Emerging Technologies Topic Week

By Ryan Fedasiuk

Since 2018, Indonesian fishermen have regularly reeled in autonomous, glider-like vehicles operating as far south as the Java Sea—part of China’s longstanding undersea vehicle research program first declassified in 2021. Over the past decade, details have sporadically emerged about China’s unmanned (UUV) and autonomous undersea vehicle (AUV) projects, but questions linger about which kinds of vessels the Chinese defense industry may be developing, and how the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might use them in a future conflict.

This article draws on a wide array of primary sources—including advertisements from defense companies, PLA writings and research papers, and information released by state-run research institutes—to illuminate China’s growing fleet of autonomous undersea vehicles. After profiling three major AUV research institutes, the article identifies potential applications of China’s growing fleet of AUVs and continued barriers to development.

China’s Big Three Undersea Vehicle Developers

As in many other Chinese technology industries, the state plays a leading role in undersea vehicle development. In 1986, Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang initiated the State High-Tech Development Plan (863 Plan) to fund billions of dollars in applied technology development. In 1996, marine technologies were added to the program, adding further fuel to China’s emerging undersea vehicle industry. In particular, three government-sponsored research institutions form the backbone of AUV development in China. Each began undersea vehicle research in the 1980s, and has gone on to pioneer lines of AUVs still in use today:

Shenyang Institute of Automation. Part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, SIA’s Computer Vision Group (机器人视觉组) is at the forefront of state-backed unmanned technology and autonomy research in China. In 1981, SIA developed the HR-01, China’s first remotely-piloted undersea vehicle. The institute went on to develop the “Explorer” (探索者) series of fully autonomous undersea vehicles in the 1990s and 2000s, with later variants capable of diving to 6,000 meters. Today, SIA specializes in developing prototypes of medium and large undersea vessels, including the Sea-Whale 2000 (海鲸2000) and Qianlong (潜龙; “Hidden Dragon”) series of AUVs.

China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation. As the world’s largest shipbuilding conglomerate, CSIC’s myriad research institutes have made significant contributions to China’s AUV research and development, particularly the 701, 702, 710, and 714 Research Institutes. Since 2000, CSIC has been responsible for developing the Haishen (海神; “Poseidon”) series of AUVs, in addition to a new line of autonomous undersea gliders, such as the Haiyi 1 (海翼一号; “Sea Wing”).

Harbin Engineering University. Originally called the Harbin Institute of Shipbuilding, HEU began developing a “Smart Water” (智水) series of AUVs in 1991, and has gradually expanded AUV testing in the South China Sea. The Smart Water series today comprises five variants of different sizes, but HEU has developed additional AUV models for undersea surveying and mapping, such as the Weilong (微龙; Microdragon) 1, 2, and 3. HEU is also home to China’s State Key Laboratory of Underwater Vehicle Technology (水下航行器信息技术重点实验室), which specializes in developing human-occupied, remotely-operated, and autonomous surface and deep-sea vehicles.

New Players in AUV Development

Beyond China’s big three AUV design centers, a growing number of research institutes and private enterprises are entering the Chinese AUV market. A document published in 2019 by the Chinese Society of Naval Architecture lists 159 undersea vehicle research projects under development at more than 40 Chinese universities—a significant increase over the 15 major universities that had constructed undersea vehicle research teams just four years prior. Another document prepared by Dr. Wu Jianguo, a professor at Hebei University of Science and Technology, shows that more than 48 universities and 45 enterprises in China host major UUV and AUV projects.

The CCP’s military-civil fusion (军民融合) development strategy is also facilitating a boom in China’s private-sector AUV industry. By promoting resource and information sharing between the military and private technology companies, China has seen some success in its efforts to accelerate AUV research, as several enterprises are developing new lines of AUVs independent of the big three research institutes. While it is too early to say whether they may become globally competitive with companies like the U.S.-based Bluefin Robotics or Norway’s Kongsberg, Chinese enterprises such as Xi’an Tianhe Haiphong Intelligent Technology (西安天和海防智能科技) and Startest Marine (星天海洋) seem to be emerging as China’s national champions of AUV systems and equipment. In 2017, China’s International Ocean Technology Exhibition in Qingdao attracted representatives from more than 500 enterprises working on AUV systems and components.

How the PLA Navy Might Use Autonomous Undersea Vehicles

While China’s AUV fleet still primarily consists of early-stage research experiments and prototypes, scientific research papers and theoretical writings by the PLA Navy (PLAN) indicate that it is primarily interested in using AUVs for marine surveying and reconnaissance, mine warfare and countermeasures, undersea cable inspection, and anti-submarine warfare. Each of these applications rely on different AUV models, and carry distinct implications and risks for the U.S. Navy and its partners in the Indo-Pacific.

Marine Surveying and Reconnaissance

The PLAN’s most mature application of AUVs is in marine surveying and reconnaissance. Chinese and American analysts have long assessed that the United States would retain a significant undersea advantage in a Taiwan Strait contingency, and the PLAN has rapidly expanded its manned diesel submarine force to compensate for this disadvantage. As early as 2013, the PLA commissioned construction of the Great Underwater Wall (水下长城), a network of hydrosonic sensors deployed at depths of 2,000 meters, which are designed to detect adversary undersea vehicles operating in the South China Sea. More recent research papers indicate that the PLAN may field groups of small and medium-sized AUVs for a similar purpose.

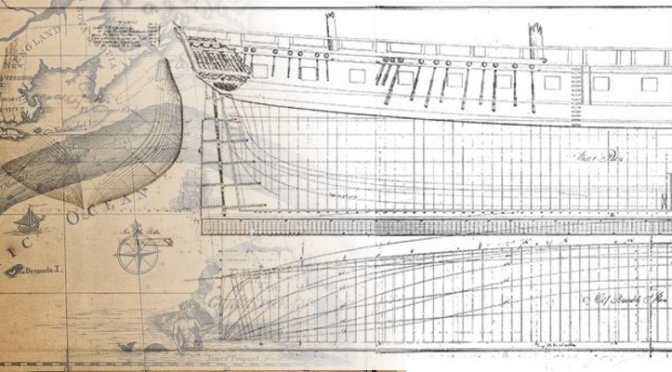

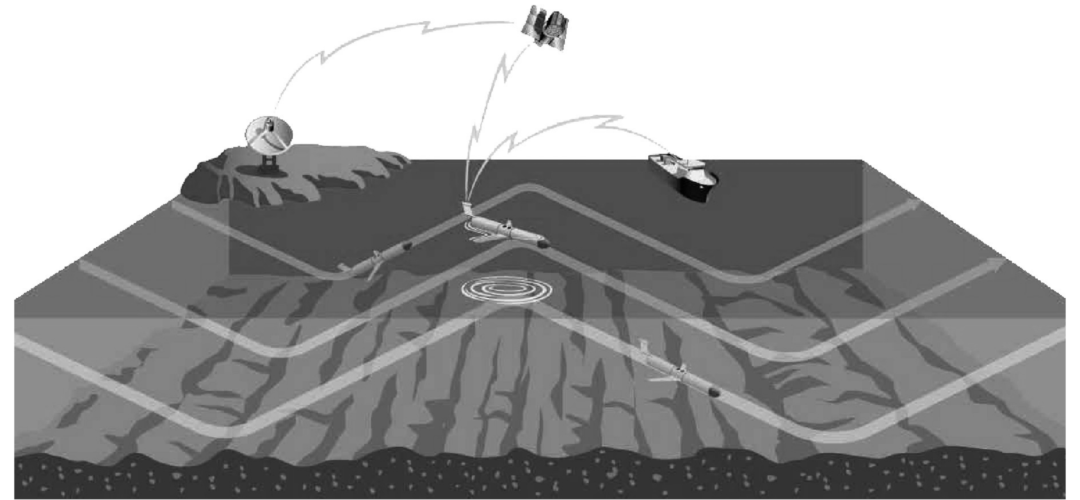

Portable and light models have so far formed the backbone of the PLAN’s emerging AUV fleet—in part due to battery constraints. Early AUV prototypes, such as CSIC’s Haishen 100 (海神100; “Poseidon 100”) and SIA’s Explorer (探索者), could dive to less than 1000 meters each; but modern variants have grown both in size and capability. Undersea gliders are a particularly promising innovation, and it is no surprise that so many have been found across the Indo-Pacific: Because of their improved range and endurance, gliders can more reliably detect undersea objects and periodically surface to transmit that information to ground stations and surface vessels. In the event of a crisis, analysts warn that autonomous gliders could be used to overcome China’s significant disadvantage in undersea warfare by detecting and tracking the locations of U.S. submarines even beyond the first island chain. Examples of such vehicles include SIA’s Haiyi (海翼; Sea Wing); Tianjin University’s Haiyan (海燕; Sea Swallow); and the Hai Xiang (海翔; Sea Flyer) developed by CSIC’s 702 Research Institute. Still, that gliders must surface in order to transmit information to one of three intelligence processing centers offers a point of vulnerability, and Chinese experts still believe the United States has an advantage in undersea surveying and mapping.

Figure 1. “Marine Environment Detection by Underwater Glider” Source: CSIC 714 Research Institute.

Mine Warfare and Countermeasures

Sea mines are a core tenet of Chinese naval doctrine and planning. As early as 2013, researchers at the China Engineering Science and Technology Forum publicly acknowledged the significance of UUVs in deploying mines and mine countermeasures (MCM); and military analysts have commented on the potential mine-laying capabilities of China’s HSU001 large-displacement UUV first unveiled in 2019. Today, the PLA may choose from more than 26 variants of floating and submerged mines designed to attack all manner of enemy ships and submarines.

Many of the PLA’s undersea mines are produced by CSIC’s 710 Research Institute—which also produces UUVs. Research published by the 710 Institute recommends developing AUVs and UUVs for minelaying and reconnaissance, but public information about the PLA’s current AUV models is scarce. One research paper published in August 2020 concludes that, “With the transformation of our navy’s strategy, the scope of anti-mine operations will extend to waters beyond the first island chain.” Some scholars believe that the PLAN could field more than 50 mines for each manned submersible—a feat that may eventually be possible for unmanned vehicles, too, as the Chinese AUV industry develops larger and larger vehicles. Examples of mid- and large-sized platforms include SIA’s Qianlong 1 and 2, and the Haishen series of UUVs developed by CSIC’s 701 Research Institute.

Figure 2. Haishen Series of AUVs. Source: Hebei University of Science and Technology.

Undersea Cable Inspection

Advances in unmanned vehicle research may also permit the PLAN to use AUVs to tap or sever undersea fiber-optic cables in a conflict, which concentrate near northern Taiwan. These cables are crucial not just for information dissemination in Taiwan, but also the trans-Pacific data exchanges that facilitate global internet access—including in some parts of the United States. HEU, for example, advertises AUVs for “underwater engineering investigation and maintenance,” including pipeline inspection and repair. Research papers and procurement records published by the PLA indicate that it may outfit undersea vehicles with robotic arms and sensors to interact with undersea cables. Some units have expressed an interest in procuring “SPICE,” a UUV produced by Kawasaki, which comes equipped with a robotic arm to repair undersea cables and pipelines.

Seabed Operations and Anti-Submarine Warfare

In the future, the Chinese military may use large AUV models for anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and operations near the seabed. Trends among PLAN research publications suggest that it is building signature libraries for undersea target detection and recognition, and several PLA units have awarded research contracts related to deep learning-based image recognition and target identification systems for undersea vehicles. In particular, students and researchers at HEU have pioneered an AI-based “seabed image mosaic system” for sonar image processing. Undersea target recognition systems like this could prove useful in autonomously identifying and interacting with sea floor infrastructure and other submarine vehicles.

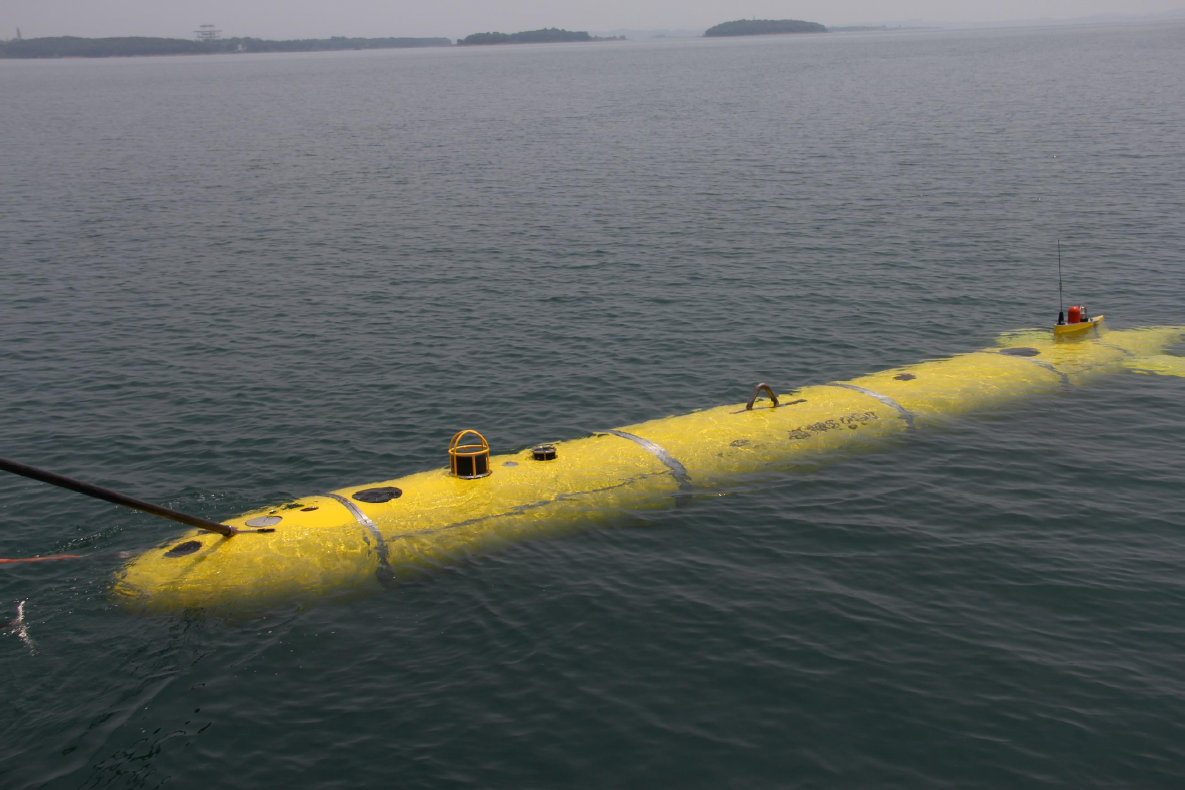

Large AUVs may also be outfitted with weapons to engage adversary submarines. To date, the Chinese defense industry has produced few large AUV models suitable for ASW, although the number is growing. One notable example is the HSU-001, a large-displacement vehicle that sports side-scanning sonar arrays and a magnetic anomaly detector. Other medium and large AUV prototypes set records for depth and distance in 2020, including SIA’s Haidou 1 (海斗一号) and Sea-Whale 2000. Weighing in at more than 3.5 tons, China’s largest AUV so far is the Haishen 6000 (海神6000; “Poseidon 6000”), a 25 foot-long prototype developed by CSIC’s 701 Research Institute. The system is apparently capable of diving to depths of 6,000 meters, and comes equipped with “multiple detection devices such as an ultra-short baseline positioning system, an aircraft black box search sonar array, deep-sea side scanning sonar, an underwater camera, and forward-looking sonar.” Neither the HSU001 nor the Haishen 6000 appear to be outfitted with mine-laying rails or other weapon systems, but further advances in large AUV models and battery life could permit them to carry such payloads.

Figure 3. Haishen 6000, China’s Largest Known AUV. Source: CSIC 710 Research Institute.

Barriers to Chinese AUV Development

Despite its demonstrable progress in undersea detection and navigation, the Chinese AUV industry still faces significant technical and bureaucratic barriers to developing undersea platforms for military use.

The largest barriers are technical—particularly battery life. Among the small, medium, and large AUV models catalogued in this paper, most cannot operate for more than 24 hours before they require refueling or recharging, and PLA officers expect U.S. military AUVs to suffer from similar limitations. Moreover, artificial intelligence is still an emerging technology, and the target recognition systems used in modern autonomous vehicles are not robust enough to reliably detect undersea targets, let alone engage them in combat. Despite the PLA’s progress in testing AUVs, research from the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) concludes that “the state of the current technology, the complexity of antisubmarine warfare, and the sheer scale and physics-based challenges of undersea sensing and communications all suggest these systems have a long way to go.”

Bureaucratic inertia and a culture of central planning also constrain China’s progress in undersea vehicle development. On the one hand, the CCP’s continued focus on military-civil fusion does seem to be alleviating some barriers to AI development in the public sector. For example, a catalogue of ocean engineering projects published by the Tianjin Municipal Government advertises dozens of AUV and UUV models for both civilian and military use. But the fact remains that the big three state-backed research institutes—SIA, CSIC, and HEU—still dominate AUV development, and private-sector innovation in China has not yet reached its full potential.

Ryan Fedasiuk is a Research Analyst at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). His work focuses on military applications of emerging technologies, and on China’s efforts to acquire foreign technical information.

Featured Image: PLA HSU001 large-displacement UUV at Chinese Military Parade, October 2019. (Public domain)