By Bryan Clark

Regaining the Maritime “High Ground”

Aircraft carriers have been the centerpiece of the U.S. Navy since they came to prominence during the Second World War. Their mobility and firepower were essential to winning the Pacific Campaign during that conflict, and carriers’ adaptability enabled them to remain the fleet’s primary means of power projection through the Cold War and in multiple smaller conflicts thereafter. Unless the Navy dramatically transforms its carrier air wings (CVW), however, the carrier’s preeminence will soon come to an end.

America’s carriers, often the target of adversaries, are once again under threat. China and Russia are investing in networks of sensors and weapons designed to deter U.S. and allied forces from intervening in their regions. As part of their efforts, these great power competitors, in addition to regional powers like Iran and North Korea, are fielding anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles, warships, and submarines to threaten U.S. carriers.

The Navy is developing ways to counter enemy kill chains from initial detection through engagement. Carrier strike groups (CSG) will need to maneuver, minimize their radiofrequency emissions, and limit flight operations to reduce the vulnerability of carriers to detection and targeting and maximize the capacity of their air defenses. But employing these capabilities and tactics could significantly constrain carriers’ sortie generation capacity.

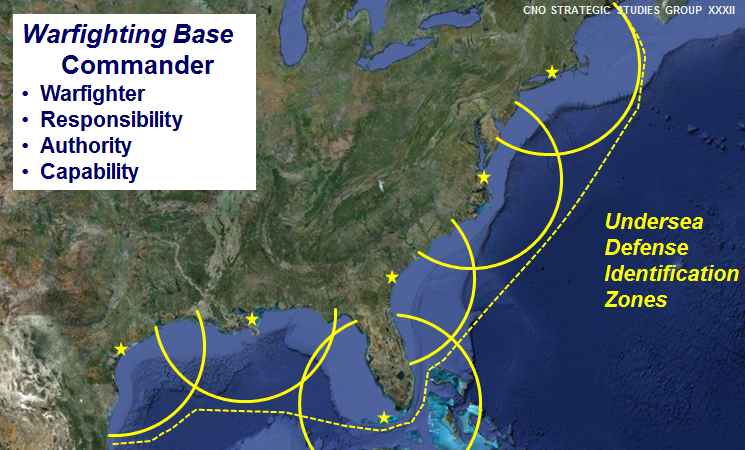

To retain their ability to defeat aggression, CSGs will need to conduct wartime operations from areas where they can generate high-volume sorties and fires and their defenses can realistically defeat enemy attacks. This will likely place them about 1000 miles from concentrations of Russian or Chinese forces, or up to 500 miles from the missile batteries of regional powers. At these ranges, the Navy’ current and planned air defense capabilities will be sufficient for CSGs to protect themselves without having to rely extensively on countering enemy sensors.

Unfortunately, the Navy’s current and planned carrier air wings (CVW) lack the reach, survivability, and specialized capabilities to effectively protect U.S. forces at sea and ashore or attack the enemy from 1000 miles away. Carriers are an important, and in some scenarios essential, element of the National Defense Strategy’s “contact” and “blunt” forces that will counter enemy aggression because they are more heavily defended and less vulnerable than forward land bases. If CSGs cannot substantially contribute to degrading, delaying, or defeating aggression, the Navy should reconsider continuing its investment in carriers and their aircraft and shift those resources toward more effective approaches.

As arguably the ultimate modular military platform, carriers can address emerging threats and opportunities by changing the size and mix of aircraft they carry. Without the ability to evolve and support new missions, carriers and their CVWs would likely have gone the way of the battleship and left the fleet decades ago. Our new Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments study describes how the Navy could transform its CVWs during the next 20 years to address the challenges posed by great power militaries.

Changing Carrier Strategy and Tactics

Some analysts recommend that rather than invest in new aircraft and improved carrier defenses, the Navy should use missiles from surface combatants and submarines to defend naval forces and attack enemy targets. This approach, however, would be unsustainable and may not deter a committed aggressor.

Long-range surface-launched missiles are more expensive and less numerous than the glide, gravity, and powered weapons carried by aircraft. Moreover, once a ship or submarine expends its missiles, it will need to withdraw from the fight to safely reload, even if that reloading could be done at sea. Using large numbers of missile-carrying merchant vessels to sustain fires would not solve these problems, because large numbers of expensive standoff weapons would still be needed, as well as defenses for the vessels carrying them.

Instead of replacing carriers with missiles, the Navy should use them as complementary capabilities. Missile-centric platforms such as submarines and surface combatants are well-suited for the NDS’ contact forces, which will be the first to engage the enemy and need to generate large volumes of offensive and defensive fires on short notice. Carriers should be used mostly in the NDS’ blunt force, which will reinforce and support the contact force. Carriers take time to generate sorties, but can sustain fires as long as the carrier is resupplied, allowing contact force ships and submarines to withdraw and reload. Without the threat of sustained resistance from the blunt force, an aggressor like China could choose to fight through ship-launched missiles until ships and submarines need to reload.

Under this construct, CSGs will be employed in four main categories of operations, which are similar to how carriers were used in previous great power competitions and conflicts:

- Day-to-day training, port calls, and exercises inside contested regions during peacetime to build alliances and demonstrate U.S resolve not to cede waters to adversary intimidation or coercion.

- Smaller-scale operations at long range against highly defended targets of great power adversaries, such as strike and surface warfare (SUW) attacks of 200 weapons or less, electromagnetic warfare (EMW) or escort missions, and anti-submarine warfare (ASW);

- Sustained operations at the periphery of great power confrontations, such as in the Philippine or South China Seas against China or in the Norwegian Sea against Russia; and

- The full range of operations against regional powers such as Iran or North Korea that lack integrated, long-range surveillance, anti-air, and anti-ship capabilities.

Within these broad categories, CVWs will need perform the same missions they do today, but using new operational concepts that address ongoing and future enhancements to adversary threats and the geographic advantages enjoyed by great power and some regional adversaries.

The predominant challenge facing U.S. forces against China and Russia is the threat of long-range precision weapons, making air and missile defense an important enabling concept for CVWs. To survive against Chinese or Russian surface-, air-, and submarine-launched missiles, U.S. forces will need to complement air defenses on ships and air bases with actions to thin out missile salvos in flight and attack enemy missile-launching “archers” before they can launch their “arrows.”

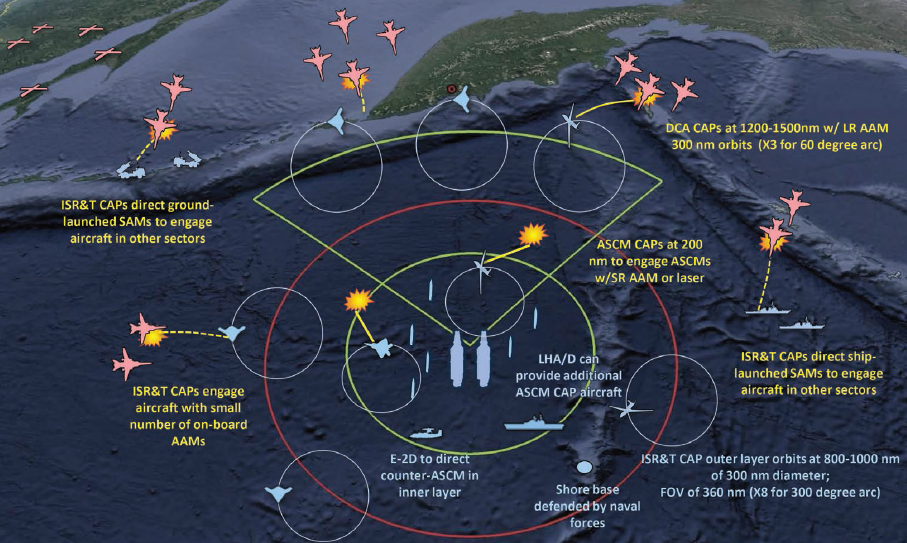

This updated version of the Navy’s “Outer Air Battle” doctrine would place defensive counterair (DCA) combat air patrols (CAP) along the most likely threat axes at the ranges of future anti-ship and land-attack missiles, or about 800 to 1,000 miles. Outside the most likely threat sectors, distributed fires from surface combatants, ground-based air defenses, and DCA aircraft would engage enemy aircraft using targeting from intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISR&T) CAPs. Shorter-range CAPs operating 100-200 miles from carriers and other defended targets would thin out cruise missile salvos, effectively adding capacity to ship and shore-based air defenses.

Because of their operating areas and the challenge of air- and sea-launched missiles, future CVW strike and SUW operations will need to occur 500–1,000 miles away from the CSG, depending on the adversary. Using standoff weapons such as the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) could allow carrier aircraft to launch strike and SUW attacks from closer to the carrier, but these weapons are expensive and in short supply. Instead, strike and SUW operations will need to occur from shorter standoff ranges, employing a combination of survivable aircraft, and offensive counterair (OCA) and EMW operations.

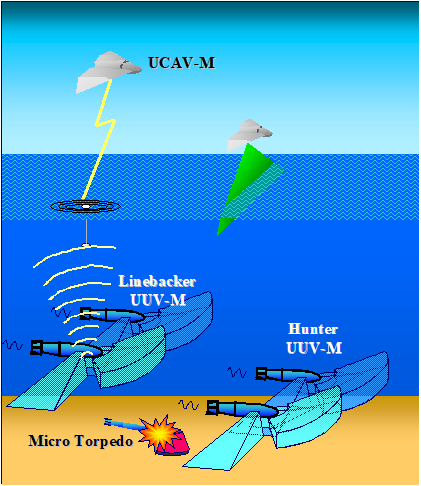

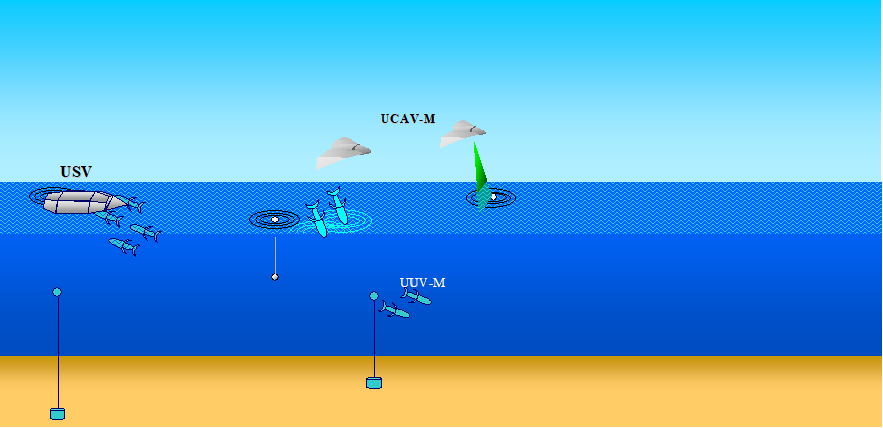

With the growing number and sophistication of Russian and Chinese submarines, the Navy has reinvigorated its efforts at anti-submarine warfare (ASW). Today’s ASW platforms such as the P-8A Poseidon are potentially too vulnerable to conduct ASW operations near a great power adversary’s territory. Others, like the MH-60R Seahawk helicopter, lack the range or endurance to conduct ASW operations beyond the 1,000-mile reach of enemy submarine-launched cruise missiles. To conduct ASW in contested areas, U.S. naval forces will need to rely increasingly on unmanned sensors to find and target submarines. CVW aircraft operating in ASW CAPs would then promptly engage possible submarines at ranges of up to 1,000 miles from the carrier or defended areas ashore.

U.S. adversaries are likely to protect valuable ports, airfields, and sensor and C2 facilities with their own DCA CAPs and air defense systems. To enable CVW or land-based attack aircraft to closely approach targets and use smaller short-range weapons, carrier-based escort aircraft could attack air defenses, help protect strike aircraft from CAPs, and launch expendable jammers and decoys to confuse aircraft and air defense radars and weapons.

Escort missions will require a combination of long-range fighters able to engage enemy DCA CAPs and attack aircraft with the payload capacity to carry missile- or unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-borne jammers, sensors, or decoys. An attack aircraft could also carry high-power standoff jammers such as the Next Generation Jammer (NGJ) that will be carried by the E/A-18G Growler until it retires in the 2030s.

A Needed Transformation

The operational concepts needed to implement current and likely future defense strategies will require new aircraft and a different CVW configuration than in today’s fleet. CSBA’s proposed CVW would include:

Long-range Multi-mission Survivable Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle (UCAV)

Air and missile defense, ISR&T, strike, SUW, ASW, and EMW missions are all evolving in a way that makes them best conducted by aircraft with longer range or endurance, higher survivability, and a payload on par with today’s Navy strike-fighters. An attack aircraft such as an unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) could achieve an unrefueled range of up to 3,000 miles through a fuel-efficient airframe optimized for subsonic speeds. A UCAV could also achieve high levels of survivability by combining a radar-scattering shape with electronic warfare systems and self-defense weapons. And although being unmanned would not necessarily increase its range, a UCAV would be capable of longer endurance than manned strike-fighters provided aerial refueling is available.

UCAV-based Airborne Electronic Attack (AEA) Aircraft

The Navy plans to continue using the E/A-18G as its AEA platform into the 2030s and beyond, but its reliance on standoff effects from outside the range of enemy air defenses is likely unsustainable in the face of improving passive sensors and the increasing range of surface-to-air missiles (SAM) and AAMs. A low-observable platform such as the proposed UCAV could be made into an stand-in AEA platform by incorporating subsystems of the E/A-18G into its mission bay and installing multiple active electronically scanned arrays (AESA) along its wings and fuselage. A UCAV-based AEA aircraft could also carry and deploy expendable EMW UAVs and missiles that would conduct ISR&T, jamming, decoy, and deception operations over target areas.

Unmanned Aerial Refueling Aircraft (MQ-25)

A dedicated carrier-based aerial refueling tanker could enable CVW aircraft to reach CAP stations 1,000 miles from the carrier and conduct long-range attacks against enemy ships and shore targets. The U.S. Navy is already pursuing the MQ-25 carrier-based tanker UAV for this reason and recently awarded design and construction contracts for the first MQ-25 demonstrators.

To fully exploit the potential of the MQ-25, the Navy should re-designate it as a multi-mission UAV. The initial version of the MQ-25 would remain focused on the aerial refueling mission to avoid delays in program development. The Navy could then develop modifications that would enable it also to conduct ISR, attack, and EMW missions in appropriate operational environments. Alternatively, the Navy could explore ways for the UCAV to also conduct the refueling mission once it is fielded.

Long-range Fighter (FA-XX)

Escort and OCA operations will require a long-range fighter to counter enemy DCA CAPs and enable land-based or CVW strike aircraft to closely approach targets and use smaller, short-range strike weapons. The range, sensor capability, and weapons capacity needed in a future long-range fighter could be provided with a modified version of an existing fighter or strike-fighter by shifting weapons payload to fuel capacity and incorporating additional fuel efficiency measures.

Planned Aircraft Retained in Proposed 2040 CVW

Between FY 2019 and FY 2023, the Navy plans to complete the procurement of MH-60R ASW and MH-60S logistics helicopters, E-2D AEW&C aircraft, and E/A-18G EW strike-fighters. The proposed 2040 CVW includes MH-60s and E-2Ds, which may require some life extension; both aircraft will, however, have reduced roles in 2040 compared to today due to their constrained range and survivability.

The proposed 2040 CVW would buy the first half of the F-35C program to supply one squadron per CVW, but the second squadron would be replaced with the FA-XX. Although not formally part of the CVW, the proposed 2040 CVW assumes the Navy’s ongoing plan to replace the C-2A logistics aircraft with the CMV-22 Osprey. The 2040 CVW also includes in its helicopter squadrons a medium-altitude, long-endurance (MALE) Vertical Take-Off and Landing Tactical Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (VTUAV) based on ongoing development efforts in the Navy and Marine Corps for an unmanned multi-mission aircraft, known as the Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) Expeditionary (or MUX).

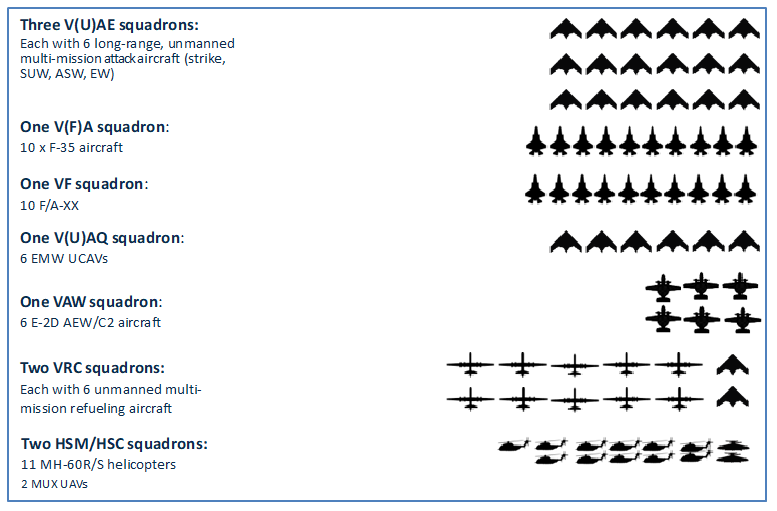

Future CVW Composition

CSBA’s proposed 2040 CVW, shown below, includes the new and existing aircraft described above in a mix that improves the Navy’s CVW range, endurance, survivability, and payload capacity. Whereas the Navy’s planned CVW would center around 20 F-35C and 24 F-18 E/F or FA-XX strike-fighters, the proposed CVW is built around 18 UCAVs, ten FA-XX fighters, ten F-35C strike-fighters, and six UCAV-based AEA aircraft. Although the aggregate payload capacity of the proposed CVW is about the same as the Navy’s plan, the 2040 CVW could deliver its payload twice as far or remain on station much longer.

The proposed CVW also incorporates more specialized aircraft to address the growing capability of great power competitors. The long-range FA-XX fighter will be better able to counter enemy DCA aircraft, and the UCAV will be a more effective platform to support long-endurance CAP missions for air defense, ASW, SUW, and ISR&T than the Navy’s planned CVW of short-range strike-fighters. The CVW also includes more MQ-25 tankers to maximize the CVW’s reach and endurance.

Making the New CVW a Reality

There are several different combinations of programmatic changes that could be used to reach the proposed CVW by 2040. CSBA recommends the following actions, starting with the President’s Budget for FY 2020. Notably, the new procurement proposed by this study would not begin until after the FY 2020–2024 Future Year’s Defense Plan (FYDP), although some research and development funding would be repurposed within the FYDP.

- Sustain procurement of F/A-18 E/Fs as planned through 2023. Although the future CVW requires half the strike-fighters of the Navy’s planned CVW, these aircraft will fill near- to mid-term capacity gaps. F/A-18 E/Fs still in service by 2040 can be used in place of UCAVs or F-35Cs if those aircraft are not yet fully fielded.

- Sustain F-35C procurement as planned through the first half of production, ending in 2024, to support the proposed 2040 CVW’s squadron of ten F-35Cs.

- Develop the FA-XX fighter during the 2020–2024 timeframe as a derivative of an existing aircraft, with production starting in 2025. Block III F/A-18 E/Fs and F-35Cs will be in production during the FY 2020–2024 FYDP, and either they or another in-production fighter or strike-fighter could be modified into an FA-XX. Although this approach will require some additional funding for non-recurring engineering between about 2020 and 2024, it will save billions of dollars compared to the Navy’s plan to develop a new fighter aircraft from scratch.

- Develop a low-observable UCAV attack aircraft during the 2020–2024 timeframe, with production starting in 2025. Although the UCAV could be based on an existing design such as the X-47B, 1–2 years of development may be needed to create a missionized version.

- Continue development of the MQ-25, transitioning the program to the UCAV-based refueling aircraft when sufficient attack UCAVs are fielded. Increase the overall procurement of MQ-25 and UCAV-based refueling aircraft to support twelve per CVW.

- Retire E/A-18Gs as they reach the end of their service lives starting in the late 2020s, replacing their capability with NGJ-equipped UCAVs and UAV- and missile-expendable EMW payloads.

- In concert with the U.S. Marine Corps, field a MALE rotary-wing UAV such as the Tactically Exploitable Reconnaissance Node (TERN), which can augment CVW helicopter squadrons and could take over some of their ASW operations by the mid-2030s.

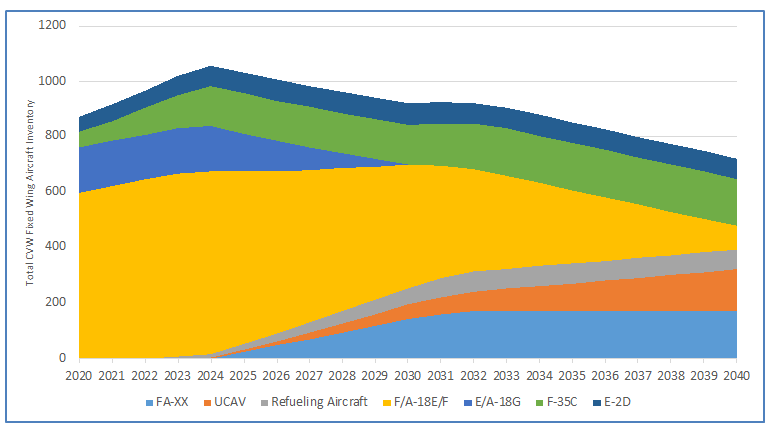

The fixed-wing carrier aircraft inventory associated with these recommendations is shown below. Under this plan, research and development of the planned MQ-25, modified FA-XX, and new UCAV would occur during the 2020–2024 timeframe, with production of new aircraft starting in 2025. Today’s F/A-18 E/Fs and E/A-18Gs would begin retiring in the late 2020s, to be replaced by UCAVs. The overall inventory of CVW aircraft will decrease as unmanned aircraft replace manned platforms, because operators and maintainers of unmanned aircraft can practice using simulators that will be as realistic as actual UAVs, eliminating the need for unmanned aircraft in training squadrons or in fleet squadrons that are not deployed or preparing to deploy. The smaller number of aircraft and squadrons results in a cost savings for unmanned aircraft compared to manned aircraft.

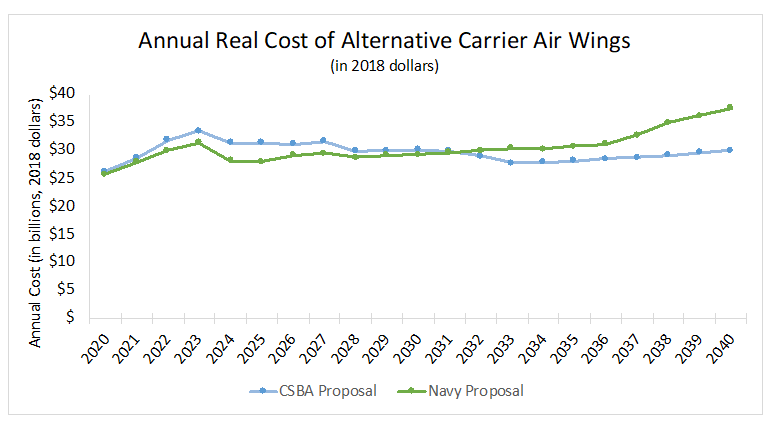

The approximate cost of the proposed 2040 CVW is shown below. Except for developmental spending associated with the proposed UCAV, proposed new development, procurement, and operations spending does not begin until FY 2024. The cost associated with the proposed 2040 CVW is less than the Navy would likely incur with its planned strike-fighter focused CVW. The continued reliance on manned strike-fighters results in a larger overall number of aircraft being required compared to the proposed CVW, primarily to train pilots and maintain their proficiency when not deployed. The higher aircraft inventory increases operations and maintenance (O&M) costs during the first decade of the period shown and raises procurement costs during the 2030s when today’s F/A-18 E/Fs are replaced with a new manned strike-fighter.

A Clear Choice

The proposed 2040 CVW will be more expensive in the near-term than the Navy’s planned CVW, but the Navy will need to incur these additional costs if it is to prevent carrier aviation from becoming irrelevant to the most pressing defense challenges of the near future. The threats posed by great power competitors, and increasingly by regional powers such as Iran and North Korea, preclude relying on legacy capabilities to protect American allies and interests overseas.

Naval forces will be instrumental in deterring and defeating aggression by these adversaries, as described in the NDS. Carrier air wings provide the ability to sustain naval combat operations beyond the first few days, when ship and submarine missile inventories are depleted. Without a clear plan to improve the Navy’s CVWs, the United States may not be able to implement its defense strategy, and DoD leaders would need to reconsider if they want to continue the Navy’s investment in carrier aviation or shift resources to other, more effective, capabilities.

Bryan Clark is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. He was a career enlisted and officer submariner and held several positions in the Chief of Naval Operations staff, including Director of the CNO’s Commander’s Action Group.

Featured Image: South China Sea (Feb. 10, 2018) The Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70) transits the South China Sea. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Third Class Jasen Morenogarcia/Released)