This article was submitted in response to the call for articles on the law of naval warfare jointly issued by CIMSEC and the Stockton Center for International Law at the Naval War College.

By Dennis E. Harbin, III

The “Fellowship of the Sea” and the Law of Naval Warfare

“…may humanity after victory be the predominant feature in the British Fleet.”—Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson’s prayer prior to the Battle of Trafalgar, 1805

One of the main purposes of the law of war is “protecting combatants, noncombatants, and civilians from unnecessary suffering.”1

Given the uniqueness of the operating environment, this purpose takes on a special meaning for the conduct of operations at sea and informs the body of international law known as the law of naval warfare. These laws codify and bind belligerents to restrain their use of violence with principles of military necessity, honor, humanity, distinction, and proportionality.2

In particular, that the principle of humanity animates the law of naval warfare has a lot to do with what Professor L.F.E. Goldie described as the “fellowship of the sea.”3 If humanity as a law of war principle “forbids the infliction of suffering, injury, or destruction unnecessary to accomplish a legitimate military purpose,”4 then the law of naval warfare — whether in the age of sail or the cyber age — must conform to this special fellowship.

How conflict in the future maritime security environment, with technological advancements such as artificial intelligence and unmanned robotics, will stress historical interpretations of the law of naval warfare is worth discussing. However, this concern isn’t new. As Professor Goldie reflected 31 years ago, “[s]hould a contest for mastery of the oceans come about under contemporary conditions, it would be awesome in its magnitude…[and] may also challenge their humanity.”5

In 2018, then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford declared that “[w]hile the fundamental nature of war has not changed, the pace of change and modern technology, coupled with shifts in the nature of geopolitical competition, have altered the character of war in the 21st century.”6

While the character of war may have changed, its violent nature and challenge to virtues of humanity has not. Therefore, despite new technologies that allow access to new domains, academics and practitioners should also reexamine historical situations as well. The intent of this article is to renew focus on the law of naval warfare related to submarines and their ability to preserve the “fellowship of the sea.”

Specifically, whether modern armed conflict at sea has modified the submarine’s obligation to rescue survivors of targeted merchant vessels is worthy of consideration. This legal issue is unique in the law of naval warfare because it has been examined under the scrutinous light of litigation, yet remains “one of the least developed areas of the law of armed conflict.”7 To aid in understanding this 20th century legal issue in light of the 21st century maritime security environment, this article will call upon a historic milestone — the 75th anniversary of the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg.

Naval Warfare on Trial at Nuremberg

“Over the last six decades, the word ‘Nuremberg’ has become synonymous with humankind’s highest ideals and aspirations — a measuring stick against which all subsequent humanitarian ventures have been measured.”8 This year marks the 75th anniversary of the International Military Tribunal (IMT), when 21 senior German political and military leaders were put on trial by the Allied Powers for violations of international law.9

“There is no doubt that, with the benefit of over six decades of hindsight, we can say that the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg (IMT) was an event of world-historical importance. It was the first successful international criminal court, and has since played a pivotal role in the development of international criminal law and international institutions.”10 From November 1945 to October 1946, testimony was heard and documents produced that ultimately resulted in judges from the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union finding 19 defendants guilty of some or all of the charges of crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Herman Goering would commit suicide the night before he was to be executed. Ten would hang.

At first glance, the Nuremberg experience may have little to do with naval warfare, especially submarine warfare in the future maritime security environment. After all, most view the atrocities committed by the Nazis through the lens of the devastation of an aggressive war on the European continent and the horrors of the Holocaust. The trial of Grand Admirals Raeder and Doenitz, however, are particularly informative to understanding the law of naval warfare – especially submarine warfare in the case of Grand Admiral Doenitz.

Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz began the war as the commander of the Kriegsmarine’s submarine fleet and would end the war as Hitler’s successor as Germany’s head of state for Germany. After the dissolution of the German government on May 23, 1945, Doenitz was arrested, imprisoned, and later charged on all three counts under the Nuremberg Charter — crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.11 Despite succeeding Hitler at the end of the war, Doenitz would be sentenced to only ten years in prison. He was found guilty of, inter alia, breaches of the international law of submarine warfare.

Relevant to this article, the IMT found that Doenitz violated the 1936 London Naval Protocol for ordering his submarine commanders not to rescue the crews of targeted merchant vessels.12 British prosecutor Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe intended to prove that Doenitz violated international law when, in early 1940, Doenitz prohibited his U-Boat commanders from rescuing after their attacks any civilian survivors in the water. Known as Standing Order 154, Doenitz was convicted for issuing the following:

“Do not pick up survivors and take them with you. Do not worry about the merchant ship’s boars. Weather conditions and the distance to land play no part. Have a care only for your own ship and think only to attain your next success as soon as possible. WE must be harsh in this war. The enemy began the war in order to destroy us, so nothing else matters.”13

For readers that may think decisions made by the Nazi Admiralty three-quarters of a century ago has little bearing on the operations of the United States or its Allies, consider one of the reasons why Doenitz — again, Hitler’s successor — was given such a relatively light sentence.

Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, the U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander during World War II, is well known for his leadership and strategic contributions in the Pacific theater. His contribution in the European theater — and specifically his impact on the punishments adjudicated in Nuremberg — is much less known and is one of the more fascinating stories of the consequential IMT.

How Nimitz came to be involved in the IMT was in no small part due to the litigation skills of Doenitz’s defense counsel, Otto Kranzbuehler. Looking closely at the photos taken during the trial, one may notice a German naval officer, in uniform, but not sitting in the defendant’s box. Otto Kranzbuehler served as the Kriegsmarine’s Fleet Judge Advocate (Flottenreichter) at Germany’s surrender. In an interview for the 50th anniversary of the IMT, he told the story of his discovery of a small book about the pacific war in an American library, and how it inspired him to involve Nimitz.14

After intense litigation, it was the American judge, Francis Biddle, who ultimately insisted that the interrogatories go to Nimitz and that his answers be entered into the record in defense of Doenitz. Through his forceful arguments and creative thinking, Flottenreichter Kranzbuehler was able to produce proof for the IMT that the 1936 London Naval Protocol was, in practice, operationally deficient.

Specifically, when Kranzbuehler asked via interrogatory whether U.S. submarines were “prohibited from carrying out rescue measures toward passengers and crews of ships sunk without warning…,”15 Nimitz responded that “on general principles the U.S. submarines did not rescue enemy survivors if undue additional hazard to the submarine resulted or [if] the submarine would thereby be prevented from accomplishing its further mission.”16 Nimitz’s sworn response not only proved that the Allies were acting similarly to the Germans on this matter, but more importantly proved the impracticality of the law itself.

Despite what Doenitz declared as the “code of hardiness,” “which forswore every principle of the sea’s fellowship – mutual help in the face of nature, instant assistance to the shipwrecked, magnanimity in victory and fair play at all times,”17 the IMT did not include the waging of unrestricted submarine warfare when calculating his sentence due, in part, to Nimitz’s answers to Kranzbuehler’s interrogatories.18 When examined under the bright light of adversarial litigation, violating the 1936 London Naval Protocol which sought to enforce the “fellowship of the sea,” became an unpunishable offense.

State of the Law of Submarine Warfare

Before discussing how submarines will likely play a critical role in the future maritime security environment, it is helpful to examine the current state of the law by examining three relevant sources related to the law of naval warfare and submarine operations.

1. 1936 London Naval Protocol

A history of the 1936 London Naval Protocol is outside the scope of this article.19 The critical takeaways are threefold. First, the IMT used the Protocol to determine Grand Admiral Doenitz’s criminality. Second, submarines in their operations against merchant ships are obligated to adhere to the same visit and search, as well as rescue, rules for surface vessels. Specifically, the Protocol states:

“In particular, except in the case of persistent refusal to stop on being duly summoned, or of active resistance to visit or search, a warship, whether surface vessel or submarine, may not sink or render incapable of navigation a merchant vessel without having first placed passengers, crew and ship’s papers in a place of safety. For this purpose the ship’s boats are not regarded as a place of safety unless the safety of the passengers and crew is assured, in the existing sea and weather conditions, by the proximity of land, or the presence of another vessel which is in a position to take them on board.”20

The final takeaway, particularly relevant to this article and for the application of the law of naval warfare in the future maritime security environment, is that while the United States remains legally bound to the terms of the 1936 London Naval Protocol, China does not. It neither signed the 1930 London Treaty nor the 1936 London Naval Protocol.

2. The San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea

Prepared by a group of “legal and naval experts…the purpose of the [San Remo] Manual is to provide a contemporary restatement of international law applicable to armed conflicts at sea.”21 Although non-binding, the San Remo Manual reiterates the foundational position that submarines are obligated by the same rules as surface ships.22 In practice, a submarine may only target an enemy merchant vessel if:

(a) the safety of passengers and crew is provided for; for this purpose, the ship’s boats are not regarded as a place of safety unless the safety of the passengers and crew is assured in the prevailing sea and weather conditions by the proximity of land or the presence of another vessel which is in a position to take them on board;

(b) documents and papers relating to the prize are safeguarded; and

(c) if feasible, personal effects of the passengers and crew are saved.23

3. The U.S. Navy Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations

The U.S. Navy’s interpretation of the law of naval warfare related to submarine operations against merchants are consistent with the 1936 London Naval Protocol and the San Remo Manual. As a baseline, the Handbook still requires submarines to “search for and collect the shipwrecked, wounded, and sick following an engagement.”24

Although at first glance this may seem extreme relative to the realities of modern submarine warfare, the caveat to the rule is expansive. The Handbook continues, stating “If such humanitarian efforts would subject the submarine to undue additional hazard or prevent it from accomplishing its military mission, the location of possible survivors should be passed at the first opportunity to a surface ship, aircraft, or shore facility capable of rendering assistance.”25 Given that the purpose of the Handbook is to be of more practical usage to non-lawyer naval commanders, its discussion on these basic rules discussed above are particularly informative. Attempting to define circumstances that would “subject the submarine to undue additional hazard,” the Handbook lists the following examples:

-

- The enemy merchant vessel persistently refuses to stop when duly summoned to do so. 2. It actively resists visit and search or capture.

- It is sailing under convoy of enemy warships or enemy military aircraft.

- It is armed with systems or weapons beyond that required for self-defense against terrorism, piracy, or like threats.

- It is incorporated into, or is assisting in any way the enemy’s military intelligence system.

- It is acting in any capacity as a naval or military auxiliary to an enemy’s armed forces. 7. The enemy has integrated its merchant shipping into war-fighting/ war-supporting/ war-sustaining effort, and compliance with the London Protocol of 1936 would, under the circumstances of the specific encounter, subject the submarine to imminent danger or would otherwise preclude mission accomplishment.26

Submarines and Merchant Vessels in the Future Maritime Environment

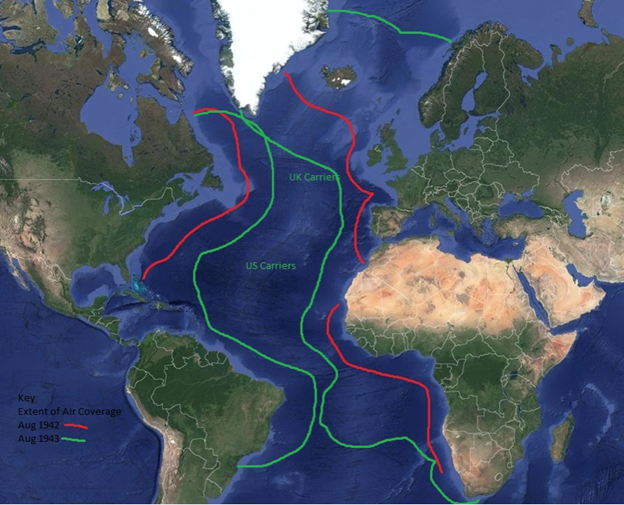

Upon examining the law of naval warfare related to submarines, an author in the U.S. Naval War College’s International Law Studies concluded more than 20 years ago that “it is highly probable that in any World War III belligerents will again find reasons why the 1936 London Submarine Protocol should not be applied…[and] in any future armed conflict of lesser extent than a World War III, the pressure of neutral Powers may be sufficiently strong to cause the belligerents to comply with the provisions of the 1936 London Submarine Protocol.”27

The reliance on submarines in future naval warfare is a cornerstone of the U.S. Navy’s plan to implement integrated, all-domain naval power. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Michael Gilday has recognized that “the advantage we have in the undersea [environment] is an advantage that we need to not only maintain, but we need to expand.”28 His 2021 Navigation Plan acknowledges that, in order to “deliver the all-domain naval power America needs to win…the Navy requires a greater number of submarines….”29 Moreover, the Navy’s Battle Force 2045 reflects the importance of submarines in the changing character of war as well.

Then-Secretary of Defense Mark Esper remarked that “there was clear consensus over months of study and war-gaming and analysis that we need to build more submarines, more attack submarines. And if we do nothing else we should invest in attack submarines, because of the lethality that they can deliver under the sea and the survivability that they have in clear overmatch that we have when it comes to the under sea domain and submarines in particular.”30 This focus has transferred across Presidential administrations as well. As reported recently, “as the [Biden] White House positions itself to argue on behalf of its budget proposal, new attack submarines apparently are a top priority.”31

The United States is not the only great power investing in its submarine force.32 The Chinese are also investing heavily in their future submarine fleet as well.33 As reported in October 2020, satellite images showing expansive building at a Chinese naval shipyard confirms the Office of Naval Intelligence’s forecast that “China’s submarine fleet [will] grow by six nuclear-powered attack submarines by 2030.”34

In addition to the likely critical role submarines will play in the next maritime war, its impact on commerce and trade will be tremendous. As an American naval officer testified during the IMT 75 years ago, “commerce and trade are now so identified with military power in total warfare that merchant ships, armed or unarmed, are in effect warships to be attacked and sunk without warning.”35

One-third of global commerce transits the South China Sea, arguably the world’s most contested maritime security hot spot.36 “As the second-largest economy in the world with over 60 percent of its trade in value traveling by sea, China’s economic security is closely tied to the South China Sea.”37 Given China’s and the U.S.’s reliance on commercial shipping in that area, it is not difficult to imagine that merchant vessels will once again be the targets of submarines in future maritime warfare.

Conclusion

It is difficult, however, to imagine a nuclear submarine surfacing to take on survivors. The impracticability of this practice was evident during the IMT proceedings when Flottenreichter Kranzbuehler produced Nimitz’s sworn responses and the Allies failed to punish Doenitz for violating the 1936 London Naval Protocol, which in effect ended the “fellowship of the sea.”

It is also not difficult to imagine that the “fellowship of the sea,” at least when it relates to submarine warfare, will continue to erode in the future maritime security environment. In fact, Nimitz is believed to have declared during the IMT that the “United States would probably wage unrestricted submarine warfare in future naval wars, based on its success in the Pacific War.”38

Maintaining rules that are impractical and operationally unrealistic undermines the rule-of-law. The IMT experience 75 years ago suggests that, when examining the law of naval warfare in the future maritime security environment, policy-makers must consider how keeping old rules may do more harm than good. As maritime security tensions again arise in the Pacific, where emerging technologies give commanders greater capability while requiring them to think faster, we need realistic rules and expectations that reflect operational realities. However, because the principle of humanity is a cornerstone of the law of naval warfare, policy-makers and commanders must strike a balance and strive to make and interpret rules that continue to uphold the centuries-old “fellowship of the sea.”

Lieutenant Commander Dennis Harbin is a Navy judge advocate currently serving on the Joint Staff. The views presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

Notes

[1] U.S. Dep’t of Def., DoD Law of War Manual para. 1.3.4, (May 2016).

[2] Ibid. at para. 1.4.2.

[3] L.F.E. Goldie, Targeting Enemy Merchant Shipping: An Overview of Law and Practice, 65 Int’l L. Studies 3 (1993).

[4] U.S. DEP’T OF DEF., DOD LAW OF WAR MANUAL para. 2.3 (May 2016).

[5] Goldie, supra note 3.

[6] Joseph Dunford, The Character of War and Strategic Landscape Have Changed, 89 Joint Forces Quarterly 2 (2nd Quarter, 2018).

[7] U.S. Dep’t of Navy., Navy Warfare Pub. 1-14M, The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations para 8.7.1 (2017) [hereinafter Handbook].

[8] Aaron Fichtelberg, Fair Trials and International Courts: A Critical Evaluation of the Nuremberg Legacy, 28 Criminal Justice Ethics no. 1 (2009).

[9] On November 19, 2020, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School hosted a symposium on the 75th anniversary of the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. For articles and presentation recordings regarding the history and legacy of the IMT, See The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg: Examining Its Legacy 75 Years Later.

[10] Fichtelberg, supra note 7.

[11] Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal 310 (1947) [hereinafter Judgement].

[12] Ibid. at 313.

[13] The Trial of Admiral Doenitz, 1 The ONI Review no. 12, October 1946, at 33.

[14] For recording of interview, see https://www.roberthjackson.org/nuremberg-event/nimitz-doenitz/.

[15] 17 Nuremberg Trial Proceedings (July 2, 1946),

[16] Ibid.

[17] Goldie, supra note 3.

[18] Judgement, supra note 10 at 313.

[19] See Howard Levie, Submarine Warfare: With Emphasis on the 1936 London Protocol, 65 Int’l L. Studies 325-26 (1993). Provides an expert and through history on the development of the 1936 London Naval Protocol.

[20] See Procès-verbal relating to the Rules of Submarine Warfare set forth in Part IV of the Treaty of London of 22 April 1930. London, 6 November 1936.

[21] See Int’l Institute of Humanitarian Law, San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea (Lousie Doswald-Beck ed., 1995) [hereinafter San Remo Manual],

[22] San Remo Manual, supra note 20, art. 45.

[23] San Remo Manual, supra note 20, art. 139.

[24] Handbook, supra note 6, para 8.7.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Handbook, supra note 6.

[27] Howard Levie, Submarine Warfare: With Emphasis on the 1936 London Protocol, 65 Int’l L. Studies 325-26 (1993).

[28] Sam LaGrone, CNO Gilday Lays Out Priorities for ‘DDG Next’ Warship, New Attack Submarine, USNI News (Oct. 14, 2020).

[29] U.S. Dep’t of Navy, CNO NAVPLAN (January 2021).

[30] Mark Esper, Secretary of Defense Remarks at CSBA on the NDS and Future Defense Modernization Priorities (Oct. 6, 2020).

[31] David Axe, Joe Biden Wants To Spend Big On U.S. Navy Submarines, Forbes (Apr. 12, 2021).

[32] Daniel Vegel, A Silent Destabilizer in the Indo-Pacific, Proceedings (March 2021).

[33] H. I. Sutton, Chinese Increasing Nuclear Submarine Shipyard Capacity, USNI News (Oct. 12, 2020).

[34] Ibid.

[35] Joel Holwitt, Execute Against Japan 178 (2009).

[36] How Much Trade Transits the South China Sea?, CSIS China Power Project (last viewed May 13, 2021).

[37] Ibid.

[38] Holwitt, supra note 34.

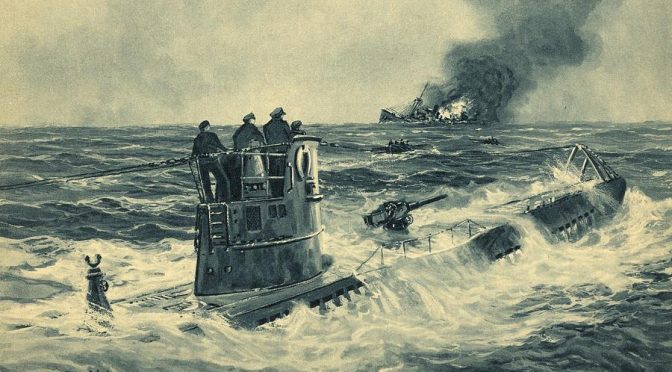

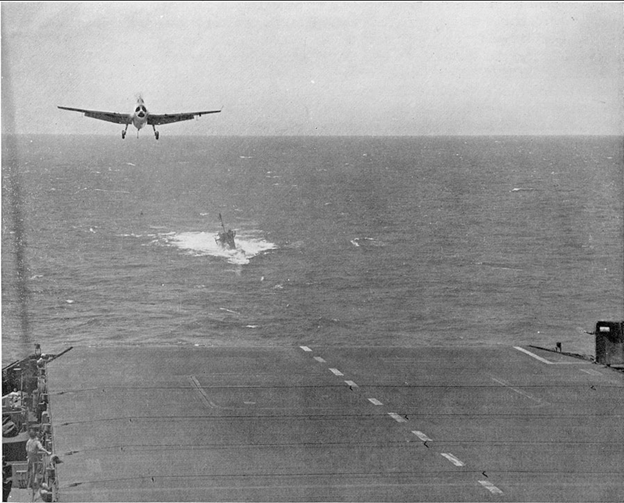

Featured image: Artwork of German sailors on the conning tower of a U-boat that has surfaced after sinking a British cargo ship during World War II). Survivors are seen in lifeboats. This 1941 painting is by German artist Adolf Bock (1890-1968) via Library of Congress.