Along with the release of the International Maritime Bureau (IMB)’s 2012 piracy report come the onslaught of analysts seeking to explain 1) why the crime is decreasing in certain theaters, 2) why it is expanding in others, and 3) where it will spread next.

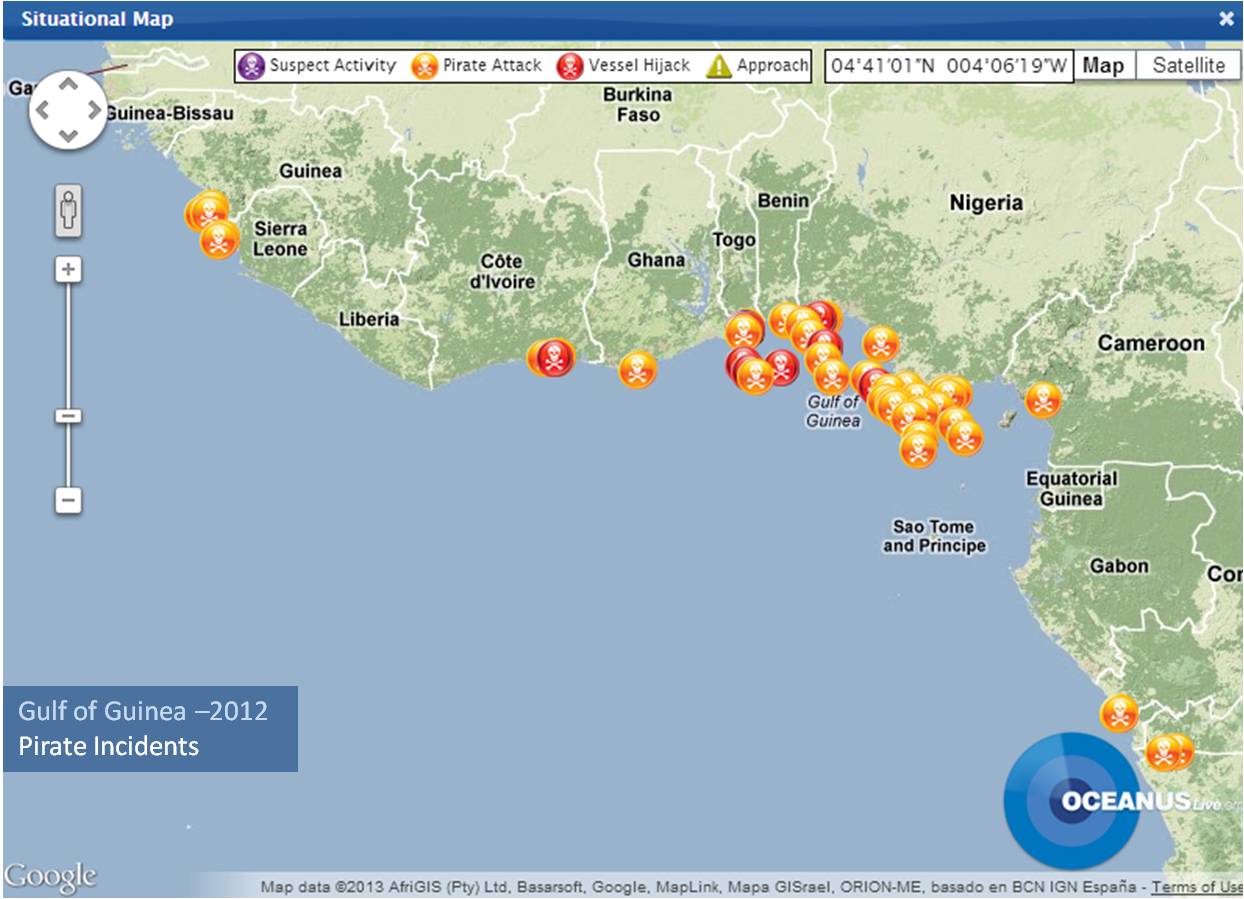

The top story is that global pirate attacks have hit a five-year low, thanks to a sharp decline in the activities of Somalia’s notorious marauders. When this trend is reported it is almost always followed by the caveat that a “new” piracy epicenter has “emerged” in Nigeria and that the criminal enterprise is now increasing and expanding across the Gulf of Guinea. These types of statements are an oversimplification, however, and mask the complexities of maritime crime in West Africa.

Playing with Numbers

A multitude of criminal actors have parasitically operated in the Nigerian littoral since the country’s oil boom in the 1970s—piracy, kidnapping, and oil theft are by no means “new” to the region. To say that the country has “reemerged” as an epicenter of maritime crime is more accurate, as it was only in 2007 that Somali waters became more pirate prone than those of Nigeria. The 27 pirate attacks reported for Nigeria in 2012 represents an increase over the past two years, but fall well short of the 42 attacks the IMB recorded in 2007.

One must also be careful (a mistake this author is willing to admit) about reporting an absolute “increase” in the total number of pirate attacks that have taken place in West Africa over the past year. The IMB’s figures display a clear trend: attacks off Nigeria increased from 10 to 27, while those for the region as a whole rose from 44 to 51. These numbers are incomplete, however, as they only include incidents that were directly reported to the IMB; whereas an estimated 50-80% of pirate attacks go unreported.

The larger data set of the Danish consultancy firm Risk Intelligence reveals a decrease in Nigerian and West African piracy. The company recorded 48 attacks in Nigerian waters in 2012, a higher number than the IMB reported, but lower than Risk Intelligence’s 2011 and 2010 figures, recorded as 52 and 73 attacks respectively. The expansion of pirate gangs into the waters of neighboring states explains why attacks may have decreased in Nigeria, but it is also noted that the total figure for West African waters has fallen from 116 in 2011 to 89 in 2012.

Table 1: Incidents of Piracy off Nigeria and West Africa: 2008-2012 (Risk Intelligence)

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Nigeria | 114 | 91 | 73 | 52 | 48 |

| West Africa Total | 138 | 120 | 110 | 116 | 89 |

| Nigerian Incidents as Percentage of Regional Total | 82.6% | 75.8% | 66.3% | 44.8% | 53.9% |

Not More, but Different

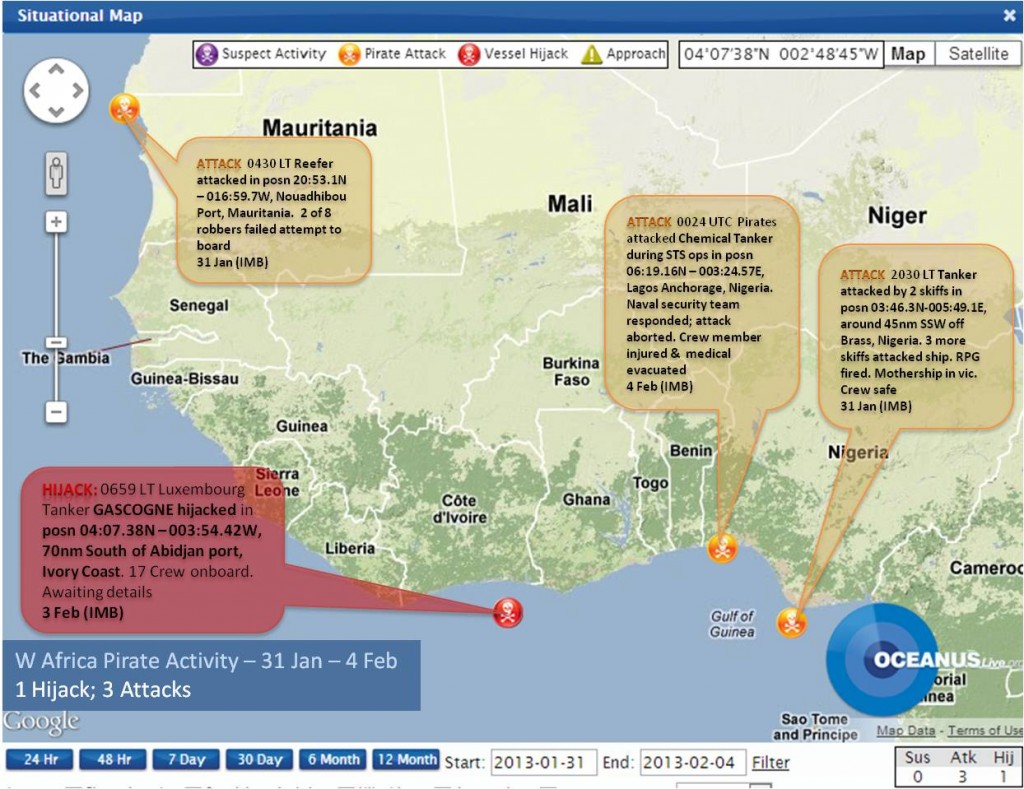

An overall decline in the total number of pirate attacks in the Gulf of Guinea does not mean that the problem is being a solved. The January 16 hijacking of the Panamanian-flagged product tanker Itri and February 4th hijacking of the Luxembourg-flagged tanker MT Gascogne, both off Côte d’Ivoire, attest that the threat remains high, but has shifted in terms of its targets and scope.

The rampant maritime crime and insurgency that plagued Nigeria in the mid-to-late 2000s displayed a mixture of communal, political and economic motives and was frequently directed towards supply vessels and fixed assets operating in oil and gas fields off the Niger Delta. A 2009 amnesty offered by the federal government essentially served to buy off thousands of Delta militants, rewarding some of them with huge security contracts to protect the waters they had previously hunted in. It is this change in the security environment that is credited with the sharp decline in pirate attacks in Nigerian waters seen in Table 1.

Heightened security in the Nigerian littoral appears to have had a Darwinian effect on maritime criminals, as more sophisticated and politically connected syndicates have thrived at the relative expense of opportunistic “smash-and-grab” pirates.

One manner in which this is evident is target selection. Attacks against support vessels operating close to shore have declined over the last five years (and with them, the total number of incidents), but this has coincided, since 2010, with a surge in tanker hijackings. According to the records of one corporate security manager operating in Nigeria, there were 42 attacks against supply vessels in 2008 (one of the worst years of the Niger Delta insurgency), but only 15 in 2012. Conversely, there were just 8 attacks against tankers and cargo ships in 2008, but 42 in 2012. In total, Risk Intelligence has recorded 78 attempted attacks on product tankers and 27 short-duration hijackings since December 2010.

This shift in targets might explain why commenters incorrectly refer to rising levels of piracy in the region, as the hijacking and short-term disappearance of tankers owned by international companies garners far greater media attention than the robbing of supply ships, despite the fact that these types of attacks were more frequent.

Bigger and Better

While boarding a supply vessel and robbing it of valuables is a relatively low-tech affair, hijacking a product tanker and pilfering vast quantities of fuel over several days requires a high degree of organization and sophistication. The confessions of four captured pirates, believed to be behind the hijacking of the Energy Centurion off the coast of Togo on August 28, 2012, reveals the intricacies of such an operation.

According to one testimony, criminal syndicates are “sponsored by powerful people,” including Nigerian government officials and oil industry executives, who provide advanced payment and information about the cargo, route, and security details of ships that have been targeted. These intelligence-led operations have become increasingly multinational with gangs based in Nigeria planning attacks off the coasts of Benin, Togo, and Côte d’Ivoire, often with the assistance of nationals from these countries.

Once a vessel has been hijacked, pirates have been known to go to great lengths to make sure that the ship ‘disappears’ while preparations are made to offload the cargo. For example, the gang that hijacked the product tanker MT Anuket Emerald made sure to damage all the ship’s communication equipment and loading computer, repaint its funnel, change the tanker’s name, and remove its IMO number. The offloading and black market sale of stolen product is equally complex, requiring a network of “oil mafia” insiders who facilitate fuel storage at numerous depots across Nigeria and then organize for onward distribution.

Money over Everything

Though fewer ships are being attacked, the current crop of West African pirates (and their financial backers) are seeing greater returns. The group that recently hijacked the Itri was able to siphon off the ship’s entire cargo of fuel, valued at $5 million. Captured pirates involved in tanker hijackings (dubiously) claim that payoffs range from $17,000 for new recruits to over $60,000 for ‘commanders.’ The value of large-scale oil theft exceeds many of the ransom sums made by Somali pirates and is acquired without months of hostage negotiations. Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, notes piracy expert Martin Murphy, is now “the most lucrative in the world.”

The West African modus operandi is also more secure, as Nigerian pirates are not subjected to the same risks as their Somali counterparts—namely extended voyages in treacherous open ocean, the combined pressure of the world’s greatest navies, and the widespread use of professional armed guards aboard merchant vessels. Endemic corruption in Nigeria assures that even if pirates are caught, they are unlikely to face serious consequences. The Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency and Joint Task Force have made dozens of arrests in recent months, but lack the authority to detain or prosecute suspects as this is the responsibility of other security agencies. Bribes to these agencies, captured pirates note, are set aside as an operational expense, meaning most suspects are released without charge.

In terms of numbers, overall pirate attacks may be declining in the Gulf of Guinea, but the gangs responsible appear to have increased both their operational sophistication and target selectivity. Given the increased value of each operation and the small risk of punishment their crimes show no signs of disappearing.

James M. Bridger is a Maritime Security Consultant and piracy specialist with Delex Systems Inc. He can be reached at jbridger@delex.com