By Captain John P. Cordle, USN (Ret) and K. Denise Rucker Krepp

Part Two

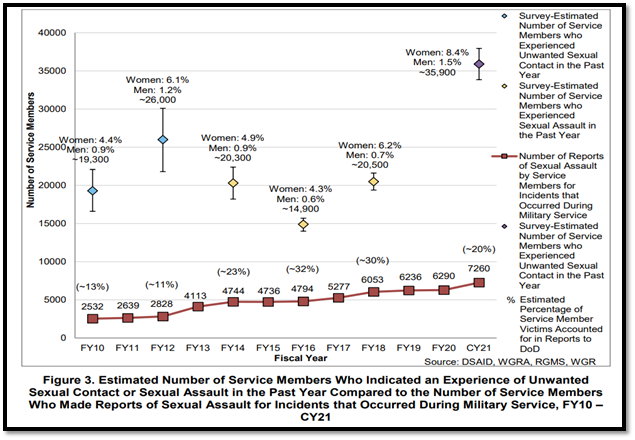

In Part One we shared our experience and gave some interpretations of the data.* In this part we will finish that discussion and proceed to a set of recommendations. In the spirit of the discussion, it is important to understand that the trends are all heading in the wrong direction, indicating that policy and procedure changes are not enough. A culture change is required, starting at the unit level, if these trends are to be reversed. The following graph shows the magnitude of the problem, and the disturbing trend:

5. Victims Bear a Heavy Burden

The IRC spoke with hundreds of survivors of sexual assault during the 90-Day review. One-on-one interviews and panel discussions brought to light the substantial burdens placed on victims as they navigated the military justice and health systems. Many survivors with whom the IRC spoke had dreamt their entire lives of a career in the military; in fact, they loved being in the military and did not want to leave, even after experiencing sexual assault or sexual harassment. But because their experience in the aftermath of the assault was handled so ineptly or met with hostility and retaliation, many felt they had no choice but to separate.

John: This echoes the case of my friend, who resigned from the Navy after nearly 10 years with the feeling – related to me directly – that she had no faith the system would change. The idea of psychological safety of the victim is huge and must be considered by leaders throughout the process. Again the DoD report is quite damning, showing that retribution and retaliation were found in 30 percent of cases – that means that someone who makes a report has a one-in-three chance of being retaliated against by the command or the alleged aggressor. I would never want my leadership to be characterized as “inept” – but the report found enough evidence to include this finding. Again, get out the mirror.

Denise: I have worked with both male and female sexual assault victims, including military and civilian. Service Academy students are nominated by Congressmembers to attend highly selective federal institutions. They have generally achieved high marks and excelled academically in high school to compete for the nomination. Most also excel in sports and extra-curricular activities to be competitive. They and their parents fill out mountains of paperwork and then they finally arrive at the school, full of dreams. Then reality sets in; I have seen their dreams of 20 years of service dashed by sexual assault. I have seen the tormented crying eyes of mothers and the rage-filled eyes of fathers, many of whom are alumni of the same institution.

When the military fails to help MST victims, the services also fail their parents. The failure is remembered and retold at family gatherings around the country. It is also told in videos, including the one that I watched at the new movie museum in Los Angeles. Every day, thousands of museum visitors learn about how the military failed to protect those who fought so hard to wear the uniform. If we want to look at why the military is having a recruiting problem, one place to start is the negative recruiting by those who recall a SASH event during their service – and tell their story. People do not want to join or stay in an organization where they are not respected.

6. Critical Deficiencies in the Workforce

The workforce dedicated to Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) is not adequately structured and resourced to do this important work. Many failures in prevention and response can be attributed to inexperienced lawyers and investigators, collateral-duty (part-time) SAPR victim advocates, and the near total lack of prevention specialists. These failures are not the fault of these personnel, but rather of a structure that de-emphasizes specialization and experience, which are necessary to address the complexities of sexual assault cases and the needs of victims.

John: You get what you pay for. Again there have been major steps taken in the past year to address these deficiencies, but if this is not the topic of a significant “Get Real Get Better” moment in the Pentagon then none such exists. One service member whom the author is mentoring received a letter at 180 days explaining that due to a backlog, her case – which was supposed to be adjudicated within 90 days – would take at least another 120 days – meanwhile she works at the same command with the alleged perpetrator, feeling that system has failed her – because it has. From collateral duty officers and chiefs with little training or motivation, to the oft-quoted dearth of mental health resources across the military, there is much to be done here. But what about the unit level? I submit that it is not OK to wait for the Navy to train thousands of counselors over the next few years. If you are in command today, take a personal interest in your staff and make sure that they have both the ability, the time, and the training to do the tough job of a sexual harassment (SH) or SAPR representative. Make sure that the available resources at the Fleet and Family Service Center are part of Command indoctrination, the command Facebook page, family support groups, and the sponsor program.

Denise: The critical deficiency I witnessed as a federal agency chief counsel and as a locally elected official was the lack of robust investigations and prosecutions. Prosecutors were not trained to prosecute the cases, were overworked and inexperienced, and found it easier to drop the case, claiming lack of evidence, than to do the work of studying the evidence and asking questions.

7. Outdated Gender and Social Norms Persist Across the Force

Although the military has become increasingly diverse, women make up less than 18 percent of the total force.4 With these dynamics, many women who serve report being treated differently than their male counterparts. In the IRC’s discussions with enlisted personnel, many Service women described feeling singled out or the subject of near daily sexist comments, as one of few women in their units.

John: Did you know that there are still several Navy ships with no female enlisted crew members? A recent photo of the senior Surface Warfare Flag Officers includes only two female Admirals. Diversity breeds inclusion – and a lack thereof does the opposite. The USMC lags the other services in female percentage by a significant margin, and yet are the apparent source of resistance to the Task Force One Navy recommendation to include RESPECT as a fourth core value. Unit leaders must look at their command through the eyes of the least represented and act accordingly. That said, it is also important to bear in mind that SH and SA are not restricted to a single gender and males can be targets as well, bringing a separate set of stigma and consequences for the victim, who may be labeled with a sexual orientation that is not their own due to the nature of the incident.

Denise: I served on active duty from 1992-2002. I left active duty because it was crystal clear at that time that I would not make Captain and Admiral. I was smart enough to become a senior leader but I was not going to be given the jobs that would make me eligible for them. I made this determination after talking with my father, a USMA grad who made 06 by the age of 40. He had seen combat in Vietnam and was a Ranger.

My generation of women were not eligible for career-enhancing combat jobs, so many of us left the service, which is why there are not that many female Admirals today – it literally takes a generation to change that. Women continued to leave in the 2000s because again, the jobs were not open to us and if they were, we were subjected to comments by senior leaders like “don’t go getting pregnant on me.” (that is sexual harassment, by the way.) There were also other obstacles like unwavering weight standards that had to be met after having children, hairstyles that caused our hair to fall out, and horrible uniform designs…Problems our male counterparts never had to overcome. But looming large was the ever-present threat of being sexually harassed – or worse – and having it be ignored.

8. Little is Known about Perpetration

The most effective way to stop sexual harassment and sexual assault is to prevent perpetration. However, the Department lacks sufficient data to make evidence-based decisions in this domain. As a result, the impact of prevention activities in military communities, particularly activities aimed at reducing perpetration, remains relatively unknown.

John: The most important role of the unit commander here is to properly investigate and report the data in a timely manner. One service member shared being told to “think twice” about making a report because “it would make the command look bad” – by the command equal opportunity counselor! This should never happen. Face the facts, do not shy away, and make the required reports, regardless of the consequences – it is the right thing to do. While training may inhibit sexual harassment through better education and intervention, sexual assault is a crime, and all the training in the world is not going to stop someone who is already so inclined. But proper training to recognize the signs of a bad trend can lead to more intervention and thus, hopefully, to prevention or at least prosecution. Sexual predators have no place in the military and should be excoriated as efficiently as possible.

Denise: The best way to stop SASH is to prosecute existing cases and publicize the outcomes. Publicize how offenders are sent to prison. Publicize the loss of retirement benefits. Publicize all cases regardless of rank. Make it clear that everyone is held to the same standard.

Additionally, every year Department of Defense employees are required to take sexual assault and sexual harassment training. My recommendation is to include information in the training on the number of reports received each year, the number of individuals prosecuted each year for sexual assault and the number of individuals successfully court martialed for sexual assault.

We usually end an article with a list of recommendations, but since we both agree with all of the IRC findings, we will simply list them here (below) while encouraging the reader to find and read the original report. Many of them are at the Big Navy level – but we would encourage the reader to point out to their leadership where these actions are not having the desired effect or fast enough – and to be a demanding customer.

Key Recommendations:

-

- Ensure Service members who experience sexual harassment have access to support services and care.

- Professionalize, strengthen, and resource the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response workforce across the enterprise.

- Improve the military’s response to domestic violence—which is inherently tied to sexual assault.

- Improve data collection, research, and reporting on sexual harassment and sexual assault to better reflect the experiences of Service members from marginalized populations—including LGBTQ+ Service members, and racial and ethnic minorities.

- Establish the DoD roles of the Senior Policy Advisor for Special Victims, and the DoD Special Victim Advocate.

Accountability

-

- Create the Office of the Special Victim Prosecutor in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and shift legal decisions about prosecution of special victim cases out of the chain of command.

- Provide independent trained investigators for sexual harassment and mandatory initiation of involuntary separation for all substantiated complaints.

- Offer judge ordered military protective orders for victims of sexual assault and related offenses, enabling enforcement by civilian authorities.

Prevention

-

- Equip all leaders with prevention competencies and evaluate their performance.

- Establish a dedicated primary prevention workforce.

- Create a state-of-the-art prevention research capability in DoD.

Climate and Culture

-

- Codify in DoD policy and direct the development of metrics related to sexual harassment and sexual assault as part of readiness tracking and reporting.

- Use qualitative data to select, develop, and evaluate the right leaders for Command positions.

- Apply an internal focus on sexual violence across the force in DoD implementation of the 2017 National Women, Peace, and Security Act.

- Fully execute on the principle that addressing sexual harassment and sexual assault in the 21st century requires engaging with the cyber domain.

Victim Care and Support

-

- Optimize victim care and support by establishing a full-time victim advocacy workforce outside of the command reporting structure.

- Expand victim service options for survivors by establishing and expanding existing partnerships with civilian community services and other Federal agencies.

- Center the survivor by maximizing their preferences in cases of expedited transfer, restricted reporting, and time off for recovery from sexual assault.

That concludes the recommendations from the report. But it cannot end there. Only those in uniform can reverse this trend. That is our call to action.

Looking in the Mirror

One senior individual who read the draft of this article shared the idea that “nothing here is new,” citing Tailhook, Marines United, and other so-called “wake up calls” going back decades. Reports were filed, actions taken, briefs prepared – and yet here we are. Will it be different this time? Only we, the deck-plate leaders, can answer that question. In the end, we all want a workplace where we feel comfortable doing our jobs, and one where we would advise our children to join this organization. At a recent diversity symposium, a young Marine asked a retired General on the leadership panel “If I were your daughter – would you advise me to join the Military today?” There was a long and suspenseful pause before the answer came – which I will keep private – but the fact that the answer was not an immediate and resounding “yes!” speaks volumes. If we accept this condition then perhaps we are the problem. If we tolerate the occasional inappropriate comment, the sexist joke, the unwanted touch – we become complicit. Is it easier to just look away? Sure. But that is not what leaders do – good ones, anyway!

We encourage all leaders in the Navy and Marine Corps to read and truly digest both the 2021 DoD Sexual Harassment report and the IRC report. If you teach at a Navy schoolhouse, especially a leadership course, add these to the required reading list. You will be astounded and disappointed to learn that the trends are in the wrong direction almost across the board. These two documents are both authoritative and stunning – and yet many have not read them in the first place. Navy leaders at the upper levels are taking action, but as someone once posted on a USNI Blog feed a few years ago, “culture change does not happen by instruction or edict, but by the actions of each individual throughout the organization, on the deck plates, on a daily basis.” We firmly believe this to be true.

This is not just a CNO or SECNAV problem – they are taking action. It is your problem and our problem. And only we can solve it.

Have your own #MeToo moment.

John Cordle is a retired Navy Captain who commanded two warships, was awarded the Navy League John Paul Jones Award for Inspirational Leadership, and the 2019 US Naval Institute PROCEEDINGS Author of the Year.

K. Denise Rucker Krepp spent several years on active duty in the U. S. Coast Guard, graduated from the Naval War College, and served as Chief Counsel for the U.S Maritime Administration. Krepp also served as a locally elected Washington, DC official and Hill staffer. She is a longtime advocate for the rights of sexual assault and harassment victims.

*Correction: the Independent Review Committee was ordered by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, not SECNAV as we stated in Part 1.

Featured image: A Marine practices in front of the USS Green Bay (U.S. Navy photo by Markus Castaneda.)