By Steven Swingler

Introduction

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, there has been much interest and debate about what exactly is the political system in Russia. Officially, the country is a constitutional presidential federal state patterned off of the U.S. More cynical analysts and commentators will say that Russia is a dictatorship. In reality, the political system in Russia represents that of a Prussian constitutional system with the president serving the role of monarch and chancellor.

Supreme Powers

Russia’s president resembles a monarch in many ways. First, the president is not a member of the executive branch, but instead exists as more a protector of the Russian State and its people. The present Russian constitution evolved from the chaos of the 1990s in response to pressure from the west to adopt a more western style of government. The Russians agreed to these ideas to secure loans from the IMF, World Bank, and Western financial institutions as the economy was in shambles, and there was a huge need for capital to develop the nascent market economy. The new government was set up to resemble western democracies with a bicameral legislature, executive, and judicial branches. However, much greater powers were given to the executive branch. As article 80 of the Russian constitution states,

“The President of the Russian Federation shall be guarantor of the Constitution of the Russian Federation, of the rights and freedoms of man and citizen. According to the rules fixed by the Constitution of the Russian Federation, he shall adopt measures to protect the sovereignty of the Russian Federation, its independence and state integrity, ensure coordinated functioning and interaction of all the bodies of state power.”

The Russian constitution also states that the president is also given full control of the nation’s foreign policy (articles 80,86), has the ability to dissolve the legislature, the State Duma (article 84), is the sole commander of the Armed Forces (article 87), is given the ability to strike down laws that run contrary to his duties in article 80 (article 85), and finally has full immunity from prosecution for actions during his presidency (article 91). Also, the president may issue Ukases (roughly equivalent to executive orders in the U.S., but the name is taken from the decrees of the Tsar) which have the force of law, provided they are found to not contradict the Russian constitution. Such an order is unlikely to be deemed unconstitutional as the Russian Supreme Court has not directly challenged the Russian executive branch, and in 1993, President Boris Yeltsin simply ignored the directives of the court.

Why is there enormous power concentrated in the office of the president? Russian political culture and recent history are a major reason.

Historically Authoritarian

Throughout Russian history, despite the seeming strength of differing ideologies and governments, there has always been a strong autocrat or leader who rules through personal charisma, strength, and patronage. The tradition of centralized power with a strong leader has been a theme throughout Russian history. From the time of Ivan the Terrible (Gronzy) through the enlightenment, to the political fluctuations of the 19th and early 20th centuries, from Lenin to Stalin and then the later communist party secretaries, there has always been a central figure that has existed to represent the Russian state on the world stage and guarantee order through any means necessary.

This demonstrates a strong tradition of centralized personal rule in Russian history. This reveals an aspect of Russian politics that is foreign to westerners in that it is very individual-centered. Political parties are not so much defined by their ideology as by their leader. For example, Putin defines United Russia, Vladimir Zhirinovsky in the LDPR, Gennady Zyuganov with the modern communist party, or even in the old Bolshevik party, Lenin and later Stalin all affected policy just as deeply as the official ideology. This person-centric foundation of Russian politics further reinforces the tendencies of personal authoritarian rule , because instead of serving an institution or an ideology, bureaucrats and politicians are tied to serving an individual.

These historical trends, combined with the circumstance of the late Soviet Union and the personality of Boris Yeltsin, shaped and defined the powerful modern Russian presidency.

The Death Throes of a Superpower

In the latter years of the Soviet Union, the USSR was plagued by the ineffective leadership of an ailing Leonid Breznhev, followed by his geriatric contemporaries, and finally the idealistic, but unrealistic and ineffectual Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev’s haphazard reforms and continued adherence to communist ideology did little to stem the economic hemorrhaging of the Soviet Union or improve the lives of ordinary Soviet citizens.

As a result, people began to abandon the USSR and communist party and embrace nationalism and capitalism. Boris Yeltsin was the foremost of these nationalistic and capitalistic leaders in the Russian Soviet Federative Republic (RSFR). In response to a coup by Communist hardliners in the KGB and army against Gorbachev in 1991, Boris Yeltsin gave a speech from a tank and ordered the armed forces to disperse. This action destroyed the political legitimacy of Gorbachev and cemented Yeltsin’s control of Russia. Yeltsin then went on to dissolve the Soviet Union and remove Gorbachev from power.

In 1993, after two-and-a-half years of economic stagnation, the Supreme Soviet of Russia (the country’s legislature) and the nationalistic supporters of Alexander Rutskoy refused to ratify Yeltsin’s reforms. Yeltsin then attempted to dissolve the Supreme Soviet. The Supreme Soviet declared this action unconstitutional, voted to impeach Yeltsin, and proclaimed Alexander Rutskoy president with pro-Soviet paramilitaries barricading the legislature building. Yeltsin then used the majority vote he received on a non-binding referendum about confidence in his government as justification to declare the Supreme Soviet and Rutskoy “Fascist-Communist Revanchists” and had tanks and special forces shell and storm the Supreme Soviet. Yeltsin’s moves lead to the subordination of the Legislature to the office of the president and resulted in the president being granted the power to disband the new Russian legislature, the State Duma, and to be sole commander of the Armed and Security Forces.

Putin’s Bold Moves

As the 1990s went on, Russia’s economic situation continually worsened, and there was a major war in Chechnya and a widespread terrorist threat in Russia itself. Boris Yeltsin had several heart attacks, and by the late 1990s his advisors and oligarchs essentially ran the country. On the last day of 1999, Putin was appointed President of the Russian Federation when Yeltsin resigned. He was then elected in an election in March of 2000. At that time, the Russian economy was in dire straits due to disastrous privatization, the 1998 financial crisis, and the subsequent collapse of the Ruble. Regional governors were increasingly ignoring the central government, oligarchs and Yeltsin’s close friends increasingly ran the country through an ailing figurehead president, the government was facing massive deficits, and Chechen rebels and radical islamists were running amok in the Caucasus and launching an escalating terrorist campaign. In short, Russia was in a time of crisis.

In his first term, Putin rapidly moved to stop the bleeding. When Chechen rebels and Islamists invaded the neighboring Russian subject of Dagestan, Putin reacted decisively. The offensive was beaten back and 80,000 Russian troops invaded Chechnya proper. They laid siege to the capital city of Grozny, flattening the city block by block with airpower and heavy artillery, then rooting out survivors with infantry and armor supported by massive fire support. Across Chechnya fighting was fierce and the Russians and Pro-Moscow Chechen Militia’s took no prisoners, and launched a campaign of state terror and suppression reminiscent of Stalinist times.

In the course of the two Chechen wars and resulting and ongoing insurgency, it is estimated that 200,000 Chechen civilians, 25,000 Russian troops, and roughly 30-40,000 Chechen fighters perished. But surprisingly, despite the large-scale slaughter and massive human rights violation, the Russian public was remarkably silent. In an independent survey of the Russian population during the middle of the Chechen war, the only objection that two-thirds of the population had was complaints about the number of Russian servicemen killed in relation to Chechens. Misgivings about human rights, the fate of the Chechens, or the growth of executive power barely cracked 15 percent. Generally speaking, this reveals major cultural and values differences between the majority of Russians and Americans and Western Europeans. Russians care less for human rights and constitutional protections but instead are more concerned with personal safety, economic well-being, and stability and order for the country. These values combined with the consensus amongst Russian elites that Russia must be an independent great power has lead Russia to resist the so-called “Washington consensus” and try to cobble together its own conception of political philosophy, global roles, and (unsuccessfully) ideology.

Consolidation

Flush with popular support from the successful conflict in Chechnya, the crushing of the oligarchs and cowing of most major political opposition, Putin then used all levers of power inherited from the Yeltsin years to implement a series of reforms.

Putin overhauled and consolidated the entire Russian legal and tax codes while reorganizing local and regional governments. To counteract the growing regional separatism of the Yeltsin Era, the subnational governments were consolidated into seven large federal districts directly overseen by Moscow. Additionally, almost every kind of administrative code and regulation was overhauled, including labor, public administration, criminal law, commercial, and civil law. Finally, in an effort to reduce the complexity and widespread tax evasion of income taxes in Russia, a flat tax rate of 13 percent was instituted.

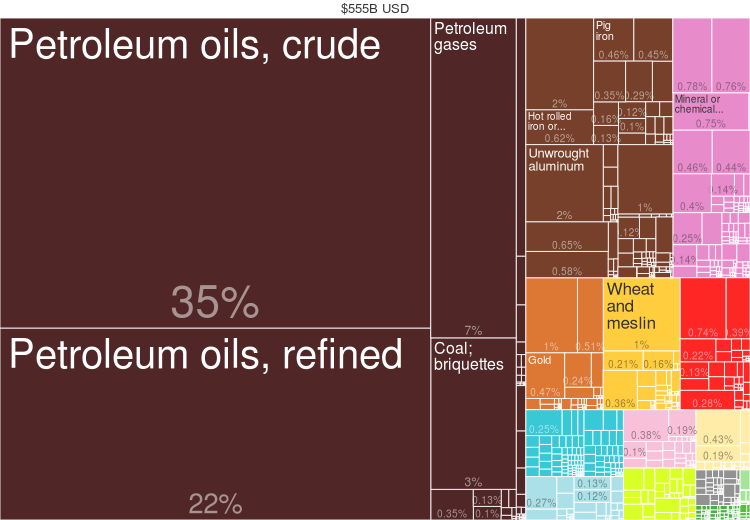

While the reforms made great progress in increasing the growth of the Russian economy and generating political success for Vladimir Putin and the ruling United Russia Party, a large part was due to extremely high oil and gas prices and the massive revenues state-owned energy companies generate. In fact, a third of Russia’s GDP comes from the state-owned energy sector. The largest and most profitable corporations are mostly state-owned such as the extremely lucrative arms industry which accounts for 20 percent of Russia’s manufacturing jobs. The Russian government has also so far avoided constructing a large scale and efficient tax system and has been able to redistribute wealth to legitimatize the existing political order, both in social programs for the people, and allowing some government funds to “disappear” to buy off elites.

As a result, not only is the Russian government not collecting a large amount of taxes from its citizens, but the majority of the economy and a large number of Russian workers are either directly or indirectly employed by the state. This gives Putin and United Russia a large constituency who are dependent on the regime for their economic livelihood and crowds out space in the Russian economy for strong and independent corporations or the rise of a middle class that could lead a viable liberal opposition.

In stabilizing the economic and political situation of the country, Putin continued his brand of brutal and direct but effective pragmatism. In the immediate aftermath of Yeltsin’s resignation, a significant portion of Yeltsin loyalists and oligarchs grew rich plundering state property. Putin moved against the oligarchs, refusing to appoint them to state positions, trying them for tax evasion, and trumped up charges which culminatedwith the Yukos affair. Yukos was an energy corporation lead by politician and oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky that managed to control most of the former Soviet Union’s oil and gas production. The Russian government charged Yukos with massive tax evasion and antitrust violations and was subsequently broken up and absorbed into the Russian State Energy Company (GAZPROM, Газпром) and Rosneft.

Despite the disregard of private property and massive executive influence on the judiciary, Russian public opinion polls favored the move. In a poll taken at the time, 54 percent of the population viewed the arrest as positive, 29 percent were indifferent, and only 13 percent of the populace viewed it negatively

Much of these state owned corporations were re-nationalized and lucrative positions were given to loyal Putin supporters. The oligarchs that were allowed to keep their holdings had to demonstrate loyalty to the ruling party or else face confiscation and exile. In addition, because of the lack of a clearly defined and motivating ideology of the United Russia party, the government oftentimes engages in corruption to buy support and co-opt more opportunistic and less ideological political actors.

Another deliberate act of Putin has been co-opting the the Force block in Russian Politics or Silovik ( силовики). The Siloviks consisted of former and current members of the Armed Forces, Intelligence Service, Internal Security, and Law Enforcement. These men are seen to be apolitical and more focused on the national interest than ordinary politicians. In the aftermath of the ineffective Yeltsin government, large numbers of them were voted into office or appointed. These officials usually have a weaker commitment to democracy and are either personally loyal to Putin and serve as a non-democratic source of power and buttress for the regime. Oftentimes men such as these were given good positions in state-owned corporations or were informally allowed to engage in corrupt practices to further cement their loyalty to the regime.

Challenges to Stability

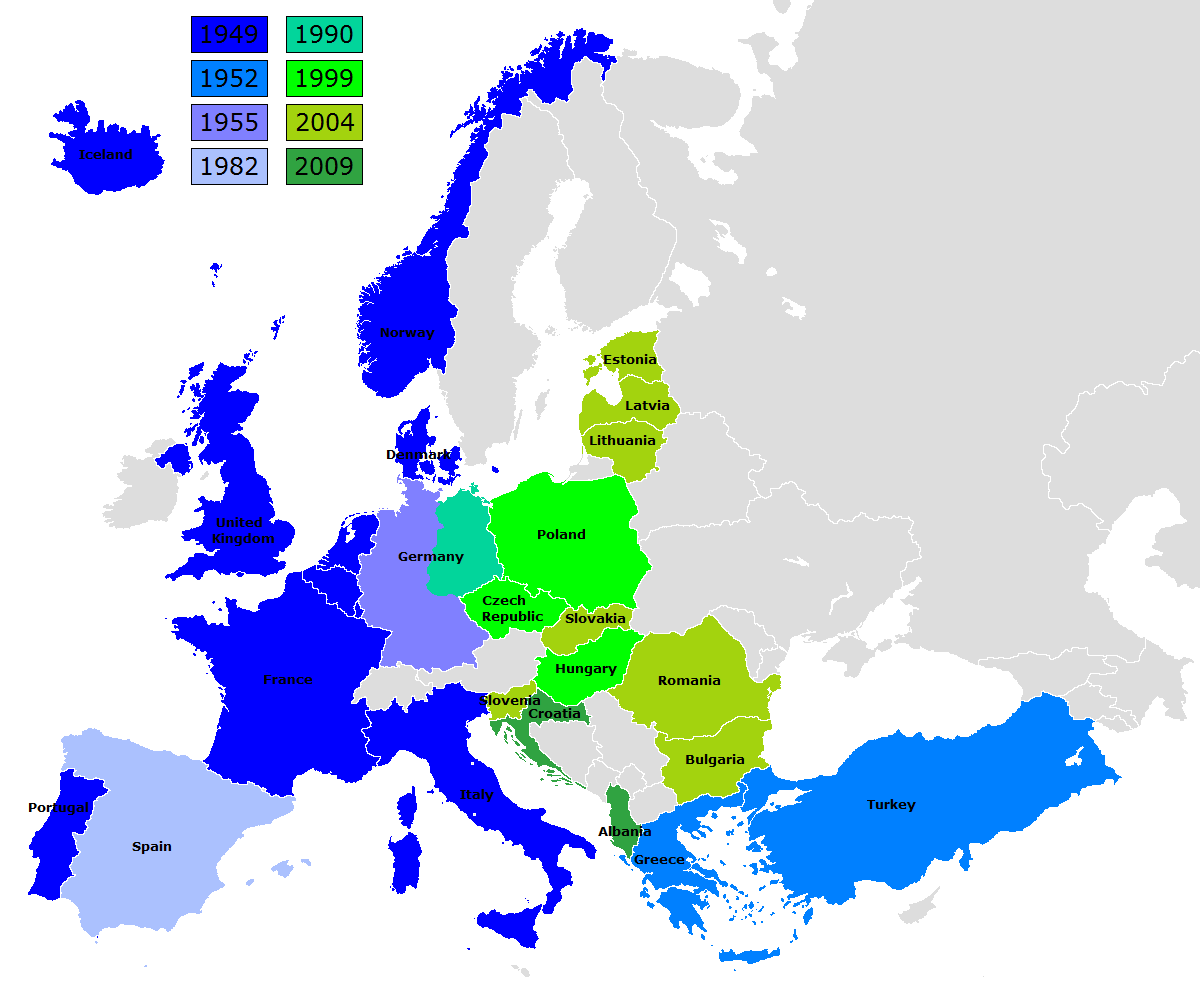

While Putin’s regime looks stable, there are several growing problems that could pose major problems to United Russia’s rule. Chief among them is the discovery and wide-scale exploitation of unconventional energy sources such as shale oil and intensified natural gas production that has created a large downward pressure on energy prices. In addition, these new sources of energy will allow Russia’s traditional European customers to move away from dependence upon Russian oil and avoid the possibility of “Energy Blackmail.” Given massive government revenues and GDP growth driven by the energy sector, this could undermine the economic and fiscal underpinnings of the Putin regime.

Second, while United Russia was able to win the recent Duma elections, there was widespread fraud and as a result, has triggered protests and greater unpopularity of the ruling United Russia party. While this is not a direct threat to the Putin regime, more coercion will have to be used to stay in power, which will harm Russia’s international standing and foreign investment, and by extension, the economic pillars of Putin’s rule.

The biggest future problem is what will happen after Vladimir Putin retires. United Russia could break apart after Putin’s death in Russia’ individual-centric political culture. Putin has also worked to create a cult of personality and his popularity with the masses is independent of United Russia’s. There is simply no one else inside United Russia that has both the popularity, legitimacy, and support of the military, security, and government institutions to take control of power after Putin.

Conclusion

The office of the president of the Russian Federation serves in a role similar to and has powers approaching that of the more Liberal reformist Czars of the late Imperial Period. Theirs is a historical tradition of a single person, centralized, personality-driven, and authoritarian rule that stretches back to the inception of the Russian state. While the president is not a supreme autocrat, Russian political history and Boris Yeltsin’s drive to consolidate power in the 1990s has created an extremely powerful presidency. Vladimir Putin used these powers to great effect in the early 2000s to stabilize the critical situation of Russia which further amplified the powers of the president. While the president does allow some form of elections and allows a parliament to exist (ironically named after the ineffectual Czarist-era Duma), the president controls the coercive levers of power and the lion’s share of the economy of the nation. In these ways, the modern Russian presidency and regime of Vladimir Putin exerts a level of control that is de facto close to the level of late 19th century Tsars.

Steven Swingler is a senior at Indiana University Bloomington and is pursuing his undergraduate degree in Political Science. Steven has studied abroad at the Moscow School of Higher Economics and at King’s College in London. He has interned at the Washington Office of U.S. Senator Dan Coats and the Congressional Joint Economic Committee.

Featured Image: Russian President-elect Vladimir Putin during the Russian presidential inauguration ceremony in 2012. (Reuters/Alexsey Druginyn)