Until recently, it was hard to imagine Sweden joining NATO. With long traditions of neutrality, Sweden and Finland had distanced themselves from the main military centers of Europe. The reason for neutrality is succinctly explained in the introduction to the book Navies in Northern Waters 1721-2000: “The present situation is a further illustration of the long-standing conflict between the legal and power-oriented approaches to disputes in the region,” with the Swedes and Finns aligned with the former. In 1994 Sweden joined Partnership for Peace (PfP) as a framework to cooperate with NATO. Still insisting on its place as a militarily non-aligned country, the Swedish Mission to NATO states that “by participating in PfP, Sweden wishes to contribute to the construction of a Euro-Atlantic structure for a safer and more secure Europe.”

Public Swedish support for joining NATO remained limited, with about 50% against as of mid-April, but supporters of this idea increased their share from 17% to 29% last year alone. In the same article we find important opinion of Finland’s Prime Minister Jyrki Katainen who said “that both Finland and Sweden should consider joining Nato when the time is right.” A small Finnish step in this direction is that this year the nation agreed to a Memorandum of Understanding with NATO, while Sweden and Finland are increasing military cooperation with each other under a landmark pact. So what caused both Nordic countries to begin reevaluate their positions? Prof. Mearsheimer in his book The Tragedy of Great Power Politics wrote:

When a state surveys its environment to determine which states pose a threat to its survival, it focuses mainly on the offensive capabilities of potential rival, not their intentions.

Living near mighty military power means that one lives in a state of permanent insecurity, so what one hopes for are benign intentions. The war in Georgia ignited doubt about one particular neighbor, but Ukraine has forced caution to give way to fear. If one can’t hide by flying “under the radar” of a big power, then what remains is to ally with another power. Appeasement doesn’t have a good track record during Europe’s last 100 years. But as Jan Joel Andersson explains in the Foreign Affairs article “Nordic NATO,” both countries need public buy-in for the solution before joining the Alliance. Although skeptical, Scandinavians seem to slowly appreciate this path and support for the idea is growing. The article lists good arguments, both political and military, for Sweden and Finland to join NATO from the Alliance’s perspective. In fact, this would be a geostrategic loss for Russia, greater probably than the gain of Crimea. From a purely military point of view, the following excerpt is critical for understanding the regional stability the additions would aid:

Even more important, Sweden and Finland’s formal inclusion in the alliance would finally allow NATO to treat the entire Arctic-Nordic-Baltic region as one integrated military-strategic area for defense planning and logistical purposes, which would make the alliance much more able to defend Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania against Russia.

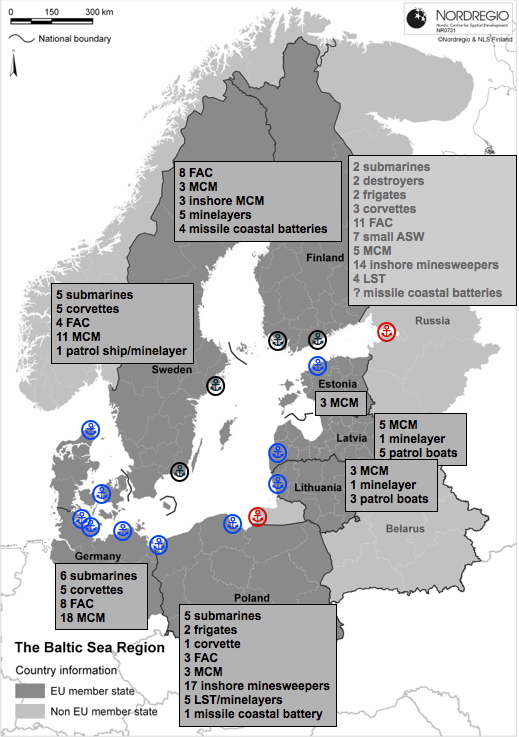

It’s worthwhile to take a look at a map, especially to highlight the maritime and naval aspects of this story.

In the current situation, the Baltics represent a relatively narrow strip of land, lightly defended and not offering defense-in-depth. Any sustained reinforcements could come only from sea, which would require sea control. The main NATO naval forces would likely operate from bases in Germany and Swinoujscie in western Poland, as Gdynia and Klajpeda could be put at risk by ground operations. Although it would be possible to organize a successful blockade of any opposing naval forces using the Alliance advantage in submarines, light surface forces would have tough time overcoming land-based air forces and coastal batteries. Using Adm. J.C. Wylie’s terminology, the geography of the region strongly favors sequential warfare on land instead of cumulative naval warfare for which there would be no time assuming the desire to defend the Baltics.

Swedish access to NATO would alter these considerations significantly, bringing a few additional benefits to the more-realistic defense of the Baltics:

- Norway would no longer be an “isolated” NATO member, as its depth of defense increases.

- Baltic Sea control could be achieved and maintained by local navies with limited support from the United States.

There are two other aspects to consider, however. For Finland, Sweden’s joining NATO would only increase its isolation as the only neutral country in the region. The preference for a sequential land warfare strategy would expose Finland for greater risk. The situation would not be so different from that of the Black Sea. Therefore the best would be a common decision of both Sweden and Finland, even if it complicates matters.It is difficult to imagine synchronization of political willingness in such sensitive area, but growing cooperation between Nordic countries could be helpful. Nordic Defence Cooperation initiative, including Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark and Iceland, although mostly focused on military efficiency includes already mix of NATO and EU countries, and active participation of both Finland and Sweden with NATO lower technical barriers of access. The key point remains public support for such idea, but as it was mentioned already, such support and acceptance seems to slowly grow.

Another issue is the opportunity to evaluate/reevaluate the concept of the U.S. Navy’s littoral combat ship (LCS) and/or its successor in the Baltic Sea security environment. Two different scenarios including Nordic countries offer very different operational possibilities. In today’s state of things, the LCS lacks offensive power of anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM). Meanwhile, pondering anti-air defense leads to the dilemma the best defined by Swedish designers of the Visby corvette – “invincible or invisible”. However, in the case of the Nordic countries belonging to NATO, LCS’s anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and mine counter-measure (MCM) capabilities would be very much appreciated. In the May issue of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings, Adm. Walter E. Carter offers some remarks on future forces in his article “Sea Power in the Precision-Missile Age:”

Another issue is the opportunity to evaluate/reevaluate the concept of the U.S. Navy’s littoral combat ship (LCS) and/or its successor in the Baltic Sea security environment. Two different scenarios including Nordic countries offer very different operational possibilities. In today’s state of things, the LCS lacks offensive power of anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM). Meanwhile, pondering anti-air defense leads to the dilemma the best defined by Swedish designers of the Visby corvette – “invincible or invisible”. However, in the case of the Nordic countries belonging to NATO, LCS’s anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and mine counter-measure (MCM) capabilities would be very much appreciated. In the May issue of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings, Adm. Walter E. Carter offers some remarks on future forces in his article “Sea Power in the Precision-Missile Age:”

Based on the preceding analysis, it appears that the most significant forces for future warfare at sea include:

- Platforms employing standoff ordinance that penetrate high-end defenses;

- Platforms with an emphasis on offensive firepower to prevail at sea;

- Mobile and low-observable platforms and logistics, readily dispersed, and heavily protected or hidden by decoys, obscurants, RF jammers, and signature control; and

- Forces minimally reliant on RF networks to be employed against high-end opponents using pre-planned responses and low-data-rate, secure, and sporadic communications.

Conversely, less relevant forces of the future will include:

-

Those dependent on fixed bases;

-

Platforms within enemy missile ranges that have large signatures and are thus readily targetable;

-

Systems dependent upon long-distance, high-data-rate RF networks;

-

Platforms that must penetrate high-end defenses to deliver ordnance; and

-

Platforms whose primary means of survival rests on active defense (i.e. shooting missiles with missiles).

While this analysis seems to be a perfect description of Pacific scenarios, a narrow sea like the Baltic invites further elaboration as this environment offers little room for stand-off or escape from inference from shore based-capabilities. Striking an enemy’s shore would incentivize small, stealthy, and unmanned platforms, but keeping sea lines of communications open in the same area would be difficult without classic surface forces. So the question remains open as to how survivable these light surface forces would be in restricted waters. And in the case of submarines the weak point in narrow waters is still the naval base from which they operate.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is the context, purpose, and structure of navies – and promoting discussion on these subjects in his country.