Rupprecht, Andreas. Flashpoint China, Chinese Air Power and Regional Security. Houston: Harpia Publishing, 2016. 80pp. $23.45

By Lieutenant Commander David Barr, USN

Introduction

Since his rise to power six years ago, thousands of analysts and policymakers across the globe have attempted to understand the intentions of, and the mechanisms employed toward, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China Xi Jinping’s seemingly expansionist vision for China. That vision, dubbed “The Chinese Dream” by Xi in 2012, solidified his plan for “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Although arguably vaguely defined, “The Chinese Dream” has been viewed by some as Xi’s call for rising Chinese influence on the international stage – economically, politically, diplomatically, scientifically, and militarily, i.e., China’s “grand strategy.”

In support of this vision, Xi has embarked on a multitude of political and military reforms and now, backed by one of the world’s most technologically-advanced militaries, Xi is ready to thrust his revitalized China further onto the world stage. During his opening speech to nearly 2,300 party delegates and dignitaries at the October 2017 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Xi publicly described the extraordinary complexity of China’s domestic and foreign policy challenges and opportunities: “Currently, conditions domestically and abroad are undergoing deep and complicated changes. Our country is in an important period of strategic opportunity in its development. The outlook is extremely bright; the challenges are also extremely grim.”1

In his new book, Flashpoint China, Chinese Air Power and Regional Security, Andreas Rupprecht, author of Modern Chinese Warplanes: Combat Aircraft and Units of the Chinese Air Force and Naval Aviation, attempts to break out of his comfort zone and succinctly capture the complexities of Chinese foreign policy and the geopolitical environment of the Asia-Pacific Region. The content of Flashpoint China is predominantly focused on Chinese regional security issues; however, in his introductory paragraph, Rupprecht states the goal of Flashpoint China is to “draw upon” Modern Chinese Warplanes and “offer an overview of potential military conflicts along the borders of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).”2 This is a laudable goal, for even attempting to synopsize the complexity of Chinese military history and foreign relations in a mere eighty pages would challenge the most knowledgeable defense and foreign relations expert. Yet for the most part, Rupprecht succeeds. There are some content areas however that could benefit from further research and development.

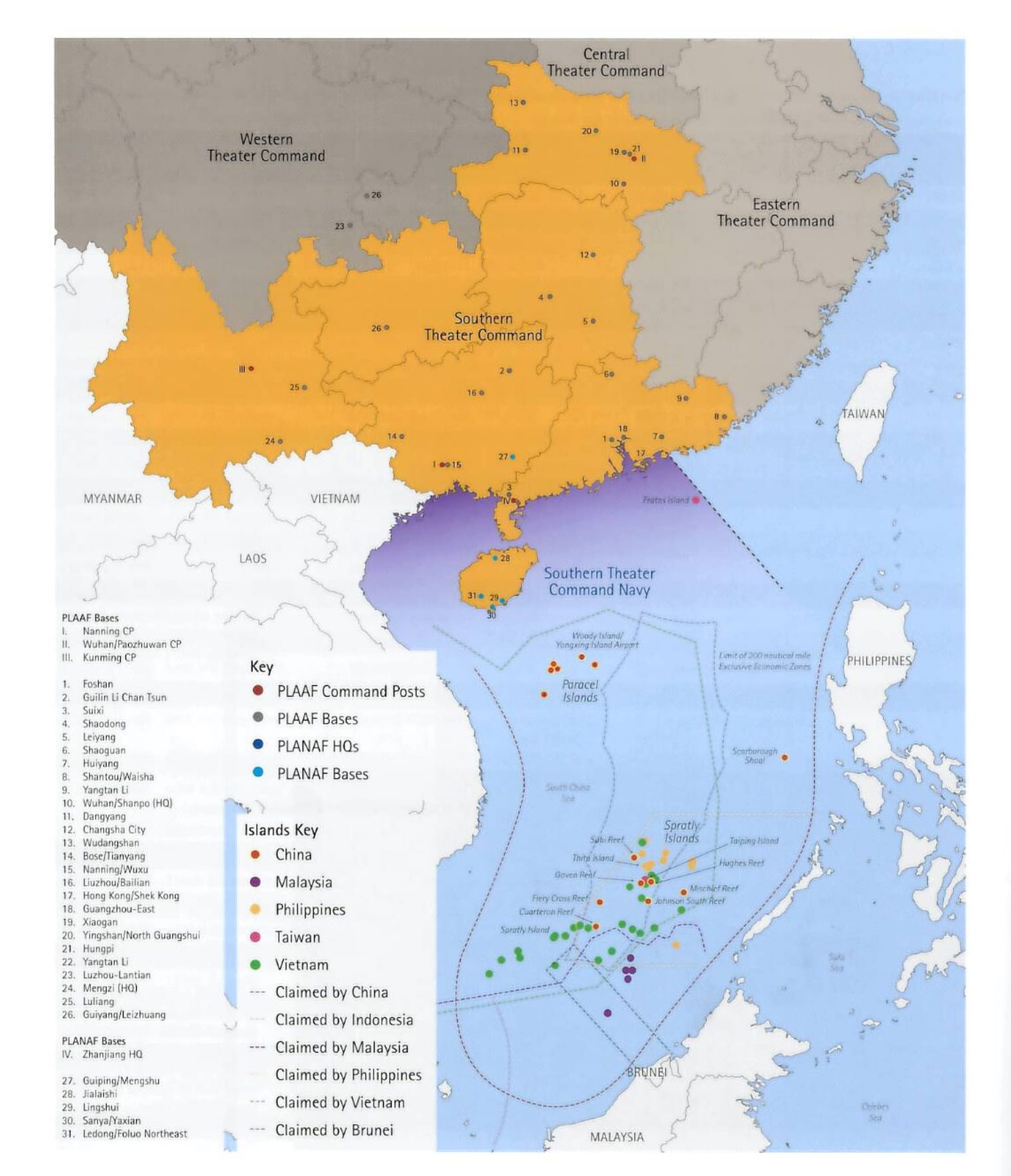

Following the introduction, Rupprecht utilizes Chapters Two through Five to succinctly introduce the various foreign policy concerns for China in each of its five Theater Commands. Each chapter opens with a succinct description of the nuanced histories behind each foreign policy concern, provides an overview of PLAAF and PLANAF capabilities available to each Theater Command, and closes with well-structured charts of each Theater Command’s PLAAF and PLANAF order of battle. It is through this structured approach that Rupprecht meets his goal of drawing upon Modern Chinese Warplanes and answering the following question: If conflict were to occur at any of the flashpoints, what People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and PLA Naval Air Force (PLANAF) units and platforms are likely to be involved?

Over the last two to three decades China’s entire military force has undergone a rapid and unprecedented military modernization campaign designed to transform it into a regionally-dominant and globally-significant force. To further tie his two books together however, Rupprecht would be remiss to not include an update of what has transpired within and across the PLA between the books’ publication dates (2012 and 2016, respectively) in the introductory section of Flashpoint China, specifically how PLA reforms and the subsequent establishment of the five Theater Commands have affected the PLAAF and PLANAF. Additionally, Rupprecht briefly describes concepts such as China’s “active defense strategy” and “anti-access /aerial denial (A2/AD)” (what the Chinese refer to as “counter-intervention”) capabilities. Counter-intervention represents how China plans to “deny the U.S. [or other foreign] military the ability to operate in China’s littoral waters in case of a crisis.”3 Collectively, these organizational, doctrinal, and operational changes should weigh heavily in a book of this nature yet Rupprecht does not fully incorporate their significance in his work. To do this, the author would need to answer the following question: How would PLAAF and PLANAF platforms and capabilities likely be employed to prevent U.S. or other regional forces from intervening in a conflict at any of the flashpoints?

Some of these geographical areas and issues carry a higher military priority for China. According to the U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) in its 2017 Annual Report to Congress, “Taiwan remains the PLA’s main “strategic direction,” one of the geographic areas the leadership identifies as endowed with strategic importance [and represents a “core interest” of China]. Other focus areas include the East China Sea [ECS], the South China Sea [SCS], and China’s borders with India and North Korea.”4 And as the strategic importance of a geographical area increases for China so does its allocation of PLA assets.

For example, the richness and variety of the geopolitical concerns involving the countries presented in Chapter Two of Flashpoint China (Japan, Russia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), and South Korea), provide significant examples of historical, current, and potential military conflict for China; however, in Chapter Two Rupprecht doesn’t reflect on the order of strategic priority and therefore the military significance of the Northern and Central Theater Commands. Instead, Chapter Two opens with a very brief paragraph regarding Mongolia, thereby dampening the impact of the chapter’s “flashpoint” narrative.

Additionally, the sovereignty dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the ECS dominates the military significance of China’s foreign policy vis-à-vis Japan; however, Rupprecht merely allocates a single sentence to the situation: “The dispute over the Senkaku Islands – known as the Diaoyu Islands in China – is meanwhile a matter of heated rhetoric and near-open hostility.”5 Since the historical dispute took a dramatic leap forward in April 2012 following the Japanese purchase of three of the eight islets from their private owner, the PLA’s Eastern Theater Command has assumed primary responsibility for this flashpoint area. Unfortunately, Chapter Two mistakenly assigns PLA responsibility for China’s ongoing dilemma with Japan in the ECS to the Northern and Central Theater Commands: “The PLA subordinates responsibility for Japan and the Korean peninsula to the Northern Theater Command and to the Central Theater Command.”6 When the purchase was made public, the PLA immediately began regularly deploying maritime and airborne patrols from Eastern Theater Command bases into the ECS to assert jurisdiction and sovereignty over the islands. Additionally, as Rupprecht alludes to on page 25, in November 2013, China declared the establishment of its first air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the ECS which included the area over the disputed islands. Subsequently, both the PLAAF and PLANAF established routine airborne patrol patterns and the use of ECS airspace and the straits of the Ryukyu Islands to conduct long-range, integrated strike training with PLA Navy (PLAN) assets in the western Philippine Sea.

Additionally in Chapter Two, Rupprecht aptly describes the history of Sino-Russian relations: “For years, relations between China and Russia have been described as a ‘tightrope walk’, and have frequently oscillated between close friendship and war.”7 However, the author fails to capture the significance of the military connection between Russia and China, especially as it relates to Rupprecht’s stated theme for this book, for China’s military modernization arguably started with mass acquisitions of Russian military technologies in the early 1990s. Over the ensuing decades, China embarked on a widespread effort to acquire Russian military technologies, reverse-engineer that technology, and then indigenously mass-produce similar technologies adapted to Chinese specifications. That period however may be rapidly coming to a close as many China analysts assess that China has now transitioned from a Russian technology-dependent force to a truly indigenous production force. In fact, China’s most recent procurement of Russia’s technologically-advanced Su-35 FLANKER S fighter aircraft and S-400 strategic-level surface-to-air missile (SAM) system, touched on by Rupprecht on page 18, may be the last significant items on China’s military hardware shopping list.

Another example is found in Chapter Three which Rupprecht opens by stating, “The issue of Taiwan is a very special one for the PRC, and certainly the top priority in regard to the PLA’s modernization drive. This is clearly indicated by the official order of protocol, which lists the responsible Eastern Theater Command first.”8 Although the Eastern Theater may have primary responsibility for the Taiwan issue, the extraordinary political, strategic, and economic significance of the Taiwan dispute represents a “core interest” of China. This fact cannot be overstated. The entire essence of Chinese military modernization efforts over the recent decades have been in direct support of the possible requirement to take back Taiwan by force should alternative means of reunification prove fruitless. As Chinese Communist Party legitimacy would ride on the success or failure of a PLA campaign to “liberate” Taiwan, an effort of this magnitude would involve PLAAF and PLANAF assets from multiple Theater Commands, something Rupprecht’s narrative and order-of-battle charts do not capture.

The geography, the respective sovereignty claims, and the strategic and operational scope of each Theater Command’s responsibilities matter greatly with respect to China and its ambitions. Each chapter ends with a wonderful map that provides a highly informative, geographical illustration of each respective theater. The geographical impact of each chapter’s flashpoints may be better served however by moving each chapter’s map to the beginning of the chapters rather than the end.

Rupprecht’s best work is reflected in Chapter Four. China’s sovereignty claims and the controversial Chinese land reclamation and infrastructure construction activity in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea (SCS) presented in Chapter Four are definitely the most contentious issues facing the Southern Theater Command. And here Rupprecht does not disappoint. The author allocates numerous pages to both describe and illustrate the significance of the SCS dispute to China, its regional neighbors, and the U.S. Just as in Modern Chinese Warplanes, Rupprecht has included spectacular, colored photographs of various Chinese aircraft into Flashpoint China. Various PLAAF and PLANAF fighters, reconnaissance and transport aircraft, along with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) are presented in wonderful detail throughout the book. Chapter Four however is especially unique for its inclusion of vivid photographs of China’s land reclamation and infrastructure construction activity in the Spratly Islands.

How Chinese, U.S., and regional neighbors approach this issue politically, diplomatically, and militarily carries significant strategic, operational, and tactical implications. History has proven how a single tactical event in the region can carry immediate and substantial strategic implications. For example, the infamous EP-3 incident of 2001 provides just one example of how tactical miscommunication and miscalculation can have significant strategic implications.9 These type of airborne interactions continue on a regular basis as U.S. reconnaissance aircraft operate in international airspace over the SCS. Chinese fighter aircraft routinely intercept the U.S. aircraft, sometimes operating outside the assessed bounds of safe airmanship. Japanese fighters also come into regular contact with Chinese aircraft, regularly scrambling to check Chinese airspace incursions over the ECS and through the Ryukyu Straits. These tactical events often receive attention from the government and military leaders of the respective countries and occasionally result in public demarches.

In a book of this nature, each SCS claimant country deserves its own dedicated section as China’s rise has forced each country’s government to reassess their national security and military means with some countries making substantial increases in their military expenditures. For example, Vietnam is “in the process of addressing its limitations with respect to combating modern threat scenarios with its existing obsolete equipment, and has embarked on military modernization plans over the last few years.”10 Additionally, the 02 May – 15 August 2014 Hai Yeng Shi You 981 oil rig standoff (also referred to as the “CNOOC-981 incident”) provides a real-world event which not only illustrated the contentiousness of the SCS claims between China and Vietnam, but also revealed an operational reaction from the PLA, with specific operational responses from both the PLAAF and PLANAF.11

Finally, the most impactful flashpoint for China in the Western Theater, presented in Chapter Five, regards India. Typically the issue between the two countries revolves around unresolved border disputes; however, much to India’s chagrin, China also continues to advance its military-to-military relationship with India’s rival, Pakistan. This is especially relevant for Rupprecht’s efforts within Flashpoint China as Pakistan’s Air Force and China’s PLAAF conducted the sixth consecutive iteration of the annual “Shaheen” series of joint exercises in 2017. Since its inception in 2011, the Shaheen exercise series has consistently grown in complexity and scope, incorporating a wider variety of PLAAF aircraft and platforms such as multi-role fighters, fighter-bombers, airborne warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft, and surface-to-air missile crews and radar operators.

Conclusion

In Flashpoint China Andreas Rupprecht ambitiously attempts to couple the highly complex geopolitical environment surrounding modern day China with the PLAAF and PLANAF’s ever-evolving order of battle and force projection capabilities – an assignment with which even the most renowned scholars would struggle, especially within the allotment of so few pages. Via the well-structured narrative and fabulous photographs, Flashpoint China goes a long way in tackling the question of what PLAAF and PLANAF assets could China bring to the fight should a military conflict occur at any of the presented flashpoints. Readers however would have certainly enjoyed reading the author’s assessment of how might the PLA use its air power in support of Chinese military intervention into these contentious hotbeds. But this may have to wait for another day. Still, if brevity of space and time were the only options available to the author, then Flashpoint China can certainly prove useful as is. However, with even some minor content and structural improvements, the book could prove irreplaceable.

LCDR David Barr is a career intelligence officer and currently serves as instructor with the National Intelligence University’s College of Strategic Intelligence. All statements of facts, analysis, or opinion are the author’s and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Intelligence University, the Department of Defense or any of its components, or the U.S. government.

References

1. Buckley, Chris. “Xi Jinping Opens China’s Party Congress, His Hold Tighter Than Ever”; The New York Times; 17 October 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/17/world/asia/xi-jinping-communist-party-china.html

2. Rupprecht, Andreas. Flashpoint China, Chinese Air Power and Regional Security. Houston: Harpia Publishing, 2016. p. 9.

3. Ibid. p. 15.

4. OSD. Annual Report to Congress: “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017,” OSD, (Annual Report, OSD 2017)

5. Rupprecht, Andreas. Flashpoint China, Chinese Air Power and Regional Security. Houston: Harpia Publishing, 2016. p. 21.

6. Ibid. p. 21.

7. Ibid. P. 17.

8. Ibid. p. 31.

9. Rosenthal, Elisabeth. “U.S. Plane in China After It Collides with Chinese Jet”; The New York Times; 02 April 2001. http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/02/world/us-plane-in-china-after-it-collides-with-chinese-jet.html

10. Wood, Laura. “Future of the Vietnam Defense Industry to 2022 – Market Attractiveness, Competitive Landscape and Forecasts – Research and Markets”. Business Wire; 04 October 2017. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20171004006043/en/Future-Vietnam-Defense-Industry-2022—Market

11. Thayer, Carl. “4 Reasons China Removed Oil Rig HYSY-981 Sooner Than Planned”. The Diplomat; 22 July 2014. https://thediplomat.com/2014/07/4-reasons-china-removed-oil-rig-hysy-981-sooner-than-planned/

Featured Image: Two JH-7 fighter bombers attached to an aviation brigade of the air force under the PLA Western Theater Command taxi abreast on the runway before takeoff for a sortie near the Tianshan Mountains in late March, 2018. (eng.chinamil.com.cn/Photo by Wang Xiaofei)