By Robert Holzer and Scott C. Truver

“Stand by, Admiral Gorshkov, Aegis is at Sea!”

The U.S. Navy’s first Aegis-equipped surface warship, the USS Ticonderoga (CG-47), joined the Fleet in January 1983, and all-but dared the Soviet Navy to take its best anti-ship cruise-missile shot.

The Navy’s newest Aegis guided-missile destroyer in the fall 2014, the USS Michael Murphy (DDG-112), was commissioned in December 2012. Murphy is the Navy’s 102nd Aegis warship. Another 10 Aegis DDGs are under construction, under contract or planned––a remarkable achievement!

Aegis surface warships were conceived during the height of the Cold War to defend U.S. aircraft carrier battle groups from massed Soviet aircraft and anti-ship cruise missile attacks. With the early retirements/layups of as many as 16 of 27 Aegis cruisers (beginning with Ticonderoga’s decommissioning in September 2004), some observers characterize the Aegis Weapon System (AWS) as an old, legacy program, whose time has passed.

This is just plain wrong. No other naval warfare capability has experienced more upgrades and significant changes over the years than Aegis. As global threats evolved and new missions emerged, so too have Aegis’ capabilities “flexed” to meet increasingly daunting operational demands. Even more advanced versions of Aegis are planned in the years ahead.

To paraphrase a classic 1990s Oldsmobile commercial: This is not your “father’s Aegis!”

Aegis: Don’t Leave Homeports without It

![]() Without doubt, the Aegis Weapon System in 1983 represented a true revolution in shipboard air defense. Based on an enormous investment in time, resources and management focus, Aegis was the first truly integrated ship-based system. It brought together radar and sensor detection, tracking and missile interception into a coherent, well-integrated weapon system. This was a staggering engineering achievement for the time. And was the culmination of nearly 40-years of Navy experience in confronting and overcoming ever more dangerous air defense challenges, beginning with kamikaze attacks in the waning months of World War II and extending to Soviet Backfire bombers in the 1970s and 1980s.

Without doubt, the Aegis Weapon System in 1983 represented a true revolution in shipboard air defense. Based on an enormous investment in time, resources and management focus, Aegis was the first truly integrated ship-based system. It brought together radar and sensor detection, tracking and missile interception into a coherent, well-integrated weapon system. This was a staggering engineering achievement for the time. And was the culmination of nearly 40-years of Navy experience in confronting and overcoming ever more dangerous air defense challenges, beginning with kamikaze attacks in the waning months of World War II and extending to Soviet Backfire bombers in the 1970s and 1980s.

Originally focused primarily on the fleet air defense/anti-air warfare mission—hence, the “Shield of the Fleet” slogan––Aegis has steadily expanded its mission set over the decades to successively include cruise missile defense, area theater ballistic missile defense, integrated air and missile defense (IAMD), and longer-range ballistic missile defense (BMD) cued by space-based sensors. (In Greek mythology, Aegis was the shield wielded by Zeus.) As more advanced radars and missiles enter the inventory in coming years, Aegis will play an increasingly important role in national BMD, too.

During the past 30 years, Aegis has expanded beyond the original 27 Ticonderoga-class cruisers to also include the entire fleet of 75 Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyers. In mid-2014, Aegis is deployed on 84 ships: 22 cruisers and 62 destroyers. Thus, Aegis is no longer just the “backbone” of the surface fleet, but constitutes its “central nervous system” as well.

Build a Little…

Critical to Aegis’ ability to evolve and defeat new threats—some only dimly seen when the program was conceived more than 40 years ago—has been an enormous capacity for growth that was built into the system from its very beginning. This growth in mission capacity can be attributed to the late-Rear Adm. Wayne E. Meyer, who guided the development of Aegis and worked tirelessly to ensure the architecture retained sufficient flexibility to accommodate future changes in threats, missions and technology. Long known as the “Father of Aegis,” Meyer trusted empirics and not analytics. In his view, the real ground truth that undergirds weapon system performance comes from engineering or operational test data. As such, he embraced a simple, but powerful, management mantra: “Build a little, test a little, learn a lot!”

Meyer’s technical and engineering driver was the warfighting requirement to get an interim, initial Aegis capability into the fleet to solve the warfare problem: “Detect, Control and Engage.” Rear Adm. Timothy Hood, the Naval Sea System Command (NAVSEA) program executive officer for theater air defense in the early 1990s, would say whereas detect-control-engage identified the Aegis warfare problem, build-a-little, test-a-little, learn-a-lot described the Aegis process. The specific functional/performance cornerstones of Aegis then put real numbers to the capabilities Aegis engineers were striving to meet—all to achieve the ultimate objective of putting Aegis to sea. (1)

Aegis cornerstones have guided the program for more than four decades. Fundamentally, Meyer made project decisions based on the best technical approach. As such, he instilled a rigorous systems engineering discipline in the Aegis program and established key performance factors. He then defined these factors to be quantitatively expressed to serve as guidance for engineering trade-offs and compromises to address the detect-control-engage warfare problem. These cornerstones required constant attention and were reflected in what Meyer called “people, parts, paper and [computer] programs.”(2)

In the end, Meyer successfully translated the Aegis cornerstones into acquisition process principles that informed decision-making at every level. To keep Aegis system-engineering development moving forward in advance of a Navy decision on ship design, Meyer employed the so-called Superset design and engineering approach. Superset called for integrating the largest set of combat system elements (sensors, control systems and weapons) and then down-designing that superset of capabilities to meet specific ship suites when finally approved. The payoff was in getting Aegis to sea on budget, on time. This philosophy continues to animate the Aegis program.

Baseline Continuous Improvement

Meyer’s project office opted to introduce initial, interim capabilities via continuous construction lines for cruisers and destroyers (rather than expensively introducing new ship classes with block upgrades) to accommodate Aegis advances. The engineering development approach that enabled this decision was a process practice called the Aegis Combat System Baseline Upgrade Program. Each Aegis Baseline—focused primarily on major systems and upgrades—was an engineering package of improvements introduced on two-to-four year cycles. A major warfighting change—for example, the introduction of the Mk 41 Vertical Launching System (VLS), Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile (TLAM) and an integrated anti-submarine warfare (ASW) suite into Aegis—would call for a new engineering baseline. The introduction of these three components in fact constituted Aegis Baseline 2. In addition, the Baseline Upgrade Program allowed for retrofits. Under the principle “Forward Fit before Backward Fit,” engineering and design focused on new construction ships while at the same time enabling cost-effective retrofits of Aegis ships already in the fleet.

Meyer’s project office opted to introduce initial, interim capabilities via continuous construction lines for cruisers and destroyers (rather than expensively introducing new ship classes with block upgrades) to accommodate Aegis advances. The engineering development approach that enabled this decision was a process practice called the Aegis Combat System Baseline Upgrade Program. Each Aegis Baseline—focused primarily on major systems and upgrades—was an engineering package of improvements introduced on two-to-four year cycles. A major warfighting change—for example, the introduction of the Mk 41 Vertical Launching System (VLS), Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile (TLAM) and an integrated anti-submarine warfare (ASW) suite into Aegis—would call for a new engineering baseline. The introduction of these three components in fact constituted Aegis Baseline 2. In addition, the Baseline Upgrade Program allowed for retrofits. Under the principle “Forward Fit before Backward Fit,” engineering and design focused on new construction ships while at the same time enabling cost-effective retrofits of Aegis ships already in the fleet.

To ensure Aegis outpaces today’s developing threats, Navy program officials with the Program Executive Office for Integrated Warfare Systems (PEO IWS) now exercise development and management oversight for service combat systems to inject new capabilities into Aegis through this time-tested approach to upgrades and improvements. Today’s baselines continue to be added to new ships during their construction phase and deployed ships when they undergo their specified shipyard maintenance cycles.

Initial baselines focused on adding only a few, discrete upgrades to Aegis. As this process has matured and Navy program engineers and system designers have accumulated more experience in understanding the nuances of Aegis baseline upgrades, their complexity, capabilities and capacities have grown exponentially. Baselines have grown in terms of the amount of new capabilities added to Aegis at each modernization interval to address both the pace of technological change and the acceleration of new threats and challenges. This is an ever-expanding OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide and Act) loop that Aegis is well accustomed to facing.

As of the fall 2014, a total of eight specific baselines have been fielded across the fleet of Aegis-equipped ships. A more advanced Baseline 9 version is undergoing its operational test and evaluation phase and will be deployed next year.

Baseline upgrades have added the following key capabilities to Aegis-equipped cruisers and destroyers over time since Baseline 0 that went to sea with the first Aegis warship, Ticonderoga. Within these numbered baselines, multiple versions at times have been introduced to accommodate minor variations to a particular Aegis combat system element development or shipbuilding program. Broadly stated, these baseline upgrades include:

Baseline 1: The original Aegis system attributes deployed on the first Ticonderoga-class cruisers (CGs 47-51) that consisted of the SPY-1A radar, the Mk-26 trainable launcher and the Navy’s mil-spec UYK-7 computers. Baseline 1 equipped the first five Aegis cruisers with the final combat system computer program whose configuration was based on the lessons learned from Ticonderoga’s first deployment.

Baseline 2: The first real upgrade to Aegis deployed on the next tranche of cruisers (CGs 52-58) that introduced, as stated above, the Mk 41 VLS, Tomahawk and an upgraded ASW suite, the SQQ-89, with the SQS-53B sonar. Introduction of VLS and Tomahawk gave Aegis cruisers a long-range strike, land-attack capability. As well, the VLS cells led to use of the larger, more capable SM-3 missile that would greatly expand Aegis air defense capabilities to include BMD.

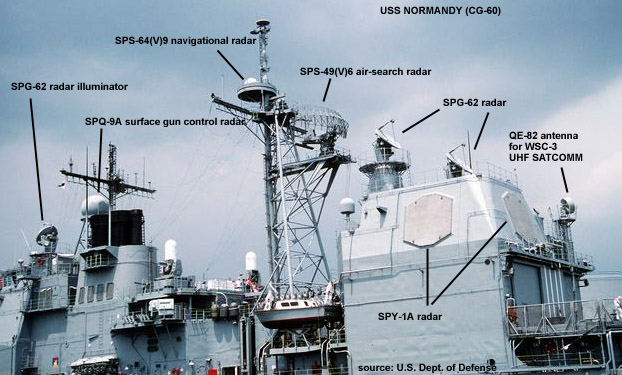

Baseline 3: These upgrades were added to the later-built cruisers (CGs 59-64) and included the more advanced SPY-1B version of the radar, along with the SM-2 Block II missile and new UYQ-21 computer consoles. By enabling use of the SPY-1B, this baseline was a major capability enhancer with respect to electronic counter-counter measures (ECCM).

Baseline 4: This baseline was the first to accommodate both cruisers and destroyers. Improved capabilities were added to the final lot of cruiser construction (CGs 65-73) and the first construction lot of the newer Arleigh Burke-class destroyers (DDGs 51-67). The new capabilities added to the cruisers included the next-generation UYK-43/44 computers and the latest-version of the SQS-53C sonar. The DDG upgrades included the new SPY-1D radar, SQQ-89(V) ASW system and UYK-43/44 computers. Of note, the SPY-1D, though identical to the SPY-1B, required only a single deckhouse in the destroyer superstructure since it used only a single set of power amplifiers (instead of the two in the fore and aft deckhouses on the cruisers). Later the SPY-1B(V) radar was retrofitted to the cruisers beginning with CG-59.

Baseline 4: This baseline was the first to accommodate both cruisers and destroyers. Improved capabilities were added to the final lot of cruiser construction (CGs 65-73) and the first construction lot of the newer Arleigh Burke-class destroyers (DDGs 51-67). The new capabilities added to the cruisers included the next-generation UYK-43/44 computers and the latest-version of the SQS-53C sonar. The DDG upgrades included the new SPY-1D radar, SQQ-89(V) ASW system and UYK-43/44 computers. Of note, the SPY-1D, though identical to the SPY-1B, required only a single deckhouse in the destroyer superstructure since it used only a single set of power amplifiers (instead of the two in the fore and aft deckhouses on the cruisers). Later the SPY-1B(V) radar was retrofitted to the cruisers beginning with CG-59.

Baseline 5: These upgrades were targeted to Burke-class destroyers (DDGs 68-78) and consisted of SPY-1D radar, SLQ-32 electronic countermeasures system, SM-2 Block IV missile, Link-16 system and Combat Direction Finding. Introduction of this baseline required a major effort in the track file and associated track processing in the command and decision (C&D) display enabling Aegis to become a major player in battle group networks.

Baseline 6: Brought a significant list of new capabilities to Aegis destroyers (DDGs 79-90) including SPY-1D(V) with modifications for littoral operations. It introduced the Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC), Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM) and UYK-70 display consoles. Baseline 6 was a notable transition from a Navy mil-spec-based combat system to one with a fully commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) hardware environment. A mil-spec/COTS hybrid, it was the first forward fit of COTS computers for tactical purposes that provided area air warfare, CEC and an area theater ballistic missile defense (TBMD) capability for Baseline 6 DDGs and six upgraded Baseline 6 cruisers.

Baseline 7: The last baseline designed specifically for forward-fit into new construction ships, it represented a full conversion to commercial computers, i.e., the complete transfer to COTS processing. The baseline added the Tomahawk fire control system upgrade and Theater Wide BMD to Burke-class destroyers (DDGs 91-112). The introduction of the third-generation SPY-1D(V) radar provided major performance enhancements against stealth threats and all threats in the littoral environments. Baseline 7 DDGs had the capability for network-centric operations: they were enabled to employ the so-called Tactical Tomahawk that was reprogrammable in-flight, e.g., for use against ships and mobile land-attack targets.

Baseline 7: The last baseline designed specifically for forward-fit into new construction ships, it represented a full conversion to commercial computers, i.e., the complete transfer to COTS processing. The baseline added the Tomahawk fire control system upgrade and Theater Wide BMD to Burke-class destroyers (DDGs 91-112). The introduction of the third-generation SPY-1D(V) radar provided major performance enhancements against stealth threats and all threats in the littoral environments. Baseline 7 DDGs had the capability for network-centric operations: they were enabled to employ the so-called Tactical Tomahawk that was reprogrammable in-flight, e.g., for use against ships and mobile land-attack targets.

Baseline 8: Brought COTS and open architecture to Baseline 2 equipped Aegis cruisers. The baseline captured tailored upgrades from new construction Baseline 7.1R destroyers (DDG 103-112), bringing the seven cruisers greater capacity for technical data collection and enhanced area air warfare and CEC.

Baseline 9: The latest version of the long-running and highly successful Aegis upgrade process, this baseline will bring significant improvements to the Fleet in several key respects. The new baseline brings radical changes to the software environment creating a true open-architecture computing framework. Common source code shared among Baseline 9 variants enhances software development, maintenance and re-use, boosting the capability to support combat system interoperability improvements and enhanced capacity and functionality.

Major Warfighting Improvements

Baseline 9 will deliver three major warfighting capability improvements. These are: the Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air (NIFC-CA), Integrated Air and Missile Defense and Enhanced Ballistic Missile Defense.

The NIFC-CA capability for Baseline 9 cruisers and destroyers provides integrated fire control for theater air and anti-ship cruise missile defense, greatly expanding the over-the-horizon air warfare battle space for surface combatants by enabling third-party targeting of threats and use of “smart” missiles. NIFC-CA is valuable since it will allow greater performance of the Aegis radar over land and in the congested littorals where radar signals can be degraded given the topography and other local conditions. NIFC-CA allows Aegis to conduct over-the-horizon targeting using Standard anti-air missiles against targets based on data and other information received via the CEC net from off-board sensors such as enhanced E-2D Hawkeye aircraft.

IAMD brings the Fleet a more comprehensive capability to conduct ship self-defense, area air defense and ballistic missile defense missions at the same time. A core Navy mission driving capabilities for mobile, persistent, multi-mission Surface Forces, IAMD enables Aegis-equipped ships to optimize shipboard radar resources rather than forcing the radar to devote its energy to only one mission at a time. This full-up capability in all air- and missile-defense domains represents another major advance in the continuously evolving AWS capabilities against emerging threats. The Aegis SPY-1D radar uses the new Multi-Mission Signal Processor (MMSP) software package that is the centerpiece of IAMD. The MMSP integrates signal-processing inputs from the combat system’s BMD signal processor and the legacy Aegis signal processor for the radar. Prior to MMSP a ship had to devote the bulk of her radar’s power resources to tracking the more demanding BMD threat with a corresponding diminution to the air defense mission.

IAMD brings the Fleet a more comprehensive capability to conduct ship self-defense, area air defense and ballistic missile defense missions at the same time. A core Navy mission driving capabilities for mobile, persistent, multi-mission Surface Forces, IAMD enables Aegis-equipped ships to optimize shipboard radar resources rather than forcing the radar to devote its energy to only one mission at a time. This full-up capability in all air- and missile-defense domains represents another major advance in the continuously evolving AWS capabilities against emerging threats. The Aegis SPY-1D radar uses the new Multi-Mission Signal Processor (MMSP) software package that is the centerpiece of IAMD. The MMSP integrates signal-processing inputs from the combat system’s BMD signal processor and the legacy Aegis signal processor for the radar. Prior to MMSP a ship had to devote the bulk of her radar’s power resources to tracking the more demanding BMD threat with a corresponding diminution to the air defense mission.

Enhanced BMD comes with Baseline 9’s open architecture environment that will provide both a launch-on remote (LoR) and engage-on-remote (EoR) capability for Aegis where the interceptor missile uses tracking data provided from remote, off-board (land, sea, airborne and space-based) sensors to launch against and to destroy missile threats. Previous baselines have progressively expanded the LoR capability for Aegis BMD “shooters” to launch missile interceptors earlier in the target missile’s trajectory. Baseline 9’s open architecture will accommodate the Aegis BMD 5.1 system software upgrade to enable an engage-on-remote capability that advances launch-on-remote by providing an organic track to the interceptor missile late in its flight. To the extent that LoR and EoR can provide enhanced capability to the Block IA, IB and IIA versions of the Standard missile—supported by a netted sensor framework—they have the potential to provide BMD to strike group and homeland defense missions.

Enhanced BMD comes with Baseline 9’s open architecture environment that will provide both a launch-on remote (LoR) and engage-on-remote (EoR) capability for Aegis where the interceptor missile uses tracking data provided from remote, off-board (land, sea, airborne and space-based) sensors to launch against and to destroy missile threats. Previous baselines have progressively expanded the LoR capability for Aegis BMD “shooters” to launch missile interceptors earlier in the target missile’s trajectory. Baseline 9’s open architecture will accommodate the Aegis BMD 5.1 system software upgrade to enable an engage-on-remote capability that advances launch-on-remote by providing an organic track to the interceptor missile late in its flight. To the extent that LoR and EoR can provide enhanced capability to the Block IA, IB and IIA versions of the Standard missile—supported by a netted sensor framework—they have the potential to provide BMD to strike group and homeland defense missions.

Ultimately, EoR will enable the shooter to complete the intercept. LoR and EoR thus add to layered defense, a critical capability for the successful intercept of longer-range and fast-flying missiles. When launch-on-remote and engage-on-remote become operational, the Aegis system can reach further into the joint and combined arenas. For example, Aegis open architecture provided by the Aegis BMD 5.0 family of system software upgrades will make it easier for allies and partners to integrate new weapon systems and sensors into their Aegis systems. This enhanced network integration will legitimize the concept of “any sensor, any shooter” to extend the battlespace and defended area.

Past Being Prologue…

Aegis has enjoyed a remarkable history in the U.S. Navy—as well as several foreign navies––and with the deployment of the new Baseline 9 version, and most likely other upgrades coming, there is no final chapter yet to be written for this workhorse capability. Aegis has truly evolved from the “Shield of the Fleet” to the Fleet’s “Central Nervous System” and more. A system originally designed to launch surface-to-air missiles against air-breathing bombers and cruise missiles has evolved into a networked combat system that can target land-launched ballistic missiles and even satellites in space—and destroy them. While its roots are traceable to the Cold War, Aegis is firmly focused on overcoming the challenges and threats the U.S. Navy faces in tomorrow’s murky and increasingly dangerous future.

Robert Holzer is senior national security manager with Gryphon Technologies’ TeamBlue National Security Programs group. Dr. Truver is TeamBlue’s director.

(1) Rear Adm. J.T. Hood, USN (Ret.), “The Aegis Movement—A Project Office Perspective,” Naval Engineers Journal: The Story of Aegis, Special Edition (2009/Vol. 121 No. 3), p. 194.

(2) Robert E. Gray and Troy S. Kimmel, “The Aegis Movement,” The Story of Aegis, op.cit., p. 41.