This article originally featured at National Defense University’s Joint Force Quarterly and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Daniel Hughes and Andrew M. Colarik

Recent analysis of cyber warfare has been dominated by works focused on the challenges and opportunities it presents to the conventional military dominance of the United States. This was aptly demonstrated by the 2015 assessment from the Director of National Intelligence, who named cyber threats as the number one strategic issue facing the United States.1 Conversely, questions regarding cyber weapons acquisition by small states have received little attention. While individually weak, small states are numerous. They comprise over half the membership of the United Nations and remain important to geopolitical considerations.2 Moreover, these states are facing progressively difficult security investment choices as the balance among global security, regional dominance, and national interests is constantly being assessed. An increasingly relevant factor in these choices is the escalating costs of military platforms and perceptions that cyber warfare may provide a cheap and effective offensive capability to exert strategic influence over geopolitical rivals.

This article takes the position that in cyber warfare the balance of power between offense and defense has yet to be determined. Moreover, the indirect and immaterial nature of cyber weapons ensures that they do not alter the fundamental principles of warfare and cannot win military conflicts unaided. Rather, cyber weapons are likely to be most effective when used as a force multiplier and not just as an infrastructure disruption capability. The consideration of cyber dependence—that is, the extent to which a state’s economy, military, and government rely on cyberspace—is also highly relevant to this discussion. Depending on infrastructure resiliency, a strategic technological advantage may become a significant disadvantage in times of conflict. The capacity to amplify conventional military capabilities, exploit vulnerabilities in national infrastructure, and control the cyber conflict space is thus an important aspect for any war-making doctrine. Integrating these capabilities into defense strategies is the driving force in the research and development of cyber weapons.

The Nature of Cyber Warfare

Cyber warfare is increasingly being recognized as the fifth domain of warfare. Its growing importance is suggested by its prominence in national strategy, military doctrine, and significant investments in relevant capabilities. Despite this, a conclusive definition of cyber warfare has yet to emerge.3 For our purposes, such a definition is not required as the critical features of cyber warfare can be summarized in three points. First, cyber warfare involves actions that achieve political or military effect. Second, it involves the use of cyberspace to deliver direct or cascading kinetic effects that have comparable results to traditional military capabilities. Third, it creates results that either cause or are a crucial component of a serious threat to a nation’s security or that are conducted in response to such a threat.4 More specifically, cyber weapons are defined as weaponized cyber warfare capabilities held by those with the expertise and resources required to deliver and deploy them. Thus, it is the intent to possess the skills required to develop and deploy cyber weapons that must be the focus of any national security strategy involving cyber warfare.

Notable theorists have judged that in cyber warfare, offense is dominant.5 Attacks can be launched instantaneously, and there is rapid growth in the number of networks and assets requiring protection. After all, cyberspace is a target-rich environment based on network structures that privilege accessibility over security. Considerable technical and legal difficulties make accurate attribution of cyber attacks, as well as precise and proportionate retaliation, a fraught process.6 There is also the low cost of creating cyber weapons—code is cheap—and any weapon released onto the Internet can be modified to create the basis of new offensive capabilities.7 All of this means that the battlespace is open, accessible, nearly anonymous, and with an entry cost that appears affordable to any nation-state.

Strategies that rely too heavily on offensive dominance in cyber warfare may, however, be premature. Cyber dependence—the extent to which an attacker depends on cyberspace for critical infrastructure—is crucial to the strategic advantages that cyber weapons can provide. Uncertainty rules as the dual-use nature of cyber weapons allows them to be captured, manipulated, and turned against their creators.8 Equally important is the practice of “escalation dominance.”9 As shown by as yet untested U.S. policy, retaliation for a cyber attack may be delivered by more destructive military capabilities.10 And while the speed of a cyber attack may be near instantaneous, preparation for sophisticated cyber attacks is considerable. The Stuxnet attack required the resources of a technologically sophisticated state to provide the expansive espionage, industrial testing, and clandestine delivery that were so vital to its success. The above demonstrates that the true cost of advanced cyber weapons lies not in their creation but in their targeting and deployment, both of which reduce their ability to be redeployed to face future, unforeseen threats.

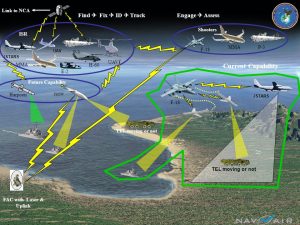

Cyber weapons are further limited by their lack of physicality. As pieces of computer code, they generate military effect only by exploiting vulnerabilities created by reliance on cyberspace.11 They can attack vulnerable platforms and infrastructures by manipulating computer systems or act as a force multiplier to traditional military assets. This may lead to the disruption and control of the battlespace, as well as to the provision of additional intelligence when payloads are deployed. These effects, however, are always secondary—cyber weapons cannot directly affect the battlefield without a device to act through, nor can they occupy and control territory.

Ultimately, the debate regarding the balance of power in cyber warfare and the relative power of cyber weapons will likely be decided by empirical evidence relating to two factors. The first is the amount of damage caused by the compromise of cyber-dependent platforms. The second will be the extent to which major disruptions to infrastructure erode political willpower and are exploitable by conventional military capabilities. For the moment, however, it is safe to presume that conflicts will not be won in cyberspace alone and that this applies as much to small states as it does to major powers.

Uses of Cyber Weapons by Small States

To be worthy of investment, a cyber weapons arsenal must provide states with political or military advantage over—or at the very least, parity with—their adversaries. To judge whether a small state benefits sufficiently to justify their acquisition, we must understand how these capabilities can be used. A nonexhaustive list of potential cyber weapon uses includes warfighting, coercion, deterrence, and defense diplomacy. As cyber weapons are limited to secondary effects, they currently have restricted uses in warfighting. Their most prominent effect likely will be the disruption and/or manipulation of military command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) capabilities and the degradation of civilian support networks. Attacks on civilian infrastructure remain most feasible, and attacks on automated military platforms are possible.12 The effective use of cyber weapons as a coercive tool is constrained by the relative size and cyber dependence of an opponent and carries the risk of weapons acting in unforeseen ways. Both of these dependencies are shared when cyber weapons are used as a deterrent. This is due to the peculiar nature of the cyber domain, where both coercion and deterrence rely on the same aggressive forward reconnaissance of an adversary’s network. This results in the difference between coercion and deterrence being reduced to intent—something difficult to prove. The final potential use of cyber weapons is as a component of defense diplomacy strategy, which focuses on joint interstate military exercises as a means to dispel hostility, build trust, and develop armed forces.13 This could be expanded to encompass cyber exercises conducted by military cyber specialists. Defense diplomacy can act as a deterrent, but it is effective only if relevant military capabilities are both credible and demonstrable.14 The latter is problematic. Advanced cyber weapons are highly classified; caution must therefore be exercised when demonstrating capabilities so that “live” network penetrations are not divulged.

These four capabilities have crucial dependencies, all of which can limit their suitability for deployment in a conflict. First, the conflicting parties must have comparable military power. Disrupting an opponent’s C4ISR will be of little consequence if they still enjoy considerable conventional military superiority despite the successful deployment of cyber weapons. Second, as demonstrated by the principle of cyber dependence, one state’s disruption of another’s cyber infrastructure is effective only if they can defend their own cyber assets or possess the capability to act without these assets with minimal degradation in operational effectiveness. Third, states must have the resources and expertise required to deploy cyber weapons, which increase commensurate with their efficacy. Fourth, cyber weapons rely on aggressive forward reconnaissance into networks of potential adversaries; weapons should be positioned before conflict begins. This creates political and military risk if an opponent discovers and traces a dormant cyber weapon. Finally, all use of cyber weapons is complicated by their inherent unpredictability, which casts doubts over weapon precision and effect. Once unleashed, the course of cyber weapons may be difficult to predict and/or contain.15 Unforeseen results may undermine relationships or spread to neutral states that then take retaliatory action.16 Accordingly, weapon deployment must follow sound strategy against clearly identified adversaries to minimize unforeseen consequences.

A Predictive Framework

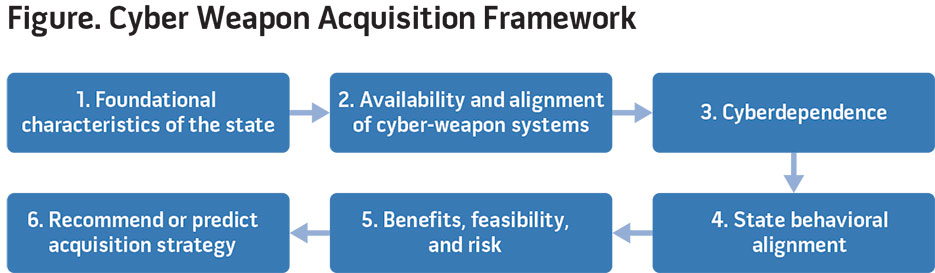

What is offered in this section is an analytical framework that may provide a customized evaluation of whether a particular small state should—or will—acquire cyber weapons. In essence, what is being provided is a baseline for a comparative, comprehensive study on a state-by-state basis. The framework itself yields its maximum value when numerous states have been analyzed. This enables potential proliferation patterns to emerge and a clearer picture of the threat landscape to present itself.

Each step is explained by a purpose statement and demonstrated through a case study. The subject of the case study is New Zealand, chosen due to its membership in the Five Eyes intelligence network and because it both self-identifies as and is widely perceived to be a small state.17 Ideally, each step of the framework would be completed by a group representing a variety of perspectives from military forces, government entities, and academic specialties. There is the potential for a much more detailed evaluation than that presented, which has been condensed for brevity.

Step One: Identify Foundational Small-State Characteristics. The purpose is to identify key characteristics of the small state within three categories: quantitative, behavioral, and identity.18 Quantitative refers to measures such as land area, population, and gross domestic product (GDP). Behavioral refers to qualitative metrics concerning the behavior of a state, both domestically and within the international system. Identity refers to qualitative metrics that focus on how a state perceives its own identity. This article proposes that metrics from each category can be freely used by suitably informed analysts to assign a size category to any particular state. This avoids the need for a final definition of a small state. Instead, definition and categorization are achieved through possession of a sufficient number of overlapping characteristics—some quantitative, some behavioral, and some identity based.19 Quantitatively, New Zealand has a small population (approximately 4.5 million), a small GDP (approximately $197 billion), and a small land area.20 It is geographically isolated, bordering no other countries. In the realm of behavior, New Zealand practices an institutionally focused multilateral foreign policy. It is a founding member of the United Nations and was elected to the Security Council for the 2015–2016 term after running on a platform of advocating for other small states. It participates in multiple alliances and takes a special interest in the security of the South Pacific.21 Regarding identity, New Zealand’s self-identity emphasizes the values of fairness, independence, nonaggression, cooperation, and acknowledgment of its status as a small state.22 Its security identity is driven by a lack of perceived threat that allows New Zealand to make security decisions based on principle rather than practicality.23 This was demonstrated by the banning of nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered ships within New Zealand waters, and its subsequent informal exclusion from aspects of the Australia, New Zealand, and United States Security Treaty. Despite reduced security, however, domestic opinion strongly supported the anti-nuclear policy that, along with support for nonproliferation and disarmament, has strengthened the pacifistic elements of New Zealand’s national identity.24

Step Two: Identify Resource Availability and Policy Alignment for Cyber Weapon Development, Deployment, and Exploitation. The purpose is to identify how the use of cyber weapons would align with current security and defense policies; whether the small state has the military capabilities to exploit vulnerabilities caused by cyber weapon deployment; and whether the small state has the intelligence and technical resources needed to target, develop, and deploy cyber weapons.

In key New Zealand defense documents, references to cyber primarily mention defense against cyber attacks, with only two references to the application of military force to cyberspace. There is no mention of cyber weapon acquisition. New Zealand’s defense policy has focused on military contributions to a secure New Zealand, a rules-based international order, and a sound global economy. Because the likelihood of direct threats against the country and its closest allies is low, there has been a focus on peacekeeping, disaster relief, affordability, and maritime patrol. New Zealand’s military is small (11,500 personnel, including reservists) with limited offensive capabilities and low funding (just 1.1 percent of GDP). Accordingly, the New Zealand military lacks the ability to exploit vulnerabilities caused by the successful use of cyber weapons.

New Zealand is a member of the Five Eyes intelligence network and thus can access more sophisticated intelligence than most small states. This can be used to increase its ability to target and deploy cyber weapons. It has a modern signals intelligence capability, housed by the civilian Government Communications Security Bureau, which also has responsibility for national cybersecurity. It most likely has the technical capability to adapt existing cyber weapons or develop new ones, particularly if aided by its allies. Due to fiscal constraints, however, any additional funding for cyber weapons will likely have to come from the existing defense budget and thus result in compromises to other capabilities.25

Step Three: Examine Small-State Cyber Dependence. The purpose is to examine the small state’s reliance on cyberspace for its military capabilities and critical infrastructure, as well as its relative cyber dependence when compared to potential geopolitical adversaries.

New Zealand has moderate to high cyber dependence, with increasing reliance on online services and platforms by the government, business sector, and civil society. This dependence will increase. For example, the acquisition of new C4ISR capabilities to increase military adoption of network-centric warfare principles would create new vulnerabilities.26New Zealand’s cyber dependence is further increased by limited cybersecurity expertise.27 It does not have obvious military opponents, so its relative level of cyber dependence is difficult to calculate.

Step Four: Analyze State Behavior Against Competing Security Models. The purpose is to analyze how state behavior aligns with each competing security model and how cyber weapon acquisition and use may support or detract from this behavior. Cyber weapon arsenals are used to advance political and military objectives. These objectives depend on a state’s behavior and identity, both of which are difficult to quantify. A degree of quantification is possible, however, through the use of conceptual security models. A synthesis of recent small- state security scholarship generates four models: the first focused on alliances, the second on international cooperation, and the third and fourth on identity, differentiated by competing focuses (collaboration and influence, and defensive autonomy).28 The alliance-focused model presents small states with persuasive reasons to acquire cyber weapons. This applies both to balancing behavior (that is, joining an alliance against a threatening state) and bandwagoning (that is, entering into an alliance with a threatening state).29 The additional military resources provided by an alliance present greater opportunities for the exploitation of vulnerabilities caused by cyber weapons. In the event that a cyber weapon unwittingly targets a powerful third party, a small state may be less likely to be subjected to blowback if it is shielded by a strong alliance. Furthermore, cyber weapons may be a reasonably cost-effective contribution to an alliance; a great power could even provide preferential procurement opportunities for a favored ally.

New Zealand maintains a close military alliance with Australia and is a member of the Five Power Defence Arrangements. It also has recently signed cybersecurity agreements with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and United Kingdom.30 The alliances above have focused on security and mutual defense rather than offensive capabilities. New Zealand does, however, have a policy of complementing Australian defense capabilities.31 This could be achieved through the acquisition of cyber weapons, so long as it was closely coordinated and integrated with the Australian military. Thus this model assesses state behavioral alignment as medium/high and cyber weapon support as medium/high.

The international cooperation model assumes that small states can exert influence by strengthening international organizations, encouraging cooperative approaches to security, and creating laws and norms to constrain powerful states.32 Small states acting under this model will favor diplomatic and ideological methods of influence. As such, they are less likely to acquire cyber weapons. Instead, it is more likely that they will try to regulate cyber weapons in a manner similar to the restrictions on biological and chemical weapons or by leading efforts to explicitly incorporate them into the international laws of warfare.

New Zealand usually pursues a multilateral foreign policy approach and is a member of multiple international organizations. It has a long history of championing disarmament and arms control, which conflicts with the acquisition of new categories of offensive weapons. This model assesses state behavioral alignment as high and cyber weapon support as low.

Both of the identity focused models (collaboration and influence versus defensive autonomy) are centered on analysis of a small state’s “security identity.” This develops from perceptions of “past behavior and images and myths linked to it which have been internalized over long periods of time by the political elite and population of the state.”33 This identity can be based around a number of disparate factors such as ongoing security threats, perceptions of national character, and historical consciousness. A state’s security identity can lead it toward a preference for either of the identity focused security models mentioned above.Regarding collaboration and influence, New Zealand’s identity strikes a balance between practicality and principle. It strives to be a moral, fair-minded state that advances what it regards as important values, such as human rights and the rule of law.34 It still wishes, however, to work in a constructive manner that allows it to contribute practical solutions to difficult problems. The acquisition of cyber weapons is unlikely to advance this model. Thus this model assesses state behavioral alignment as medium and cyber weapon support as low.

Despite its multilateral behavior, New Zealand retains some defensive autonomy and takes pride in maintaining independent views on major issues.35 Its isolation and lack of major threats have allowed it to retain a measure of autonomy in its defense policy and to maintain a small military. Its independent and pacifistic nature suggests that cyber weapon acquisition could be controversial. Thus this model assesses state behavioral alignment as medium and cyber weapon support as low/medium.

|

Table 1. Cyber Weapon Cost-Benefit Risk Matrix for New Zealand |

||||

|

Warfighting |

Coercion |

Deterrence |

Defense Diplomacy |

|

|

Benefits |

Ability to complement military capabilities of allies Cost effective offensive capability |

Limited coercive ability from cyber weapons |

Limited deterrence from cyber weapons |

Deterrence from demonstrating effective cyber weapons via defense diplomacy |

|

Feasibility |

Allies may provide favorable procurement opportunities Appropriate technical and intelligence resources exist |

Appropriate technical and intelligence resources exist |

Appropriate technical and intelligence resources exist |

Appropriate technical and intelligence resources exist |

|

Risks |

Procurement may result in reduced funding for other military capabilities Domestic opposition to acquisition of new offensive weapons Cyber weapon acquisition may reduce international reputation Cyber weapons exploitation relies on allied forces High level of cyber dependence increases vulnerability to retaliation |

Domestic opposition to acquisition of new offensive weapons Security identity not reconcilable with coercive military actions Procurement may result in reduced funding for other military capabilities Cyber weapon acquisition may reduce international reputation High level of cyber dependence increases vulnerability to retaliation |

Procurement may result in reduced funding for other military capabilities Cyber weapon acquisition may reduce international reputation High level of cyber dependence increases vulnerability to retaliation Lack of identified threats reduces ability to target and develop deterrent cyber weapons |

Procurement may result in reduced funding for other military capabilities Cyber weapon acquisition may reduce international reputation High level of cyber dependence reduces deterrent effect |

Step Five: Analyze Benefits, Feasibility, and Risk for Each Category of Cyber Weapon Use. The purpose is to first identify the benefits, feasibility, and risk of acquiring cyber weapons based on each category of potential use, as shown in table 1. Next this information is analyzed against the degree to which cyber weapon use may support different security models, as shown in table 2. This results in a ranking of the benefits, feasibility, and risk of each combination of cyber weapon use and small-state security model. This is followed by an overall recommendation or prediction for cyber weapon acquisition under each security model and category of cyber weapon use.

|

Table 2. Cyber Weapon Acquisition Matrix for New Zealand |

||||||

|

Security Model |

BFR |

Warfighting |

Coercion |

Deterrence |

Defense Diplomacy |

Overall |

|

Alliances |

Benefits |

Medium |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

|

Feasibility |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

|

|

Risk |

High |

Very High |

High |

Low |

High |

|

|

Recommendation/Prediction |

Further Investigation |

No |

No |

Further Investigation |

Further Investigation |

|

|

International cooperation |

Benefits |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

|

Feasibility |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

|

|

Risk |

High |

High |

High |

Low |

High |

|

|

Recommendation/Prediction |

No |

No |

No |

Further Investigation |

No |

|

|

Identity and norms: collaboration and influence |

Benefits |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Low |

|

Feasibility |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

|

|

Risk |

High |

High |

High |

Low |

High |

|

|

Recommendation/Prediction |

No |

No |

No |

Further Investigation |

No |

|

|

Identity and norms: defensive autonomy |

Benefits |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Feasibility |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

Medium |

|

|

Risk |

High |

High |

High |

Low |

High |

|

|

Recommendation/Prediction |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

Step Six: Recommend or Predict Cyber Weapon Acquisition Strategy. The purpose is to summarize key findings, to recommend whether a small state should acquire cyber weapons, and to predict the likelihood of such an acquisition. The key findings are that New Zealand is unlikely to gain significant benefits from the acquisition of cyber weapons. This is due to its limited military capabilities, multilateral foreign approach, extensive participation in international organizations, and pacifistic security identity. Factors that could change this evaluation and increase the benefits of cyber weapon acquisition would include an increased focus on military alliances, the emergence of more obvious threats to New Zealand or its close allies, or a changing security identity.

Therefore, the recommendation/prediction is that New Zealand should not acquire cyber weapons at this time and is unlikely to do so. The framework’s output has considerable utility as a decision support tool. When used by a small state as an input into a strategic decisionmaking process, its output can be incorporated into relevant defense capability and policy documents. If cyber weapon acquisition is recommended, its output could be further used to inform specific strategic, doctrinal, and planning documents. It also provides a basis for potential cyber weapon capabilities to be analyzed under a standard return-on-investment procurement model. This would involve a more detailed analysis of benefits, costs, and risks that would allow fit-for-purpose procurement decisions to be made in a fiscally and operationally prudent manner.

Alternatively, the framework, which is low cost and allows a variety of actors to determine the likelihood of cyber weapon acquisition by small states, could be used as a tool to develop predictive intelligence. Furthermore, when the framework is used on a sufficient number of small states, it could be used as a basis for making broader predictions regarding the proliferation of cyber weapons. This would be particularly effective over geographical areas with a large concentration of small states. For more powerful states, this might indicate opportunities for increased cyber warfare cooperation with geopolitical allies, perhaps even extending to arms sales or defense diplomacy. Conversely, the framework could provide nongovernmental organizations and academics with opportunities to trace cyber weapon proliferation and raise visibility of the phenomenon among international organizations, policymakers, and the general public. These outcomes provide significant benefits to the broad spectrum of actors seeking stability and influence within the international order.

Conclusion

The evolution of the various domains of warfare did not occur overnight. Learning from and leveraging the changing landscapes of war required continuous investigation, reflection, and formative activities to achieve parity, much less dominance, with rivals. Treating cyberspace as the fifth domain of warfare requires a greater understanding of the battlespace than currently exists. This goes well beyond the technological aspects and requires the integration of cyber capabilities and strategies into existing defense doctrines. The framework we have developed has the potential to help guide this process, from strategic decision to procurement and doctrinal and operational integration. Similarly, its predictive potential is significant—any ability to forecast cyber weapon acquisition on a state-by-state basis and thus monitor cyber weapon proliferation would be of substantial geopolitical benefit. We further propose that decisionmakers of large, powerful states must not ignore the strategic impact that small states could have in this domain. We also remind small states that their geopolitical rivals may deploy cyber weapons as a means to advance national interests in this sphere of influence. Therefore, it is our hope that, as a result of clarifying the potential conflict space, future policies might be developed to control the proliferation of cyber weapons. JFQ

Daniel Hughes is a Master’s Candidate with a professional background in Defense and Immigration. Andrew M. Colarik is a Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Defence and Security Studies, Massey University, New Zealand.

Notes

1 Senate Armed Services Committee, James R. Clapper, Statement for the Record, Worldwide Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, February 26, 2015, available at <www.dni.gov/files/documents/Unclassified_2015_ATA_SFR_-_SASC_FINAL.pdf>.

2 United Nations News Centre, “Ban Praises Small State Contribution to Global Peace and Development,” 2015, available at <www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=43172#.Vp87nip96Uk>.

3 Paulo Shakarian, Jana Shakarian, and Andrew Ruef, Introduction to Cyber Warfare: A Multidisciplinary Approach(Waltham, MA: Syngress, 2013); Catherine A. Theohary and John W. Rollins, Cyber Warfare and Cyberterrorism: In Brief, R43955 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, March 27, 2015), available at <www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R43955.pdf>.

4 Raymond C. Parks and David P. Duggan, “Principles of Cyber Warfare,” IEEE Security and Privacy Magazine 9, no. 5 (September/October 2011), 30; Andrew M. Colarik and Lech J. Janczewski, “Developing a Grand Strategy for Cyber War,” 7th International Conference on Information Assurance & Security, December 2011, 52; Shakarian, Shakarian, and Ruef.

5 Fred Schrier, On Cyber Warfare, Democratic Control of Armed Forces Working Paper No. 7 (Geneva: Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, 2015), available at <www.dcaf.ch/content/download/67316/…/OnCyber warfare-Schreier.pdf>; John Arquilla, “Twenty Years of Cyberwar,” Journal of Military Ethics 12, no. 1 (April 17, 2013), 80–87.

6 Stephen W. Korns and Joshua E. Kastenberg, “Georgia’s Cyber Left Hook,” Parameters 38, no. 4 (Winter 2008–2009).

7 P.W. Singer and Allan Friedman, Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

8 Parks and Duggan, 30.

9 Thomas G. Mahnken, “Cyberwar and Cyber Warfare,” in America’s Cyber Future, ed. Kristin M. Lord and Travis Sharp (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, 2011), available at <www.cnas.org/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/CNAS_Cyber_Volume%20II_2.pdf>.

10 Department of Defense (DOD), The DOD Cyber Strategy (Washington, DC: DOD, April 2015), available at <www.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/2015/0415_cyber-strategy/Final_2015_DoD_CYBER_STRATEGY_for_web.pdf>.

11 Joel Carr, “The Misunderstood Acronym: Why Cyber Weapons Aren’t WMD,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 69, no. 5 (2013), 32.

12 Sebastian Schutte, “Cooperation Beats Deterrence in Cyberwar,” Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy 18, no. 3 (November 2012), 1–11.

13 Defence Diplomacy, Ministry of Defence Policy Papers Paper No. 1 (London: Ministry of Defence, 1998), available at <http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121026065214/http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/BB03F0E7-1F85-4E7B-B7EB-4F0418152932/0/polpaper1_def_dip.pdf>.

14 Andrew T.H. Tan, “Punching Above Its Weight: Singapore’s Armed Forces and Its Contribution to Foreign Policy,” Defence Studies 11, no. 4 (2011), 672–697.

15 David C. Gompert and Martin Libicki, “Waging Cyber War the American Way,” Survival 57, no. 4 (2015), 7–28.

16 Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Cyber Power (Cambridge: Harvard Kennedy School, 2010), available at <http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/files/cyber-power.pdf>.

17 Jim McLay, “New Zealand and the United Nations: Small State, Big Challenge,” August 27, 2013, available at <http://nzunsc.govt.nz/docs/Jim-McLay-speech-Small-State-Big%20Challenge-Aug-13.pdf>.

18 Joe Burton, “Small States and Cyber Security: The Case of New Zealand,” Political Science 65, no. 2 (2013), 216–238; Jean-Marc Rickli, “European Small States’ Military Policies After the Cold War: From Territorial to Niche Strategies,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 21, no. 3 (2008), 307–325.

19 Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1958).

20 Statistics New Zealand, “Index of Key New Zealand Statistics,” available at <www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/index-key-statistics.aspx#>.

21 New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Foreign Relations,” March 2014, available at <http://mfat.govt.nz/Foreign-Relations/index.php>.

22 Ibid.

23 New Zealand Defence Force Doctrine, 3rd ed. (Wellington: Headquarters New Zealand Defence Force, June 2012), available at <www.nzdf.mil.nz/downloads/pdf/public-docs/2012/nzddp_d_3rd_ed.pdf>.

24 Andreas Reitzig, “In Defiance of Nuclear Deterrence: Anti-Nuclear New Zealand After Two Decades,” Medicine, Conflict, and Survival 22, no. 2 (2006), 132–144.

25 Defence White Paper 2010 (Wellington: Ministry of Defence, November 2010), available at <www.nzdf.mil.nz/downloads/pdf/public-docs/2010/defence_white_paper_2010.pdf>.

26 New Zealand Defence Force Doctrine.

27 Burton, 216–238.

28 Ibid.; Paul Sutton, “The Concept of Small States in the International Political Economy,” The Round Table 100, no. 413 (2011), 141–153.

29 Burton, 216–238.

30 Ibid.

31 Defence Capability Plan (Wellington: Ministry of Defence, June 2014), available at <www.nzdf.mil.nz/downloads/pdf/public-docs/2014/2014-defence-capability-plan.pdf>.

32 Ibid.

33 Rickli, 307–325.

34 McLay.

35 Ibid.

Featured Image: 13th annual Cyber Defense Exercise. (U.S. Army photo by Mike Strasser/USMA PAO)