Guest post for UUV Week by Steve Weintz.

As potential adversaries sharpen their abilities to deny U.S. forces the freedom to maneuver, they concurrently constrain America’s traditional strength in supporting expeditionary power. Sea-bases bring the logistical “tail” closer to the expeditionary “teeth,” but they must stay outside the reach of A2/AD threats. Submarines remain the stealthiest military platform and will likely remain so for some time to come. In addition to their counter-force and counter-logistics roles, subs have seen limited service as stealth cargo vessels. History demonstrates both the advantages and limitations of submarines as transports. Submarine troop carriers, such as those used in SOF operations, are distinct from submarine freighters; the submarine’s role in supply and sustainment is addressed here. Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) will revolutionize minesweeping, intelligence collection, and reconnaissance. But they may also finally deliver on the century-old promise of the submarine as a stealthy logistics platform.

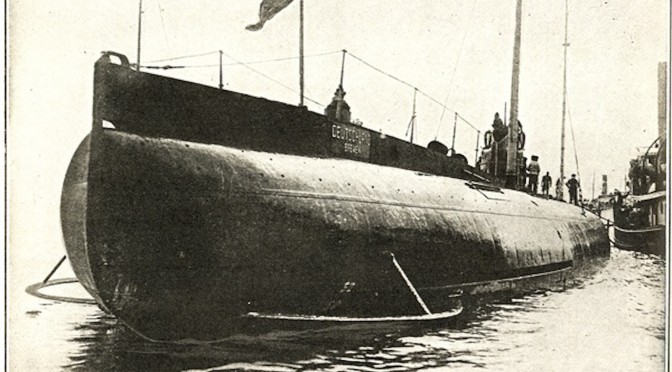

Although early submarine pioneers like Simon Lake saw commercial advantage in subs’ ability to avoid storms and ice, submarines as cargo carriers were first used operationally to counter Britain’s A2/AD strategy against Germany in World War I. The Deutschland and her sister boat Bremen were to be the first of a fleet of submarine blockade-runners whose cargo would sustain the German war effort. Despite her limited payload – only 700 tons – the privately-built Deutschland paid for herself and proved her design concept with her first voyage. But the loss of Bremen and America’s turn against Germany scuttled the project.

Cargo subs were again employed in World War II. The “Yanagi” missions successfully transported strategic materials, key personnel, and advanced technology between Germany and Japan. The Japanese also built and used subs to resupply their island garrisons when Allied forces cut off surface traffic. Their efforts met with limited success – enough to continue subsequent missions but not enough to shift the outcome of the Allied strategy. The Soviet Union also used submarines to sustain forces inside denied areas at Sevastopol and elsewhere. These efforts inspired serious consideration of submarine transports that carried over well into the Cold War. Soviet designers produced detailed concepts for “submarine LSTs” capable of stealthily deploying armor, troops and even aircraft.

Dr. Dwight Messimer, an authority on the Deutschland, points out that cargo subs – with one notable exception – have never really surmounted two key challenges. They have limited capacity compared with surface transports, and their cost and complexity are far greater. If subs are made larger for greater capacity, they forfeit maneuverability, submergence speed, and stealth. If built in greater numbers their expense crowds out other necessary warship construction. The Deutschland and Japan’s large transport subs handled poorly and were vulnerable to anti-submarine attacks. Many cargo subs were converted into attack subs to replace attack-sub losses.

The one notable exception to these difficulties is “cocaine subs” so

frequently encountered by the US Coast Guard. These rudimentary stealth transports are simple and inexpensive enough to construct in austere anchorages, make little allowance for crew comfort, and have proven successful in penetrating denied US waters. The tremendous value of their cargoes means that only a few of these semi-subs need to run the blockade for their owners’ strategy to succeed.

Logistical submarine designers could potentially overcome their two primary challenges by drawing inspiration from smugglers and from nature. UUVs, like other unmanned platforms, enjoy the advantages gained by dispensing with crew accommodations or life-support

equipment. Large UUVs built and deployed in large numbers, like cocaine subs and pods of whales, could transport useful volumes of cargo in stealth across vast distances. MSubs’ Mobile Anti-Submarine Training Target (MASTT), currently the largest UUV afloat, offers a glimpse at what such UUVs might look like. At 60 metric tons and 24 meters in length, MASTT is huge by UUV standards but very small compared to most manned subs.

3D printing technology is rapidly expanding, producing larger objects from tougher, more durable materials. Already, prototype systems can print multistory concrete structures and rocket engines made of advanced alloys. It will soon be possible to print large UUV hulls of requisite strength and size in large numbers. Indeed, printed sub and boat hulls were one of the first applications conceived for large-scale 3D printing. Their propulsion systems and guidance systems need not be extremely complex. Scaled-down diesel and air-independent propulsion systems, again mass-produced, should suffice to power such large UUVs. These long-endurance mini-subs would notionally be large enough to accommodate such power-plants.

10 large UUVs of 30 tons’ payload each could autonomously deliver 300 tons of supplies to forward positions in denied areas. 300 tons, while not a great deal in comparison to the “iron mountain” of traditional American military logistics, is nevertheless as much as 5 un-stealthy LCM-8s can deliver.

A “pod” of such UUVs could sail submerged from San Diego, recharging at night on the surface, stop at Pearl Harbor for refueling and continue on their own to forward bases in the Western Pacific.

Their destinations could be sea-bases, SSNs and SSGNs, or special forces units inserted onto remote islands. Cargoes could include food, ammunition, batteries, spare parts, mission-critical equipment, and medical supplies. In all these cases, a need for stealthy logistics – the need to hide the “tail” – would call for sub replenishment versus traditional surface resupply. Depending on the mission, large UUVs could be configured to rendezvous with submerged subs, cache themselves on shallow bottoms, or run aground on beaches. Docking collars similar to those used on deep-submergence rescue vehicles could permit submerged dry transfer of cargo. UUVs could also serve as stealthy ship-to-shore connectors; inflatable lighters and boats could be used to unload surfaced UUVs at night.

When confronted with anti-submarine attacks a “pod” or convoy of such UUVs could submerge and scatter, increasing the likelihood of at least a portion of their cumulative payload arriving at its destination. Some large UUVs in such a “pod” could carry anti-air and anti-ship armament for defense in place of cargo, but such protection entails larger discussions about armed seaborne drones.

A submarine – even a manned nuclear submarine – is not the platform of choice if speed is essential. Airborne resupply can deliver cargoes much more quickly. But not all cargoes need arrive swiftly. The water may always be more opaque than the sky, and larger payloads can be floated than flown. It remains to be seen if large stealthy unmanned transport aircraft can be developed.

While these notions seem fanciful there is nothing about the technology or the concept beyond the current state of the art. Large numbers of unmanned mini-subs could overcome both the capacity and expense limitations that limited the cargo submarine concept in the past. The ability to stealthily supply naval expeditionary forces despite A2/AD opposition would be a powerful force multiplier.