By Gonzalo Vázquez

Introduction

With the return of great power competition and the prospects for a highly-contested maritime space in the Euro-Atlantic area, NATO will be called to play a more active role at sea to preserve stability and freedom of navigation. The protection of maritime commerce and critical undersea infrastructure, key drivers of the global economy, are now coupled with the need to strengthen naval deterrence and high-end warfighting capabilities. Balancing both ends of the spectrum, however, is likely to be very demanding under current fiscal constraints in allied defense spending. Allied governments and their navies will have to maximize their available resources and put them to use in the most efficient way possible, especially with maritime security-related missions and operations.

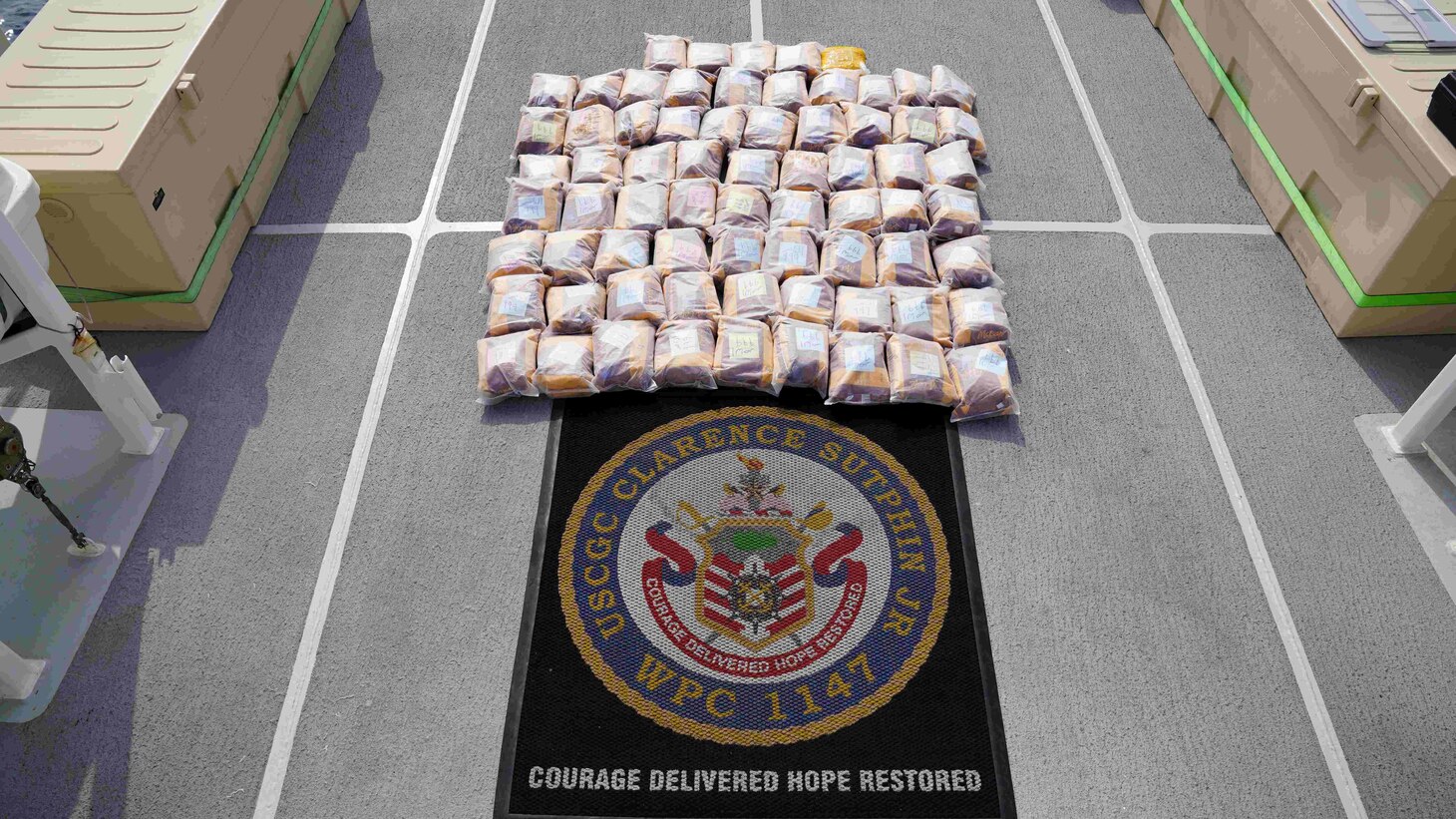

Unlike many of its NATO allies, Spain does not currently have a Coast Guard service to protect its waters. Rather, it has a number of different services with different competencies which are under the responsibility of six different national ministries. While these services provide a constant presence across Spanish maritime territories, they lack a unified command and are often ill-equipped to perform their duties effectively. Last year’s tragic episode in Barbate, Cadiz, which saw the death of two Guardia Civil officers who were rammed by a drug contraband craft while attempting to intercept it, is a case in point.

Following the example of many of its European and American allies in NATO, it is worth exploring the potential establishment of a Spanish Coast Guard that merges all these existing services under a single, professional service with a unified and clearly defined command structure. While the process would undoubtedly face considerable bureaucratic and economic obstacles in the short to medium term, it would be highly beneficial in the long-term, providing NATO’s southern flank with a stronger constabulary presence – particularly around the busy approaches of the strategic Strait of Gibraltar.

NATO’s Maritime Southern Flank

After decades of a predominantly continental orientation of the Alliance’s strategic calculus and the war in Ukraine still keeping most of the Alliance’s attention on its eastern flank, the return of great power competition has brought about old and new threats to maritime stability around NATO’s maritime flanks. The Baltic Sea has seen a series of attacks against critical undersea infrastructure which have prompted an increase in maritime vigilance assets. Despite receiving less attention, the security landscape in the Mediterranean region is also undergoing a significant transformation.

As asserted by Jeremy Stöhs and Sebastian Bruns, “with the return of great-power competition and the corresponding activities of revisionist actors in the wider Mediterranean region, the Mediterranean has come roaring back as a contested body of water.” As a consequence of this, “Western decision-makers should revisit their approaches to the use of naval power in the region.” From among the main naval powers in the region, Italy has shown a commendable commitment to strengthen its naval power and maritime presence all across its “enlarged Mediterranean,” as proven by the ambitious plans announced for the Marina Militare and its successful deployments to protect merchant shipping in the Red Sea.

Among the most pressing security challenges for Spanish and NATO’s maritime security are the well-known and much-needed protection of critical undersea infrastructure, and especially in the south, the prevention of irregular migration flows, and drugs and weapons smuggling. There is also the relatively recent threat posed by the so-called Russian Dark Fleet. These “vessels engaged in illegal operations to avoid sanctions by seeking to skirt various aspects of maritime regulation and provisions for insurance,” and operate in a way that “the complexity of both the ownership and operator structures is meant deliberately to obscure and confuse.” Spain is highly vulnerable to environmental disasters given the high traffic of dark fleet vessels along its coasts, as several Spanish analysts have been warning about for years.

The need for a regeneration of allied naval power in its southern backyard demands a careful assessment of existing structures and bodies in charge of providing the necessary constabulary services and deterrent posture. One such example is the case of Spain, who is one of the main naval powers in the Mediterranean and an active contributor to the Alliance’s Standing Maritime Groups. Beyond the challenges that the Armada faces today, including the need for a bigger submarine fleet, the organization of Spain’s highly decentralized constabulary presence remains an enduring headache for many within its maritime community.

Spain’s Maritime Constabulary Conundrum

A quick glance at Spain’s position on the global map reveals its strong geographic inclination to the sea. Extensive coasts both in the Mediterranean (including the Balearic Islands), the Cantabric Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean (including the Canary Islands), as well as its position as the guardian of the Gibraltar Strait make it one of the most maritime nations in all of Europe. Yet as history reveals, Spanish political elites have traditionally neglected such predisposition in favor of a highly contradictory continental mindset, thus preventing them from embracing all the opportunities the sea could provide to their national prosperity. Simply put, Madrid has failed to fulfill one of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s core constituents of sea power – the character of government.

One of the main aspects in which such neglect manifests itself in the present day is the convoluted organization of its many maritime services. Spain’s constabulary presence around its territorial waters and EEZ comprises a variety of actors and institutions, with overlapping and decentralized tasks and functions. This leads to a waste of valuable efforts and resources which could otherwise be managed in a much more efficient and effective way – particularly at a time when the maritime services all across Europe are especially demanded to defend their existence and need for funding vis à vis a continentally-minded political leadership.

Up until 1986, maritime security responsibilities had been undertaken by the Customs Surveillance Service (Servicio de Vigilancia Aduanera), focusing on maritime interdiction operations, and the Armada fulfilling both its military responsibilities as well as any other necessary tasks as demanded by any of the Government’s Ministries. In 1986, the Government passed the State’s Security Forces and Corps Bill (Ley de Cuerpos y Fuerzas de Seguridad del Estado), which resulted in the establishment of additional institutions involved in maritime constabulary operations. The first two of those were the Maritime Service (SEMAR) of the Guardia Civil, and the Maritime Security and Rescue Service (SASEMAR), followed by others that include the Spanish Oceanography Institute (IEO), the Marine Social Institute (ISM), or the Marine Fisheries General Secretariat (SEGEPESCA).

As of today, the Navy is in charge of surveillance and security over all maritime spaces of Spanish sovereignty, from the coast to the limit of the EEZ, from a national security perspective. The Customs Surveillance Service retains responsibilities exclusively for customs and fiscal matters within the territorial seas, while the Guardia Civil Maritime Service does the same with judicial, fiscal, and administrative matters also within the territorial seas.

Thus, these and several other bodies with similar tasks and responsibilities – all equipped with their own small fleets of vessels, aircraft ,and independent command and control systems – has gradually led to the establishment of a hydra-like maritime constabulary presence. It is inefficient and uneconomical given their overlapping responsibilities.

Altogether, as argued by LCDR (ret.) Fernando Novoa, each body having its own competences, culture, responsibilities, training, and procedures leads to a true amalgam of types of vessels and aircraft models, adding to the overwhelming lack of standardization. This results in expensive and unnecessary maintenance, logistical, and operational costs.

A Spanish Coast Guard

In light of these problems, and building on the existing debate within Spanish maritime and naval circles, Spain should explore the creation of a Coast Guard with a similar model to that of the United States, Norway or Italy. There is a need for a professional service that works with the Navy while assuming all civil and constabulary functions. It would remove the existing conundrum and solve the existing duplicities among so many different institutions.

The idea is not new by any means. On the contrary, it has been raised on many occasions within Spanish maritime debates. But the argument needs to be expanded to include a discussion of the benefits that the establishment of such an institution could have for NATO’s constabulary presence on its southern flank.

Captain (ret.) Francisco Romero has been another defender of the need for “a Coast Guard entirely responsible for all surveillance and national security tasks, judicial, fiscal, administrative, customs and contraband surveillance all across Spanish territorial seas.” In his view, such an institution should be placed under the operational command of the Navy, looking to the U.S. Coast Guard as a model to imitate, while also coordinating its activities with the Air Force’s Maritime Patrol assets and the Navy’s own offshore patrol vessels and associated platforms.

The establishment of a Spanish Coast Guard would ideally have to merge into a single service all (or most of) the existing services, with their assets and functions under the unified command of a single institution independent from the Navy and answerable to the Defense Chief of Staff and the Ministry of Defense (as proposed by LCDR Novoa). Others have even considered the establishment of a single maritime border constabulary force under the Ministry of Interior. As can be logically inferred, in case of conflict, the smaller the number of services that need to be coordinated to support the Navy, the better.

The successful establishment of such service, however, would face significant administrative and bureaucratic boundaries given the variety of ministries and actors involved in the process. The first and perhaps most important conundrum is which government actor should be ultimately responsible for it. As mentioned, both the Ministries of Defense and Interior are the most likely candidates. The second question is which assets should be pooled together to constitute the new service. The different proposals made over the years range from merging only a few of the existing institutions while leaving others with limited competencies, to merging all of them into one single service that works with the Navy (either under its command or separately). In case of the latter, the Navy could potentially provide the manpower to help build the expertise of personnel. Perhaps the first step to take could involve a reassessment of the current services to eliminate their overlapping responsibilities before merging them into a new, single service.

As lengthy and costly the process may be, establishing a Spanish Coast Guard would allow for higher interoperability among allied coast guard services on the NATO’s southern flank. This, in turn, would benefit the alliance by supporting constabulary operations such as Operation Active Endeavour (OAE). Since its establishment in 2016 as the successor of Operation Sea Guardian, OAE has provided a significant presence along the Alliance’s Southern Flank. Its main missions include supporting maritime situational awareness, upholding freedom of navigation, conducting interdiction tasks, maritime counter-terrorism, contributing to capacity building, countering proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and protecting critical infrastructure. The operation relies on the support of Allied navies, which provide it with surface and submarine units, maritime patrol aircraft, and airborne early warning aircraft.

In light of the pressing demand for additional naval capabilities and the need to devote larger warships (frigates and destroyers) to high-end operations rather than purely maritime security operations, southern NATO coast guards could be potentially involved in supporting operations such as OAE to free up military units for high-end tasking. Even if not integrated with these operations, the sole presence of European coast guards across the Mediterranean Sea and Strait of Gibraltar would still provide additional maritime presence, and a more structured one. Most of the existing challenges at sea today can be mitigated to some extent by means of stronger maritime domain awareness, something for which coast guards are more than adequately suited.

Altogether, NATO’s maritime threats and challenges have showcased the need for increase awareness and naval presence, while assuming that budgetary constraints will remain a major hurdle in the quest to expand the size of navies – both in terms of assets and manpower. Allied governments and military staffs should strive the find the most effective ways to maximize the employment of their available assets.

Conclusion

While the case of Spanish constabulary presence at sea is a very concrete one when framed within the broader NATO context, it remains a telling example for the complex challenges the Alliance faces today. At a time when European nations are being called to play a bigger and more relevant role in the protection of Europe’s maritime flanks, in the midst of significant budgetary constraints, allies must strive to maximize the efficacy and efficiency of their maritime institutions and avoid any unnecessary duplication of effort.

The last decades have witnessed the emergence of a wide plethora of asymmetric threats within their waters, including the continuous attacks against critical undersea infrastructure, the ongoing irregular human and drug trafficking from the African continent, or the looming risk of an environmental disaster posed by Russia’s dark fleet. These threats overlap with the enduring need for high-end naval capabilities as showcased by the Red Sea crisis.

Altogether, European maritime and naval services will have to step up and take on a larger responsibility as the United States continues shifting its priorities toward the other side of the world. Spain and its need for a single Coast Guard service that undertakes the responsibility for constabulary operations closer to home is a case in point for the necessary changes that allies will be forced to consider to succeed in this new age of great power competition at sea. The case for a Spanish Coast Guard is just an example among many others of the debates that European nations in NATO will have to face in order to make the most out of their limited resources, and find the most efficient ways to do so.

Gonzalo Vázquez is an associate researcher at the Spanish Naval War College’s Center for Naval Thought.

The author is thankful to LCDR Novoa for his comments and suggestions on earlier drafts.

The views voiced here are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily represent the official views of any government institution.

Featured Image: Don Inda-class offshore tugboat Clara Campoamor of the Spanish Maritime and Rescue Service (SASEMAR). (Photo by Santiago Mena)