By LT Kaitlin Smith

The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program has been subjected to heavy scrutiny, and much of it is justified. What is getting lost in the discourse is the real capability that LCS provides to the fleet. From my perspective as an active duty service member who may be stationed on an LCS in the future, I’m more interested in exploring how we can employ LCS to utilize its strengths, even as we seek to improve them. Regardless of the program’s setbacks, LCS is in the Fleet today, getting underway, and deploying overseas. Under the operational concept of distributed lethality, LCS both fills a void and serves as an asset to a distributed and lethal surface force in terms of capacity and capability.

Capacity, Flexibility, Lethality

The original Concept of Operations written by Naval Warfare Development Command in February 2003 described LCS as a forward-deployed, theater-based component of a distributed force that can execute missions in anti-submarine warfare, surface warfare, and mine warfare in the littorals. This concept still reflects the Navy’s needs today. We urgently need small surface combatants to replace the aging Avenger-class mine countermeasure ships and Cyclone-class patrol craft, as well as the decommissioned Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates. Capacity matters, and “sometimes, capacity is a capability” in its own right. We need gray hulls to fulfill the missions of the old frigates, minesweepers and patrol craft, and until a plan is introduced for the next small surface combatant, LCS will fill these widening gaps.

LCS was also envisioned as a platform for “mobility” related missions like support for Special Operations Forces, maritime interception operations, force protection, humanitarian assistance, logistics, medical support, and non-combatant evacuation operations. Assigning these missions to LCS frees up multimission destroyers and cruisers for high-end combat operations. We’ve already seen how LCS can support fleet objectives during the deployments of USS FREEDOM (LCS 1) and USS FORT WORTH (LCS 3). Both ships supported theater security operations and international partnerships with Pacific nations through participation in the Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) exercise series. USS FREEDOM conducted humanitarian and disaster response operations following the typhoon in the Philippines, and USS FORT WORTH conducted search and rescue operations for AirAsia flight QZ8501. The forward deployment of the ships to Singapore allowed for rapid response to real-world events, while allowing large surface combatants in the region to remain on station for their own tasking. With an 11-meter rigid hull inflatable boat onboard, LCS is well-suited to conduct visit, board, search, and seizure missions in Southeast Asia to combat piracy and protect sea lanes.

The presence of more ships on station doesn’t just allow us to fulfill more mission objectives; capacity also enables us to execute distributed lethality for offensive sea control. One of the goals of distributed lethality is to distribute offensive capability geographically. When there are physically more targets to worry about, that complicates an enemy’s ability to target our force. It also allows us to hold the enemy’s assets at risk from more attack angles.

The other goals of distributed lethality are to increase offensive lethality and enhance defensive capability. The Fleet can make the LCS a greater offensive threat by adding an over-the-horizon missile that can use targeting data transmitted to the ship from other combatants or unmanned systems. In terms of defensive capability, LCS wasn’t designed to stand and fight through a protracted battle. Instead, the Navy can increase the survivability of LCS by reducing its vulnerability through enhancements to its electronic warfare suite and countermeasure systems.

LCS may not be as survivable as a guided missile destroyer in terms of its ability to take a missile hit and keep fighting, but it has more defensive capability than the platforms it is designed to replace. With a maximum speed of over 40 knots, LCS is more maneuverable than the mine countermeasure ships (max speed 14 kts), patrol craft (max speed 35 kts), and the frigates (30 kts) it is replacing in the fleet, as well as more protective firepower with the installation of Rolling Airframe Missile for surface-to-air point defense. Until a plan has been established for future surface combatants, we need to continue building LCS as “the original warfighting role envisioned for the LCS remains both valid and vital.”

New Possibilities

LCS already has the capability to serve as a launch platform for MH-60R helicopters and MQ-8B FireScout drones to add air assets to the fight for antisubmarine warfare and surface warfare operations. LCS even exceeds the capability of some DDGs in this regard, since the original LCS design was modified to accommodate a permanent air detachment and Flight I DDGs can only launch and recover air assets.

We have a few more years to wait before the rest of the undersea warfare capabilities of LCS will be operational, but the potential for surface ship antisubmarine warfare is substantial. A sonar suite comprised of a multifunction towed array and variable depth sonar will greatly expand the ability of the surface force to strategically employ sensors in a way that exploits the acoustic environment of the undersea domain. LCS ships with the surface module installed will soon have the capability to launch Longbow Hellfire surface-to-surface missiles. The mine warfare module, when complete, will provide LCS with full spectrum mine warfare capabilities so that they can replace the Avenger class MCMs, which are approaching the end of their service life. Through LCS, we will be adding a depth to our surface ship antisubmarine warfare capability, adding offensive surface weapons to enable sea control, and enhancing our minehunting and minesweeping suite. In 2019, construction will begin on the modified-LCS frigates, which will have even more robust changes to the original LCS design to make the platform more lethal and survivable.

The light weight and small size of LCS also has tactical application in specific geographic regions that limit the presence of foreign warships by tonnage. Where Arleigh Burke-class destroyers weigh 8,230 to 9,700 tons, the variants of LCS weigh in from 3,200 to 3,450 tons. This gives us a lot more flexibility to project power in areas like the Black Sea, where aggregate tonnage for warships from foreign countries is limited to 30,000 tons. True to its name, LCS can operate much more easily in the littorals with a draft of about 14-15 feet, compared to roughly 31 feet for DDGs. These characteristics will also aid LCS’s performance in the Arabian Gulf and in the Pacific.

Of course, any LCS critic might say that all this capability and potential can only be realized if the ships’ engineering plants are sound. My objective here is not to deny the engineering issues—they get plenty of press attention on their own—but to highlight why we’ll lose more as a Navy in cutting the program than by taking action to resolve program issues. It’s worth mentioning that the spotlight on LCS is particularly bright. LCS is not the only ship class that experiences engineering casualties, but LCS casualties are much more heavily reported in the news than casualties that occur on more established ship classes.

Conclusion

LCS was designed as one part of a “dispersed, netted, and operationally agile fleet,” and that’s exactly what we need in the fleet today to build operational distributed lethality to enable sea control. Certainly, we need to address the current engineering concerns with LCS in order to project these capabilities. To fully realize the potential of the LCS program, Congress must continue to fund LCS, and Navy leaders must continue to support the program with appropriate manning, training and equipment.

LT Nicole Uchida contributed to this article.

LT Kaitlin Smith is a Surface Warfare Officer stationed on the OPNAV Staff. The opinions and views expressed in this post are hers alone and are presented in her personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

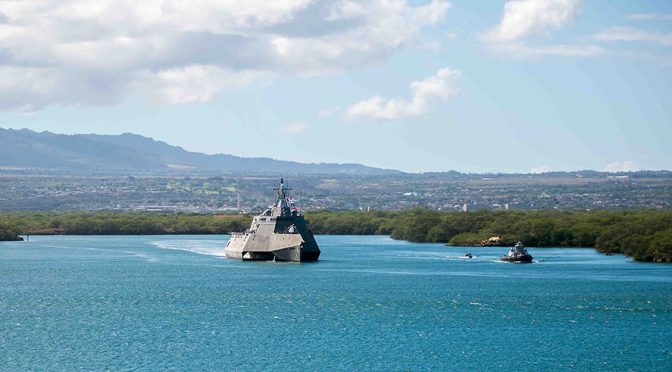

Featured Image: PEARL HARBOR (July 12, 2016) – The littoral combat ship USS Coronado (LCS 4) transits the waters of Pearl Harbor during RIMPAC 2016. (U.S. Navy photo by MC2 Ryan J. Batchelder/Released)