Regional Strategies Topic Week

By Capt. Andrew Norris, J.D., USCG (ret.) and Alexander Norris

Introduction

For the past several years, Turkey has leveraged its regional economic, political, and military superiority to aggressively assert a claim over contested, potentially oil-rich regions of the Eastern Mediterranean. This hegemonic strategy, domestically referred to as “Mavi Vatan,” or “blue homeland,” has most recently manifested itself in Turkey’s deployment of the seismic vessel Oruç Reis with a naval escort to disputed waters south and west of Cyprus. Despite widespread and growing international criticism of this doctrine and its associated activities, Turkey has so far remained steadfast in its resolve. This was exemplified by Turkish Navy Commander Engin Ağmış’ recent pronouncement, spoken in the presence of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdogan,* that “[w]e are proud to wave our glorious Turkish banner in all our seas. . . I submit that we are ready to protect every swath of our 462 thousand square kilometer blue homeland with great determination and undertake every possible duty that may come.” The impacts of Turkey’s “blue homeland” doctrine and associated activities to regional security deserve closer scrutiny, as well as the likelihood of Turkey’s current policies allowing it to achieve its strategic “Mavi Vatan” goals.

Mavi Vatan and Associated Maritime Activities

Turkey’s “Mavi Vatan” strategy is conceived as a means of ending Turkey’s near-complete dependence on foreign energy sources and converting Turkey into a net energy exporter. In 2019, Turkey spent $41.7 billion on imported oil – around 5.5 percent of its GDP – while relying on Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan for a large majority of its energy needs. President Erdoğan emphasized the need to decrease Turkish oil dependence during Ankara’s announcement in August of the discovery of a significant oil field in the Black Sea: “As a country that depended on outside gas for years, we look to the future with more security now … There will be no stopping until we become a net exporter in energy.” Also, according to Turkey’s State-owned Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO), “[o]ur aim in [our offshore exploration] activities is to discover hydrocarbons in our blue homeland and to contribute to reducing our country’s dependence on foreign energy.”

Erdoğan’s declaration marks the logical continuity of a policy that has defined Turkey’s relationship with the Eastern Mediterranean for the past five years. Since 2017, Turkey has acquired a fleet of three drillships and two seismic survey ships that place it in the uppermost echelon of oil-exporting states in the world, rivalling some of the largest private companies in the world in exploration and exploitation capabilities. Turkey’s most recent acquisition, a sixth-generation offshore drilling rig purchased from a Norwegian oil company for $37.5 million, reflects Turkey’s investment in, and optimistic outlook for, the prospect of seabed hydrocarbon extraction in the Eastern Mediterranean.

In addition to acquiring the means for accessing seabed hydrocarbons, Turkey has engaged in increasingly provocative exploratory activities in potentially lucrative oil fields of the Eastern Mediterranean. The Fatih and the Yavuz, two of Turkey’s drillships, have been deployed in disputed waters to the east and south of the island of Cyprus over the past several years, drawing widespread condemnation from regional states and the European Union. Most recently, Turkey sent the seismic vessel Oruç Reis with a naval escort to contested waters west and south of Cyprus, which has resulted in international condemnation and France’s deployment of a frigate and several fighter jets to the region in support of Greece and Cyprus. Grandstanding and posturing by both sides resulted in a recent collision between a Greek and Turkish naval vessel, demonstrating the inherent risk of intentional or inadvertent escalation of tensions resulting from Turkey’s activities and the associated responses by rival claimants.

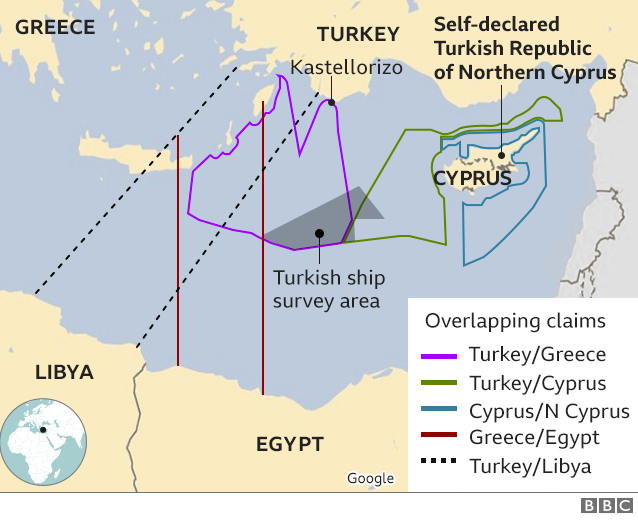

On the diplomatic front, Turkey has entered into a series of agreements that ostensibly sanction its exploratory activities. In 2011, Turkey entered into an agreement with the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” (TRNC) that purports to delimit the continental shelf boundary between Cyprus and Turkey. As a follow-on to that agreement, TPAO signed oil services and production share agreements with the TRNC covering one onshore and seven offshore fields in disputed Cypriot waters. In 2019, Turkey signed a maritime boundary delimitation agreement with the Libyan Government of National Accord that purports to assign to the two nations maritime zones in waters claimed by Greece and Cyprus, which drew criticism from both the European Union and the United States. Since then, Turkey has designated seven license areas in waters covered by the agreement for oil exploration and drilling.

Contemporaneously, Turkey has heightened its military presence in the region through overt demonstrations of its naval and aerial capabilities. Exercise Sea Wolf, held in 2019 to demonstrate the “Turkish Armed Forces’ resolution and capability in protecting the country’s security as well as its rights and interests in the seas,” incorporated over 25,000 personnel and 100 vessels in the Mediterranean, the Aegean, and the Black Sea. Most recently, Turkey announced the commencement of live-fire naval drills in the Mediterranean as a direct response to Greece’s ratification of a maritime accord with Egypt.

Amidst these developments, Turkey maintains a claim to legitimacy in its quest for hydrocarbon resources. “We don’t have our eye on someone else’s territory, sovereignty and interests,” Erdoğan recently announced, “but we will make no concessions on that which is ours … We are determined to do whatever is necessary.”

Legally Problematic and Provocative “Mavi Vatan”

Turkey has advanced two legal justifications for its exploratory activities in the Eastern Mediterranean: that it is doing so pursuant to license granted to it by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), and that its explorations are occurring in waters in which Turkey has sovereign rights, including exclusive ownership of all hydrocarbon resources and the exclusive rights to exploit any such resources. Both of these arguments are legally problematic.

In 1960, Cyprus, formerly a British colony, attained independence through the Zürich and London Agreements between the United Kingdom, Greece, and Turkey. In 1974, in response to sectarian violence between the majority Greek and the minority Turkish populace, and to thwart the threatened unification of the island with Greece, Turkey invaded Cyprus and initiated an occupation of the northern 40 percent of the island that continues today. In 1983, the Turkish-occupied zone declared itself an independent State, the TRNC. However, only Turkey alone recognizes the TRNC’s claim of statehood. The United Nations does not recognize the TRNC, considering it instead as a “legally invalid” secessionist entity of the Republic of Cyprus (UNSCR 541 (1983); UNSCR 550 (1984)). The latter resolution calls on all States to “respect the sovereignty, independence, [and] territorial integrity …. of the Republic of Cyprus (ROC)” as the sole legitimate government of the island.

As a non-state, the TRNC is not competent to declare maritime zones, negotiate international agreements, or purport to grant concessions or any rights in Cypriot waters. Turkey’s reliance on maritime boundary agreements negotiated with the so-called TRNC, and on “grants” or “concessions” by the “TRNC” in maritime zones it invalidly claims, is done not only in defiance of the United Nations Security Council and the global community, but is rightly viewed by the Republic of Cyprus as an assault on its sovereignty. This view is supported and reflected in a joint statement by the Foreign Ministers of Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, France, and the UAE in May 2020 that, among other things, “denounced the ongoing Turkish illegal activities in the Cypriot Exclusive Economic Zone and its territorial waters, as they represent a clear violation of international law as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. It is the sixth attempt by Turkey in less than a year to illegally conduct drilling operations in Cyprus’ maritime zones.”

Outside “TRNC” waters, Turkey has attempted to justify its exploratory activities by claiming that they are conducted in waters in which Turkey has “ipso facto and ab initio legal and sovereign rights,” which translates into an assertion that the exploration is being conducted on Turkey’s continental shelf. According to Article 77 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a state like Turkey (but unlike the TRNC) possesses “exclusive sovereign right for the purpose of exploring and exploiting” the natural resources of its continental shelf, including the “mineral and other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil.”1 Though Turkey is not a state party to UNCLOS, Article 77’s provisions reflect customary international law, and thus both empower but also constrain Turkey’s (and other states’) continental shelf entitlements. Absent unusual subsurface conditions, the maximum breadth of a state’s continental shelf is 200 nautical miles (nm) from its baselines, typically the low-water line of its coast.

When, as is the case here, the continental shelf entitlements of opposite (e.g. Cyprus and Egypt) or adjacent (e.g. Greece and Turkey) states overlap, customary international law (as reflected in UNCLOS Articles 74 and 83) requires states to agree on a boundary delimitation based on international law to reach an “equitable” solution. In the Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt and Cyprus agreed on a maritime boundary delimitation (which Turkey does not recognize) in 2003. As already discussed, Turkey and Libya agreed on a maritime boundary in 2019 (which Greece and Cyprus have protested), and Greece and Egypt delimited their maritime boundary in August 2020 (which Turkey has protested). It is important to note that according to Article 34 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, these bilateral treaties create neither obligations nor rights for a third state without its consent. In other words, these negotiated boundary (and associated resource) delimitations only purport to create rights and obligations for the states that agreed to them.

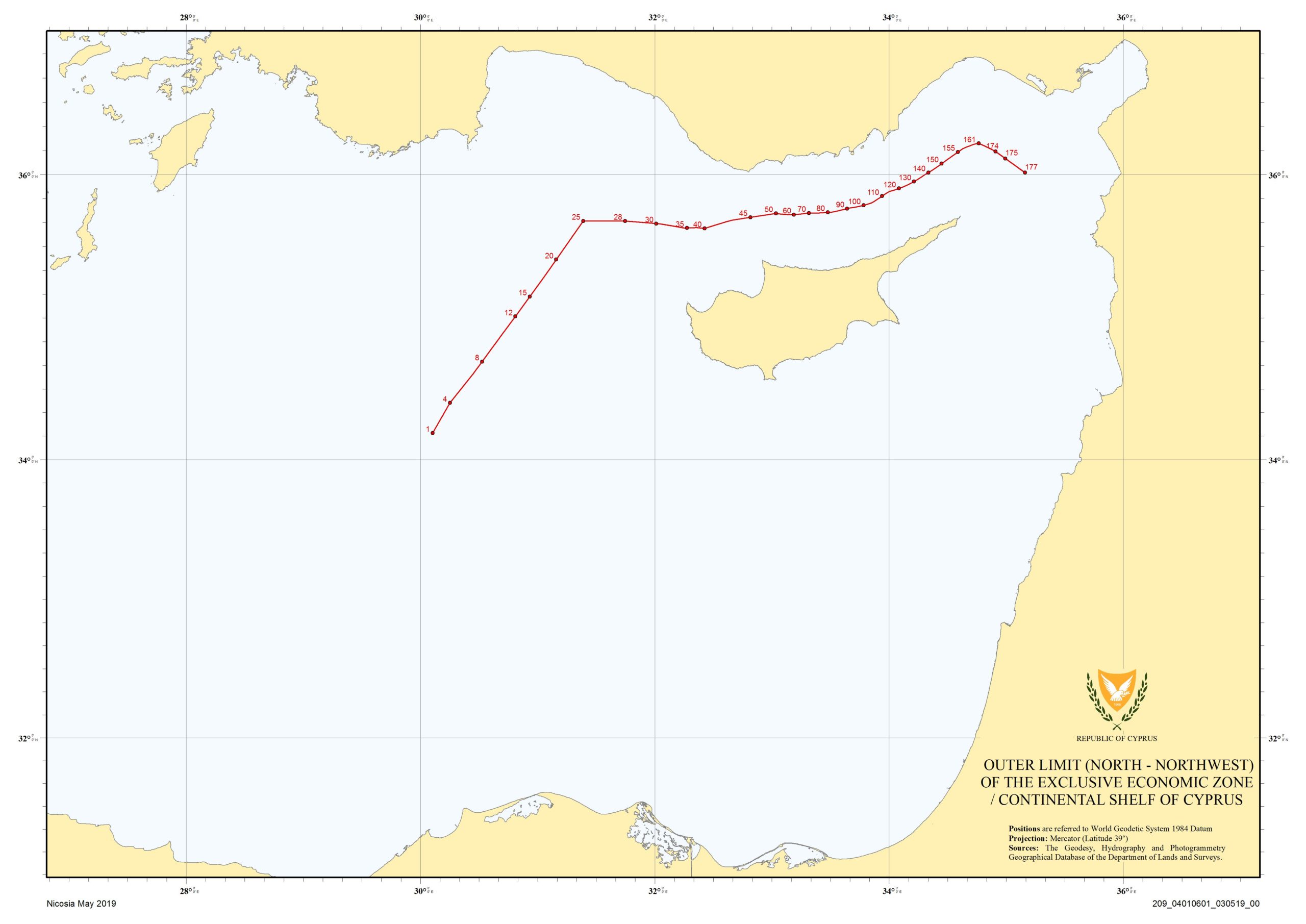

Whether done through a negotiated agreement or through resort to a judicial or arbitral tribunal, the process for determining an “equitable” maritime boundary that has crystallized under both UNCLOS and customary international law begins with the drawing of a provisional equidistance line (the line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the respective states’ baselines). This equidistance line, also referred to as a median line, should be adjusted as equity demands to take into account special or relevant circumstances, such as a marked disproportionality between the length of the parties’ relevant coasts and the maritime areas that appertain to them. All of the maritime boundary delimitation agreements referenced above, plus others that have been negotiated in the region (Cyprus-Lebanon and Cyprus-Israel), have accepted equidistance as the underlying legal doctrine for determining “equity.” Equidistance also seems to be the underlying principle in Turkey’s unilateral declaration of a maritime boundary between itself and Egypt, which Cyprus has protested, and in Cyprus’s unilateral declaration of a continental shelf boundary between it and Turkey, depicted below.

As for Greece and Turkey, Greece in 1976 petitioned the International Court of Justice to delimit its respective continental shelves and Turkey’s. Turkey disputed the court’s jurisdiction, and in a 1978 ruling, the court agreed with Turkey and dismissed the case. The two states have not reached a maritime boundary delimitation agreement since.

The depiction below is of existing claims in the Eastern Mediterranean to the south and west of Cyprus based either on agreement or on unilateral declaration, or of the maritime boundaries that would exist through strict application of the equidistance principle in cases where no specific claims have been made. Superimposed on this depiction is the area of exploration of the Oruç Reis. As can be seen, Turkey’s claim to undisputed “ipso facto and ab initio legal and sovereign rights” in the area being explored is not correct as both Cyprus and Greece have legitimate reasons to claim most or all of the waters and their related resources being surveyed by the Oruç Reis. In fact, as discussed below and in this recent post on the blog of the European Journal of International Law , due to the concavity formed by the coasts of the Dodecanese Islands, Turkey, and Cyprus, Turkey’s maritime entitlement in the waters at issue, without an equitable adjustment, could be as small as the two inverted triangles on either side of Kastellorizo Island (see depiction below). Egypt has also protested Turkey’s most recent exploration activities, claiming that they encroach on areas of Egypt’s continental shelf. All three nations justifiably feel that Turkey is violating international law by its exploratory activities in their waters, which are preliminary activities to Turkey’s ultimate design to, in their view, steal their hydrocarbon resources.

Analysis

Turkey’s exploratory activities in support of Mavi Vatan have occurred in disputed waters – waters in which regional states, often with a long history of antagonistic relations with Turkey, have provisional maritime entitlements superior to those of Turkey. These aggrieved neighbors, and their friends and allies, have strenuously objected through words and deeds to Turkey’s provocative actions. All of this has significantly increased regional insecurity.

The international reaction, both extant and future, presents Turkey with a stark choice and a difficult calculus – is it more likely to get what it wants through continued confrontation and belligerence, or through accommodation? To date, the former course has provoked, among other consequences, the antagonism of powerful regional states like Egypt and Israel; strong condemnations from the EU and the deployment of military hardware to the region from aggrieved EU/NATO nations; the EU’s reduction of its financial aid package to Turkey for 2020 by €145.8 million; U.S. sympathy for the plight of Cyprus in the form of the partial lifting of the 10-year embargo on the sale of military equipment to the island; the warming of the U.S.’s complicated relations with Greece; and Turkey’s exclusion from emerging collaborative enterprises such as the EastMed Gas Forum, comprised of Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and Palestine.

How much Eastern Mediterranean hydrocarbon production or extraction has Turkey engaged in to counterbalance these consequences? None. Nor is it likely to ever get to the production stage in any disputed waters at issue, because the international community is unlikely to permit such a blatant assault on international law, international comity, and the rights and entitlements of weaker states. Finally, as mentioned before, the current escalatory environment brings with it a very real risk of armed conflict, either deliberate or inadvertent, which will benefit no one. For these reasons, continued confrontation and belligerence, though it might play well to a certain domestic audience, does not seem like an attractive or fruitful course.

How about accommodation? All parties with potential entitlements in the disputed waters at issue have expressed a willingness to negotiate, though Turkey’s offer only extends to relevant coastal states “that it recognizes and with which it has diplomatic relations,” which precludes negotiations with the ROC. But Turkey may not have any choice if it wants to depart from the pathway of confrontation and belligerence. None of the concessions purportedly granted to the TPAO by the “TRNC” are likely to ever lead to productive wells and fields, for the reasons discussed above, unless there is an accommodation with Cyprus (specifically, the ROC). To the west of the island, the only way the green line on the east side of the larger inverted triangle representing Turkey’s maritime entitlement in the illustration above can get equitably adjusted to ease the “cutoff effect” of the concave coastlines is through negotiation with Cyprus. Absent such negotiation, Cyprus has no enticement to agree to an adjustment of that line, and the international community will support Cyprus’s position as the legally correct one under the customary international law of the sea.

Ironically, as negotiations with Cyprus necessarily involve recognition of the Republic of Cyprus, these seemingly intractable maritime disputes may prove to be the catalyst for the long-sought but ever-elusive “grand bargain” involving Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey. In return for some maritime concessions plus a seat at the table at the EastMed Gas Forum or similar energy extraction or distribution consortia, perhaps Turkey could be enticed both to resolve the “Cyprus problem” and to reach equitable maritime boundary delimitations with Greece. Such a hope could very well prove to be chimeric; numerous prior attempts at reconciliation have begun with giddy expectations but ended in impasse and frustration. But for Turkey to realize its “blue homeland” aspirations, there really appears to be no attractive alternative. The recent discovery by Turkey of significant hydrocarbon deposits in its Black Sea waters, alluded to earlier, may provide Turkey with some space to back off of some of its bellicose and uncompromising pronouncements regarding accommodation in the Eastern Mediterranean as a policy option.

Conclusion

Turkey’s “Mavi Vatan” strategy in the Eastern Mediterranean is beset with difficulties. Neither geography nor the law are kind to Turkey, leaving it, in the absence of equitable boundary adjustments, with limited waters in which it can legitimately claim sovereign rights over the related hydrocarbon resources. Its efforts to belligerently assert rights in contravention of the law and in defiance of the international community have only succeeded in portraying Turkey as an international pariah, elicited a chorus of condemnation, and solidified support, both verbal and material, for rival claimants. It has also left Turkey on the outside looking in with respect to developing regional cooperative energy ventures. Though militarily powerful, Turkey is not sufficiently strong to impose its will through the threat or use of force. This is especially true since there is a strong likelihood – or at least a sufficient likelihood so that Turkey can’t lightly ignore it – that powerful regional or EU nations may go to the assistance of Greece or Cyprus in response to Turkey’s use or threatened use of armed force.

Turkey’s options in pursuit of its “Mavi Vatan” strategy in the Eastern Mediterranean appear to be to remain belligerent and defiant, which will get it nothing but further isolation and ostracism, or to pursue a compromise, which would get it some, but not all, of what it would like. As a further complication, Turkey’s stance toward the ROC would have to change in order to pursue the compromise option, which, in addition to the maritime boundary compromise itself, would be a bitter domestic pill for the Erdoğan government to swallow. However, the recent discovery of what has been billed as significant Black Sea hydrocarbon reserves may allay what might otherwise be viewed as a retreat in the Eastern Mediterranean; and beyond its political usefulness, may prove to be a viable alternative, in whole or in part, to the Eastern Mediterranean as a means of pursuing “Mavi Vatan.”

Andrew Norris is a retired U.S. Coast Guard Captain and holds a Juris Doctorate. His last assignment in the Coast Guard was as the Robert J. Papp, Jr. Professor of Maritime Security at the U.S. Naval War College. He currently works as a maritime legal and regulatory consultant. He may be reached at [email protected].

Alexander Norris is a third-year undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania currently pursuing a double-major in international relations and diplomatic history, with minors in both Middle Eastern Studies and Hispanic Studies. He published an article titled, “One Island, Two Cypruses: A Realist Examination of Turkey’s Recent Actions in the Eastern Mediterranean,” in the Spring 2020 SIR Journal of International Relations, and is an editor for the University of Pennsylvania’s premier journal on Middle Eastern affairs. He may be reached at [email protected].

*Editor’s Note: This statement was originally attributed to Prime Minister Erdogan, when it was spoken by Commander Ağmış.

1. Per UNCLOS Article 56, a State possesses the exact same entitlements in its declared Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as it does in its continental shelf. Also, like the continental shelf, the maximum EEZ breadth is 200 nautical miles from its baseline. The terms “EEZ” and “continental shelf” can thus be used interchangeably to describe the source of a State’s entitlement to sovereign rights over subsurface hydrocarbon resources.

Featured Image: The Turkish vessel Oruc Reis is escorted into Greek waters midway between Crete and Cyprus by five Turkish Navy vessels on Monday, August 10, 2020. (Photo via Turkish Defense Ministry)

President Erdogan is relying on the “Might Makes Right” strategy. The division of territorial waters by treaty favors Greece. As the author points out in his excellent article, Turkey wants/needs to be energy independent and to do so needs to find and claim oil in the Aegean Sea. As the author correctly points out, the law by treaty is not in Turkey’s favor, so Erdogan is left with several choices. Everyone agrees to let Turkey have the oil, the International agencies and courts reverse positions or Turkey “muscles its way in” and accepts some kind of “final arbitration” that allows them access to the oil to avoid a war/conflict. Guess which solution Erdogan has taken. Erdogan can not afford to accept anything less than some deal where Turkey gets access to the oil, he’s already bet billions on this gamble. It’s a matter of long term strategic needs which makes it vital in Erdogan’s view. He will not back down.

Recommended correction: the Eastern Med has rich reserves of gas, not oil. Likewise, Turkey’s recent find in the Black Sea is a gas field, not an oil field. Oil is not the focus here, and that distinction is meaningful for the infrastructure development and international cooperation required to develop the resource base.

Not mentioning some psycho-anthropological and sociological variables does not diminish the objectivity and the serious scientific geo-political and especially juridictional analysis of the article. However, it seems important for the reader to try to understand some reasons of the “why”

as much as its perspectives.

It’s not about energy (or accessibility to) : as it is well- known Turkey has more hydrocarbon than enough in the Black Sea. Erdoghan’s aggressive policy, in the Mediterranean first, emanates from his permanent frustration, as an islamist activist of the Muslims Brotherhood organization, at seeing his will to spread at all costs the Islamist political system, to start to be better and better known and consequently, thwarted by some of the same ones who encouraged him. It’s not any more about ideas but about the intensity of the violence which is used to set them everywhere, anytime, anyhow, especially in “ dar al harb”.

As he constantly demonstrates, he created this conflict too ( among others ) as usual (1) in order to justify his new aggression and invasion – what’s more by retroactive effect as regards Cyprus occupied and divided for almost 50 years by his country, as the authors rightly mentioned.

“Mavi vatan” ( ie, The nation water) is not an isolated concept but an element of a political set in which the strategy of ( the old ) global Islamist expansion ( Fath ) ( othomanism was a continuation ) with a jihadist character and basic method going beyond the confined circle of the Mediterranean constitutes a fundamental pillar (2).

In Erdoghan’s perception, the “ Mavi vatan” it’s not for Turkey only but for the whole world – like the Mahdy or the Wahabism, his brothers – rivals.

Combined with the cult of the personality, it’s applied with a subtle but nevertheless through a clear game; this imperialist strategy takes on a character which tends to become very dangerous and not only a “Disruptive” para-phenomenon ( 2). Like any dictator, he could end up the classical way : blinded by his own image ( fake grandeur / megalomania ) and encouraged by the lack of a serious opposition ( interior) and sustained answer – counter offensive ( exterior) ( 3) his strategy of rushing/ escape forward will backfire severely. In reality, the aggressivity of Erdoghan is proportional to his feeling that his regime and method of governing are becoming more and more a source of serious troubles and deep destructive problems, for him first. And at the same time he thinks he can handle international relations as he does at home, otherwise, he loses his “credibility”; hence his cyclic bidding tactic.

As the article specifies, the law is not on his side, on the contrary. But if this precision is argued and supported by various conventions, agreements, etc., its approach remains timid; would it be, perhaps, to avoid certain sensitivities especially nowadays and unfortunately in some American educational institutions too ( 4) ?

Because, one must not forget that during WWI and WWII, Turkey was among the aggressors and among the principal enemies (5); and lost them. Reason why – and this is the least – these treaties should not be ( and are not ) “favorable” to him.

The contrary would be illogical and abnormal. Let’s only add that Turkey never paid reparations for her several crimes as the Armenian genocide.

During the “ Cold War”, through – and thanks to – NATO and America, Turkey defended herself first, from the “ neighbour “, the soviet communist imperialism, more than she defends the West. The latter must not have any sort of complex towards her : she owns the West in general and America in particular by far more than they own her. The more the free societies inclines to bow, the more dictators as Erdoghan go on in aggressiveness, vulgarity and violence.

It’s not about energy : the credibility of the continuation of NATO and EU, as free societies and effective institutions, is at sake. The seriousness of the situation no longer authorizes declarative behavior. EU cannot, on the one hand, continue their “French-English leave” tactic , hidden behind a form on “diplomacy”, and on the other hand by consequence, allow themselves to blame ( and for some to hate ) America and Pr. Trump, when for example, he dared mention their responsibility to participate fairly ( they have the capacity, if it’s not more than America in relative value ) in sharing the common burden – which is not only financial – of the collective defense of our common values and fundamental liberties.

* * *

( 1) Just to mention “Mavi Marmra” invasion against Israel. ( infra **).

( 2) For example : the name given to its explorer ships; the reislamization of the Turkish society, system, churchs; permanent threat on the Jewish community, support for Islamist and terrorist movements ,etc.

( 2) F22, SS400, perpetual attacks against : the Kurds, Israel, Greece, continental Europe through islamists “migrants”; infiltration -islamisation of Africa hand in hand with his associate- rival, the ayatollahs in Iran which escapes from the sanctions by exporting oil through Syria and Turkey, etc.

( 3) Examples ? What France did till nowadays is a military half-way step ( the classical gradual response );

Germany ? It’s the first investor in Turkey, she talks only. Facing Putin in the Baltic ? Germany is present through 2 tanks.

GB ? Forgets about Cyprus, lost in Brexit, and as the rest, dreams about Iran’s bazar and none care about its “bomb” !

(4) As for Erdoghan, his “researchers” and media, they practise no restraint. Reciprocity is not at the “rendez-vous”.

( 5) WWI : Armenian genocide and all other atrocities; WWII : huge materials of the industrial military equipments of the Nazis were produced in Turkey; oil and other goods were moving through this country for the Axis Forces to support the war effort against the Allies; etc…

NOTES :

* US embargo of Cyprus was for 33 years and not 10.

** « Palestine » doesn’t exist and has never existed as a state nor a country. The arabised people living on some Jewish lands in Judea are governed by an autonomous authority called “ Arab Palestinian Authority” ( the others in Gaza are under the partners associates of the PA : Hamas and Islamic Jihad , terrorist groups backed by Erdoghan – among others ) ( supra 1).