By Ching Chang

Introduction

In the past few months, the Korean Peninsula has once again become the focus of security challenges in the Asia-Pacific. Accompanied with the unstable political situation after the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye, unanimously passed by the Republic of Korean Constitutional Court on March 10, 2017, Pyongyang decided to conduct a series of military exercises and a sixth nuclear test, making regional stability even worse.

The Republic of Korea and the United States of America started the annual military exercises known as Key Resolve and Foal Eagle in order to deter any North Korean adventurism before the next president was elected in mid-May. Simultaneously with the emerging crisis in the Korean peninsula, a dramatic summit between Beijing and Washington was held in early April. Donald Trump and Xi Jinping exchanged their perspectives on the Korean Peninsula at the Mar-a-Lago estate, though no clear and conclusive approach reached a consensus during this meeting.

Many observers had predicted that an imminent conflict may erupt then simply because both United States and North Korea had shown their forces in such a high profile manner. Nonetheless, some still argued that there was no possibility of any armed conflict since no signal of real war preparation ever appeared. Furthermore, all U.S.-ROK annual joint exercises are conducted with proper scales. No particular alert poise and combat readiness may prove any attempt to solve the North Korean threats with military contingency maneuvers. As the situation around the Korean Peninsula returns to normal now, we should reevaluate the Korean Peninsula crisis in order to identify where the misperceptions are that lead us to an overstatement of the reality in North Korea.

Strategic Dimensions of A Nuclear DPRK

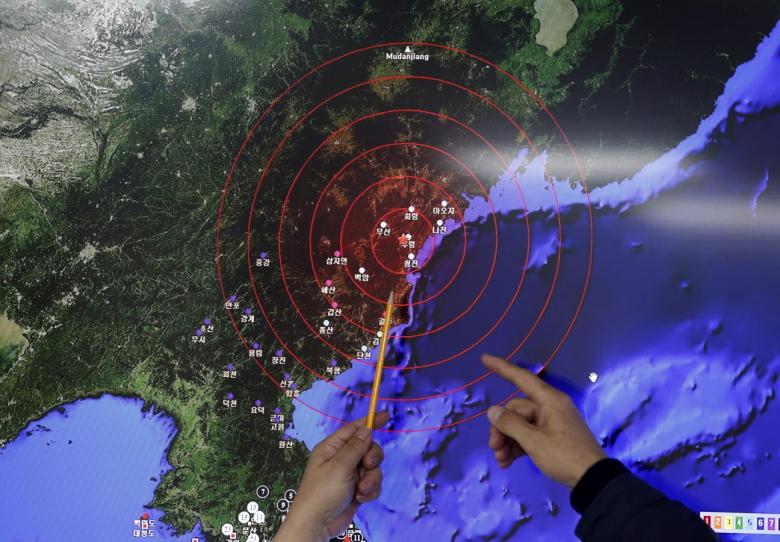

First, how serious is the challenge that can be brought by the North Korean missile and nuclear program? Since 2006, Pyongyang has successfully conducted nuclear tests five times. Unquestionably, the North Korean regime can be defined as nuclear-capable. Nonetheless, we should not automatically assume that Kim Jong-un already owns any reliable nuclear weapon. We should remember that conducting a nuclear test in a well-managed underground facility is one thing; acquiring reliable nuclear weapons with a delivery vehicle through the weaponization process is another issue.

Key questions abound. Does a nuclear test and a missile test necessarily indicate a mature nuclear missile? Did Pyongyang ever prove that it has successfully completed the weaponization process from its primitive nuclear test yet? Can nuclear tests that happened in 2006, 2009, 2013 and twice in 2016 be sufficient to prove that North Korea may already own a mature nuclear weapon and the associated delivery vehicle? Do we need to review the historical records of various nuclear powers who developed their own nuclear arsenals? Is it unrealistic to assume that North Korea is capable of completing the weaponization process based on only a few tests? Even if North Korea has the luck to complete the weaponization process of its nuclear warheads and delivery vehicles within such a short period of time, has Pyongyang established a credible nuclear force yet?

A well-articulated nuclear force is far more complicated than simply establishing a military force with nuclear weapons and delivery tools. The investment of command and control mechanisms that are compatible with the nuclear strategy may consume more of a budget than the nuclear weapon systems themselves. Force protection facilities and special forces for protecting the nuclear arsenal as well as other nuclear-related establishments are vital investments to build a mature nuclear force. We have already seen in the case of Pakistan and India how hard it is for them to retain their credibility of nuclear deterrence after their own nuclear tests. Arguably, we may also speculate that Pyongyang so far is only nuclear-capable, but to have any reliable nuclear arsenal and credible nuclear force, we have still yet to see.

Second, we should ask how North Korean nuclear capacity may convert into any political influence. It is very hard to see if Kim’s regime may use the nuclear weapon as a coercive means to take any offensive actions towards neighboring states. Has Pyongyang ever mentioned that the nuclear weapon will be used other than self-defense? Can North Korea afford a first-strike nuclear strategy? We should reconsider the purpose of Kim’s nuclear policy instead of misconstruing his real intention. Is a nuclear weapon a good choice to enhance the legitimacy of the government, thus assuring the political survivability of the regime? Given the case of the former Soviet Union, the answer is not ideal for Kim Jong-un. Can the nuclear arsenal enhance the political legitimacy of the North Korean government? This answer may also be disappointing. Kim’s nuclear policy has a very slim probability of reshaping the power structure in Northeast Asia and supporting the political survival of Kim’s regime. We should make no mistake in mistaking North Korea’s nuclear weapon for Iran’s anti-ship missile, which can immensely affect maritime transportation at the exit of the Persian Gulf. The nuclear weapons held by the North Korean may not have the same influence as other military assets in Kim’s hands, such as the hundreds of conventional artillery assets proximate to Seoul.

https://gfycat.com/AromaticDisguisedCrab

North Korea has carried out massive artillery drills, possibly the largest in the country’s history, to mark the 85th anniversary of the founding of the country’s Army. (KCNA)

The China Factor

Third, the China factor in the Korean Peninsula should be clearly identified. There is much speculation on Beijing’s position towards Pyongyang. Undeniably, China is the only key ally to this isolated state. Nevertheless, the influence of China on North Korea is also limited. China has clearly addressed its position on the North Korean nuclear issue with several statements noted by the Chinese governmental white paper titled China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation issued on January 11, 2017. It first admitted that “The nuclear issue on the Korean Peninsula is complex and sensitive …” which proves that managing a nuclear Korean Peninsula is a daunting challenge to Beijing, too. Unlike many accusations of China secretly helping Pyongyang develop its nuclear arsenal, this policy statement clearly indicated China’s disagreement with the existence of North Korea’s nuclear capability.

Moreover, China also clearly expressed the willingness to cooperate with the United States on this issue, stating “China has actively pushed for peaceful solutions to hotspot issues such as the nuclear issue on the Korean Peninsula and the Afghanistan issue, and played its due role as a responsible major country” and that, “The two countries have made steady progress in practical cooperation in various fields, and maintained close communication and coordination on major regional and global issues like climate change, the Korean and Iranian nuclear issues, Syria, and Afghanistan.” We, therefore, should remember that the Mar-a-Lago summit is not a starting point for the U.S.-PRC cooperation on the North Korean nuclear issue, but a reaffirmation of positions. More importantly, it makes the following statement:

“China is committed to the denuclearization of the peninsula, its peace and stability, and settlement of the issue through dialogue and consultation. Over the years, China has made tremendous efforts to facilitate the process of denuclearization of the peninsula, safeguard the overall peace and stability there, and realize an early resumption of the Six-Party Talks… the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) conducted two nuclear tests and launched missiles of various types, violating UN Security Council resolutions and running counter to the wishes of the international community. China has made clear its opposition to such actions and supported the relevant Security Council resolutions to prevent the DPRK’s further pursuit of nuclear weapons…other parties concerned should not give up the efforts to resume talks or their responsibilities to safeguard peace and stability on the peninsula.”

We, therefore, may conclude with a clear picture of China’s position on Pyongyang’s nuclear adventurism.

However, it is necessary to remember another issue: the deployment of the THAAD missile system in the Korean Peninsula in recent months. Although Beijing hasn’t linked this issue with the North Korean nuclear issue yet, Washington should be aware of the sensitivity of this military maneuver. Given that the white paper states “Despite clear opposition from relevant countries including China, the U.S. and the Republic of Korea (ROK) announced the decision to start and accelerate the deployment of the THAAD anti-ballistic missile system in the ROK. Such an act would seriously damage the regional strategic balance and the strategic security interests of China and other countries in the region, and run counter to the efforts for maintaining peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula. China firmly opposes the U.S. and ROK deployment of the THAAD anti-ballistic missile system in the ROK, and strongly urges the U.S. and the ROK to stop this process.” Of course, the newly-elected South Korean President Moon Jae-in may have the possibility to change the decision of deploying the THAAD system. Nonetheless, Washington should consider how these two issues can be well-managed together before any linkage actually emerges in Beijing’s strategic calculus in the future.

China-DPRK Treaty Ties

Last but not least, during past several months, there has been a missing point rarely noted in commentary. The Sino-North Korean Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty signed on July 11, 1961 is still a valid security assurance granted by Beijing so far. Article Two is a provision of mutual military assistance in the event of security threats to either signatory. The phrases of assuring military intervention as “The two parties undertake jointly to adopt all measures to prevent aggression against either party by any state,” and “in the event of one of the parties being subjected to the armed attack by any state or several states together and thus being involved in a state of war, the other party shall immediately render military and other assistance by all means at its disposal,” gave the treaty characteristics of a pact for security alliance.

Also, Article Three notes, “Neither party shall conclude any alliance directed against the other party or take part in any bloc or in any action or measure directed against the other party,” which can possibly exclude the possibility of Beijing granting tacit consent to Washington for any military maneuver involving the decapitation of North Korean leadership or the destruction of its nuclear facilities with military strikes. Although it is very unrealistic to argue that the Article Three of this treaty may effectively restrict any cooperative diplomatic effort between Washington and Beijing towards Pyongyang, it is necessary to understand Beijing’s present position of interpreting the terms noted in this treaty.

Conclusion

The Korean Peninsula crisis will never be the catalyst for improving Sino-US relations, though both parties do share the concern of future development. There are so many issues on the mutual relations agenda between Washington and Beijing. On the other hand, the Korean Peninsula crisis is the best chance for the Japanese Abe’s regime to have an excuse to revise its constitution. For the Japanese concern on the Korean Peninsula is a “just cause” or only a “just because”, the strategy planners in Washington should well assess its significances. With many misconceptions already existing on the Korean Peninsula, the most valuable advice would be “always be aware of those who intend to fish in troubled waters”. Before taking prompt decisions and taking the viewpoints from media commentary, reviewing all the basic documents carefully should also be an essential element for formulating future policies.

Dr. Ching Chang was a line officer in the Republic of China Navy for more than thirty years. As a visiting faculty member of the China Military Studies Masters Program at the National Defense University, ROC, he is recognized as a leading expert on the People’s Liberation Army with unique insights on its military thinkings.

Featured Image: A North Korean soldier watches the South Korean side at the truce village of Panmunjom in the demilitarized zone separating the two Koreas in Paju, north of Seoul April 4, 2013. (Reuters/Lee Jung-hoon/Yonhap)