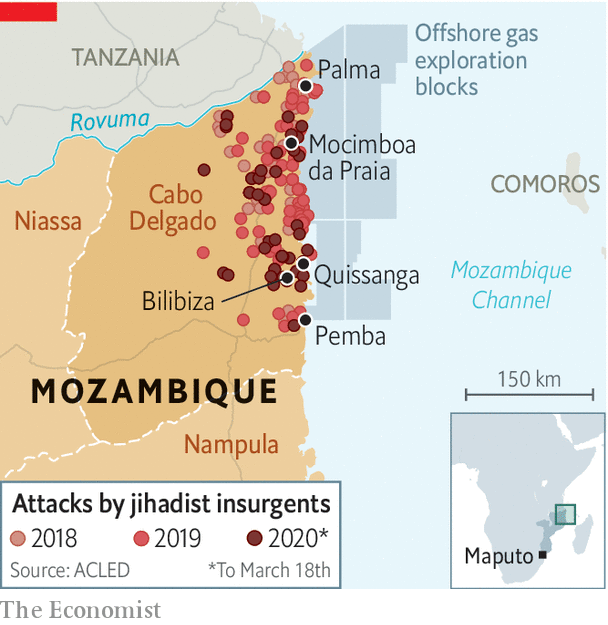

Two months ago, the insurgent group Ahlu Sunna Wal Jamaa (“Ansar al-Sunna”) attacked the strategic port of Mocímboa da Praia in Mozambique for the second time in six months. Unlike the day-long siege on March 23rd, Ansar al-Sunna has occupied Mocímboa da Praia since August 13th, indicating a significant escalation in insurgent capabilities.

Ansar al-Sunna was established in Mozambique in 2015 and became increasingly violent beginning in October 2017. Attacks have centered on the Cabo Delgado province, where the group originated, particularly the coastal town of Mocímboa da Praia. Despite having a formal affiliation to the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province, the insurgency finds deeper roots in local socio-economic and political grievances stemming from an emerging and exploitative regional liquified natural gas industry, and perceived and actual political marginalization by the state, amongst other things. However, the insurgency has reportedly seen incoming recruits from other East African countries, raising concerns over the potential regionalization of this primarily local conflict.

Regardless, the Mozambican government’s repressive response, eerily similar to tactics used in Nigeria’s counterterrorism campaign against Boko Haram, has only served to stoke domestic tensions and fuel anti-state propaganda in support of Ansar al-Sunna. In terms of maritime capabilities, Stable Seas’ new report, Violence at Sea: How Terrorists, Insurgents, and Other Extremists Exploit the Maritime Domain, demonstrates that since March, Ansar al-Sunna has increasingly used the sea for operational and financial purposes, including moving supplies and fighters for tactical support, targeting ports and coastal communities, and exploiting pre-existing maritime-enabled illicit trafficking networks for funding.

This story is much bigger than Ansar al-Sunna’s most recent attacks. Speculation over Mozambique’s response to the group, particularly discussions of regional engagement by the Southern African Development Community and South African Navy, raises questions about the role of the maritime domain in countering Ansar al-Sunna, highlighting the importance of strong national maritime enforcement capacity and its pivotal role in countering violent non-state actors (VNSAs) globally.

The Criticality of Maritime Enforcement Capacity

Maritime Enforcement Capacity (MEC) can be broadly defined as the ability of a state to effectively monitor its territorial waters and exclusive economic zones, and enforce maritime legislation, including those targeting trafficking networks and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. States with high MEC can successfully interdict transnational criminal actors, conduct operations, and patrol their waters to defend against intra- and inter-regional threats, and respond in real time to maritime-based threats. Absent strong MEC, even the most well-developed maritime security legislation is rendered effectively useless – a fact willingly and aggressively exploited by nefarious actors.

Enter Mozambique. With a Stable Seas Maritime Security Index MEC score of 31, the fourth lowest in East and Southern Africa, Mozambique’s control over its territorial waters and related activities is severely limited. This is largely due to an underdeveloped navy with limited operational capacity to enforce maritime security along the Mozambican coast, the fourth longest in Africa. According to multiple sources, domestic naval operations are slim due to a lack of serviceable assets (12 patrol and coastal combatant vessels), exacerbated by a lack of available fuel for training missions. Furthermore, naval personnel estimates are small compared to the rest of the Mozambique Defense Armed Forces (FADM), with 2020 estimates suggesting 200 active naval officers out of 11,200 FADM troops.

To attempt to boost this low MEC, the Mozambican government has taken steps toward improvement, including asset procurement, regional exercise participation, and bilateral maritime cooperation agreements. Regarding assets, Mozambique purchased three HSI 32 Interceptor naval patrol vessels from France in early 2016 and was donated 10 speedboats and two other fast interceptor boats, along with military training, from Portugal and India in 2018 and 2019. Mozambique also routinely participates in regionally-led trainings with other East African Djibouti Code of Conduct signatories, as well as maritime security trainings by the International Maritime Organization and Cutlass Express, a maritime training exercise for East African countries that is supported by U.S. Africa Command and U.S. Naval Forces Africa. Additionally, Mozambique has recently pursued bilateral maritime cooperation agreements with Italy, India, and Seychelles. Despite these laudable efforts, MEC remains limited, as demonstrated by the recent inability of the FADM to defend and reclaim control of Mocímboa da Praia’s port from Ansar al-Sunna.

Weak Maritime Enforcement Capacity Emboldens VNSAs

So what does MEC have to do with VNSAs like Ansar al-Sunna? Weak MEC emboldens VNSAs both directly and indirectly, thereby allowing them to exploit diminished interdiction capabilities, limited operational assets, and strategic confusion.

Weak Interdiction Capacity

Weak interdiction capabilities facilitate illicit trades, contributing to the sustainability and longevity of VNSAs. A key dimension of MEC is the ability of states to apprehend illicit products that are trafficked to ports (via containerized shipments) and offshore landing sites (via small dhows). Due to Ansar al-Sunna’s elusive nature, speculation abounds as to where the group’s funding streams lie, but it is believed that illicit trades play at least some role. This is reinforced by the fact that Mocímboa da Praia is a longstanding hub for these types of trades. Of the numerous illicit trafficking networks in the region (timber, rubies, wildlife, gold, etc.), narcotics are the most likely industry for Ansar al-Sunna engagement, according to the Global Initiative for Transnational Crime. Indeed, one of the world’s largest heroin trafficking routes spans Africa’s east coast from Pakistan to South Africa. Mozambique is a key transit point on that route, one that has been increasing in recent years, per the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. While it is unlikely that Ansar al-Sunna has been able to fully infiltrate these markets, the group likely has control over some coastal landing sites in the area, allowing them to levy taxes on heroin, as well as other illicit products. These funds can then be used to procure arms, recruit individuals, and finance operations. Should Ansar al-Sunna retain control of Mocímboa’s port in the long-term, these funding streams could increase.

To increase interdiction capabilities, and by extension MEC, Mozambique and other states should focus on strengthening port inspection processes and training relevant authorities, addressing domestic corruption that allows illicit goods to flow through major ports, and modernizing port technology to minimize vessel wait times that can result in insufficient inspections.

Limited Operational Assets

Limited operational assets and other domestic response capabilities make deterring and responding to maritime-based VNSA attacks difficult, leaving coastal areas vulnerable to attack. Responding in real-time to VNSA attacks requires the state to have adequate force numbers, weapons, and other assets. For attacks committed in the maritime domain, this means having serviceable vessels and a robust naval force, both of which are lacking in Mozambique. Without these, the state cannot thwart active attacks or deter VNSAs from exploiting the maritime domain for operational purposes. Even more concerning is when assets do exist, but training and institutional knowledge on how to actually use them is limited, hindering the utility of these vessels.

In Mozambique, this asset vulnerability has allowed Ansar al-Sunna to target coastal communities and military assets with little consequence, including the port in Mocímboa da Praia. In the August 13th attack, preliminary reports suggested that the group resupplied itself with weapons, fighters, and supplies via dhows, contributing to Ansar al-Sunna’s resilience. This tactical exploitation of the maritime domain has continued, resulting in attacks on numerous surrounding islands, including the September 9th attacks on Ilha Vamizi and Ilha Metundo. At this point, it is important to note that naval forces are not inherently necessary to disrupt attacks on ports, or on other land-based maritime assets, but that they are a useful deterrent mechanism, and in some cases, an integral response mechanism to VNSA attacks at sea.

While acquiring assets is the easiest way to improve the operational dimension of MEC, this is not feasible for certain states. Even when vessel acquisition is part of foreign maritime capacity-building efforts, this does not always translate to assistance with the operating costs of acquired vessels. In these situations of financial constraint, there is still room for improvement, including training land-based forces in amphibious warfare and basic port operations, providing robust technical training to armed forces on available and serviceable naval assets, and leveraging intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities to track VNSA activity before attacks happen. For Mozambique, this could involve leveraging the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Center in Madagascar.

Strategic Confusion

Domestic operational limitations make coordinating a strategic response to maritime-based VNSAs difficult, delaying response times, stoking regional tensions, and elevating group notoriety. When VNSAs execute significant attacks via the maritime domain and the targeted country is unable to adequately respond because of low MEC, uncertainty abounds as to what happens next. If the recipient country decides that it wants maritime assistance and support from other regional actors, independently or through a unified response, questions then arise as to whose responsibility this becomes.

For Mozambique, does the onus fall on regional actors with the strongest navies and coast guards, such as South Africa? As Leighton Luke raises, will the South African Development Community activate Articles 6 and 9 of their Mutual Defence Pact? Or will recent discussions about European Union involvement come to fruition? If so, will these forces be amphibious or primarily land-based? Who is ultimately responsible in countering VNSAs when the host country cannot? As this confusion and ambiguity abounds, drawing the attention of regional and international actors, VNSAs reap benefits. In the case of Ansar al-Sunna, regional discussions since May and the onslaught of international attention amidst a continuing occupation since August 13th has lent the previously little-known group from northern Mozambique international legitimacy and notoriety.

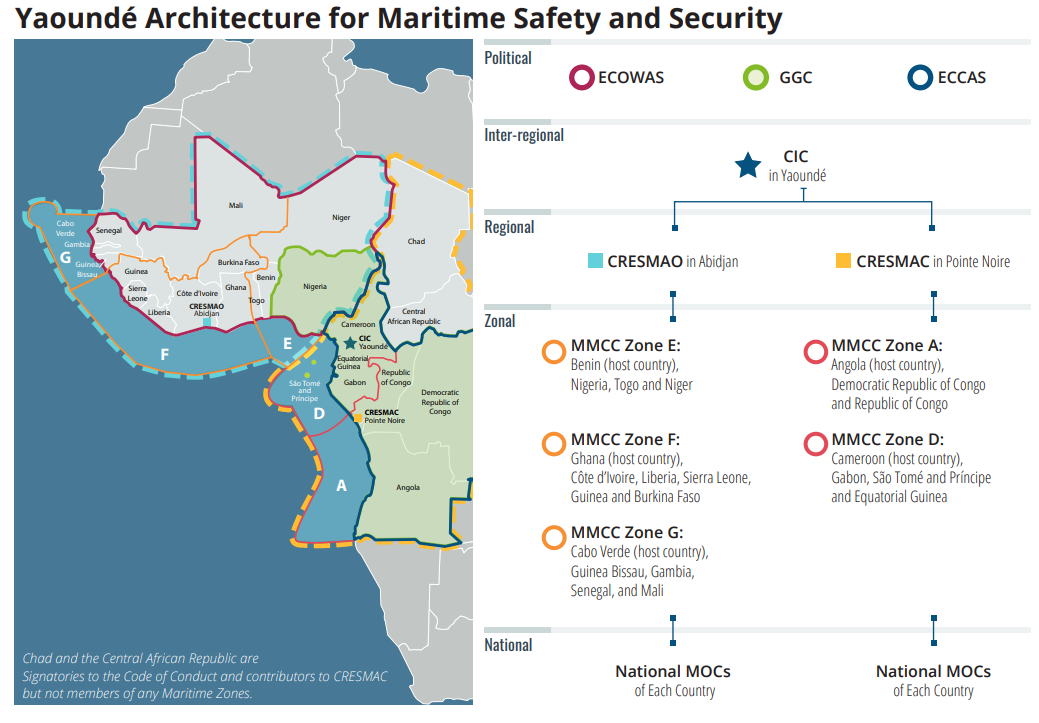

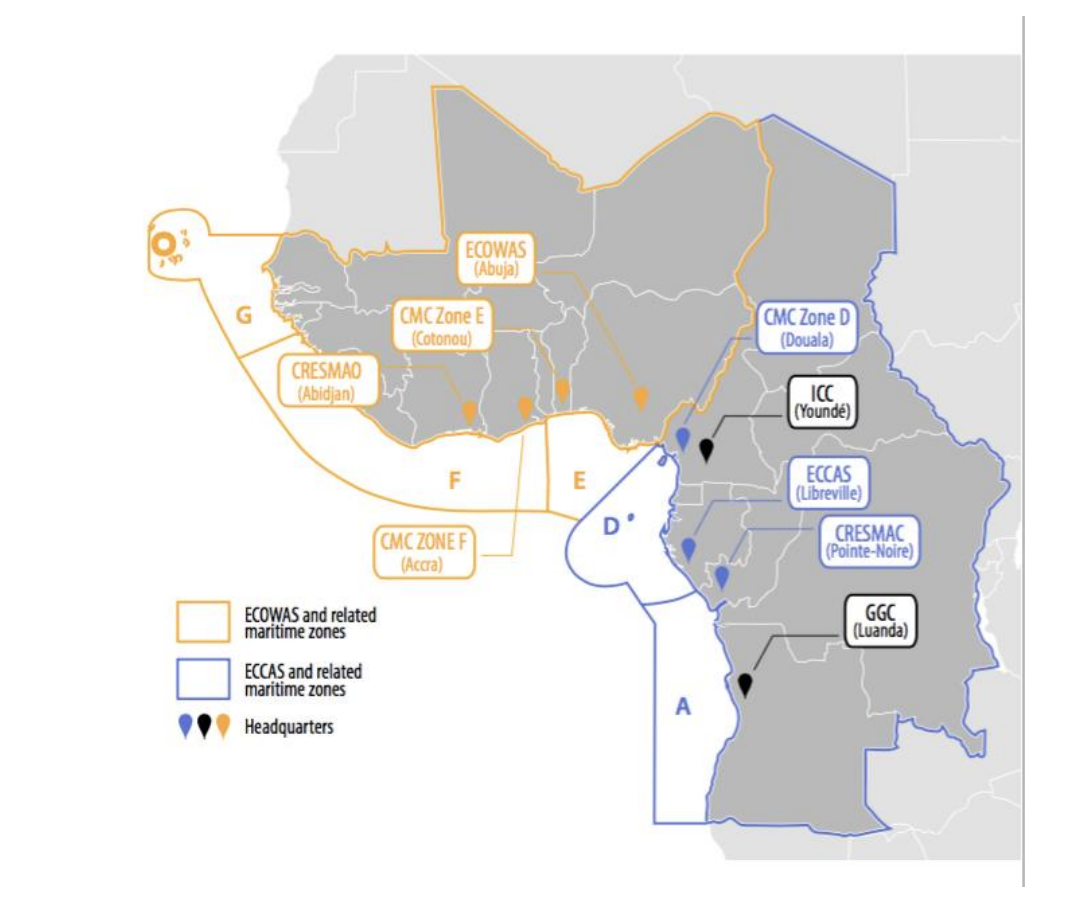

To mitigate the political and strategic uncertainty that can result from low MEC, it is important for regional security institutions to have maritime security strategies in place that broadly delineate responsibilities in the case of maritime VNSA attacks against an operationally-limited country. In these resource-constrained countries, it is also important to incorporate the maritime domain into national counterinsurgency and counterterrorism strategies. This would be a useful mitigative action and allow for a more holistic response to the maritime capabilities of VNSAs, should the need arise.

Conclusion

Taking a more expansive view, Ansar al-Sunna’s most recent campaign serves as a warning for other states with low MEC. Whether or not maritime-capable VNSAs are currently present in a state should not deter states from taking action now. The threat is too real. In a mere five months, Ansar al-Sunna became one of the most active maritime-oriented VNSAs on the African continent, highlighting the importance of closing domestic maritime security gaps. Ultimately, investing in MEC is a holistic mitigative and response measure to the myriad threats posed by VNSAs, one that will reward proactive states best and better position them to successfully counter future threats.

Kelly Moss is an African Maritime Security Researcher at Stable Seas, a program of One Earth Future. Her research and publication background focuses on terrorism and substate violence in sub-Saharan Africa. Kelly graduated from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, where she received her master’s degree in Security Studies, and has worked at three U.S. federal government agencies, including the Bureau of African Affairs at the Department of State.

Featured Image: The sun rises as fishermen seek clams and bait in Pemba, Mozambique, July 12, 2018.(Reuters/Mike Hutchings/File Photo)