By Andrew Song

How does one find an object not meant to be found? Forensic maritime investigators in 2017 stumbled across this question when searching for the disappeared ARA San Juan (S-42) – an Argentinian submarine whose mission centered around stealth. Despite the environmental challenges and the restrictions imposed by the profile of submarines, several complementary forensic tools have emerged as authoritative standards and best practices for underwater search operations. These include: (1) optimization of preliminary search boxes through Bayesian probabilities, with updates for posterior probabilities throughout the search; (2) side-scanning sonar systems; and (3) unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) for imagery, access, and identity verification. In explaining the efficacies and drawbacks of such methods, this analysis highlights the importance and evolving future of search optimization strategies.

How to Find a Lost Submarine

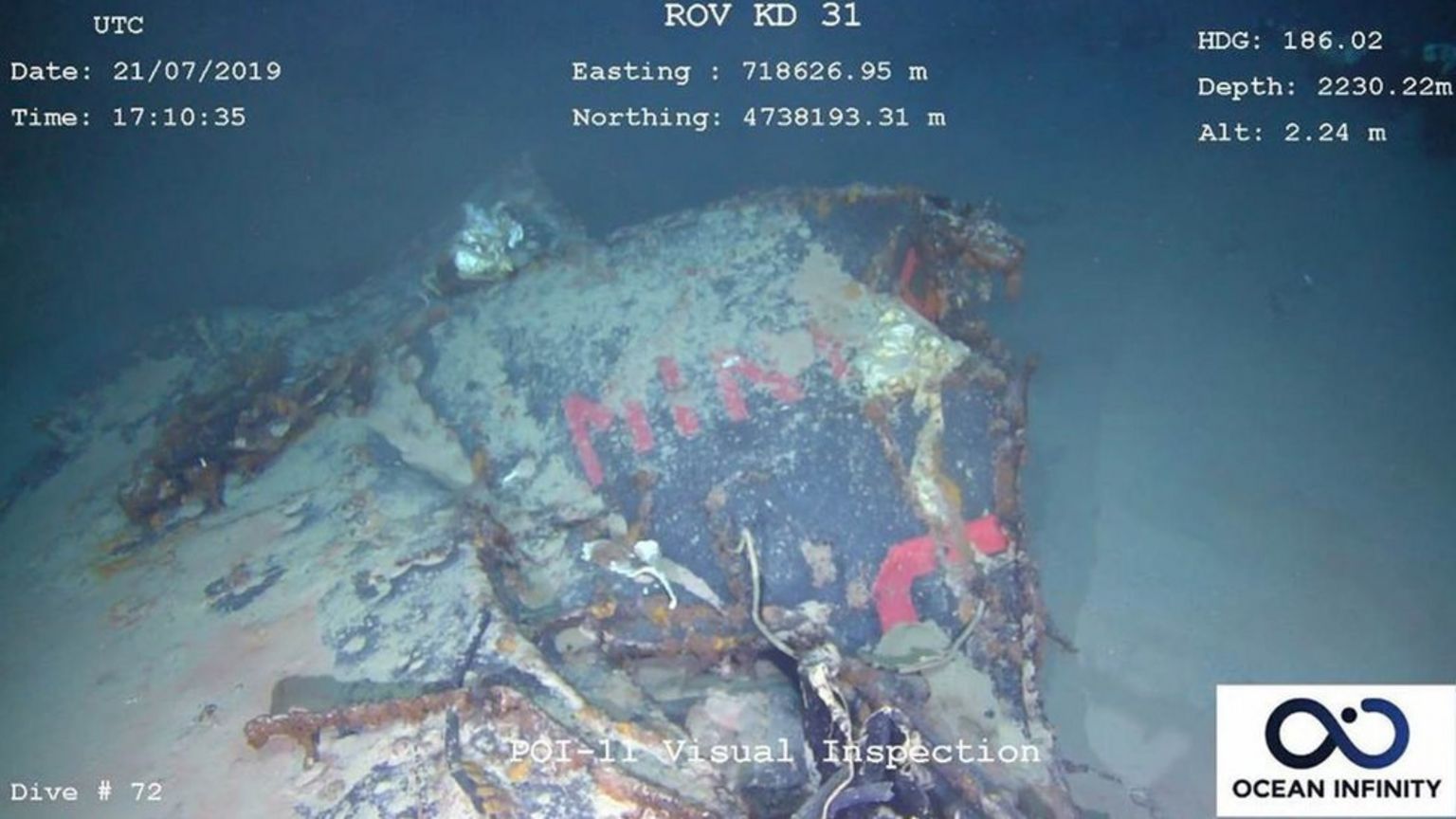

Forensic maritime investigators confront distinct challenges not relevant for traditional land-based investigations. Unlike terrestrial-based forensics, pre-established knowledge of a local maritime environment is sparse. Scientists have mapped 1/5th of the sea floor to modern standards with 100m resolution, but that means almost 290 million square kilometers of seafloor—twice the surface area of Mars—have not yet been surveyed.1 Furthermore, the remoteness of submarine operational areas casts a wide speculative net for a submarine’s last location, acting as a red herring for planners. For instance, the French Navy finally found the Minerve in July 2019 after searching since 1968, but the submarine’s position was only 28 miles off the coast of Toulouse.2

The absence of existing charts, therefore, necessitates simultaneous 4-D mapping of the area—which is in short supply. Submarine debris is unidentifiable in satellite and aerial images due to surface opacity and the extreme depth of wreckages. Stratification conceals wreckage and clearing sedimentary buildup becomes extremely complicated due to sheer volume. An onsite “walk-over” survey, as described by Fenning and Donnelly3 in their description of geophysical methodologies, is simply impossible in a marine environment. Acidity and pH levels of the water also influence rates of decomposition, and must be considered for a simulation in the casualty scenario.

1: Bayesian Search Strategies

Constructing a preliminary search box requires meticulous strategizing and calculations. An error associated with misanalysis of primary sources can inevitably mislead search and rescue planners, delaying a submarine’s discovery. This occurred in the case of the USS Grayback, as Navy officials mistranslated the final coordinates of the submarine documented by a Japanese carrier-based bomber.4 An incorrectly interpreted digit in the longitudinal coordinates created an erroneous search area straying 160 kilometers from the Grayback’s actual location.5

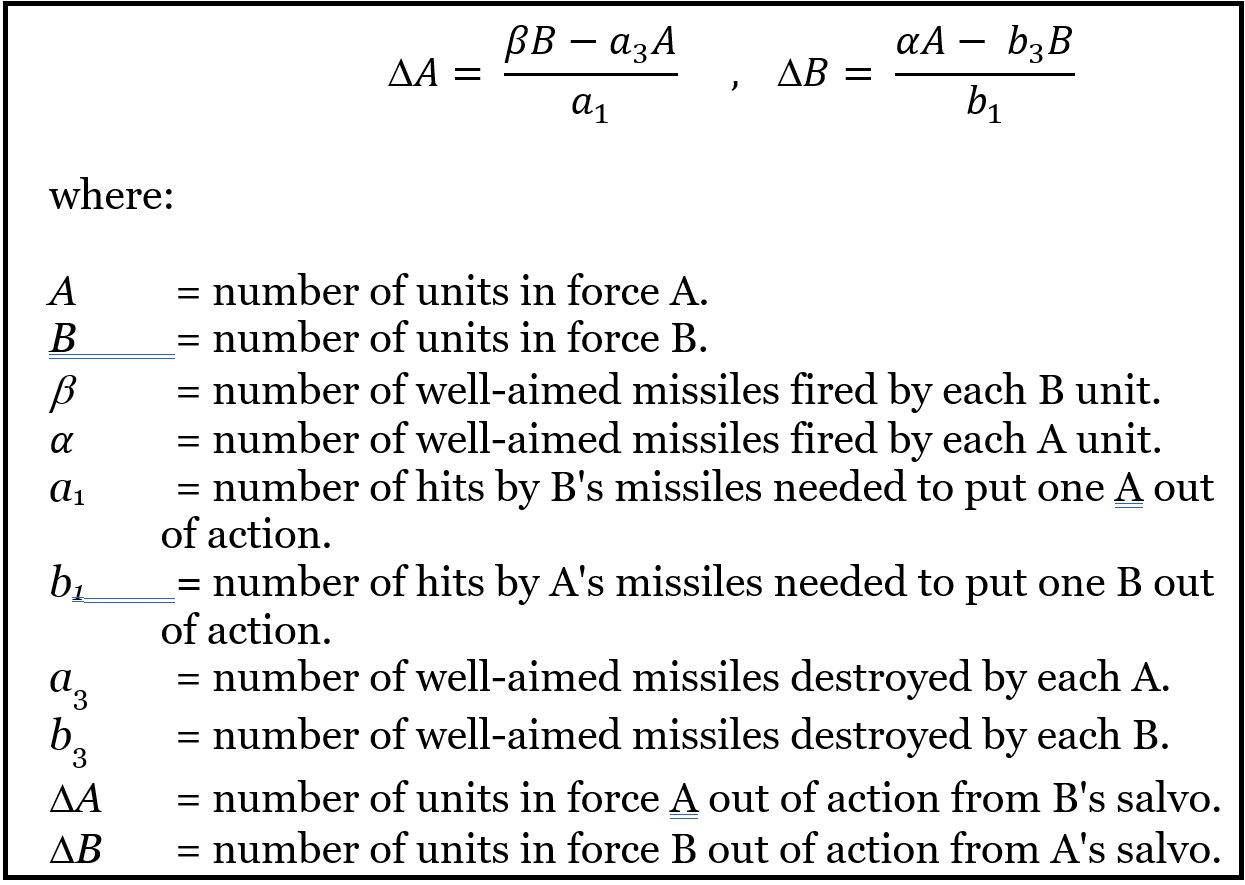

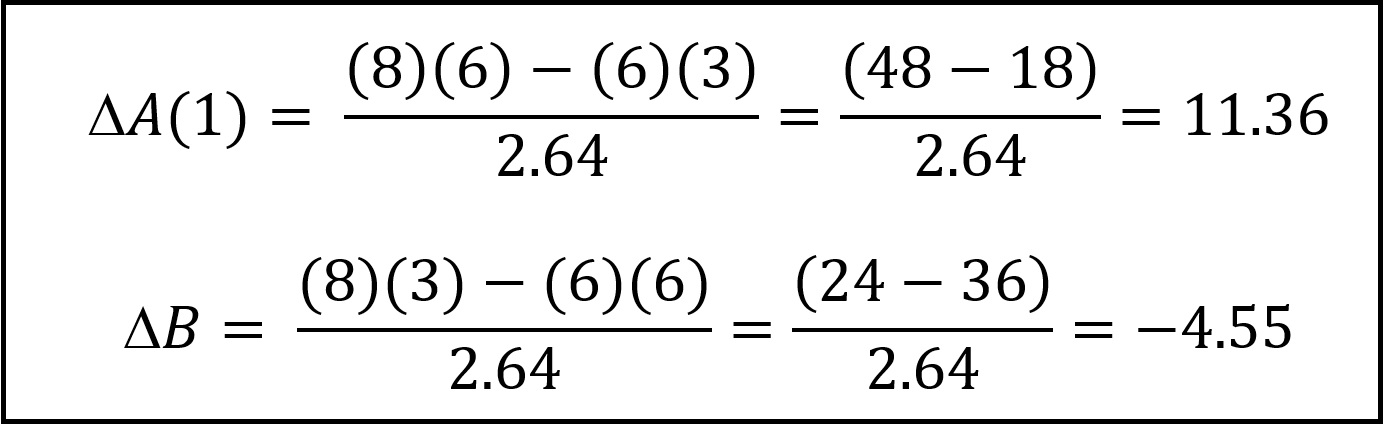

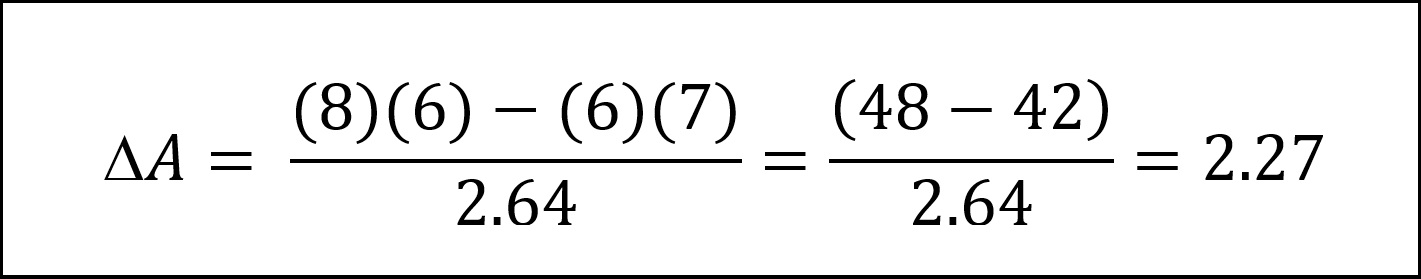

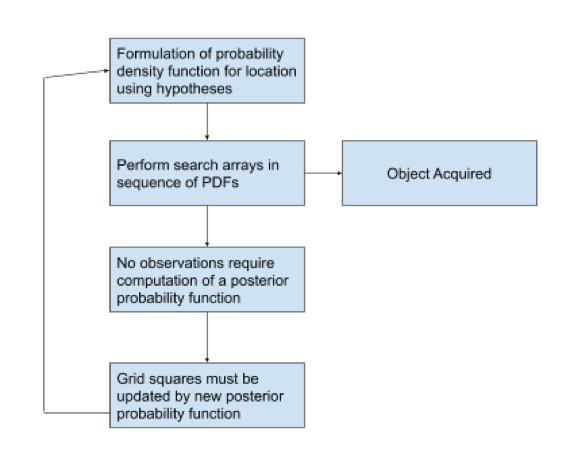

Pitfalls in relying on a single source cause planners to use search strategies based on Bayesian statistics. At a rudimentary level, Bayes’ theorem leverages probabilities of an event and prior knowledge regarding the condition of such event to produce a reasonable prediction of an event’s occurrence. Stakeholders will first formulate a range of possible stories surrounding a missing submarine’s location, pulling from all potential sources (eyewitness testimony of submarine’s last submergence, operational logs, mission record, etc.). The credibility and value of each piece of evidence will be judged by investigators and experts who will then collectively assign statistical weight to possible scenarios. For instance, the USS Scorpion’s forensic team invited experienced submarine commanders to present reasonable hypotheses that the scientists would later input into a probability density function.6 Such probability density functions assist planners in prioritizing certain search zones for surveying. Investigators resort to Bayesian statistics and Bayesian inference models because of its predictive power and the comprehensive results derived from relatively few inputs. Figure A demonstrates a four-step hierarchical convention in a Bayesian search strategy. The diagram summarizes the effects of updates on the model and introduces the posterior probability function (PPF).

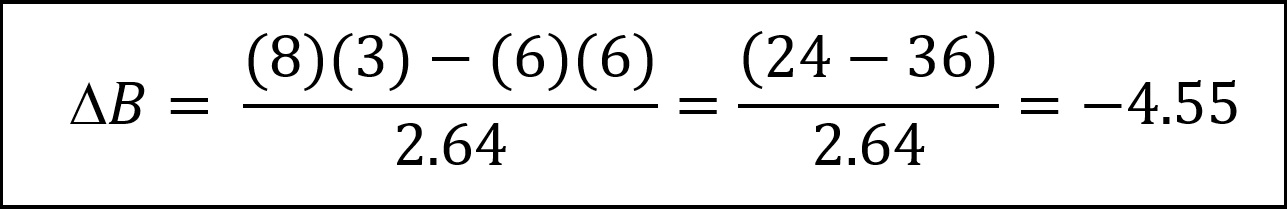

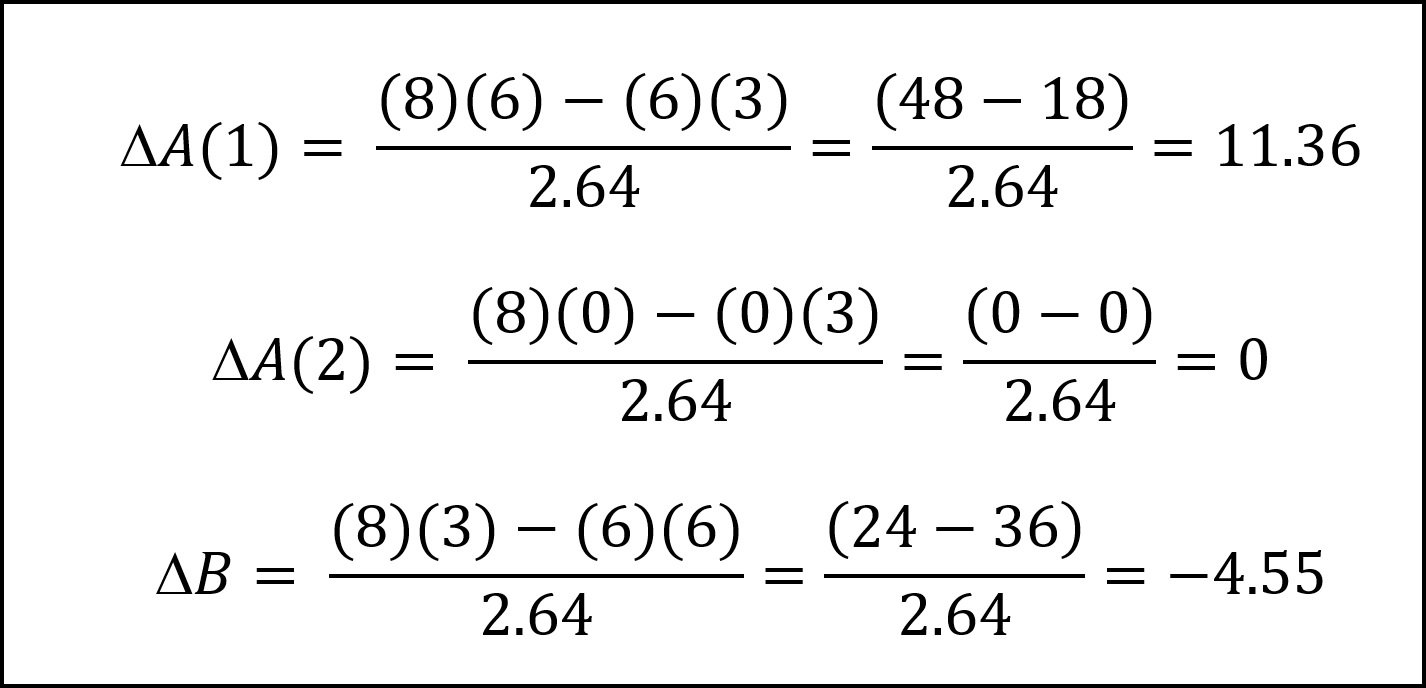

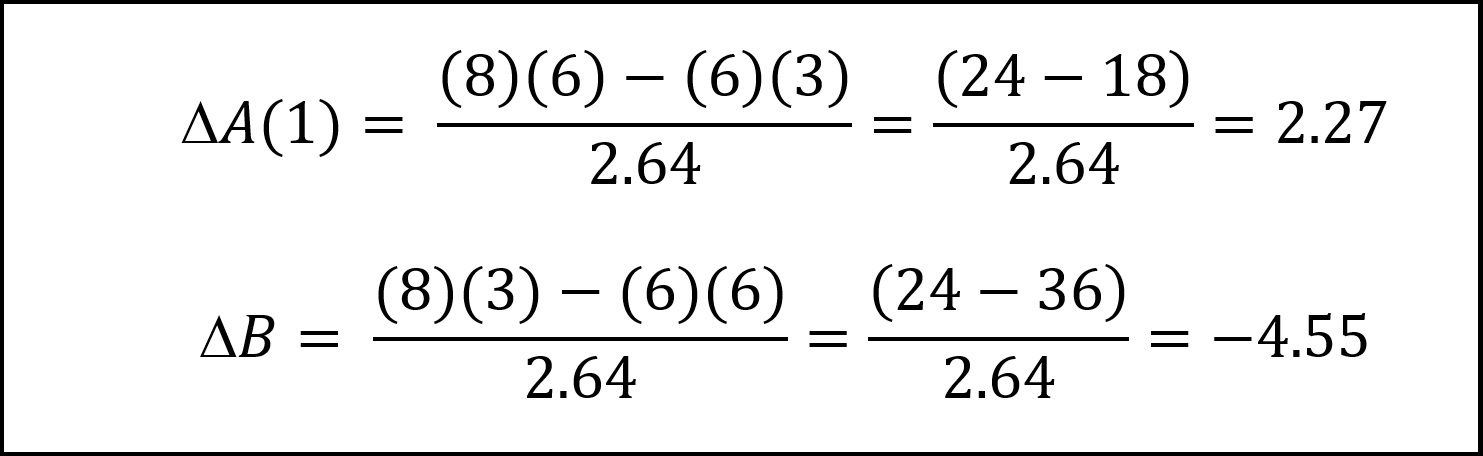

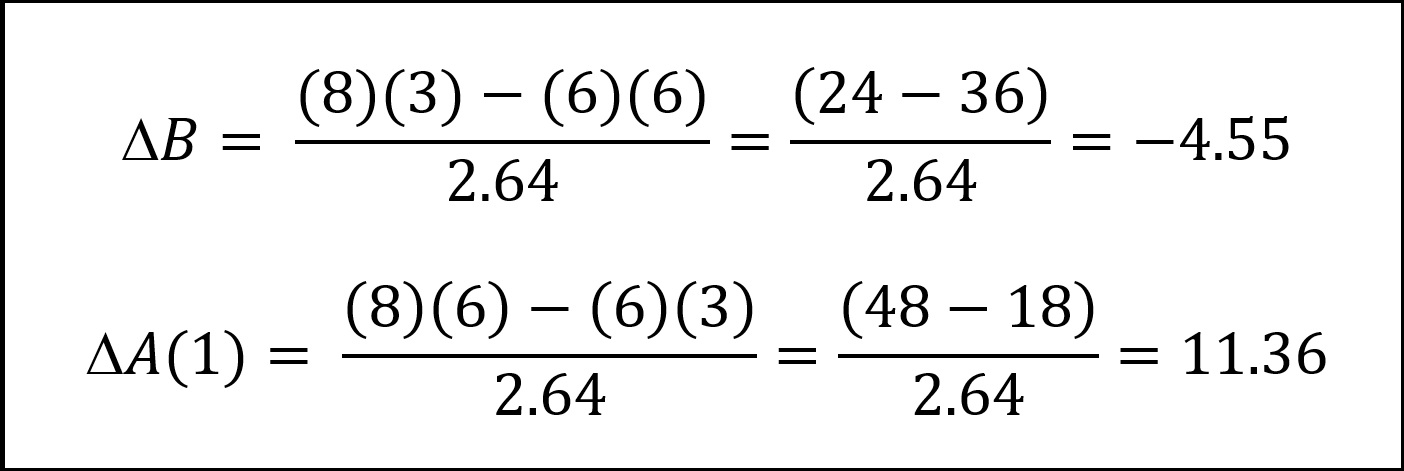

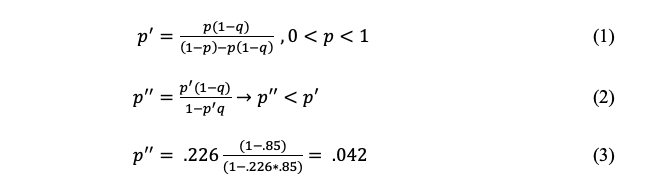

When a search area fails to yield any evidence pointing to a submarine, a posterior probability function will be calculated. A PPF’s utility and role is best explained by Equation (1-2)’s hypothetical representation of a grid square’s probability of containing a submarine. Variable q represents the probability of successful detection of a wreck and p quantifies the probability that the grid square does contain the wreck. Failing to find a wreck in a grid square will revise the probability of that grid square into p prime—a posterior probability.7 In this theoretical situation, the probabilities (for purely illustrative purposes) are: that a wreck in the grid square is 67% and the chances of a side-scan sonar identifying an anomaly is 85%.

Under those numeric assumptions, if the submarine were not found in the first survey, then a second survey of the same grid square, as denoted in Equation (3), will yield a secondary posterior probability of approximately 4.2%. Taken together, 4.2% represents the chances of success in finding the submarine in the given grid square in a second sweep.

Bayesian strategies are a staple of operations analysis search theory. For instance, the U.S Coast Guard incorporates Bayesian search strategies into its Search and Rescue Optimal Planning System (SAROPS).8 Successful outcomes produced by Bayesian search strategies have led to a general consensus on the technique’s utility. Identification of the underwater wreckage site of Air France Flight AF 477 underscored this utility. In the 2011 discovery, investigators created probability density functions (PDFs) from weighted scenarios supplemented by anterior knowledge of nine commercial aircraft accidents, known flight dynamics, and final trajectories.9 These PDFs drew search boxes that broadened until a Brazilian corvette recovered components of AF 477 buoyed on the surface.

However, Bayesian search strategies warrant legitimate criticism for their implicit use of subjective analysis. Terrill and Project Discover’s usage of Bayesian search strategies narrates a story of arbitrary values associated with each scenario. This is seen especially when the researchers place heavy subjective weight on interview data from the few remaining witnesses of a B-24 bomber’s last location.10 Taken together, Bayesian search strategies force analysts to quantify what is essentially qualitative information (e.g., the probability that an elderly man can accurately recall the events of the crash). These limitations create possibilities for higher uncertainty and a wider confidence interval. In addition, Bayesian search strategy can overshadow other powerful methods to form search boxes such as a Gittins index formula.11

2: Implementation of Side-Scanning Sonar for Seabed Imaging

Sonar, otherwise known as sound navigation and ranging, is a method that leverages sound propagation as a way to detect an object’s position and to visualize shapes from acoustic signatures in the form of echoes. The return frequency and radiated noise of an object allow for target acquisition and safe navigation by submarines dependent on the vicinity’s sound velocity profile; for researchers hoping to find inactive submarines, side-scan sonars lend mapping capabilities.

These devices construct images from cross-track slices supplied by continuous conical acoustic beams that reflect from the seafloor—wave emission speed can reach nearly 512 discrete sonar beams at a rate of 40 times a second.12 Data produced by side-scan sonars assembles a sonogram that converts into a digital form for visualization. The utility of side scan sonars is trinitarian; they create effective working images of swaths of sea floor when used in conjunction with bathymetric soundings and sub-bottom profiler data.13 Form factors of side-scan sonars allow the device to be highly mobile and serve as flexible, towable attachments for the tail of any-sized ships, giving liberty to human operators to adjust the directionality of ensonification. In addition, side-scan sonars contain adjustable frequency settings. A change in a side-scan sonar’s frequency will affect the sonar’s emitting wavelength, giving the operator flexibility on target acquisition. Side-scan sonars can operate as low as the 50kHz range to cover maximum seabed area; alternatively, the instrument can operate at 1 MHz for maximum resolution. This feature is extremely vital because submarines alter in length by model and different bodies of water share unique sound velocity profiles. Another advantage with side-scan sonars is their high precision record at sub-meter accuracy level for horizontal planes and at the centimeter-error level for vertical planes.14

Side-scan sonar systems exist as a vital apparatus to any search operation because the alternatives for mapping are minimal. Methods other than side-scan sonars like low-frequency multi-beam bathymetric data scanners, when reappropriated, are imperfect in object identification accuracy and better for scanning large seabed topographic structures like underwater mountains.15 Recent advances in magnetic anomaly detectors16 appear promising for future seabed exploration, but these instruments still require parallel approaches or in-tandem usage with side-scan sonars. Until magnetometers can extend their range beyond identifying magnetic objects in the Epipelagic Zone—the uppermost layer of the ocean where sunlight is still available for photosynthesis—side-scan sonars will be more consistent and versatile than magnetometers.

Deployment of side-scan sonar occurs in the intermediary stage of search operations. A vessel will have a side-scan sonar mounted on or embedded in a towfish. Tethered to the main vessel, the side-scan sonar will perform a proper sonar survey of a proposed area by maintaining a rigid survey line along with a consistent towfish “altitude” when trailing the ship. Technicians carefully check the GPS receiver of the towfish to rectify course deviations, if needed, by manually changing the ship and towfish’s heading. A side-scan sonar operates with a survey mode to capture anomalies, which visual graphs will register and mark for later investigation by an unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV).

Unfortunately, handlers of side-scan sonars will notice several limitations that must be accommodated. A restriction to side-scan sonars is their inability to image directly below side-scan transducers. In other words, ships must compensate for a side-scanner’s blind spot by staggering their mow-the-lawn strategy. In addition, side-scan sonars contain software that prohibits the surpassing of a certain speed limit for towing, lest the receiver show significant scattering, absorption, and incoherent imagery. Like other instruments, side-scan sonars’ physical power consumption can be a variable for constraint.

Lastly, side-scan sonars perform according to the quality of the bathymetric data supplied. By themselves, side-scan sonars cannot efficiently identify changes in gradients and sound velocity profiles in real-time. High frequency/high resolution sonars operate at relatively short ranges via direct path sound propagation, which limits the refraction of sound waves and consequent distortion. This means the side-scan sonar will have a handicap in reporting the propagation paths of its rays and the sound channels, meaning knowledge of shadow zones may be omitted.17 This is a search investigator’s worst nightmare because failure to adequately search a grid may lead to incorrect, permanent marking of a square not holding a target. Imperfect data or simply lack of bathymetry data also contribute to the limitation of side-scan sonars.

3: Integration of Adaptive Unmanned Underwater Vehicles for Forensic Searches.

Since their introduction in the 1960s, UUVs have played a major role in every forensic investigation for a lost submarine. UUVs act as surrogates to human divers who cannot comfortably operate for extended periods of time at depths greater than 100 meters. To illustrate the need for UUVs, the USS Grayback was discovered at a depth of 1,417 feet (431 meters)18 — an impossible depth for divers, but not for the submarine itself. UUVs support forensic scientists in more than just underwater photography. UUVs collect bathymetry data, use ultrasonic imaging, measure strength of ocean currents, and detect foreign objects by their inertial or magnetic properties. Variants of UUVs are categorized into two robotic classes: remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). ROVs allow for direct piloting by a human operator from a remote location with signal. AUVs function independently and follow pre-programmed behavioral search patterns.

The UUV variant, Remus 100,19 manufactured by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, deceptively resembles a torpedo, but functions as an effective explosive ordnance disposal detection device for the Navy. When refitted for search operations, the Remus (AUV) variant can perform dual-frequency side-scan sonar operations in independent mow-the-lawn search sequences.20 The Remus’ transponder wields GPS and doppler velocity logs that have proven to be more accurate in measurements than earlier AUVs. Customarily, forensic actors will deploy ROVs and AUVs for close-up identification or routine investigation of an anomaly, instead of wide-area search missions. These ROVs display high-definition, colorized video feeds for operators on a vessel; the latency between pilots and the ROV ranges from one to two seconds, making for fast time on responsive decisions.

Conclusion

This analysis examines a trinity of contemporary methods revolving around statistics and autonomous vehicles that aid officials in search and rescue operations for submarines. Corporations and officials should note that innovating and constructing more effective models in search operation becomes worthwhile when speed determines the ability to save lives. While this analysis discusses the employment of the aforementioned technology in the context of submarines, these methods can be theoretically implemented for other maritime interests: finding missing planes, undertaking the historical preservation of shipwreck sites, and embarking on deep-sea mining. For all these reasons, the U.S. has an inherent stake in advancing a discussion about progress in submarine search and rescue tactics.

Andrew Song is a U.S. Navy Nuclear Submarine Officer. His previous publications have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The National Interest, Military Review, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, and Proceedings. He graduated with a B.A. in Global Affairs from Yale University in 2022.

References

1 Amos, Jonathan. “One-Fifth of Earth’s Ocean Floor Is Now Mapped.” BBC News. BBC, June 20, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-53119686.

2 “DOS Involved in the Finding of the French Submarine La Minerve.” Deep Ocean Search, October 3, 2019. http://www.deepoceansearch.com/2019/10/03/dos-involved-in-the-finding-of-the-french-submarine-la-minerve/.

3 Fenning, P. J., Donnelly, L. J., 2004. Geophysical techniques for forensic investigation. Geological Society of London Special Publications, 232, 11-20.

4 Elfrink, Tim. “A WWII Submarine Went Missing for 75 Years. High-Tech Undersea Drones Solved the Mystery.” The Washington Post. WP Company, November 11, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/11/11/uss-grayback-discovered-tim-taylor-lost-project/.

5 Ibid.

6 L.D. Stone, “Operations Analysis during the Underwater Search for Scorpion” Naval Research Logistics Quarterly, vol. 18(2), pp. 141–157. 1971

7 Terrill, E., Moline, M., Scannon, P., Gallimore, E., Shramek, T., Nager, A., Anderson, M. (2017). Project Recover: Extending the Applications of Unmanned Platforms and Autonomy to Support Underwater MIA Searches. Oceanography, 30(2), 150-159. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26201864

8 Stone, L. (2011). Operations Research Helps Locate the Underwater Wreckage of Air France Flight AF 447. Phalanx, 44(4), 21-27. Retrieved March 2, 2021, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24910970

9 Soza & Company, Ltd. (1996). The Theory of Search: A Simplified Explanation: U.S. Coast Guard. Contract Number: DTCG23-95-D-HMS026. Retrieved on 2010-07-18 from http://cgauxsurfaceops.us/documents/TheTheoryofSearch.pdf

10 Terrill, E. “Project Recover.” Oceanography 2017.

11 Weitzman, Martin L. (1979). “Optimal Search for the Best Alternative”. Econometrica. 47 (3): 641–654.

12 “Side Scan Sonar.” Exploration Tools: Side Scan Sonar: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2002. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/technology/sonar/side-scan.html.

13 Jean M. Audibert, Jun Huang. Chapter 16 Geophysical and Geotechnical Design, Handbook of Offshore Engineering, Elsevier, 2005. ISBN 9780080443812, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044381-2.50023-0.

14 Aaron Micallef. Chapter 13: Marine Geomorphology: Geomorphological Mapping and the Study of Submarine Landslides, Development in Earth Surface Processes, Elsevier, Vol 15, 2011, pg 377-395 ISBN 9780444534460, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53446-0.00013-6 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444534460000136)

15 Elfrink, “A WWII Submarine went Missing” The Washington Post. 2019.

16 Geophysical Surveying Using Magnetics Methods, January 16, 2004, University of Calgary https://web.archive.org/web/20050310171755/http://www.geo.ucalgary.ca/~wu/Goph547/CSM_MagNotes.pdf

17 “Side Scan Sonar.” United States Naval Academy , February 1, 2018. https://www.usna.edu/Users/oceano/pguth/md_help/geology_course/side_scan_sonar.htm. (2) Sonar Propagation. Department of Defense . Accessed April 7, 2021. https://fas.org/man/dod-101/navy/docs/es310/SNR_PROP/snr_prop.htm.

18 Elfrink, “A WWII Submarine went Missing” The Washington Post. 2019.

19 REMUS”. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. https://www.whoi.edu/what-we-do/explore/underwater-vehicles/auvs/remus/

20 J. Ousingsawat and M. G. Earl, “Modified Lawn-Mower Search Pattern for Areas Comprised of Weighted Regions,” 2007 American Control Conference, New York, NY, USA, 2007, pp. 918-923, doi: 10.1109/ACC.2007.4282850.

Featured Image: August 1986 – A view of the detached sail of the nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Scorpion (SSN-589) laying on the ocean floor. The starboard fairwater plane is visible protruding from the sail. Masts are visible extending from the top of the sail (located at the lower portion of the photograph). A large segment of the after section of the sail, including the deck access hatch, is missing. (Official U.S. Navy photograph)