By Chris Bassler and Steve Benson

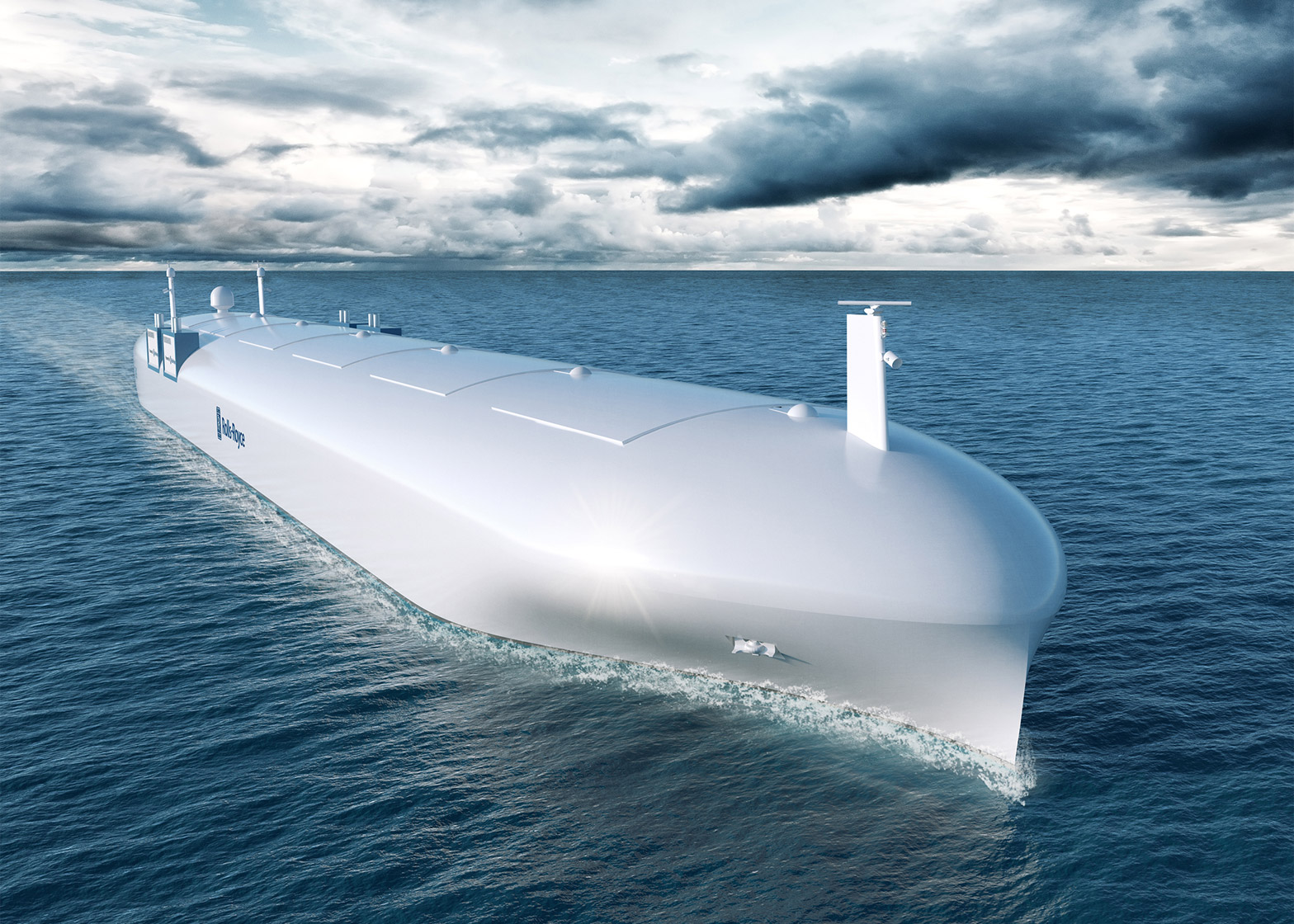

On October 6 2020, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper debuted Battle Force 2045. As foundational elements of U.S. naval force design, Secretary Esper emphasized the importance of very long-range precision fires in volume, while also ensuring naval forces continue to operate at the forward edge of American interests. The U.S. Navy has an opportunity to immediately use existing ship types that are currently fielded in large numbers as manned auxiliary-strike platforms, while leveraging ongoing investments and technology maturation in the commercial shipping world for future unmanned naval platforms. The Navy can become a fast-follower, leveraging these investments and technology developments to rapidly field a future autonomous auxiliary-strike platform as a key part of a future unmanned naval force structure.

Over the past several years, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps have been focused on developing and implementing a concept for Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO). DMO, along with the associated Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment (LOCE) and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concepts, all seek to address the increasing threat posed by the proliferation of sophisticated weaponry and combat systems among great powers and potential proxies. Additionally, the 2018 National Defense Strategy highlights the distinct and important roles of the contact, blunt, surge, and homeland defense layers of the Joint Force.

The subsequent implications for U.S. naval forces, joint forces, and combined forces are broad, but to date, have remained nascent in their implementation. The simple message is that ceding the littoral regions of the world to an adversary is unacceptable to the United States and likeminded allies and partners. The Littoral Combat Ship was an initial, albeit flawed, effort to address a long-debated return to littoral operations – the dominant feature of naval operations throughout history. A hybrid commercial-military approach to force projection in contested environments deserves closer examination, and is an approach that is immediately available. It offers an evolutionary and rapid path to the future.

Fundamental Principles in a 21st Century Maritime Competition: Numerous, Distributed, Persistent, and Nondescript

A critical aspect of the DMO concept that has rightly received attention is the need to resupply and rearm combatants in order to conduct protracted operations. Doing so in an environment where fixed targets, such as ports as well as large force concentrations are becoming increasingly vulnerable poses an ever-growing challenge. An alternative approach is needed, whereby unit-level maritime surface munitions batteries would be mobile and available for use when needed, rather than located in afloat resupply stockpiles. This approach, and the use of regionally-oriented vessels, would be linked to demands of littorals operations that are already prime considerations in the design and construction of commercial vessels in global trade today. In contrast, custom military-first solutions for this purpose run the risk of being unaffordable.

Although the Marine Corps and the Army are developing mobile land-based missile batteries and will be a crucial part of the missile strike capacity in the U.S. Marine Corps’ new Littoral Maneuver Regiments (LMRs), such forces will nonetheless face challenges. These include gaining and maintaining basing access from host nations, sufficient protection and maneuver to minimize attrition from preemptive strikes, and providing sufficient stockpiles for reloading land-based missile batteries.

As a result, sea-based solutions must also be considered, especially to support stand-in forces in the contact layer. However, limits will persist for surface platform rearming at sea. Approaches that employ weapons in quantity from tactical fighters or unmanned aerial vehicles face similar challenges, while being more hobbled by limits of endurance and payload. Although the deployment of the Virginia Payload Module will provide additional covert strike capacity from SSNs, this alone will not be sufficient to address the need.

U.S. Navy experiments with test-bed platforms, like DARPA’s Sea Hunter and the Strategic Capabilities Office’s (SCO) Overlord, continue to inform some of the US Navy’s thinking for the large and medium unmanned surface vessels (LUSV and MUSV). Although these efforts have yielded valuable lessons, significant additional modifications and enhancements are still required in order to become operationally deployable assets. The roadmap of potential solutions, specifically for unmanned surface capabilities and platforms, is still coming into focus, and emphasis remains on MUSV and LUSV as the key surface platforms for acquisition programs of record. Some have advocated for concepts and experimentation using missile barges or converted commercial vessels, such as container ships.

It is time for the U.S. Navy to step forward in support of the USMC’s renewed creative thinking surrounding land-based, stand-in forces and develop a “Littoral Maneuver Flotilla” for the complementary naval component to the LMR. While supporting, and supported by, land-based forces, these floating missile magazines could be used to coordinate more complex multi-axis attacks, drastically complicating adversary planning and capabilities for effective defense.

A Missing Piece for a Littoral Maneuver Flotilla: The Auxiliary-Strike Surface Platform

In order to apply the fundamental principles of numerous, distributed, persistent, and nondescript, a specific set of missions that can be appropriately and advantageously grouped together must be considered. These naval missions include logistical resupply, including both ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore; a floating munitions battery for strike, anti-surface warfare (ASuW), and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) missions; convoy escort; and mobile minelaying. A 2020 CRS report noted:

“The Navy wants LUSVs to be low-cost, high-endurance, reconfigurable ships based on commercial ship designs, with ample capacity for carrying various modular payloads — particularly anti-surface warfare (ASuW) and strike payloads, meaning principally anti-ship and land-attack missiles.”

Some nations (such as Russia, China, and Israel), have developed containerized deck-mounted weapons and others are contemplating them. However, their small numbers, need for supporting equipment, and conspicuous posture lessen their potential operational significance. Instead, a floating vertical launch system (VLS) battery could be employed to launch missiles for strike missions (anti-ship or land-attack), torpedoes, or mobile mines against surface or undersea targets. However, a floating VLS battery would still need to be controlled by a mothership or some other local controller (e.g. a surface combatant, aircraft, or spacecraft). In many cases, artificial intelligence is still not sufficiently mature and sufficient trust in autonomous systems has not been developed. Moreover, in addition to sophisticated net-enabled weapons, a floating VLS battery would require offboard targeting and fire control.

It is worth considering alternatives to the commercially adapted, but more militarized designs of the LUSV and MUSV, which will be neither cheap, nor non-descript. In the late 2000s, NAVSEA conducted a study that looked at using Military Sealift Command dry cargo ships as first salvo strike platforms, leaving surface combatants for follow-on engagements. However, this concept was not pursued, and the Navy instead focused on different technical approaches to enable rearming at sea. With the recent track record of naval ship design, a “clean sheet” new T-AKE class would likely result in a complex, high-cost, and conspicuous design.

Instead, handysize break bulk carriers sail in large numbers today and are IMO-compliant double-hull designs. Use of such existing ships would allow the Navy and Marine Corps to gain immediate experience with the concept and further develop and refine approaches, while only requiring small crews of operators. At the same time, during the last five years, efforts have been underway to develop and experiment with autonomous commercial shipping, including major ongoing efforts in Finland, Norway, Sweden, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea, among others. As these autonomous ships mature and begin to sail in significant numbers in their respective regions, the Navy can then smartly shift over to employing these vessels for the auxiliary-strike role. In the framework of the NDS, these vessels would be a persistent contact force, but with blunt force abilities and capacity.

“Gray Man” at Sea: A Nondescript, Effective Platform for the Shell Game

An approach that initially leverages manned, break bulk vessels, and then progresses to unmanned autonomous shipping vessels will allow immediate fielding of increased numbers of surface strike assets, while at the same time developing, de-risking, and experimenting with key technologies as they mature. Indeed, it would follow the wisdom of Rear Admiral Wayne E. Meyer’s famous motto of “build a little, test a little, learn a lot” while rapidly expanding the number of distributed surface strike assets today and into the future. Deception would be enhanced by the clever use of ubiquitous common commercial hulls in this shell game.

Using commercial vessel ship classes that could accommodate weapons modules and launch cells (e.g. either Mk41 or Mk57 VLS) with minimal modifications would, at reasonable cost, substantially increase the numbers of launchers available that could be employed in the earlier stages of a conflict and support stand-in forces in the contact layer. The Mk57 VLS developed and employed on the DDG-1000 includes options for additional munitions and extra hardening for payload protection. The standardization of both Mk41 and Mk57 VLS permit numerous and varied weapons loadout options, and the VLS modules can be distributed in configurations within the ship to minimize risk of damage, while also confusing adversary targeting through both inter-ship and intra-ship deception. Instead of cumbersome and time-consuming weapons reloads in individual cells, replacing fully loaded modules with a quick swap-out in available ports or at safe-anchorages could be used for logistical sustainment.

Notional estimates would suggest these vessels could carry payloads ranging from 16 to 100 or more VLS cells, sufficient to have diverse payloads and enable effective strikes, while not allowing the vessels to become large and lucrative targets, whose potential loss would be unacceptable. The objective is to have numerous, dispersed, persistent and nondescript mini arsenal ships, not a small number of massive capital ship assets.

The break bulk vessels would enable minimally manned operations today. And as technologies mature, increased experience can be gained with optionally manned operations. By leveraging ongoing and evolving autonomous commercial shipping designs, a future auxiliary-strike platform should have zero manning. Commercial autonomous ships are being specifically designed to achieve long-duration voyages, where no human intervention is needed for maintenance. Leveraging these commercial efforts would mitigate the challenges associated with attempting to apply traditional Navy design approaches and tools to vessels outside of the intended design conditions, while addressing risks that key stakeholders have identified. For commercial airlines, A-level check maintenance (the lightest) intervals can be up to 1000 flight hours between maintenance, equivalent to about 40+ days of continuous sailing. For other military vehicle applications, platforms like the X-37B robotic spaceplane, which recently achieved a record-setting 780 days in orbit, spacecraft design, or DARPA’s NOMARS (No Maintenance Required Ship) project can provide important lessons and insights for application to longer durations. The movement of commercial shipping toward autonomous surface vessels will help to accelerate this longer-interval without maintenance for many maritime systems and subsystems. As these approaches mature, the Navy should begin by establishing a goal of operating continuously for up to one month at sea without human intervention required, and then smartly work up to six-month intervals or longer.

For autonomous surface vessels, successful navigation in the highly trafficked and cluttered sea lanes is an operational imperative and is being pursued with urgency in the commercial world. One of the main successes from DARPA’s Sea Hunter program, in cooperation with the Navy, was the development and incorporation of COLREG compliant algorithms into the vessel’s operations. The vessel has been able to navigate unmanned round-trip journeys from California to Hawaii. In September 2020, a new commercial design began an unmanned navigation across the North Atlantic (a re-creation of the Mayflower journey, going from Plymouth, UK to Plymouth, Massachusetts). Data collected from recurring transits can be used to develop additional proxies and enhancements for autopilots. Several automotive companies use massive amounts of aggregated actual driver data to develop autopilot surrogates, and similar approaches could be applied.

Especially in peacetime, the commercial shipping approach of having remote control for a flotilla can be employed. Already today, we see how “remote tower” airport control technology has physically removed the need for air controllers to be located at each airfield. There is no reason that multiple flotillas could not be controlled from a single Maritime Operations Center (MOC), whether from a fixed location during peacetime, or from a nearby mothership or offboard platform during conflict. Especially for a crisis or conflict, understanding how these vessels would be employed when global or theater-wide regional network connectivity is not available, unreliable, or compromised is essential. Technologies to enable “network optional” command and control are already used today, such as optical recognition using “QR” codes, high capacity line-of-sight laser communications and data – to and from other maritime, airborne, or low earth orbit satellites, to enable “return to rendezvous point” commands, as well as unique deception techniques. Additionally, standardized launchers like the Mk41 or Mk57 VLS, coupled with rapidly advancing technologies for small satellites, will enable concepts for these vessels to self-launch and deploy their own unmanned aerial systems or tactical satellite constellations to provide temporary overwatch or secure communications relays.

The application of common vertical launch cell modules in nondescript and numerous commercial vessels provides an effective means to deliver this capability immediately, while also planning a path to leverage broader commercial technology advances in autonomous shipping. VLS cells maximize payload options through a standardized interface. Additional cargo space should be used for opportunistic resupply, port loading and offloading, to help reinforce consistent, nondescript behaviors. As a result, the platform could be considered as a mini-T-AKE (without underway replenishment), although indistinguishable from the numerous break bulk vessels, and in the near-future, from numerous autonomous shipping vessels. The same hull forms can be used for trade and military logistics in peacetime, organically growing a maritime Ready Reserve Force (RRF) (e.g. the British version of Ships Taken Up From Trade, or STUFT), for the U.S. and key allies and partners.

Expanding this approach beyond assets intended primarily for use in crisis or conflict will allow the ships to become more numerous and inexpensive, while also helping them be nondescript, as they exhibit common behaviors to numerous ships worldwide. With these vessels, the Navy should use common shipping trade routes as opportunities to hide in plain sight. Using routes, such as following the Japan-Taiwan-Philippines archipelago, or from Australia-Singapore-Vietnam, will provide ample opportunities for experience and experimentation, while also re-supplying U.S. bases, accessing key ports, and transiting with common traffic.

No specific paint schemes would be required, but due to the weapons payload, the ships would be flagged under U.S., ally, or partner, as required. This still presents a sufficient challenge to an adversary to confidently obtain positive combat identification, a considerably difficult part of the kill chain. These vessels would comply with legal requirements in peacetime, low intensity conflict, and up to war, while enhancing uncertainty as to their actual payloads and capabilities. Leveraging autonomous surface vessel designs, repurposed from seaborne trade for military purposes, and vice versa, can enhance continuous deterrence through the associated uncertainty of a “shell game” at sea, with autonomous surface auxiliary-strike ships as the cornerstone.

Additional Advantages: A Global Flotilla for Both Peacetime and Conflict

A key element of a successful strategy for great power competition involves leveraging the strengths of key allies and partners. Having common allied platforms in large numbers for both logistics and mobile weapons would provide distributed, persistent, and nondescript forces. These would enhance combined surface force and amphibious and ground maneuver operations in the littorals. Break bulk vessels can easily be built in many shipyards, due to their simple design, and can have shallow enough draft to operate in inland waterways. This offers the possibility for a modern but more operationally useful and plentiful “Liberty Ship” blended with characteristics of Q-ships. These vessels are useful in peacetime for sea-based commerce, as well as providing critical supporting forces in wartime, whether for attack, rearm, and resupply, while also hiding in plain sight, both physically and in the electromagnetic spectrum.

Development of autonomous commercial ships is technically feasible, and key allies and partners are leading the way with commercial investments. Leveraging the momentum and investments that key nations and major shipping companies are already undertaking, a consortium could be established between the U.S. Navy and several key allies to procure, adapt, field, and operate this class of platform. This would leverage common systems and approaches from commercial efforts, while enabling navies to focus on unique military systems development and maturation in parallel. For future autonomous surface platforms, by cooperating with select regional maritime partners, several primary (commercial shipping-based) variants could be procured and fielded, with customized attention to key regions (e.g. the Indo-Pacific, the Baltic, the Black Sea, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Arctic).

The cornerstone military capability of these ships revolves around the integration of Mk 41 or Mk 57 VLS cells. Allowing key nations to develop subsystems (hardware and software), especially autonomy enhancements to satisfy minimum mission requirements, and experiment would help to share the burden. The U.S. could take the lead on integration, to ensure maximum interoperability, as well as assess priority opportunities for enhanced capabilities. The recently established NATO Maritime Unmanned Systems (MUS) Initiative provides one such path where a virtuous cycle of missions, technologies, experimentation, and refinement can be realized.

Conclusion

The first Gulf War in 1991 provided valuable insight into the huge difficulties of “SCUD hunting” in the desert. The U.S. and key allies and partners can apply this approach to the maritime dimension of 21st century great power competition, for an advantageous cost-imposition strategy using cheap and mobile hiders to employ effective salvos at sea. This would shift the balance for cost-imposition in a way that is favorable in peacetime, while supporting continued economic development and positioning, and if needed, during crisis or conflict. In a hider-finder competition, the sheer volume of maritime traffic and persistence offer a key opportunity to advantage a hider, if it can remain nondescript. Application of common Vertical Launch System (VLS) modules into existing commercial vessels can provide numerous, distributed, persistent, and nondescript capability today, while also pursuing an accelerated path to leverage ongoing and significant commercial developments for autonomous shipping. The Navy should further pursue this concept in wargames and alternative future fleet architecture designs, with continuous feedback from at-sea experimentation. The U.S., with key partners and allies, should explore the use of these types of vessels, and effectively implement shell games at sea.

Chris Bassler is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA).

Steve Benson is President of Littoral Solutions Inc. and CDR, USN (ret’d).

Featured Image: A concept illustration of an autonomous Rolls-Royce vessel (Rolls-Royce image)