5th and final post in our series on 3D printing.

3D printing revolutionizes the supply chain by removing the need for many specific parts, but it still lacks true independence due to the need for “toner.” If necessary, a soldier in the field can pick up the weapon of his neutralized enemy and use it to continue the fight, but the wreckage of war is often left to rot, useless for more than cover. However, the great material waste found in war can generate immense new capabilities when combined with 3D printing’s need for raw materials.

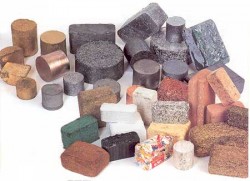

In the further future, the commander’s greatest source of raw materials for his new 3D printing capability will be the wreckage of the battlefield and waste from his own operations. Everything from the valuable copper in rubble to the wreckage of destroyed vehicles. In most cases, materials can be collected whole: tanks, humvees, burnt-out trucks, bullet casings. Obsolete or worn equipment can be harvested for its raw materials and re-forged into new product. Modern composite weapons can be smashed, damaged, or past their service life; thrown back into the “stock material,” and recycled into a new rifle. Battlefield clearance, broken weapons, and ruined equipment stop being a hindrance and start becoming potential resources for the commander armed with 3D printing.

Whatever cannot be easily ground down and re-purposed can be leached out and re-used. Biomining is the process by which natural and engineered bacteria are used to collect raw material. Industrial-scale use of bacteria to make product is not revolutionary. Beer is the oldest, and perhaps most delicious example that comes to mind for the industrial use of bacteria. Soon we might start using it for fuel. Biomining is already used to leach minerals from low-grade ores, it could potentially salvage materials from rubble or severely degraded equipment.

The direct applications to maritime operations are especially evident for landing operations and damage control. Amphibious landings are always made more precarious by the supply situation, logistics’ tenuous reach to a force on the shore that could potentially be pushed into the sea. With the ability to re-purpose his surrounding environment: cars, computers, telephone wires, etc… a landing force no longer need wait for guns, vehicles, parts, or replacement equipment when these things can be resurrected from wreckage or indigenous infrastructure. At sea, battle-damaged ships can re-forge equipment out of the destroyed material. Imagine if the USS Cole had a 3D printing capability, giving it the ability to replace without restriction any number of critical systems. These ideas only scratch the surface. As the logistics, shape, and field operations of all military forces profoundly transform, not only will our weapons change, but the way we fight will transform with this newfound flexibility and independence.

Matt Hipple is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.