CIMSEC

Announcements

CIMSEC February Recap by Dmitry Filipoff

Call for Articles: Naval HA/DR Topic Week by Dmitry Filipoff

CFAR 2016: And the Winners are… by Scott Cheney-Peters

Naval HA/DR Topic Week Kicks Off on CIMSEC by Dmitry Filipoff

Naval HA/DR Topic Week

Other Than War: HA/DR and Geopolitics by Joshua Tallis

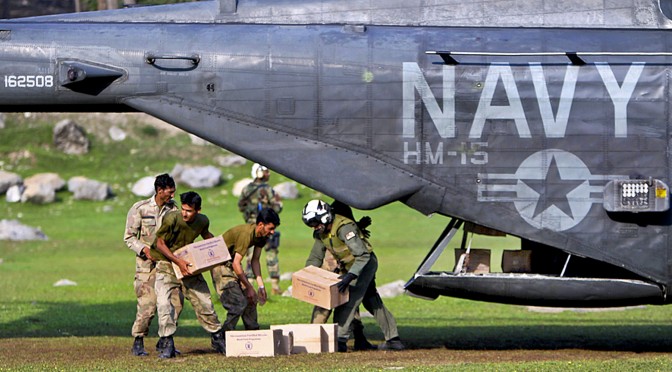

Positioning Naval HA/DR in India’s Image Making by Vidya Sagar Reddy

How Lessons from HA/DR Can Prepare Naval Forces for Combat by Greg Smith

Applying Interagency Concepts from Domestic Disaster Response to Foreign HA/DR by Robert C. Rasmussen

Aligning HA/DR Mission Parameters with US Navy Maritime Strategy by CAPT John C. Devlin (ret.) and CDR John J. Devlin

A Proactive Approach to Deploying Naval Assets in Support of HA/DR Missions by Marjorie Greene

Enabling More Effective Naval Integration into Humanitarian Responses by David Polatty

The Challenges of Coming Together in a Crisis by David Broyles

Flattops Of Mercy by LCDR Josh Heivly

The Legacy of the 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami On U.S. Maritime Strategy by CDR Andrea H. Cameron

Podcasts

Real Time Strategy 5: Metal Solid V: The Phantom Pain hosted by Bret Perry

Sea Control 111: Vietnam Era Drones (QH-50) hosted by Matt Hipple

Sea Control 112: Australia’s 2016 Defence White Paper hosted by Natalie Sambhi

Sea Control 113: Abraham Lincoln’s Self-Education hosted by Matt Merighi

Interviews

Tom Ricks on Writing, Reading, and Military Innovation by Christopher Nelson

CIMSEC Interviews Larry Bond and Chris Carlson on Their New Novel, Wargaming, and More by Bret Perry

Member Round Up

February Members’ Roundup Part One by Sam Cohen

February Members’ Roundup Part Two by Sam Cohen

Member’s Roundup: March 2016 Part One by Sam Cohen

Events

14-18 March 2016 Events of Interest by Emil Maine

21-27 March 2016 Events of Interest by Emil Maine

28 March- 3 April 2016 Events of Interest by Emil Maine

Naval Affairs

The Aegis Warship: Joint Force Linchpin for IAMD and Access Control by John F. Morton

crossposted from NDU Joint Forces Quarterly

Series: 21st Century Maritime Operations under Cyber-Electromagnetic Operations by Jon Solomon

crossposted from Information Dissemination

Part One (Feb.)

Part Two (Feb.)

Part Three

Finale

Integrated Masts – The Next Generation Design for Naval Masts by Commander (Dr.) Nitin Agarwala

crossposted from Defencyclopedia

“A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority” – A Coastie’s View by Chuck Hill

‘A Fiscal Pearl Harbor’ by Dr. Eric J. Labs

crossposted from U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings

Athena Project San Diego Innovation Jam Roundup by Dave Nobles

crossposted from the Athena Project

Asia-Pacific

A Comparative View of the Ancient and 21st Century Maritime Silk Roads by Mohid Iftikhar and Dr. Faizullah Abbasi

South Sea Fleet: The Emerging ‘Lynchpin’ of China’s Naval Power Projection in the Indo-Pacific by Gurpreet S. Khurana

crossposted from the National Maritime Foundation

The Nature of the PRC’s National Defense and Military Reform by Ching Chang

Singapore’s Fleet Modernization: Slow and Steady? by Paul Pryce

America’s Dilemma in Avoiding Confrontation in the East Asian Littoral by David Hervey

Transparency as Strategy: The Maritime Security Initiative and the South China Sea by Dr. Van Jackson, Dr. Mira Rapp-Hooper, Paul Scharre, Harry Krejsa, and Jeff Chism

China’s Arctic Engagements: Differentiating from Reality and Apprehension by Adam MacDonald

crossposted from Conference for Defense Associations Institute

Africa

West African Navies Coming of Age? by Dirk Steffen

Middle East

Pakistan’s Navy: A Quick Look by Alex Calvo

Europe

A Call for an EU Auxiliary Navy – Under German Leadership by Dr. Sebastian Bruns

Western Hemisphere

Opinion: The Uses of the U.S. Navy’s Fourth Fleet by W. Alejandro Sanchez

Undersea

An Underwater Cloud by Alix Willimez

Reviews

Book Review: Piracy and Armed Robbery at Sea by Alex Calvo

Red Phoenix Burning by Bret Perry

Practise To Deceive: Learning Curves of Military Deception Planners by LT Jake Bebber